Scrapping abortions rights got the headlines. But don’t ignore the Court’s assault on gun regulations and the separation of church and state.

Late June tends to be a big time for the Supreme Court. Like freshmen who have put off writing their term papers until the last minute, the Court typically unleashes a flurry of decisions just before leaving town for the summer.

The end of this term has been more significant than most. Last week, three major decisions were published, along with several lesser decisions. The Dobbs decision reversing Roe v Wade was immediately consequential, as abortion has already effectively become illegal in a number of states, with more to follow soon. But it also laid the groundwork for future decisions reversing a number of rights: the right to marry someone of the same sex or a different race, to access contraception, or to choose (with your consenting partner) your own sexual practices.

The week’s other two decisions had fewer immediate consequences, but similarly looked like the first steps down a long road. Carson v Makin directly affects only a few families in rural Maine, but announces the Court’s intention to drastically redraw the line between Church and State. NY State Rifle & Pistol v Bruen tosses out a New York gun regulation that has stood for a century, but similarly calls all gun regulations into question.

Let’s take them one by one.

Abortion. Justice Alito’s majority opinion striking down Roe v Wade has barely changed since I wrote about the draft that leaked out in May. So I won’t repeat that material, but instead will focus on the concurrences and dissents from other justices.

Justice Alito’s majority opinion tried to minimize the consequences of this decision, which on the surface only [only!] reversed Roe, but also created a blueprint for throwing out all the substantive-due-process rights. Justice Thomas, on the other hand was explicit about where he wants the Court to go next:

in future cases, we should reconsider all of this Court’s substantive due process precedents, including Griswold, Lawrence, and Obergefell. Because any substantive due process decision is “demonstrably erroneous,”, we have a duty to “correct the error” established in those precedents. After overruling these demonstrably erroneous decisions, the question would remain whether other constitutional provisions guarantee the myriad rights that our substantive due process cases have generated.

Thomas forgot to mention one other substantive-due-process case: Loving v Virginia, which makes his own interracial marriage legal. (I can see how that might start a difficult conversation: “Sorry, honey, but we were never really married.”) Given the anti-miscegenation laws that existed when the 14th Amendment passed in 1868, it’s hard to see how Loving survives the kind of historical analysis the Court did this week in both Dobbs and Bruen.

Leaning the other way, Justice Kavanaugh not only ignored future reversals, but tried to gloss over the radical nature of this one:

On the question of abortion, the Constitution is therefore neither pro-life nor pro-choice. The Constitution is neutral and leaves the issue for the people and their elected representatives to resolve through the democratic process in the States or Congress—like the numerous other difficult questions of American social and economic policy that the Constitution does not address.

The obvious implication of that statement is that Kavanaugh would not overrule Congress if it did codify reproductive rights. However, given how duplicitous Kavanaugh has already been on this issue, I wouldn’t count on him following through if such a case reached the Court.

He also waxed philosophical:

The Constitution does not grant the nine unelected Members of this Court the unilateral authority to rewrite the Constitution to create new rights and liberties based on our own moral or policy views.

I’ll be interested to see if Kavanaugh stands by this position the next time a corporate personhood case comes before the Court. The Constitution says nothing about corporations, and yet conservative judges have had no trouble reading between the lines to find “new rights and liberties” for these wealthy and immortal beings.

As I predicted in March, Chief Justice Roberts concurred in upholding Mississippi’s ban on abortions after 15 weeks, but not in overturning Roe completely.

Our abortion precedents describe the right at issue as a woman’s right to choose to terminate her pregnancy. That right should therefore extend far enough to ensure a reasonable opportunity to choose, but need not extend any further—certainly not all the way to viability. Mississippi’s law allows a woman three months to obtain an abortion, well beyond the point at which it is considered “late” to discover a pregnancy.

That’s typical Roberts, as you’ll see below in the Carson case. He also would destroy Roe, but do it over a period of years by pecking it to death. In this dissent, he makes a doctrine out of that approach:

If it is not necessary to decide more to dispose of a case, then it is necessary not to decide more.

Going back to the corporate personhood example, Roberts didn’t recommend this kind of restraint in Citizens United.

The Court’s three liberal justices — Breyer, Kagan, and Sotomayor — wrote a common dissent. Interestingly, they agreed with Thomas that abortion rights are tied to all the other substantive-due-process rights.

The lone rationale for what the majority does today is that the right to elect an abortion is not “deeply rooted in history”: Not until Roe, the majority argues, did people think abortion fell within the Constitution’s guarantee of liberty. The same could be said, though, of most of the rights the majority claims it is not tampering with. The majority could write just as long an opinion showing, for example, that until the mid-20th century, “there was no support in American law for a constitutional right to obtain [contraceptives].” So one of two things must be true. Either the majority does not really believe in its own reasoning. Or if it does, all rights that have no history stretching back to the mid-19th century are insecure. Either the mass of the majority’s opinion is hypocrisy, or additional constitutional rights are under threat. It is one or the other.

The dissent challenges the legitimacy of ignoring stare decisis to reverse the Roe and Casey precedents.

No recent developments, in either law or fact, have eroded or cast doubt on those precedents. Nothing, in short, has changed. … The Court reverses course today for one reason and one reason only: because the composition of this Court has changed. Stare decisis, this Court has often said, “contributes to the actual and perceived integrity of the judicial process” by ensuring that decisions are “founded in the law rather than in the proclivities of individuals.” Today, the proclivities of individuals rule.

It attacks Alito’s history-alone reasoning. If “liberty” means exactly what it did in 1868, that has a lot of unfortunate consequences, particularly for women.

The Court [in Casey] understood, as the majority today does not, that the men who ratified the Fourteenth Amendment and wrote the state laws of the time did not view women as full and equal citizens. A woman then, Casey wrote, “had no legal existence separate from her husband.” Women were seen only “as the center of home and family life,” without “full and independent legal status under the Constitution.” But that could not be true any longer: The State could not now insist on the historically dominant “vision of the woman’s role.”

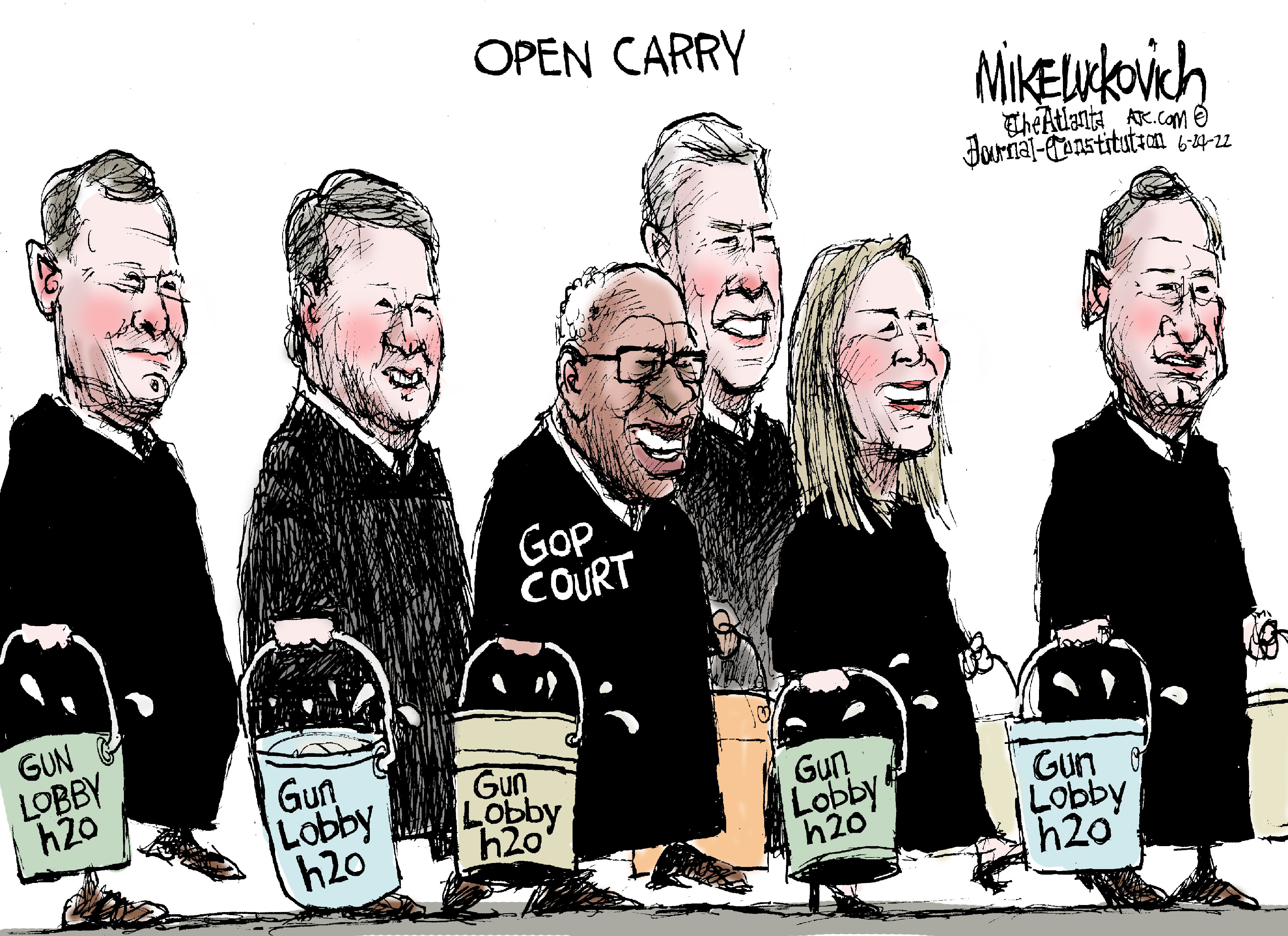

Guns. In Bruen, Justice Thomas writes for the six conservative justices. Thomas is the justice whose thought process seems most alien to me, and here he loses me early on:

In keeping with Heller, we hold that when the Second Amendment’s plain text covers an individual’s conduct, the Constitution presumptively protects that conduct.

Heller is the 2008 case in which Justice Scalia invented an individual right to bear arms, independent of any notion of “a well-regulated militia”, as if the Founders just threw that phrase into the Second Amendment on a whim.

Judges and legal scholars before Scalia had laughed at this interpretation, which had not figured in any previous Supreme Court decision since the beginning of the Republic. In 1990, retired Chief Justice Warren Burger, who had been appointed by Richard Nixon and at the time was not anyone’s idea of a liberal, called such an interpretation of the Second Amendment “a fraud on the American public“. John Paul Stevens, who wrote the primary dissent in Heller, called it “the Supreme Court’s worst decision of my tenure“.

And then we get to “the Second Amendment’s plain text”. I have explained previously (and at length) why I don’t think the text of the Second Amendment means anything at this point. (Briefly, the Founders’ vision of the role of the militia bears no resemblance to any institution that currently exists: not the National Guard, and certainly not self-appointed yahoos who run around in the woods wearing camo. History just went a different way. The Second Amendment, basically, is a signpost on a road not taken.) So the idea that the Second Amendment has a “clear text” that “covers” something in today’s world — that’s just wrong. If we can’t repeal it and start over, the most sensible approach would be to ignore it.

Anyway, Heller is the archetypal “originalist” decision: It does some grammatical sophistry that has basically nothing to do with the issues the Founders actually cared about, and then — surprise! — deduces that the Founders agreed with the author.

This is what Thomas is building on.

Thomas follows the statement above with:

The government must then justify its regulation by demonstrating that it is consistent with the Nation’s historical tradition of firearm regulation. Only then may a court conclude that the individual’s conduct falls outside the Second Amendment’s “unqualified command.”

The regulation in question in this case is New York’s state law that requires gun owners to have a license, and which denies licenses for people to carry guns outside their homes unless they “demonstrate a special need for self-protection distinguishable from that of the general community.” The two New Yorkers bringing suit claim that it should be up to them to decide if they need a gun for self-defense, not up to the state.

Thomas then has to judge whether this regulation is “consistent with the Nation’s historical tradition of firearm regulation”. But he then edits that history in a very convenient way: Pre-colonial English history is too early to matter (though it wasn’t when assessing abortion laws in Dobbs). Gun regulations in the Wild West come too late. Even colonial and federal-era history can be swept away with the proper hand-waving.

Thus, even if these colonial laws prohibited the carrying of handguns because they were considered “dangerous and unusual weapons” in the 1690s, they provide no justification for laws restricting the public carry of weapons that are unquestionably in common use today.

And two post-Civil-War cases in Texas “support New York’s proper-cause requirement”, but they can be dismissed as “outliers”. When the Kansas Supreme Court upheld a “complete ban on public carry enacted by the city of Salina in 1901”, its decision was “clearly erroneous”. And the New York law Thomas is overturning was passed in 1911. (Justice Breyer’s dissent correctly sums up Thomas’ historical analysis as “a laundry list of reasons to discount seemingly relevant historical evidence.” The dissent in Dobbs makes fun of how Thomas’ cramped view of history in this case contrasts with Alito’s expansive citation of sources back to the Middle Ages in Dobbs. Thomas, naturally, signed on to Alito’s opinion, and his concurrence did not correct Alito’s historical analysis.)

Thomas’ whole historical method ignores the possibility that early American legislators believed they had a perfect right to regulate firearms, but didn’t see any special need at the time. (Breyer: “In 1790, most of America’s relatively small population of just four million people lived on farms or in small towns. Even New York City, the largest American city then, as it is now, had a population of just 33,000 people. Small founding-era towns are unlikely to have faced the same degrees and types of risks from gun violence as major metropolitan areas do today, so the types of regulations they adopted are unlikely to address modern needs.”)

And so, having adopted Heller’s interpretation of the Second Amendment and eliminated any conflicting examples from consideration, Thomas reaches his conclusion.

At the end of this long journey through the Anglo-American history of public carry, we conclude that respondents have not met their burden to identify an American tradition justifying the State’s proper-cause requirement. The Second Amendment guaranteed to “all Americans” the right to bear commonly used arms in public subject to certain reasonable, well-defined restrictions. Those restrictions, for example, limited the intent for which one could carry arms, the manner by which one carried arms, or the exceptional circumstances under which one could not carry arms, such as before justices of the peace and other government officials. Apart from a few late-19th-century outlier jurisdictions, American governments simply have not broadly prohibited the public carry of commonly used firearms for personal defense. Nor, subject to a few late-in-time outliers, have American governments required law-abiding, responsible citizens to “demonstrate a special need for self-protection distinguishable from that of the general community” in order to carry arms in public.

Justice Breyer’s dissent raises the central failing of Thomas’ dogmatic approach.

The question before us concerns the extent to which the Second Amendment prevents democratically elected officials from enacting laws to address the serious problem of gun violence. And yet the Court today purports to answer that question without discussing the nature or severity of that problem.

In other words, Thomas loses himself in estimating how many angels could dance on a pinhead in the 1790s, without any concern for what is happening today. (Alito’s concurrence berates Breyer for even daring to consider the present-day problem the law in question is trying to address.) Breyer finds that “decisions about how, when, and where to regulate guns [are] more appropriately legislative work”, and that judges should show “modesty and restraint” in overruling legislatures who take on that work. And he raises this key question:

[W]ill the Court’s approach permit judges to reach the outcomes they prefer and then cloak

those outcomes in the language of history?

I think we know the answer to that one.

Church and State. Because John Roberts doesn’t sign on to decisions like Alito’s reversal of Roe, he has gotten an image as the “moderate” on the Court. I don’t think that’s exactly true. Roberts is every bit as radical as the five who signed Alito’s opinion. He just moves towards his extreme goals in a stealthier, more step-by-step fashion. Roberts is like the thief who doesn’t strip your whole orchard in one night; but he leaves a hole in the fence and keeps coming back.

Campaign finance is a good example. Roberts didn’t destroy Congress’ ability to control political contributions in one fell swoop. He ate away at it over a period of years.

His majority opinion in Carson v Makin is similarly one of a series of cases that eats away at separation of church and state. On the surface, this decision doesn’t do much: A handful of families who live in rural areas of Maine will be able to get state support to send their children to conservative Christian schools, in spite of the Maine legislature’s attempt not to fund such schools. (And even they won’t get support for the schools they want, because Maine’s law also disqualifies schools that discriminate against gays and lesbians.)

To get that tiny result, though, Roberts blows a big hole in the wall between church and state. New cases will be coming through that hole for years to come, and the principles established in Carson will funnel more and more public funding to the Religious Right.

Here’s the background: Some rural areas of Maine have so few students that it’s not worth supporting a public high school. Instead, some of them contract with high schools in neighboring districts to take their students. But some don’t even do that. If you live in one of those, you can get tuition reimbursement from the state to send your children to a private high school that meets certain requirements. One requirement is that the school be “nonsectarian”. That condition was added in 1981, after the state attorney general ruled that paying tuition to a sectarian school would violate the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment.

Maine has a fairly narrow definition of “sectarian”. It’s OK for a school to be founded by or associated with a church or other religious organization. But public money was banned from going to a school which

in addition to teaching academic subjects, promotes the faith or belief system with which it is associated and/or presents the material taught through the lens of this faith.

The two families that brought suit against this policy live in Glenburn (population 4,648) and Palermo (1,570). They want Maine to help them pay tuition to schools that clearly are sectarian. For example, one of the schools, Temple Academy, has as its mission statement:

Temple Academy exists to know the Lord Jesus Christ and to make Him known through accredited academic excellence and programs presented through our thoroughly Christian Biblical world view.

It goes on to pledge

To provide a sound academic education in which the subject areas are taught from a Christian point of view.

To help every student develop a truly Christian world view by integrating studies with the truths of Scripture.

So Temple is not like a nominally Catholic or Baptist school where students of other faiths might opt out religion classes or worship services. Students who attend any classes at all are being indoctrinated in a conservative Christian worldview, and part of every teacher’s job is to promote a particular version of Christianity.

Also, the Maine law is not like a voucher program, where the legislature delegates choice of schools to parents, understanding that some parents will choose sectarian schools. Maine’s legislature tried NOT to fund religious indoctrination; but Roberts’ decision says that it MUST.

This is new, and it is radical.

Justice Breyer’s dissent (Breyer, who is retiring and will be replaced next term by Ketanji Brown Jackson, is going out with a bang) is a good introduction to how the Court has historically interpreted the First Amendment, which bars any government “establishment of religion” but also guarantees individual citizens “free exercise” of their religious faith. Breyer says that these two clauses are “often in tension” but express “complementary values”. Quoting previous Court decisions, Breyer imagines what motivated the amendment’s two religion clauses.

Together they attempt to chart a “course of constitutional neutrality” with respect to government and religion. They were written to help create an American Nation free of the religious conflict that had long plagued European nations with “governmentally established religion[s].” Through the Clauses, the Framers sought to avoid the “anguish, hardship and bitter strife” that resulted from the “union of Church and State” in those countries.

“Conflict” is a bit of an understatement here. In England, the Anglican/Catholic/Puritan struggle dominated the 1600s, resulting in the beheading of Charles I, a long civil war, and the Glorious Revolution of 1688. On the Continent, the Thirty Years War killed at least 4.5 million people. The Founders knew this history and desperately wanted to avoid repeating it.

Previous Courts held that the tension between the two religion clauses created “play in the joints”. In other words, states had room to navigate between them. One state might choose to draw the line in a different place than another.

States enjoy a degree of freedom to navigate the Clauses’ competing prohibitions.

Roberts started taking that freedom away when he wrote the majority opinion in the 2017 Trinity Lutheran case, where Missouri was forced to include religious schools in a grant program to make playgrounds safer. Breyer can live with that outcome (in 2017 he wrote a partial concurrence), but doesn’t think that decision forces this one.

Any Establishment Clause concerns arising from providing money to religious schools for the creation of safer play yards are readily distinguishable from those raised by providing money to religious schools through the program at issue here—a tuition program designed to ensure that all children receive their constitutionally guaranteed right to a free public education. After all, cities and States normally pay for police forces, fire protection, paved streets, municipal transport, and hosts of other services that benefit churches as well as secular organizations. But paying the salary of a religious teacher as part of a public school tuition program is a different matter.

It’s striking that in this case (as in the gun case above) it is Breyer and the liberals, not Roberts (or Thomas) and the conservatives, who are defending states rights.

We have never previously held what the Court holds today, namely, that a State must (not may) use state funds to pay for religious education as part of a tuition program designed to ensure the provision of free statewide public school education.

The cases Roberts cites as precedents, Breyer says, don’t justify this shift from permission to requirement.

In the majority’s view, the fact that private individuals, not Maine itself, choose to spend the State’s money on religious education saves Maine’s program from Establishment Clause condemnation. But that fact, as I have said, simply permits Maine to route funds to religious schools. It does not require Maine to spend its money in that way.

This particular decision may not affect many Americans. But Breyer sees clearly where Roberts is headed.

What happens once “may” becomes “must”? Does that transformation mean that a school district that pays for public schools must pay equivalent funds to parents who wish to send their children to religious schools? Does it mean that school districts that give vouchers for use at charter schools must pay equivalent funds to parents who wish to give their children a religious education? What other social benefits are there the State’s provision of which means—under the majority’s interpretation of the Free Exercise Clause—that the State must pay parents for the religious equivalent of the secular benefit provided? The concept of “play in the joints” means that courts need not, and should not, answer with “must” these questions that can more appropriately be answered with “may.”

And doesn’t Roberts’ policy implicitly favor more popular religions?

Members of minority religions, with too few adherents to establish schools, may see injustice in the fact that only those belonging to more popular religions can use state money for religious education.

After all, who but Christians will be able to find a market for religious schools in rural Maine? This is a problem I have had with the conservative view of “religious freedom” all along: In practice, it only gives rights to conservative Christians — or, completely by accident, to other religious groups who happen to agree with conservative Christians on a particular issue like abortion or homosexuality.

So it may be amusing to imagine how this ruling might someday be used to make Evangelical taxpayers support a Muslim madrassah, or some other school they would abhor. But I question whether such a thing will ever happen. This Court’s sectarian majority believes in special rights for Christians. It will find ways around extending those rights to anyone else.

Here’s how Sherry Kolb put it in “Are Religious Abortions Protected?“, where she examines the argument (raised in a recent lawsuit filed by a Florida synagogue) that a Jewish doctor may feel religiously obligated to perform an abortion in situations where a state has banned them.

Despite appearances to the contrary, this Court is not especially friendly to Free Exercise claims. … Its rulings instead reflect its friendliness to conservative Christianity and, accordingly, to Judaism and Islam where the ask is minimal or the traditions happen to be the same. Christians can violate the anti-discrimination laws for religious reasons because they are Christians. The sooner we come to understand that the Court is all about Christianity rather than some capacious vision of religious liberty for all, the sooner we will begin the process of finding solutions to our modern-day theocracy problem that do not ask the Court to behave with integrity or consistency.

Comments

Boston Globe: The Supreme Court on Monday sided with a football coach from Washington state who sought to kneel and pray on the field after games. The court ruled 6-3 along ideological lines for the coach. The justices said the coach’s prayer was protected by the First Amendment.

Of course they did.

Jamal is not Ginni’s son

Damn. I guess I’ll have to edit.

BTW: Thank you. I should have said that first.

Thanks for the quick edit!

Can I recommend Siderea? she has been my go-to voice on the pandemic since before it started, and she has a clean, disciplined style I think would speak to you. Also a Bostonian – fwiw – so some geographical echoes. The piece she just published about the Civil War, and the possibilities of another civil war in the US had a fair amount of history I had never connected before: https://siderea.dreamwidth.org/1766175.html about how Southeners used the 3/5 compromise to basically buy or breed (unrepresented) bodies that counted towards the census and thus to their representation in Congress in order to gather additional political power to themselves and their states.

Trackbacks

[…] week’s featured posts are “Three Supreme Court decisions with long-term consequences” and “The January 6 hearings are accomplishing more than you […]

[…] For an amazing evaluation of latest Supreme Court docket rulings on abortion, weapons, and public funding of Christian faculties see Doug Mudar Ph.D. – “Three Supreme Court decisions with long-term consequences” […]

[…] Last week I covered three major Supreme Court decisions: the reversal of Roe, tossing out New York’s gun law, and forcing Maine to subsidize religious schools. All of them were major steps backwards for America, and are a big part of why this Independence Day feels so dismal. This week the march towards Gilead continued: a public school football coach can lead students in public prayer during a school event, and the EPA has lost a tool for fighting climate change. I’ve decided not to go into as much detail about these, and to cover them in the weekly summary. […]

[…] Last week I focused on three major decisions: overturning Roe, telling Maine it had to support religious schools (in certain circumstances), and tossing out New York’s gun law. Two more important decisions have happened since then: supporting a public-school football coach’s right to lead public prayers on the 50-yard line, and blocking the EPA from pushing utilities to shift away from coal-fired power plants. […]

[…] term, so the news is dominated by a flurry of controversial decisions. Last year the Court went out with a bang, eliminating abortion rights, striking down a century-old gun control law, and blowing a big hole […]

[…] this week, the final week of its annual term, the Supreme Court seemed to be backing away from the rogue behavior of last year, in which it had repeatedly ignored precedent, invented fanciful readings of history, and generally […]

[…] But we haven’t gotten to the craziest part yet: That result is a correct application of the doctrine Clarence Thomas laid out in the 2022 Bruen decision. […]

[…] attempt to understand what the law means. Recent Supreme Court decisions — like the Bruen gun control decision — have shaken that faith, to the point that law professors don’t know what to teach […]