A summary of his arguments, and how they might be used to take away other constitutional rights.

A week ago, Politico released a leaked draft of Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito’s opinion overturning Roe v Wade. Politico claimed this was to be the majority opinion, representing not just Alito, but supported by Justices Thomas, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Barrett as well. The draft dates from February, and we do not know what revisions may have been made since. The decision on the case (Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health) is expected to be released before the Court’s current term ends in June.

The case concerns a Mississippi law that bans abortions after 15 weeks, in violation of the existing Supreme Court precedents. The Court has three basic options:

- Respect the Roe and Casey precedents by invalidating the Mississippi law.

- Create a loophole that allows the law to take effect, and chips away at abortion rights in general, but does not overturn Roe in its entirety.

- Overturn Roe, allowing states to regulate or ban abortions as they see fit.

This is how I summarized the situation in March:

So it’s clear which approach Roberts will favor: Don’t make headlines by reversing Roe, but chew away at it by creating a loophole for Mississippi, maybe by changing the definition of “viability”. The language of such a decision could subtly invite states to push the boundary further, until a woman’s right to control her own pregnancy would have little practical meaning. Roe would continue to stand, but like a bombed-out building without walls or a roof, would protect no one.

That probably won’t happen, though, for a simple reason: When Barrett replaced Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Roberts lost control of the Court. He is no longer the swing vote, so he loses 5-4 decisions when he sides with the Court’s three surviving liberals.

And I warned that reversing Roe would not be the final chapter of this saga.

Roe doesn’t stand alone. It is part of a web of substantive due process decisions on a variety of issues. Reversing Roe will send ripples through the whole web, putting all those rights up for grabs.

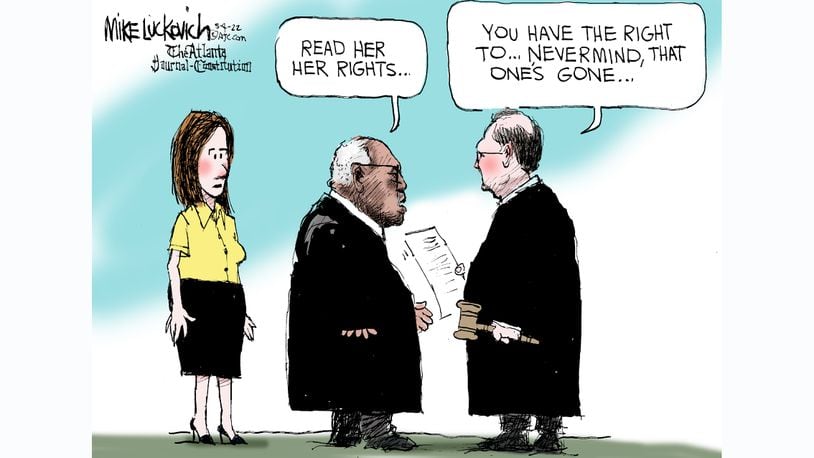

So here we are. Unless something inside the Court has drastically changed since February, the constitutional right to abortion, which has existed for 49 years, will vanish sometime in June, and a number of other rights will be in doubt, including the right to use birth control, for consenting adults to choose their own sexual practices, and for two people of any race or gender to marry.

What does Alito’s ruling do? Alito has written an unambiguous reversal of Roe.

We hold that Roe and Casey must be overruled. The Constitution makes no reference to abortion, and no such right is implicitly protected by any constitutional provision. … Roe was egregiously wrong from the start. Its reasoning was exceptionally weak, and the decision has had damaging consequences.

Unenumerated rights. No one claims that the word “abortion” appears in the Constitution. But there are several places where a judge might find implicit protection for rights not specifically listed:

- The Ninth Amendment, which says “The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.” This recognizes the existence of rights beyond those the Constitution mentions, but provides little basis for identifying them.

- The Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment, which guarantees “any person” within the jurisdiction of the states “the equal protection of the laws”. Judges at many levels have, for example, rooted same-sex marriage here — same-sex couples are guaranteed the equal protection of the marriage laws — but Justice Kennedy’s majority opinion in Obergefell gave equal protection a secondary role.

- The Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment, which says that no one can be deprived of “liberty” without due process of law. Abortion and the related privacy rights have been rooted here, in a doctrine called “substantive due process”, which I described in March.

Another place to look for an unenumerated right is in Supreme Court precedents themselves. Under the doctrine of stare decisis, the Court will usually stand by a previous decision, even if the current justices believe the case was wrongly decided. For example, corporate personhood arises from a bad decision the Court made in 1886. It continues to be upheld despite the fact that the word “corporation” does not appear in the Constitution.

His arguments. Alito dismisses the equal-protection option like this:

[I]t is squarely foreclosed by our precedents, which establish that a State’s regulation of abortion is not a sex-based classification and is thus not subject to the “heightened scrutiny” that applies to such classifications. The regulation of a medical procedure that only one sex can undergo does not trigger heightened constitutional scrutiny unless the regulation is a “mere pretext designed to effect an invidious discrimination against one sex or the other.”

Due-process rights not otherwise mentioned in the Constitution, Alito writes, have to pass what is called the Glucksberg Test:

[T]he Court has long asked whether the right is “deeply rooted in [our] history and tradition” and whether it is essential to our Nation’s “scheme of ordered Liberty.”

He concludes that the right to abortion does not pass this test.

Until the latter part of the 20th century, there was no support in American law for a constitutional right to obtain an abortion. Zero. None. No state constitutional provision had recognized such a right. Until a few years before Roe was handed down, no federal or state court had recognized such a right. Nor had any scholarly treatise of which we are aware. …

Not only was there no support for such a constitutional right until shortly before Roe, but abortion had long been a crime in every single State.

Much of the opinion’s 98 pages consists of a long history lesson about state laws and common law cases.

Alito also addresses the possibility that a right to abortion is part of a broader right to privacy, which does pass Glucksberg.

Casey described it as the freedom to make “intimate and personal choices” that are “central to personal dignity and autonomy”. Casey elaborated: “At the heart of liberty is the right to define one’s own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life.”

Alito also dismisses this justification in what is by far the weakest part of his argument, consisting mostly (in my opinion) of question-begging and because-I-said-so.

Our nation’s historical understanding of ordered liberty does not prevent the people’s elected representatives from deciding how abortion should be regulated. … This attempts to justify abortion through appeals to a broader right to autonomy and to define one’s “concept of existence” prove too much. Those criteria, at a high level of generality, could license fundamental rights to illicit drug use, prostitution, and the like.

What sharply distinguishes the abortion right from the rights recognized in the cases on which Roe and Casey rely is something that both those decisions acknowledged: Abortion destroys what those decisions call “potential life” and what the law at issue in this case regards as the life of an “unborn human being.” None of the other decisions cited by Roe and Casey involved the critical moral question posed by abortion. They are therefore inapposite. They do not support the right to obtain an abortion

And finally he dismisses stare decisis.

In this case, five factors weigh strongly in favor of overruling Roe and Casey: the nature of their error, the quality of their reasoning, the “workability” of the rules they imposed on the country, their disruptive effect on other areas of the law, and the absence of concrete reliance.

I found this part bizarre. Alito’s first two factors just reiterate that he disagrees with the original decision, which is a precondition for stare decisis being relevant at all. (If you agree with a precedent, you don’t need a doctrine to tell you to follow it.) His examples of the “unworkability” and “disruptive effect” of the Roe framework (as adjusted by Casey) are mostly examples of state legislatures persistently attempting to find loopholes that allow them to harass women seeking abortions, and engaging in bad-faith efforts to sneak harassment in as health regulations, building codes, and other Trojan horses.

Would Alito find gun-right decisions (like Heller) “unworkable” if blue states persistently harassed gun owners and forced courts to keep striking down bad-faith laws by the dozens year after year? I doubt it.

And as for “reliance”, I look at my own reliance on Roe (which I explained ten years ago): My wife and I planned our life together around the assumption that we would not have children. We took precautions to prevent pregnancy, but ultimately we could not have fully trusted our plans if abortion had not been an option.

This is not something special about us. Around the nation, women are planning their lives and careers based on the belief that they will not have to carry a fetus, give birth, or raise a child until they decide to do so. In a very real sense, women are not equal to men in a world without abortion.

More critically, since any form of birth control can fail, women whose lives will be in danger if they get pregnant will have to give up sex if abortion is not available.

So Alito’s assertion that there are no “reliance interests” in Roe is just absurd. He doesn’t rely on Roe, so he thinks no one does.

The problem with “deeply rooted in this Nation’s history and tradition”. You know what definitely is “deeply rooted in this Nation’s history and tradition”? Sexism, racism, and bigotry of all sorts. If “liberty” is going to be defined by what that word meant when the 14th Amendment passed in 1868, then only straight White Christian men will ever have unenumerated rights protected by substantive due process. Justice Kennedy acknowledged as much in his Obergefell opinion:

If rights were defined by who exercised them in the past, then received practices could serve as their own continued justification and new groups could not invoke rights once denied.

Jill Lepore went further in The New Yorker:

There is nothing in [the Constitution] about women at all. Most consequentially, there is nothing in that document—or in the circumstances under which it was written—that suggests its authors imagined women as part of the political community embraced by the phrase “We the People.” There were no women among the delegates to the Constitutional Convention. There were no women among the hundreds of people who participated in ratifying conventions in the states. There were no women judges. There were no women legislators. At the time, women could neither hold office nor run for office, and, except in New Jersey, and then only fleetingly, women could not vote. Legally, most women did not exist as persons.

… Women are indeed missing from the Constitution. That’s a problem to remedy, not a precedent to honor.

Think about the common-law authorities Alito cites, and some of their other opinions. In addition to opinions about abortion, for example, Sir William Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England also includes this assessment of a wife’s personhood:

By marriage, the husband and wife are one person in law: that is, the very being or legal existence of the woman is suspended during the marriage, or at least is incorporated and consolidated into that of the husband: under whose wing, protection, and cover, she performs every thing; and is therefore called in our law-french a feme-covert; is said to be covert-baron, or under the protection and influence of her husband, her baron, or lord; and her condition during her marriage is called her coverture.

And Thomas Hale, who, in addition to sentencing two women to death for witchcraft, also had a lasting impact on the law unrelated to abortion, which became known Hale’s Principle:

but the husband cannot be guilty of a rape committed by himself upon his lawful wife, for by their mutual matrimonial consent and contract the wife hath given up herself in this kind unto her husband, which she cannot retract.

Lepore notes the opinions that Alito does not cite:

Alito cites a number of eighteenth-century texts; he does not cite anything written by a woman, and not because there’s nothing available. “The laws respecting woman,” Mary Wollstonecraft wrote in “A Vindication of the Rights of Woman,” in 1791, “make an absurd unit of a man and his wife, and then, by the easy transition of only considering him as responsible, she is reduced to a mere cypher.” She is but a part of him. She herself does not exist but is instead, as Wollstonecraft wrote, a “non-entity.”

So Alito’s litany that prior to the 20th century abortion rights can be found in

no state constitutional provision, no statute, no judicial decision, no learned treatise

is much less impressive when you realize that no woman had any input into these documents. I find it hard to argue with Lepore’s conclusion:

To use a history of discrimination to deny people their constitutional rights is a perversion of logic and a betrayal of justice.

How should we justify unenumerated rights? History is a fine tool to use when judging what unenumerated rights the Constitution implicitly guarantees to individuals and groups who were enfranchised and empowered at the time (such as straight White Christian men). But in order to keep those rights from further enlarging the unfair advantages those individuals and groups already have, we need to combine those historical findings with a generous respect for the equal protection of the laws.

Justice Kennedy recognized just such a conjunction of prinicples in Obergefell:

The Due Process Clause and the Equal Protection Clause are connected in a profound way, though they set forth independent principles. Rights implicit in liberty and rights secured by equal protection may rest on different precepts and are not always co-extensive, yet in some instances each may be instructive as to the meaning and reach of the other. In any particular case one Clause may be thought to capture the essence of the right in a more accurate and comprehensive way, even as the two Clauses may converge in the identification and definition of the right.

For example: Do men have a traditional right to bodily autonomy, even when someone else’s life is at stake? Of course they do. American law has never forced a man to, say, donate a kidney to someone who will die without it. That would be absurd. But if a woman can be forced to risk her own lives to save the life of a fetus, does she enjoy the equal protection of the laws? I don’t think so.

Many of the same men who would force a woman to give up months of her life or even risk death for a fetus also believe that the Constitution protects them against the comparatively trivial inconvenience of a vaccine shot that might save not just their own lives, but the lives of the fellow citizens that they might otherwise infect. This is not equality under the law.

And about that history … A number of authors suggest that Alito’s reading of the history of abortion is biased. One of the more amusing examples of the historical acceptance of abortion in America is Ben Franklin’s abortion recipe, which he published in 1748 as part of a textbook.

And a brief prepared for this case by the American Historical Association contradicts Alito:

The common law did not regulate abortion in early pregnancy. Indeed, the common law did not even recognize abortion as occurring at that stage. That is because the common law did not legally acknowledge a fetus as existing separately from a pregnant woman until the woman felt fetal movement, called “quickening,” which could occur as late as the 25th week of pregnancy. This was a subjective standard decided by the pregnant woman alone and was not considered accurately ascertainable by other means.

Are other rights at risk? Alito explicitly denies that his reasoning leads to the end of other rights associated with substantive due process:

As even the Casey plurality recognized, “abortion is a unique act” because it terminates “life or potential life”. … And to ensure that our decision is not misunderstood or mischaracterized, we emphasize that our decision concerns the constitutional right to abortion and no other right. Nothing in this opinion should be understood to cast doubt on precedents that do not concern abortion.

While it is true that lower courts cannot directly quote Alito’s ruling to support eliminating other privacy rights, anti-abortion extremists also describe the pill, Plan B, and IUDs — and basically all birth control other than barrier methods — as “abortificants”. If states can ban abortion, they can ban these as well.

A bill currently advancing through the Louisiana legislature would define personhood as beginning “at fertilization”, which would make the use of an IUD attempted murder. This law would probably pass muster with Alito, who says that abortion laws going forward need only pass a rational basis test, the loosest possible legal standard.

And nothing stops these same five justices from walking the same path for a different issue on a different case. Consider what Alito writes about a right to abortion:

Not only are respondents and their amici unable to show that a constitutional right to abortion was established when the Fourteenth Amendment was adopted, but they have found no support for the existence of an abortion right that predates the latter part of the 20th century — no state constitutional provision, no statute, no judicial decision, no learned treatise.

This statement is equally true if you replace “abortion” with “same-sex marriage” or “interracial marriage” or “sodomy”. Why would the radical conservative justices not make that substitution in some future case?

Vox’ Ian Millhiser points out that Alito has already made a similar argument against same-sex marriage.

Though Alito’s Dobbs opinion largely focuses on why he believes that the right to abortion fails the Glucksberg test, there is no doubt that he also believes that other important rights, such as same-sex couples’ right to marry, also fail Glucksberg and are thus unprotected by the Constitution. Alito said as much in his Obergefell dissent, which said that “it is beyond dispute that the right to same-sex marriage is not among those rights” that are sufficiently rooted in American history and tradition.

Every issue, when you come down to it, is “unique” in some way. If criminalization in 1868 shows that a right does not exist, then clearly the right of consenting adults to choose their own sexual practices, for example, is not “deeply rooted in this Nation’s history and tradition” or “implicit in the concept of ordered liberty”. Neither is the right to marry the person of your choice.

This is where it matters that Alito and his fellow conservative justices made so many misleading and deceptive statements during their confirmation hearings. Could Alito’s statement that he does not “cast doubt on precedents that do not concern abortion” be one more deceptive reassurance that will only last until the five radical justices find a more convenient opportunity to take away other rights that contradict their conservative interpretations of Christianity?

Harvard Law Professor Mary Ziegler thinks it probably is:

The Court can draw whatever distinctions it likes and dodge the cases it doesn’t. But the draft of Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization stresses that states were criminalizing abortion. True enough. But in the late 19th century, Congress passed the Comstock Amendment, which criminalized contraception. States criminalized same-sex intimacy.

The draft suggests that abortion is different because of the state’s impact on fetal life. This language — and the draft’s historically questionable narrative about the doctors who originally pushed to ban abortion — will encourage antiabortion leaders to ask the conservative justices to declare that a fetus is a rights-holding person under the Fourteenth Amendment — and that abortion is unconstitutional in blue as well as red states.

If this is where a final opinion ends up, the Court has painted itself into a corner — and maybe by design. Whether abortion is different or not, the Court will not likely send this back to the states for good. It will simply invite conservatives back for the next round.

In short, anyone who trusts Alito’s statement, and so believes that birth control (Griswold), same sex marriage (Obergefell), interracial marriage (Loving), and homosexuality (Lawrence) are secure, is a fool.

We know who Samuel Alito is, and he is not trustworthy.

Comments

Sent from my iPhone

>

It strikes me that there is an uncanny similarity between the Alito/Supreme Court position on women’s bodies and last week’s Taliban decree that it is ‘required for all respectable Afghan women to wear a hijab’.

Very small point: the best medical understanding of how an IUD works, is that it effectively ‘poisons’ sperm with copper ions, thus preventing fertilization altogether. So by that data, it is not an abortifacient.

Of course, the Texas “heartbeat” (there isn’t one, it’s just an electrical impulse, there isn’t even a single valve yet) law proves that actual data and science do not stop bad laws and bad court decisions.

To have any chance of convincing these folks, you’d have to argue that an IUD NEVER causes the death of a fertilized ovum.

As Charles Roth correctly noted, science does not always have anything to do with it. Three years ago, an Ohio law allowed doctors treating women with an ectopic pregnancy to move a fetus from the Fallopian tubes to the uterus, a technology that DOES NOT EXIST.

It is pretty clear that Alito is inserting his religion into his decision. Any judge with his mental powers knows that the idea a human soul is imparted at fertilization is a religious claim, and not a scientific claim. Indeed it cannot be a scientific claim, because science doesn’t deal with souls. He ignores the long tradition amongst Bible bleievers that the soul was imparted at first breath — at birth. He ignores science regarding acorns not being oak trees. We have living evidence of the reuniting of Church and State right here in Alito’s opinion.

There is no death certificate issued by a county when a woman miscarries in the early weeks of a pregnancy. To me, that indicates that the government doesn’t believe someone has died At the what point in a pregnancy gone wrong, resulting is miscarriage or still birth, would a death certificate be issued?

In Ohio A Fetal Death Cert. is required after 20 wks. gestation.

And what about the 50% or so of fertilized eggs that never implant? The woman cannot know she murdered this person; no pregnancy test would detect this pre-implantation circumstance. These laws are not merely unscientific; they are also laughably silly.

Gambling has become a right since the Roe era as well. How does that stack up to Alito’s reasoning?

I don’t quote myself often, but when I do…

“One more time I’ll tell you what it’s about, as a wannabe genocide scholar…It’s not about sex, it’s not even about religion, it’s only tangentially about the vague definitions of “power”. It’s about what one person or more can assume over another. It’s one man, even on the other side of the globe, assuming primacy over one, ten, 100, a million, more, women. Women he doesn’t know. Women he’s never met. A governor, a judge, a clergyman, a guy in the street. It is the principle tenet of fascism from it’s beginnings in classical Greece, through it’s development in Imperial Rome, “tenderly preserved” like Tiny Tim’s crutches by the Roman Catholic Church, to it’s present-day banality: “I say who you are, what you are worth, and you are mine to master as I please.”

Great work Mr. Muder!

We are all issued birth certificates,..not conception certificates…..And upon the anniversary of our first birth day, we are considered one year old,….not one year and nine months old. Charitably and at best, anti abortion logic is confused.

It’s striking to me that conservatives claim to believe that liberals are “pro-abortion,” but never really consider the importance of choice.

Remember that the opposite of pro-choice isn’t pro-life, it’s anti-choice. And one can implement anti-choice legislation either through having the state force a pregnant woman to carry a fetus to term OR by forcing her to abort the fetus. So why doesn’t anyone on either side of the political isle ever argue, for example, that the law should mandate that anyone under the age of 18 who is pregnant abort their pregnancy? A state imposing that law is perfectly justified following a reversal of Roe v. Wade.

I’d like to see some pro-personal responsibility politician advocate for a pro-abortion policy in their state claiming that it would be profoundly irresponsible to give a 16-year old pregnant girl the right to “choose life” and to carry a pregnancy to term. They could argue that in the modern era, there is no justification whatsoever for a 16-year old to give birth under any circumstances given the data we have on the life outcomes of those situations, on average. It should therefore be illegal.

Turning this issue on its head helps reveal how important choice really is.

Great post! I’m mostly in agreement, but there are two arguments in here I don’t buy, and would seem to prove too much.

On racism and sexism being rooted in our history and law: This line of reasoning seems to ignore that the constitution has been amended at times to address this. The 13th-15th amendments were plainly added for the purpose of updating how the law treats black people, and contra Lepore the 19th amendment is obviously about women. The rights provided by these amendments were explicitly added to the constitution — they are not simply the result of courts discovering one day that it was a moral travesty that these rights were absent. The alternative the argument in this section seems to gesture toward is a world where, were these amendments not to exist, it would be the responsibility of the courts to invent them. I see the moral appeal of this, but what sort of government would we even be if we could expect this of our courts? Effectively a religious theocracy where unaccountable rulers could update the law according to their understanding of morality, it seems?

The other argument I found lacking is this increasingly popular one:

“American law has never forced a man to, say, donate a kidney to someone who will die without it. That would be absurd. But if a woman can be forced to risk her own lives to save the life of a fetus, does she enjoy the equal protection of the laws?”

This analogy fails in a quite crucial way. No one, man or woman, is obligated to donate their own kidney to anyone else, even if the other person will die without it, even if the other person is their own kid. Consider it settled that we have the right to bodily autonomy in this regard. So, since you can rightfully condemn to death another person who needs your kidney and will die without it, do you additionally have the right to stab or poison them? Of course not; that would be absurd, and a violation of their bodily autonomy. But that’s commonly involved in abortion. The reason it’s not murder to not donate your kidney to someone depends quite crucially on the action/inaction distinction, and so for the analogy to extend to abortion you have to treat abortion as inaction rather than action, and I don’t think that makes much sense. I *do* think it makes sense to argue that a fetus (especially a first trimester fetus) should not be understood as morally equivalent to a child and not given the same rights, but the abortion question really does crucially depend on arguing this; there isn’t a particularly compelling way of bypassing the question of whether the fetus has any rights in arguing for abortion rights.

Trackbacks

[…] look at the leaked Alito opinion overturning Roe v Wade through two very different lenses. The other post goes through the text of the opinion and examines its claims and arguments. This one considers the […]

[…] week’s featured posts are “What Alito Wrote” and “Who’s to blame for overturning […]

[…] Justice Alito’s majority opinion striking down Roe v Wade has barely changed since I wrote about the draft that leaked out in May. So I won’t repeat that material, but instead will focus on the […]