The Supreme Court’s term ended last week.

But there’s still a lot of legal news to discuss.

When the final flurry of Supreme Court decisions came out late last week, you might have expected the legal world to go quiet for a while. Instead, this week

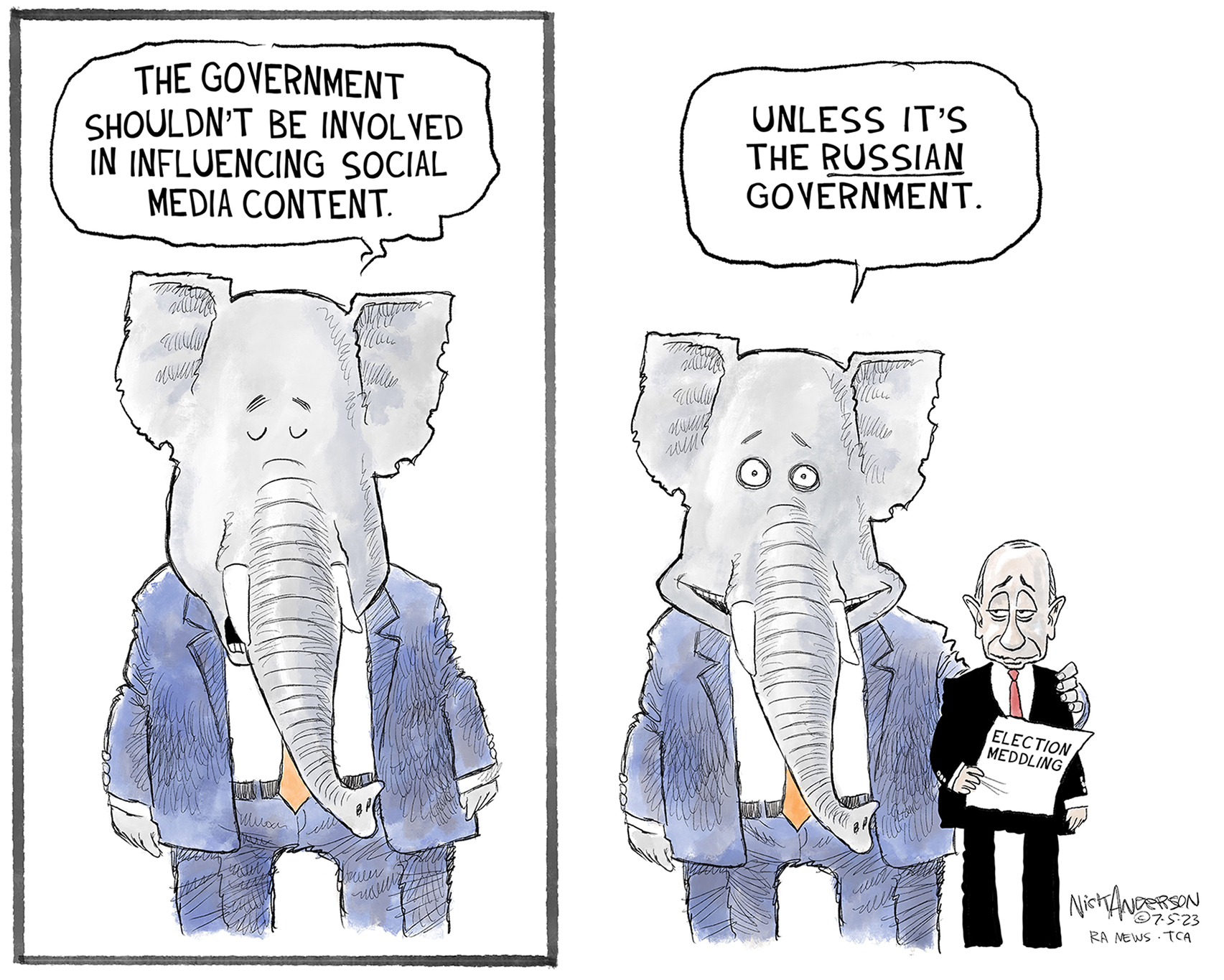

- A Trump-appointed judge took a long list of conservative conspiracy theories seriously, and issued an injunction banning large chunks of the executive branch from talking to social media companies. So if somebody puts on a lab coat and makes a YouTube claiming that the whooping cough vaccine turns kids into werewolves, the CDC has to sit on its hands.

- WaPo’s Ruth Marcus called attention to a ruling Federal District Court Judge Carlton Reeves of Mississippi made the previous week — a devastating attack on Clarence Thomas’ pro-gun ruling last year in Bruen. In a legal judo move, Reeves applied Bruen as written, ruling in favor of a convicted felon who claims the 1938 federal law barring him from owning guns is unconstitutional. Along the way, Reeves made it clear that he knows how ridiculous his ruling is, but he has to follow the Supreme Court’s lead.

- An appeals court overturned an injunction blocking Tennessee’s ban on gender-affirming care for minors. The law went into effect immediately.

Let’s take the three in one-by-one.

Opening the disinformation floodgates. On July 4, a date clearly chosen for its symbolic significance rather than because his court was open, US District Judge Terry Doughty of Louisiana, issued a 155-page memorandum justifying his injunction ordering large chunks of the Biden administration — the White House, State Department, FBI, CDC, et al — to have no contact with social media companies concerning disinformation.

The ruling makes dull reading, because it is mostly a rehash of claims made by the plaintiffs (the states of Louisiana and Missouri and several individuals) about “censorship” by the Biden administration. The judge appears not to have fact-checked at all, and most of the “violations” take the following form:

- Somebody posted a provably false claim on social media, containing dangerous misinformation about Covid or vaccines in general, or perhaps falsely attacking election officials in ways likely to provoke violence against them.

- Somebody in the government noticed, flagged the post for the platform the claim was posted on, and pointed out that the post violated the company’s own policies.

- The company took the post down, and may have sanctioned the poster’s account in some way.

In the examples given, the posters are almost all conservatives, for two simple reasons: The plaintiffs chose them that way, and conservatives post a lot more dangerous disinformation than liberals do.

This collection of examples has been spun into a conspiracy theory about the Biden administration’s sinister plot to silence conservative voices on the internet. The judge swallows this theory hook, line, and sinker, and responds accordingly.

The upshot of the injunction (if higher courts let it stand) is that if some video claims that vaccines could turn your child trans, the CDC just has to watch it go viral. Similarly, if a Russian troll farm starts a rumor among Black voters that they can vote over the internet, or that their mail-in ballots are fake and won’t be counted, the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) can’t do anything to stop the spread.

Given that I can’t recommend reading the judge’s memo itself, the best summary I’ve found is by Mike Masnick at TechDirt. What I like best about his account is that he gives the Devil his due: A few of the issues the judge raises are actually issues and should get public attention.

In particular, there is an issue with government pressuring private companies to do things that would be illegal for the government to do on its own. One form such pressure can take is threatening the companies with changes in the regulations that govern those companies.

There were some examples in the lawsuit that did seem likely to cross the line, including having officials in the White House complaining about certain tweets and even saying “wondering if we can get moving on the process of having it removed ASAP.” That’s definitely inappropriate. Most of the worst emails seemed to come from one guy, Rob Flaherty, the former “Director of Digital Strategy,”

However, most of the examples in the ruling are “made up fantasyland stuff”. And none were remotely as bad Ron DeSantis punishing Disney for speaking out against his Don’t Say Gay law, or Donald Trump threatening Amazon in order to pressure the Bezos-owned Washington Post to give him more favorable coverage. (Those examples are mine, not Masnick’s.)

Doughty seems incredibly willing to include perfectly reasonable conversations about how to respond to actually problematic content as “censorship” and “coercion,” despite there being little evidence of either in many cases … In doing so, Doughty often fails to distinguish perfectly reasonable speech by government actors that is not about suppressing speech, but rather debunking or countering false information — which is traditional counterspeech.

Masnick highlights the example of Dr. Fauci countering misinformation in the anti-lockdown Great Barrington Declaration, which Doughty frames as government censorship. Similarly, the influence of the CDC on social media companies is not an example of government coercion.

I mean, the conversation about the CDC is just bizarre. Whatever you think of the CDC, the details show that social media companies chose to rely on the CDC to try to understand what was accurate and what was not regarding Covid and Covid vaccines. That’s because a ton of information was flying back and forth and lots of it was inaccurate. As social media companies were hoping for a way to understand what was legit and what was not, it’s reasonable to ask an entity like the CDC what it thought.

Finally, he comes to the injunction itself, which has the kind of contradictory vagueness that characterizes so many conservative efforts (like anti-critical-race-theory laws). The injunction includes reasonable-sounding exceptions allowing communication about “criminal activity” or “national security threats” or “threats that threaten the public safety or security of the United States” and a few other things. However, most of the examples the judge casts as violations actually fall into one of his exceptional areas.

It seems abundantly clear that nearly all of the conversations were about legitimate information sharing, but nearly all of it is interpreted by the plaintiffs and the judge to be nefarious censorship. As such, the risk for anyone engaged in activities on the “not prohibited” list is that this judge will interpret them to be on the prohibited list.

So like Florida teachers, Biden-administration officials have no way to know what is legal and what isn’t. And so the injunction will have a chilling effect well beyond its text’s actually meaning.

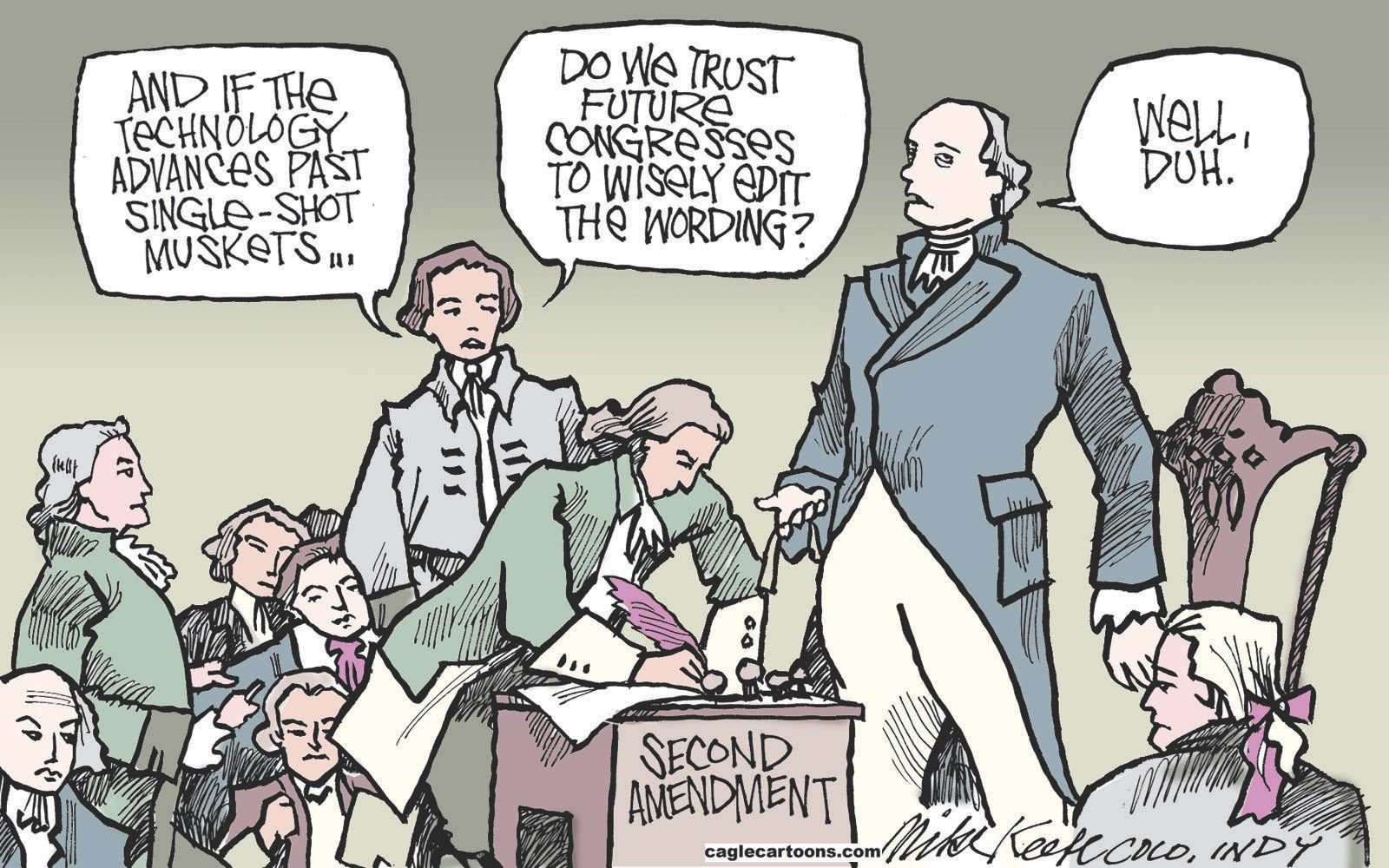

Protesting Bruen and originalism. Here’s Ruth Marcus’ summary of Judge Reeves’ ruling:

Lower-court judges are bound to follow the law as decreed by the Supreme Court. They aren’t bound to like it. And so, lost amid the end-of-term flurry at the high court, came another remarkable ruling by U.S. District Judge Carlton W. Reeves of Mississippi.

Reeves declared that the court’s interpretation of the Second Amendment compels the unfortunate conclusion that laws prohibiting felons from having guns violate the Second Amendment. He took a swipe at the conservative justices’ zealous protection of gun rights even as they diminish other constitutional guarantees. And, for good measure, he trashed originalism, now “the dominant mode of constitutional interpretation” of the Supreme Court’s conservative majority.

Reeves explained what forced his hand in making a ruling he clearly finds ridiculous:

Firearm restrictions are now presumptively unlawful unless the government can “demonstrate that the regulation is consistent with this Nation’s historical tradition of firearm regulation.” New York State Rifle & Pistol Ass’n, Inc. v. Bruen

In the case before him, a convicted felon caught with firearms was arguing that a 1938 law permanently banning felons from owning firearms violates his Second Amendment rights.

Reeves accepts the accuracy of the government’s claim that 120 post-Bruen federal court decisions have applied the law without noting such a violation. But …

In none of those cases did the government submit an expert report from a historian justifying felon disarmament. In none of those cases did the court possess an amicus brief from a historian. And in none of those cases did the court itself appoint an independent expert to help sift through the historical record.

Of course, Reeves has not done so either, but that’s OK, because neither did the Supreme Court in its gun-rights cases. Both Scalia in Heller and Thomas in Bruen relied instead on “law office history” that was “selected to “fit the needs of people looking for ammunition in their causes”. He summarizes the problem:

The federal felon‐in‐possession ban was enacted in 1938, not 1791 or 1868—the years the Second and Fourteenth Amendments were ratified. The government’s brief in this case does not identify a “well‐established and representative historical analogue” from either era supporting the categorical disarmament of tens of millions of Americans who seek to keep firearms in their home for self‐defense.

So “the government failed to meet its burden” in claiming that the law is constitutional.

Reeves’ ruling is worth bookmarking, because in contains an excellent history of the shifting interpretations of the Second Amendment. (Some years ago, I explained this difference of opinion by claiming that the Amendment doesn’t have any real meaning any more, so judges forced to interpret it have to make something up.)

But what’s really striking is Reeves’ closing section, which raises a question more people should be asking: Why doesn’t the Supreme Court defend all constitutional rights as zealously as it defends Second-Amendment rights?

In breathing new life into the Second Amendment, though, the Court has unintentionally revealed how it has suffocated other fundamental Constitutional rights. Americans are waiting for Heller and Bruen’s reasoning to reach the rest of the Constitution.

He starts with one obvious example: The Sixth Amendment guarantees all defendants a “speedy trial”. According to the historical record, what did the Founders consider “speedy”? Certainly not five years, which the Court endorsed in Barker v Wingo.

And then there are voting rights, which the Court has found to be “fundamental”, but it has erected much higher barriers to claiming that the government has violated your voting rights than it has set for violations of gun rights.

Maybe the Supreme Court is correct that in this country, to “secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity,” the government should have the burden of justifying itself when it deprives people of their constitutional rights. Perhaps the Court is also correct that constitutional rights should be defined expansively. The Court just isn’t consistent about it.

We have one Constitution. All of it is law. It has been enforced today as best as this Judge can discern the Bruen Court’s holding and reasoning. And, one hopes, a future Supreme Court will not rest until it honors the rest of the Constitution as zealously as it now interprets the Second Amendment.

Gender-affirming care. Fourteen states have passed laws banning gender-affirming care for minors. While the science justifying such treatments is far from settled, the majority of current medical opinion goes the other way. Also, by putting its own judgment above that of both doctors and parents, these red states expose the hollowness of the “parents rights” rhetoric they embrace in other contexts.

District court judges in Arkansas, Alabama, Florida, Indiana, Kentucky, and Tennessee have issued injunctions blocking these laws from taking effect. But Saturday was the first time an appellate court weighed in: A panel of Sixth Circuit judges ruled 2-1 to overturn the Tennessee injunction and let the law take effect. The Sixth Circuit also includes Kentucky, but this ruling does not directly effect Kentucky.

The ruling remains preliminary, as the 6th Circuit court plans to issue a full ruling by Sept. 30 after hearing arguments for a full appeal of the ban. In a filing Saturday, the court indicated it would decide the pending Kentucky case alongside Tennessee’s and set an accelerated schedule for briefing on those cases. However the schedule runs into next month and the next regularly scheduled argument session for the 6th Circuit after those deadlines is not until October.

Unless the other appellate courts follow the Sixth Circuit’s example, the issue is likely headed to the Supreme Court.

Comments

Not as urgent a matter as voting rights and speedy trials, but the Constitution is also specific on the topic of what we now call “intellectual property,” and notes that such monopolies can be granted for limited times for the purpose of advancing the useful arts. Our current patent, trademark, and copyright systems have gotten rather far afield of that, and it’s causing real long-term problems.

Blame Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg if you feel that way. She wrote the opinion in 2003’s Eldred v. Ashcroft that functionally write the “for limited terms” provision out of existence, which cleared the path to neuter of the Second Amendment’s well-regulated militia provision in gun cases.

That was just a chapter in a saga that’s been going on for 45 years now.

If I were made dictator for a day, a low-numbered order would revert copyright law to what it was in 1976, while also invalidating all US patents and shutting down the patent office until better procedures can be devised.

Trackbacks

[…] This week’s featured post is “Courts are still in session“. […]