The Rahimi case isn’t getting a lot of coverage, because (as an 8-1 victory for common sense), it doesn’t make good clickbait. But the conservative judges are having an important discussion about the future of originalism.

Imagine you’re at a dinner party. On your way back from the bathroom, you happen to overhear a snatch of conversation from the kitchen: Your hosts have been discussing whether to poison your meal, and decide not to.

How should you feel about that? Relieved? Poisoning is a bad thing, and it’s not going to happen to you tonight. Angry? Why? Murder is wrong, and your hosts have decided not to do it. They’ve made the moral choice. Good for them.

Or maybe you focus on this question: Why were they having that conversation to begin with?

The Rahimi case. Now you can imagine how I feel about the outcome of United States v Rahimi, which the Supreme Court announced Friday. They decided that Congress does have the right to pass laws that take guns away from domestic abusers who are under restraining orders. Or, looking at it from the other side of the gun, men who have been judged by a court to pose a credible threat to their intimate partners do not have an absolute right to bear arms.

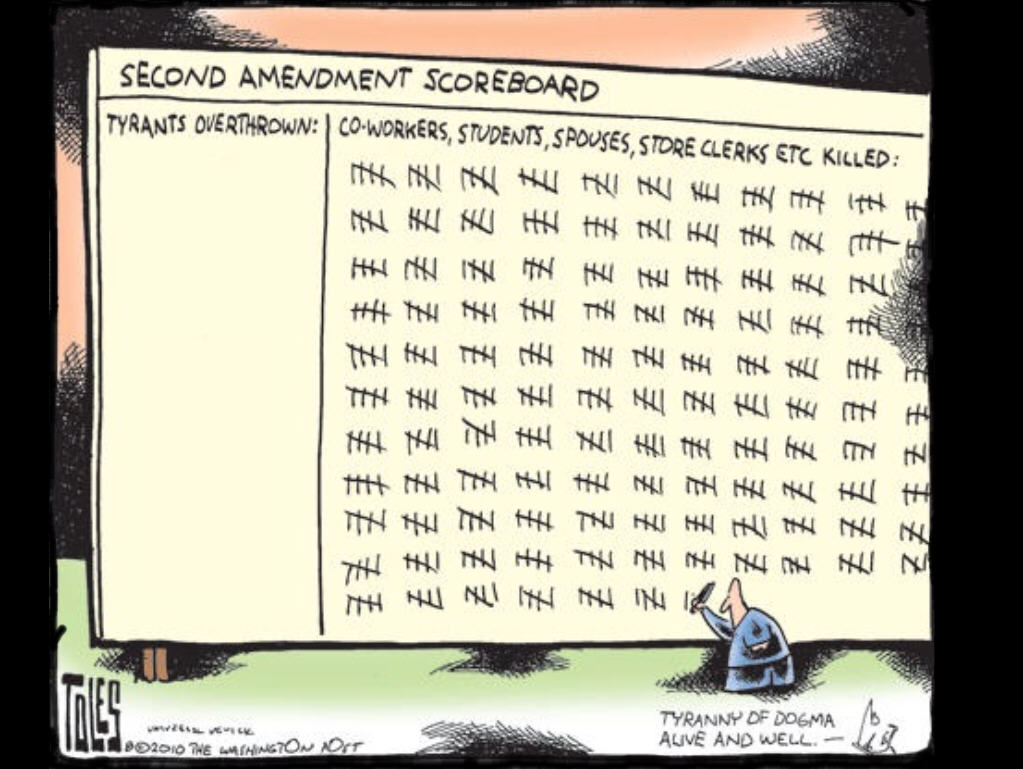

Good job, justices. With only one dissent (corrupt Clarence Thomas) they made the right call. Good for them. But why were they having that conversation to begin with? Why did anyone think that in one of the most obvious potential-murder situations imaginable [1], our legal system is banned from offering a woman even the simplest kind of protection?

In particular, why did anyone think it might be unconstitutional to disarm Zackey Rahimi, who perfectly exemplifies why domestic abuse laws exist? Rahimi didn’t just threaten the estranged mother of his child with a gun and then violate the restraining order she got for her own (and her child’s) protection, he also was involved in several other shooting incidents, some related to his personal anger-control issues and others stemming from his professional role as a drug dealer.

That guy. Even worse, Rahimi was making what is known as a facial challenge to the law disarming domestic abusers. In ordinary English, the law is unconstitutional on its face; there are no conceivable situations in which the law could be applied without violating the Second Amendment.

Why would anybody take that claim seriously enough that the Supreme Court should have to decide it?

Two reasons, really:

- Two years ago, in the Bruen case (which was announced almost simultaneously with the Dobbs decision reversing Roe v Wade), the Court proclaimed a new test for Second Amendment constitutionality that called nearly all American gun laws into question.

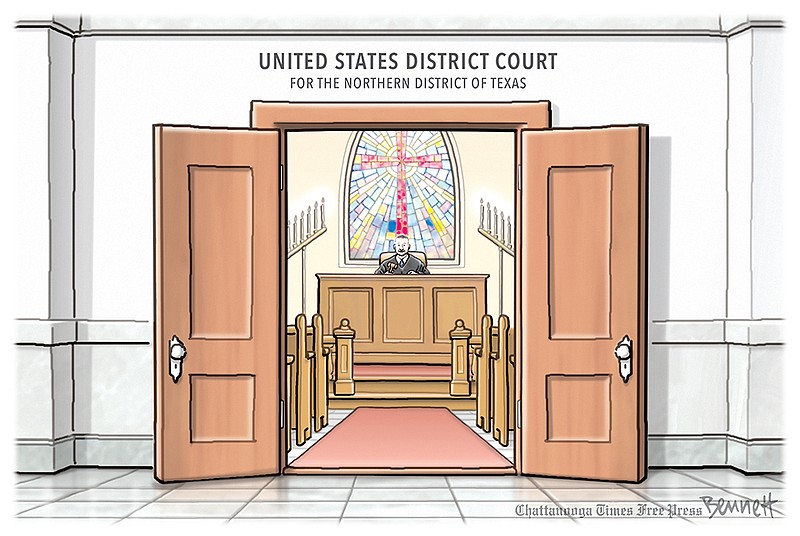

- And then in 2023, one of the few courts even more batshit crazy than the Supreme Court itself (the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals) applied the Bruen test to Zackey Rahimi and ordered the government to give him back his guns.

So that’s where we were as of Thursday: Unless the Court acted, Rahimi was getting his guns back, and the mother of his child had just better watch out. Not only wouldn’t the government help her, it was constitutionally barred from ever doing so, no matter what Congress or any other elected officials might think.

The Bruen test. You’ll never guess who wrote the majority opinion in Bruen. OK, maybe you will: corrupt Clarence Thomas, with the backing of the other five conservative justices, including all three of the Trump justices. The heart of that ruling is this:

[W]e hold that when the Second Amendment’s plain text covers an individual’s conduct, the Constitution presumptively protects that conduct. The government must then justify its regulation by demonstrating that it is consistent with the Nation’s historical tradition of firearm regulation. Only then may a court conclude that the individual’s conduct falls outside the Second Amendment’s “unqualified command.”

In a hearing before the Fifth Circuit, the government offered various colonial or founding-era analogues of the domestic abuse law in question, and the judges found none of them quite analogous enough. Justice Sotomayor’s concurrence with Friday’s decision explained why this might be:

Given the fact that the law at the founding was more likely to protect husbands who abused their spouses than offer some measure of accountability, see, e.g., R. Siegel, “The Rule of Love”: Wife Beating as Prerogative and Privacy, 105 Yale L. J. 2117, 2154–2170 (1996), it is no surprise that that generation did not have an equivalent to [the law Rahimi has challenged]. Under the dissent’s [i.e. Thomas’] approach, the legislatures of today would be limited not by a distant generation’s determination that such a law was unconstitutional, but by a distant generation’s failure to consider that such a law might be necessary. History has a role to play in Second Amendment analysis, but a rigid adherence to history, (particularly history predating the inclusion of women and people of color as full members of the polity), impoverishes constitutional interpretation and hamstrings our democracy.

Putting her point more bluntly: When the Second Amendment was ratified in 1791, women were not really people, and wives in particular were subject to the whims of their husbands in ways we no longer accept. So you’re not going to find much in the way of domestic-violence legislation from that era, much less laws disarming domestic abusers. But that’s because the founding generation just didn’t think domestic violence was a problem worthy of government action, not necessarily because they endorsed the right of dangerous people to be armed.

But the Fifth Circuit didn’t look at it that way: Nobody disarmed the Zackey Rahimis of 1791, so we shouldn’t be able to disarm Zackey Rahimi today.

Originalism. Like Justice Alito’s majority opinion in Dobbs, Thomas’ opinion in Bruen (and his dissent in Rahimi) is an example of a method of constitutional interpretation known as originalism. All six conservative justices claim to be originalists. In his Rahimi concurrence, Justice Kavanaugh restates the fundamental notion of originalism:

The first and most important rule in constitutional interpretation is to heed the text—that is, the actual words of the Constitution—and to interpret that text according to its ordinary meaning as originally understood.

Originalism was popularized by the late Justice Anton Scalia, who spent most of his career in the minority, writing rousing dissents. But in recent years, originalists have become the majority on the Court, raising a significant issue: How do you turn a critical theory into a governing theory? [2] Most of the time, Scalia didn’t have to worry about the practical implications of his views, because they weren’t going to be adopted anyway. Now, though, originalists have to be concerned with consequences, like arming the Zackey Rahinis of the world.

In arguing against originalist interpretations, it’s important to understand precisely where originalists are and aren’t coming from. The point isn’t that the Founders were divinely inspired lawgivers like Moses (though some conservatives do believe this). Originalism says something more fundamental about the basis of law in a constitutional democratic republic like the United States: For laws to be binding on the People, the People must at some point have accepted that burden. So any legitimate originalist analysis [3] revolves around the questions: When did the People accept this restriction or give the government this power?

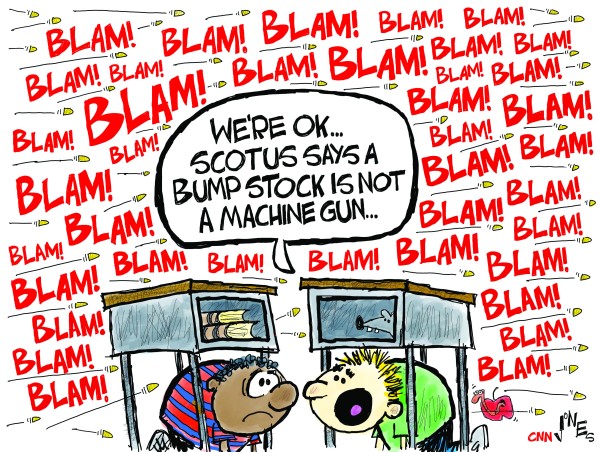

So, for example, look back at another case in this term: Cargill, the bump-stock case. That case revolves around two questions: When did the American people give up their right to own machine guns? And what did they think a “machine gun” was at that time? The answer to the first question is that (through their elected representatives) they gave up that right in the National Firearms Act of 1938. The NFA contains a definition of machine gun, which the justices then argue about.

The blurring effects of time. The root problem with originalism is that a text’s “ordinary meaning as originally understood” is way more complicated than Kavanaugh makes it sound. Individual people living in the same era think at different levels of abstraction. So consider the “bear arms” phrase in the Second Amendment. To one American living in 1791, the Amendment might apply abstractly to all “bearable arms” — any weapon that can be carried by one person. [4] His neighbor might have a more specific way of thinking, and so picture “arms” as the weapons he has seen or handled personally: flintlocks, sabres, and bows. A third citizen might think about the effects of arms: To him, the Amendment applies to anything that does roughly the same amount of damage as flintlocks, sabres, and bows. He might not have been picturing African blowguns, but if you described them to him he would probably see them as “arms” as well.

At that one particular moment in 1791, those three ways of thinking were in alignment: The arms that could be borne were flintlocks, sabres, and bows, but not cannons. The three citizens have different mental notions, but they will agree on any specific case that comes up.

But as the world changes, notions that once agreed come out of alignment. Transport our three founding-era citizens to World War II and show them a bazooka. The first citizen sees a weapon bearable by one person, the second sees something totally unlike any weapon he has used, and the third sees something more analogous to a cannon than a flintlock. So what is the “original meaning” of Second Amendment “arms” as applied to a bazooka?

That’s why our jurisprudence is so inconsistent in its originalism. (My advice: Don’t try to buy a bazooka.) Take the NFA of 1938 for example. Our first citizen looks at a 1938 Thompson submachine gun (or our era’s combat-ready M-16) and sees a bearable weapon, so to him the NFA’s ban on such weapons is clearly unconstitutional. But none of our current “originalist” justices took that position in Cargill.

The blurring legal environment. Sometimes what changes isn’t technology, but the context of other laws that surround a given law. That’s what happened with same-sex marriage. The Obergefell decision that legalized same-sex marriage nationally in 2015 was based on the 14th Amendment, which was ratified in 1868. [5]

But did the people of 1868 or their elected representatives realize they were legalizing same-sex marriage? Of course not. In the legal environment of the time, same-sex marriage didn’t even make sense. At the time, husbands and wives had different rights and responsibilities under the law, so “Which one of you is the husband and which one is the wife?” was a legitimate question. Also, men had more legal rights than women — most obviously the right to vote, but many others as well. So all opposite-sex households had one vote, but a same-sex household had either zero votes or two. How could that be justified?

By 2015, though, all those legal problems had gone away, for reasons that had nothing to do with homosexuality. Under the law, there are two spouses with legal equality, and neither role requires any special rights only available to one gender or the other. So the only reason to write marriage laws restricted to opposite-sex couples is prejudice against same-sex couples — something “equal protection of the laws” doesn’t allow.

Americans of 1868 couldn’t have foreseen how “equal protection of the laws” would apply to marriage in 2015. But they understood what “equal protection” meant as a principle, and they agreed to it.

Back to Rahimi. Except for Thomas himself, all the justices — liberal and conservative alike — recognize that the originalist logic of Bruen has led the Court to the edge of an abyss: Rahimi should get his guns back. This obviously is a bad outcome, and who knows what worse monsters might also regain their arms and go on to murder their intimate partners or ex-intimate partners? This result is not only bad in itself, but — like Dobbs — will incite a voter backlash against the Court, and against the Republican Party that appointed this conservative majority.

That majority, above all, is partisan. Thomas and Alito clearly want to retire, but will only do so if a Republican president can replace them. The others (with the possible exception of Barrett, who hasn’t done enough yet to earn my negative judgment) enjoy being in the majority and don’t want a re-elected President Biden to shrink that majority by appointing liberals.

Possibly even worse is the effect Bruen has had on the lower courts. The standard of keeping the laws “consistent with the Nation’s historical tradition of firearm regulation” is not only impossibly vague, but the example Bruen sets — cherry-pick history until you get the result you want — invites the worst kind of judicial activism.

Justice Jackson (who hadn’t joined the Court yet when Bruen was decided) lays this out as politely as possible.

This case highlights the apparent difficulty faced by judges on the ground. Make no mistake: Today’s effort to clear up “misunderst[andings],” [from Roberts’ majority opinion] is a tacit admission that lower courts are struggling. In my view, the blame may lie with us, not with them.

The message that lower courts are sending now in Second Amendment cases could not be clearer. They say there is little method to Bruen’s madness. It isn’t just that Bruen’s history-and-tradition test is burdensome (though that is no small thing to courts with heavier caseloads and fewer resources than we have). The more worrisome concern is that lower courts appear to be diverging in both approach and outcome as they struggle to conduct the inquiry Bruen requires of them. Scholars [in an amicus brief on this case] report that lower courts applying Bruen’s approach have been unable to produce “consistent, principled results,” and, in fact, they “have come to conflicting conclusions on virtually every consequential Second Amendment issue to come before them”.

So Bruen needs to be fixed somehow, or at least reined in. But how?

Liberal interpretation. Everyone on the Court is an originalist up to a point: If the text of a law is clear, if its “ordinary meaning as originally understood” can be ascertained, and the varied understandings of people at the time are still more-or-less in alignment, then that well-understood text should be respected. If such a law needs to be fixed according to our current notions of justice, Congress should do it, not the Court.

Conservatives claim liberals don’t believe this [6], but we do.

On most issues controversial enough to reach the Supreme Court, though, liberals recognize that there is no “original understanding” that covers the contemporary situation. (See the examples above.) And yet there is a case that needs to be decided: Rahimi either gets his guns back or he doesn’t.

To state the liberal view more simplistically than probably any of the current liberal justices would: Liberals want to give the original lawmakers the benefit of the doubt. Maybe they couldn’t have foreseen the current situation, but they didn’t intend for us to do something stupid with their words. And while much has changed since the 1700s — women and the non-European races have become people, as Sotomayor points out — certain abstract notions of justice are closer to timeless, and are still more-or-less the same. So we can use those shared values to update our interpretation of the text.

Ideally, the most important texts come up fairly often, so that the record of judicial precedents represents a continuous updating rather than an abrupt break with the past (as Dobbs, Bruen, and Heller were). Like the laws themselves, precedents should be read generously, because the justices of the past also wouldn’t want us to do something stupid with their words.

Of course, this approach requires that current justices have some measure of wisdom and aren’t too humble to use it. That openly confident wisdom is anathema to originalists, who insist that any application of contemporary wisdom must happen covertly, by manipulating history and then claiming to follow it.

Originalism trying to fix itself. Every conservative justice but Alito wrote an opinion on this case. Thomas’ lonely dissent doubles down on Bruen: If the logic of Bruen sends us over a cliff, then here we go. But the other four aren’t willing to jump with him, and feel obligated to explain why not. All of them are sneaking some version of liberal interpretation into their thinking, while denying that they do so.

Roberts’ majority opinion claims that a law can be “consistent with the Nation’s historical tradition of firearm regulation” even if there is no exact parallel, as long as it is analogous to laws from the colonial or founding eras. How close does the analogy need to be? How many parallel regulations establish a “tradition” rather than an anomaly? He doesn’t precisely say. The point is to get enough wiggle room that we don’t have to give back Rahimi’s guns, an outcome that violates “common sense”.

Taken together, the surety and going armed laws confirm what common sense suggests: When an individual poses a clear threat of physical violence to another, the threatening individual may be disarmed.

Such an appeal to contemporary common sense clearly doesn’t sit well with the other conservative justices, who have to write concurrences to put their own spin on it. Kavanaugh’s opinion in particular is a long and fairly dull exposition of originalism that rarely mentions the current case. (As I read, I kept saying “Dude, write a textbook.”) To me, he seems to need to repledge his fealty to originalism precisely because he knows he’s violating it.

The only conservative concurrence that seems honest to me is Barrett’s. (I am developing a grudging affection for Barrett. She’ll probably disillusion me soon, but I have to give credit where it’s due.) Like Jackson, she recognizes that lower courts have had trouble applying Bruen, as well as the inherent limitations of the historical method Kavanaugh extols at such length.

[I]mposing a test that demands overly specific analogues has serious problems. To name two: It forces 21st-century regulations to follow late-18th-century policy choices, giving us “a law trapped in amber.” And it assumes that founding-era legislatures maximally exercised their power to regulate, thereby adopting a “use it or lose it” view of legislative authority. Such assumptions are flawed, and originalism does not require them.

“Analogical reasoning” under Bruen demands a wider lens: Historical regulations reveal a principle, not a mold.

Examining founding-era firearms regulations reveals the “contour” of the right the Founders thought they were recognizing, but doesn’t always lay down its precise terms. Barrett recognizes that being a judge requires applying a certain amount of wisdom to past examples, to draw out the abstract principles behind them. It’s not just “calling balls and strikes” as Roberts claimed at his confirmation hearing and Kavanaugh endorsed in his concurrence. She ends up deciding that the majority opinion in this case “settles on just the right level of generality”, and so she concurs.

I read that as a statement of confidence in her contemporary wisdom, not an effort to hide her judgment behind a fog of historicism.

Conclusion. The Rahimi case is not getting a lot of press coverage, largely because it came to a common-sense conclusion: Rahimi (and other malefactors like him) shouldn’t be armed. It is within the power of Congress and state legislatures to make such decisions.

But the conservative judges are subtly arguing about how to sneak contemporary wisdom (sometimes disguised as “common sense”) back into judicial reasoning. As a governing theory, originalism will have to recognize that the wisdom of the past does not solve all our problems. At some point, judges have be judicious.

[1] According to the Department of Justice:

Of the estimated 4,970 female victims of murder and nonnegligent manslaughter in 2021, data reported by law enforcement agencies indicate that 34% were killed by an intimate partner … Overall, 76% of female murders and 56% of male murders were perpetrated by someone known to the victim. About 16% of female murder victims were killed by a nonintimate family member—parent, grandparent, sibling, in-law, and other family member

[2] This problem parallels the one in the House of Representatives, where MAGA rebels suddenly have real power.

[3] I use the word legitimate because, as I’ve stated in other posts, I don’t believe that most originalist arguments are made in good faith. By cherry-picking historical examples and engaging in opportunistic reasoning no historian studying that era would vouch for, a judge can almost always find an “originalist” justification for whatever conclusion he wants to come to.

Justice Alito’s majority opinion in Dobbs, in my opinion, was an example of this kind of bad-faith historicism. And so was Justice Scalia’s opinion in 2008’s Heller case, which (as Justice Jackson puts it in her concurrence) “unearthed” a new individual right to bear arms, upsetting a consensus interpretation of the Second Amendment that Justice Breyer’s dissent in Heller claimed “ha[d] been considered settled by courts and legislatures for over two centuries”.

Justice Kavanaugh can’t admit that Scalia invented his Heller interpretation out of nothing, but does say: “Second Amendment jurisprudence is still in the relatively early innings, unlike the First, Fourth, and Sixth Amendments, for example. That is because the Court did not have occasion to recognize the Second Amendment’s individual right until recently.”

[4] This is the position Justice Scalia laid out in Heller:

the Second Amendment extends, prima facie, to all instruments that constitute bearable arms, even those that were not in existence at the time of the founding.

[5] Justice Kennedy’s majority opinion rooted his argument in the 14th Amendment’s Due Process clause, but (like some of the concurring justices) I think the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of “the equal protection of the laws” is a cleaner justification.

[6] Kavanaugh’s concurrence warns against “an approach where judges subtly (or not so subtly) impose their own policy views on the American people”, which he sees as the only alternative to originalism’s historical method of interpreting “vague” text.

:format(webp):no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/18929874/8_5_Gun_Violence__1_.png)

:format(webp):no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/10259683/mother_jones_gun_deaths_by_state.png)