A temporary victory for abortion pills, the effective legalization of machine guns, and lower court protection for families with trans children. Meanwhile, continued stalling to protect Donald Trump from prosecution.

We’re getting near the end of the Supreme Court’s term, so the rulings will come hot and heavy for the rest of the month. Several important cases are still pending, but a few decisions came in this week.

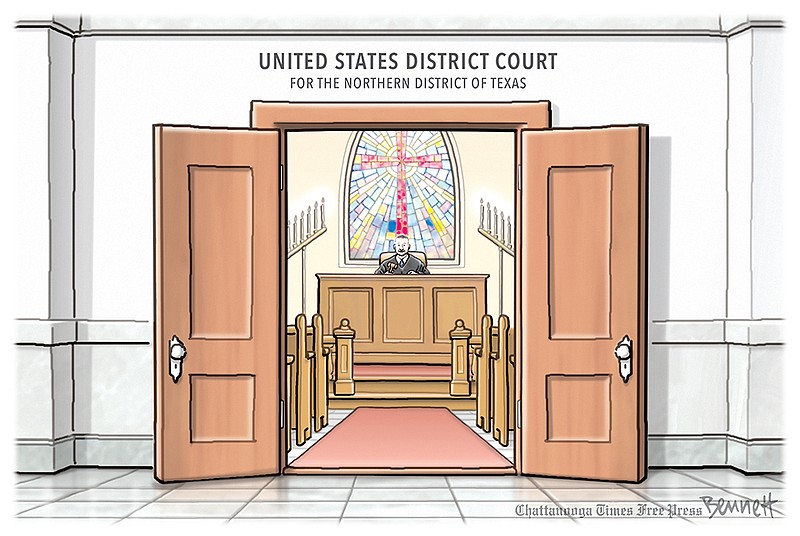

The abortion pill mifepristone got a reprieve. As I’ve explained in the past, there is a federal district around Amarillo where cases are wired to go in front of a Christian nationalist judge, Matthew Kacsmaryk, and go from there to the nation’s most conservative appeals court, the Fifth. In the spring of 2023, anti-abortion groups (established in Amarillo precisely to take advantage of this legal pipeline) targeted mifepristone, the drug used in more than half of abortions nationally.

Predictably, Kacsmaryk suspended the FDA’s approval of mifepristone, effectively banning it nationally. That decision was partially reversed by the Fifth Circuit, and then totally stayed by the Supreme Court, pending its own decision. (So far, no one has been prevented from using mifepristone in states where it would otherwise be permitted.)

There are many ways to reverse Kacsmaryk’s decision, because it is baseless both legally and scientifically. Vox described the scientific situation like this:

The case has virtually no scientific merit, and challenging the use of a drug that has been studied and safely used for over two decades is highly unusual. Jack Resneck Jr., the president of the American Medical Association, said in a statement Friday night that Kacsmaryk’s “disregard for well-established scientific facts in favor of speculative allegations and ideological assertions will cause harm to our patients and undermines the health of the nation.”

But the Court decided not to go there. Instead, it pointed to the legal ridiculousness of the lawsuit: The plaintiffs have no standing to sue. [1]

As was obvious from the beginning, these plaintiffs — primarily doctors who don’t prescribe mifepristone — have no standing. They made up, and two levels of federal courts accepted, a ridiculous explanation of how mifepristone harms them: On the rare occasions when mifepristone fails, a woman caught in the middle of a miscarriage might show up on their doorsteps or emergency rooms, and they might have to do a procedure they morally object to in order to save her life.

Putting aside the issue of how any principle requiring a doctor to do nothing while he watches a woman die can be considered “moral”, Justice Kavanaugh (writing for a rare 9-0 Court) noted that federal conscience protections already protect the doctors, so they are not injured. So the suit should never have been heard in the first place. Slate’s Dahlia Lithwich and Mark Joseph Stern comment:

A doctor who opposes abortion, the court affirmed, may stand by and watch a patient bleed out rather than treat her in contravention of his conscience. Ironically, then, an anti-abortion statute that protects anti-abortion doctors played a key role in defeating the plaintiffs’ claim. Their own lavish safeguards against terminating a pregnancy—or even just treating a patient who already terminated a pregnancy—helped defeat their attempt to pull mifepristone off the market.

They go on to observe:

Yet the decision was not a total defeat for anti-abortion activists. Among other things, Kavanaugh slipped language into his opinion that could expand protections for physicians who refuse to provide emergency abortions, potentially imperiling the lives of patients.

The Court’s ruling also left open the fundamental issue — whether the FDA was right (or within its legal authority) to approve mifepristone at all. The most likely course forward from here is that new plaintiffs with different explanations of why they are not busybodies will pick up the suit, and the whole circus will start again.

One path flows from a brief line near the end of the Alliance opinion: “[I]t is not clear that no one else would have standing to challenge FDA’s relaxed regulation of mifepristone.” Last January, Kacsmaryk ruled that three red states — Idaho, Missouri, and Kansas — could join this lawsuit and press the claim that mifepristone should be banned.

It is far from clear how these states are injured by the mere fact that mifepristone is legal. But Kacsmaryk’s (and the Fifth Circuit’s) behavior in this case and others shows that he’s willing to bend the law into pretzels in order to rule against abortion rights. It is likely, in other words, that Kacsmaryk will simply make up some reason why the red states have standing to sue and then issue a new order attempting to ban mifepristone.

In other words, this isn’t over. Another path forward is that Trump could win the election and instruct the FDA to rescind its approval or impose new restrictions on mifepristone’s use, or reinterpret the Comstock Act of 1873 to prevent distribution of mifepristone by mail. Good luck getting a straight answer out of him on those questions.

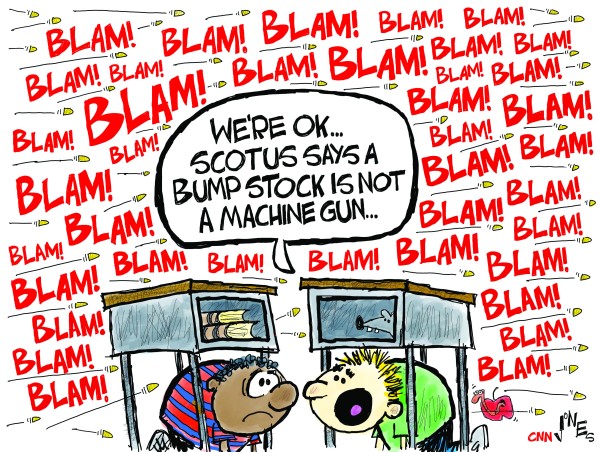

It’s now legal to alter your AR-15 to function as a machine gun. If you’ve ever watched a gangster movie set in the Al Capone era, you’ve seen the destructive power of that era’s submachine guns, the weapon of choice in the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre of 1929.

Responding to that problem, Congress made tommy guns and other fully automatic weapons illegal for civilian use in the National Firearms Act of 1934. By 2002, though, a new technology had inserted a loophole in that ban: the bump stock. A bump stock is an add-on piece of equipment that uses a semiautomatic rifle’s recoil to release and pull the trigger over and over again, so that the shooter’s experience resembles firing a machine gun.

Most explanations of bump stocks available on the internet are by pro- or anti-gun activists, and so should be taken with a grain of salt. However, this one comes from a general how-things-work channel, Zack Nelson’s JerryRigEverything. The video was made while bump stocks were legal.

Zack refuses to state an opinion on whether bump stocks should be legal or not, saying ambiguously: “Personally, I think guns are a great hobby, but not everyone in the world is sane.”

Most people had never heard of bump stocks until the Las Vegas massacre of 2017, when a gunman used one to fire more than 1,000 rounds down on a crowd gathered for a music festival. He killed 60 and wounded over 400, with an almost equal number injured in the stampede of people trying to get to safety. (Like tommy guns, bump-stocked AR-15s aren’t very accurate, making them poor sniper weapons. But if you’re firing at thousands of people, accuracy isn’t that important.) To the untrained ear, audio from the massacre certainly sounds like somebody is firing a fully automatic weapon. (For what it’s worth, real gun people claim otherwise, that a fully automatic machine gun fires even faster.)

Responding to public outrage, the Trump administration Bureau of Alcohol Tobacco and Firearms (ATF) changed its interpretation of the NFA’s machine gun ban, ruling that a bump stock converted a semiautomatic weapon into an automatic weapon, and so was illegal. That ruling was challenged in court, and the case has taken six years to make it to the Supreme Court.

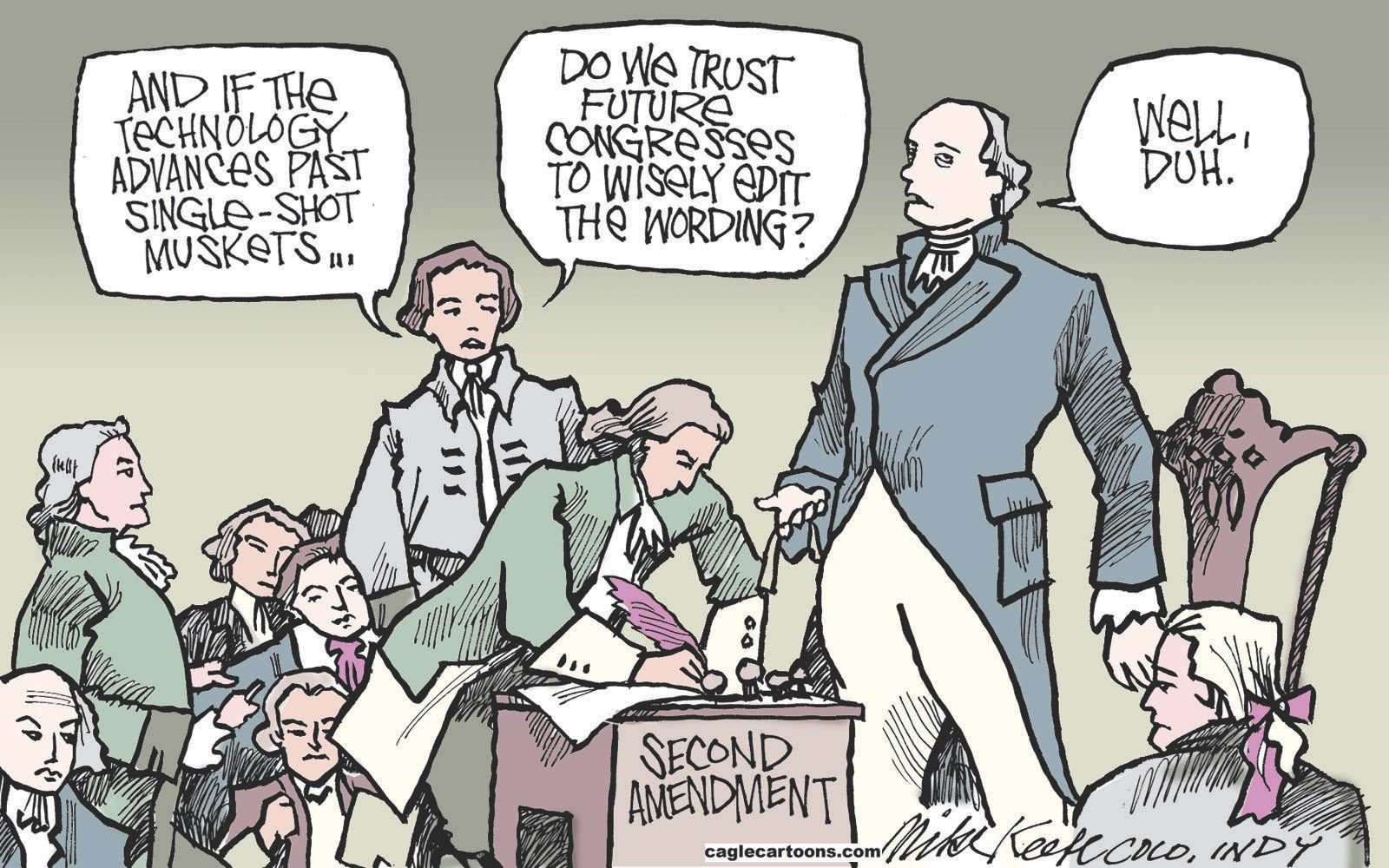

Friday, the Court struck down the bump stock ban in a ruling that split 6-3 along the usual ideological divide. The majority opinion was written by the corrupt Justice Clarence Thomas [2]. It centers on the exact definition of “machinegun” in the NFA:

any weapon which shoots, is designed to shoot, or can be readily restored to shoot, automatically more than one shot, without manual reloading, by a single function of the trigger.

Thomas goes on to focus on the “function of the trigger” in its mechanical sense: As far as the gun is concerned, its trigger is being pulled once for each shot. In her dissent, Justice Sonya Sotomayor focuses on the experience of the shooter, who pulls the trigger once and keeps his finger stationary as the gun bucks back and forth against it. The Congress of 1934, I suspect, intended to focus on the experience of the victims, but they didn’t phrase the law that way, so here we are.

In an ideal world, it’s obvious what would happen next: Congress would say “oops” and would amend the NFA based on some other criteria, like perhaps the rate of fire. That’s what President Biden wants [3], and what Justice Alito’s concurrence suggests, perhaps disingenuously.

There is a simple remedy for the disparate treatment of bump stocks and machineguns. Congress can amend the law—and perhaps would have done so already if ATF had stuck with its earlier interpretation. Now that the situation is clear, Congress can act.

The reason I suggest Alito’s recommendation might not be completely serious is that he knows his right-wing allies won’t allow this to happen. I would be amazed if Speaker Johnson allowed even the narrowest possible bump-stock ban to make it to the House floor for a vote, and Republicans would almost certainly filibuster such a bill in the Senate.

Sunday, possible Trump VP Senator Tim Scott dodged taking any position on a bump stock ban, while another Trump VP hopeful from the House, Byron Donalds went full gaslight:

A bump stock does not cause anybody to be shot in the United States. That is the shooter that does that.

Donalds might want to explain that to the families of the Las victims, many of whom would probably be alive if the shooter had not been able to use a bump stock. It’s also worth pointing out that Donalds’ logic justifies legalizing any weapon, no matter how destructive. After all, nuclear weapons don’t destroy cities, people destroy cities.

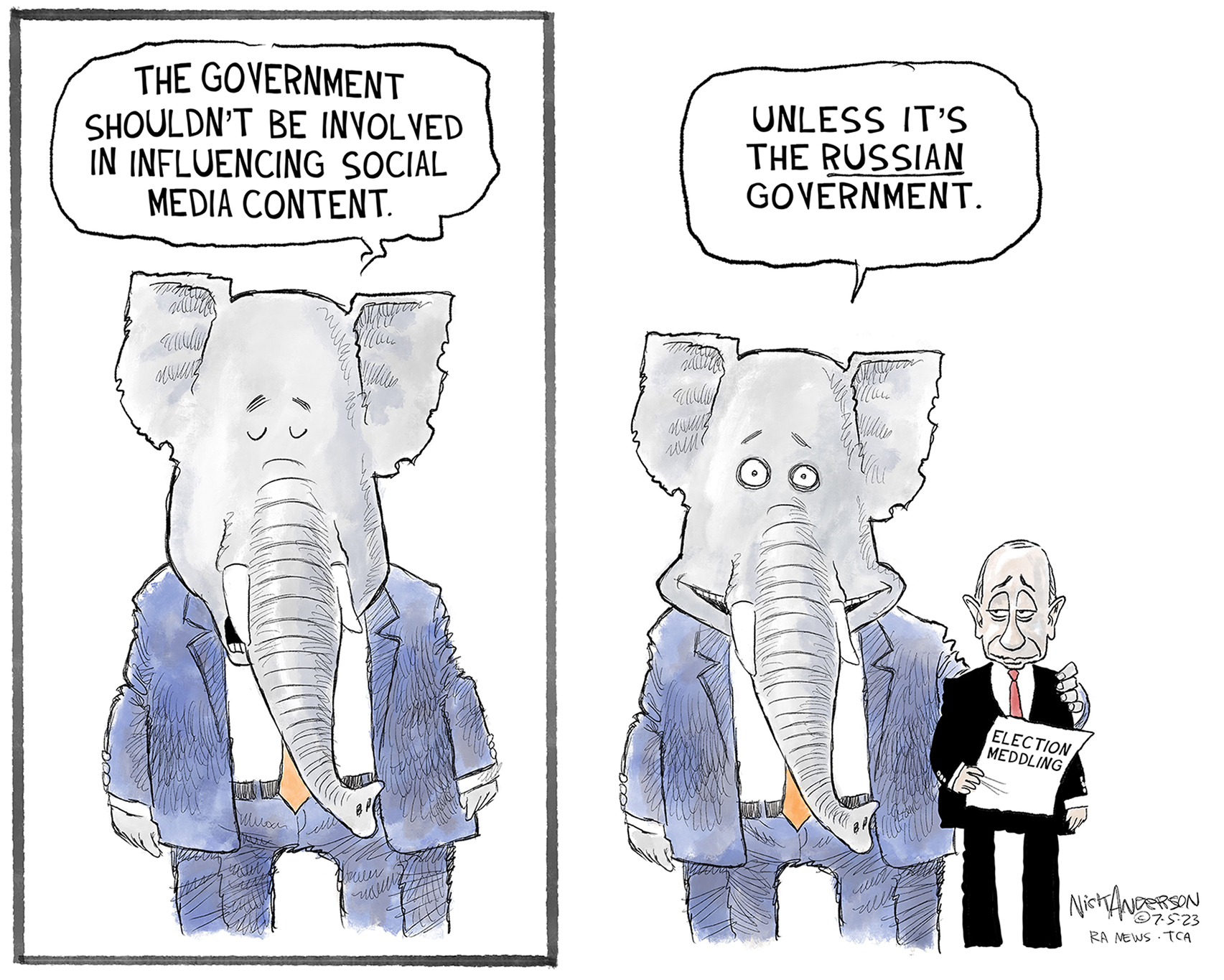

Meanwhile, a spokesman for the Republican Party’s lord and savior, convicted felon Donald Trump, for once expressed faith in our justice system.

The court has spoken and their decision should be respected.

This pattern is not a coincidence: If you make Congress dysfunctional and unresponsive to the people, and then interpret the laws and the powers of agencies like the ATF strictly, the result is that when technology changes, old regulations lapse and can’t be updated. That’s not some unfortunate bit of happenstance; it’s two sides of the same strategy. Today it results in the effective legalization of machine guns. Tomorrow the loophole will be in the Clean Air Act or the antitrust rules. When the laws stand still, malefactors adapt.

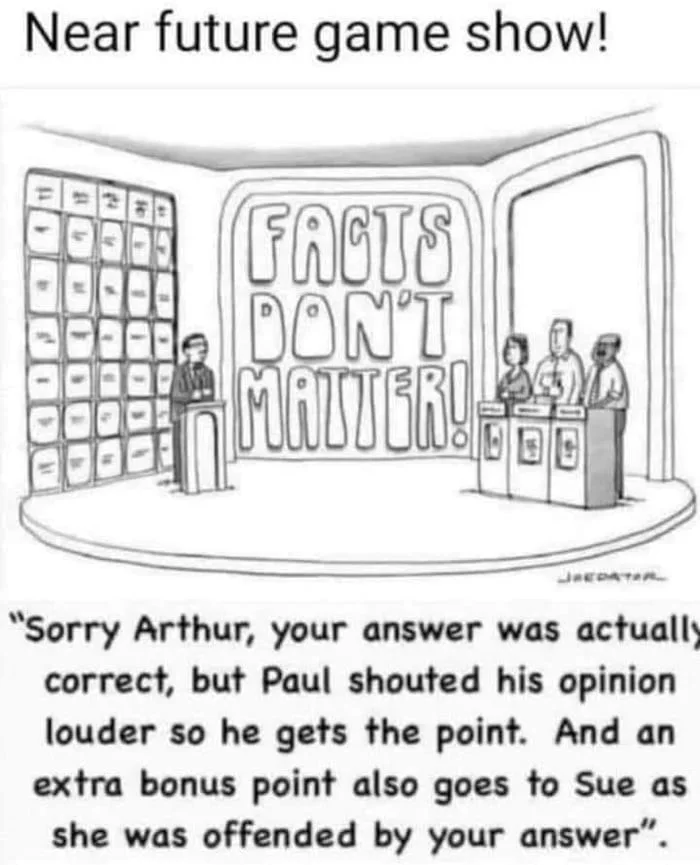

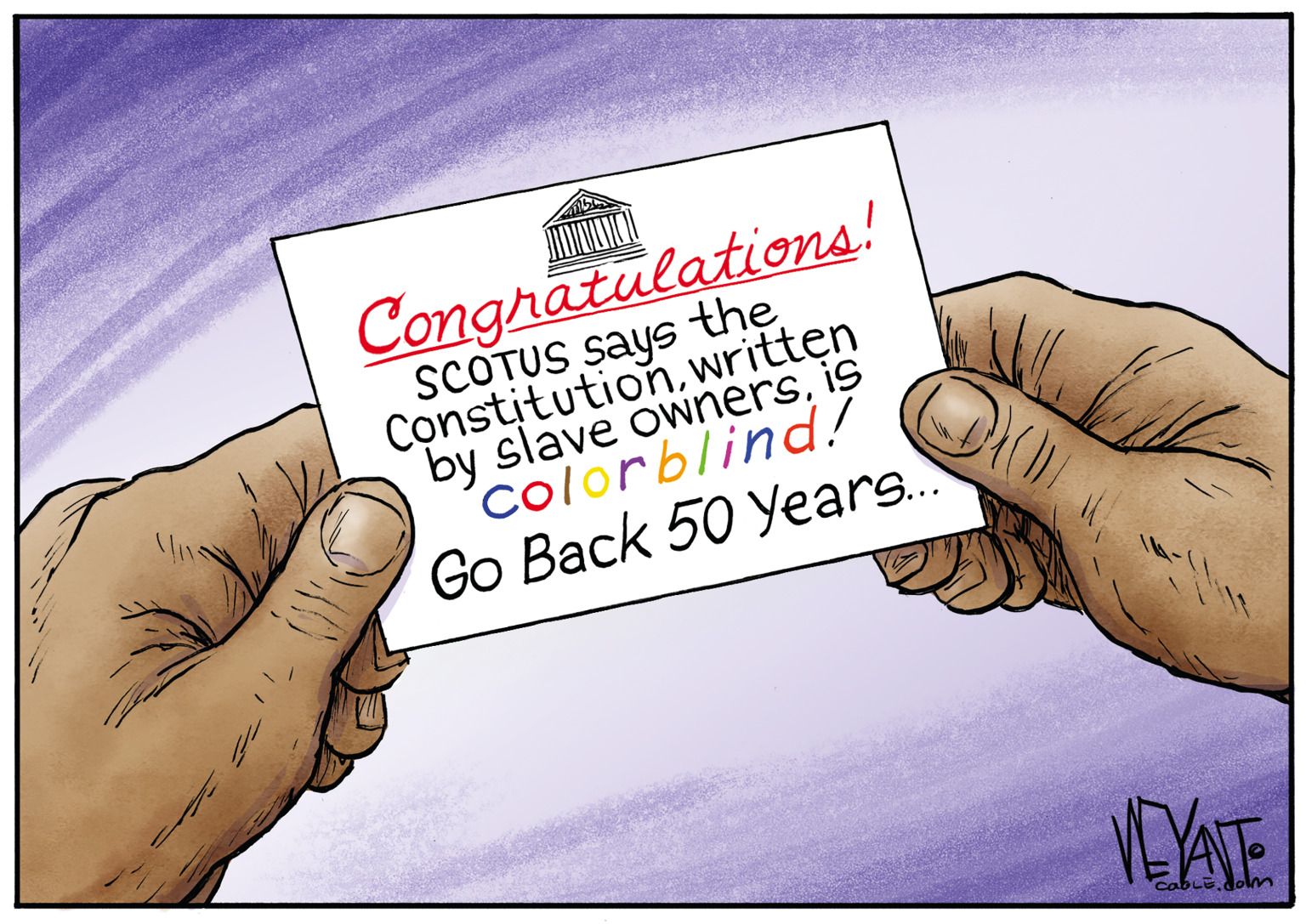

Gender-affirming care. In an important lower-court case, a judge found a Florida law banning gender-affirming care for minors to be unconstitutional. This ruling differs from the case of a similar Alabama law, which was upheld by the 11th Circuit appeals court (where this case is headed) in that Judge Robert Hinkle found malice on the part of the legislature. That issue wasn’t raised in the Alabama case.

The plaintiffs have shown that animus motivated a sufficient number of statutory decisionmakers.

Judge Hinkle found that “gender identity is real” and is distinct from an individual’s “external sexual characteristics and chromosomes”. He also noted that the treatments at issue — puberty blockers and hormones like estrogen and testosterone [4] — are legal in Florida for other purposes.

[C]onsider a child that a physician wishes to treat with GnRH agonists to delay the onset of puberty. Is the treatment legal or illegal? To know the answer, one must know whether the child is cisgender or transgender. The treatment is legal if the child is cisgender but illegal if the child is transgender, because the statute prohibits GnRH agonists only for transgender children, not for anyone else.

If these treatments have risks, parents of non-trans kids (in consultation with doctors) are allowed to judge those risks for themselves. But in trans cases, the state’s judgment prevails.

Susan Doe, Gavin Goe, and Mr. Hamel have obtained appropriate medical care. Qualified professionals have properly evaluated their medical conditions and needs in accordance with the well-established standards of care. The minors, to the extent of their limited ability, and their parents, and Mr. Hamel, all in consultation with the treating professionals, have determined that the benefits of their gender-affirming care will outweigh the risks. The parents’ and Mr. Hamel’s ability to evaluate the benefits and risks of this treatment in their individual circumstances far exceeds the ability of the State of Florida to do so.

Judge Hinkle found a motive for the State of Florida assuming the power to overrule parental and medical judgment:

The defendants [i.e., the State of Florida] have explicitly admitted that prohibiting or impeding individuals from pursuing their transgender identities is not a legitimate state interest. But the record shows beyond any doubt that a significant number of legislators and others involved in the adoption of the statute and rules at issue pursued this admittedly illegitimate interest.

The ruling quotes numerous statements by legislators or Governor DeSantis that show animus, such as referring to transgender witnesses at hearings as “mutants” and “demons”, denying the reality of gender identity, or exaggerating gender-affirming care by talking about “castrating” young boys. The fact that no one supporting the anti-care bill contested these statements, according to the judge, was evidence that such sentiments were widespread in the legislature.

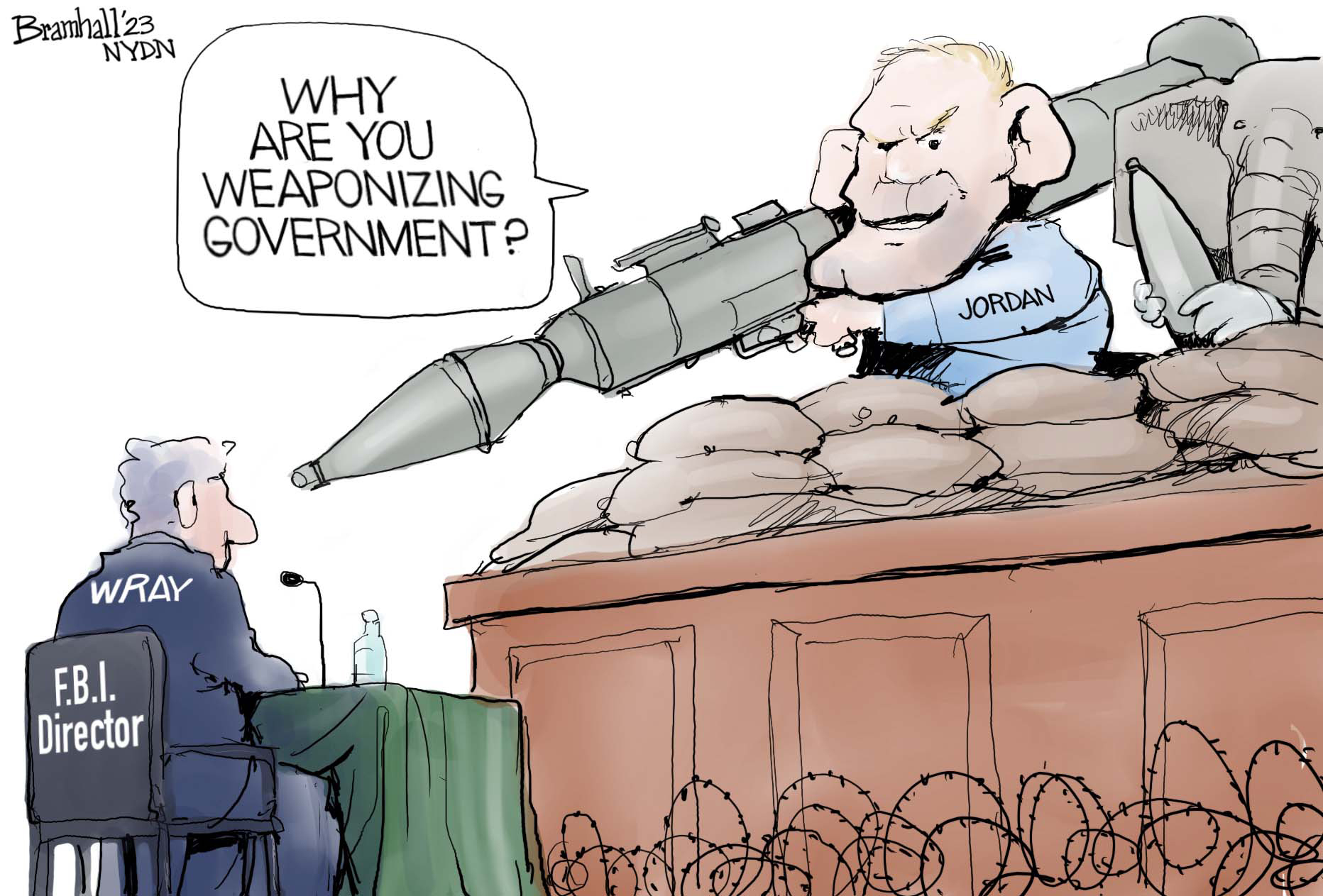

Trump’s immunity. The Court continues to sit on the apparently simple issue of Donald Trump’s absolute-immunity claim, which has been rejected by every lower-court judge who heard it. By taking the case and refusing to rule promptly, the Court has made it all-but-certain that no trial can be held prior to the election on Trump’s plot to stay in power after losing in 2020. Without the Court’s interference, the public would already have heard testimony under oath from key witnesses like Mike Pence and Mark Meadows.

Particularly given the apparent bias of Justices Alito (whose home and vacation home were the site for pro-insurrection flags) and Thomas (whose wife traded texts with Mark Meadows to encourage resistance to accepting the will of the voters), it’s hard to see the Court’s actions as anything other than an attempt to put its thumb on the scale to Trump’s benefit.

My prediction is that the immunity ruling will come out on the second-to-last day of the term. Putting it last would underline the Court’s intent to delay justice, so the conservative majority will probably sacrifice a day or two of delay to avoid that poor appearance.

[1] Standing is one of the basic concepts of civil lawsuits: A court can only rule on a situation if a suit is brought by someone actually affected. For example, I can’t sue for divorce on behalf of one of my friends, no matter how convinced I am that she needs to be out of that marriage. Requiring that a plaintiff have standing is basically a no-busybodies rule.

[2] I am going to use the word corrupt whenever Thomas’ name comes up until he is either removed from the Court or is called to account in some other way. This week we found out that Thomas has received even more billionaire gifts than the $4 million that were previously known.

Thomas claims these gifts are not bribes, but fall into a loophole for gifts from “friends”. However, Thomas’ rich friends are right-wing donors he had never met before joining the Court.

So as far as this blog is concerned, “corrupt Justice Clarence Thomas” is his full name.

[3] Biden would also like to see an assault weapon ban in that amended bill, but is likely to sign a smaller reform if he gets the chance.

[4] Gender-affirming surgeries on minors, according to the judge, “are extraordinarily rare and are not involved in this litigation.”