If you have been paying attention to the current administration with any sense of skepticism at all, you probably worry about whether President Trump is a threat to American democracy as we have known it. Briefly:

- He repeatedly has tried to direct the Justice Department to target his enemies and to protect himself and his friends from investigation.

- He has dismantled traditions that protect the country against presidential corruption, refusing to release his tax returns or divest his business interests.

- He profits from his presidency.

- After campaigning to “drain the swamp”, he has instead tolerated a greatly increased level of corruption in his subordinates, such as Jared Kushner, Ivanka Trump, Scott Pruitt, Ben Carson, Ryan Zinke, and Steve Mnunchin.

- He has praised and defended the violence of his supporters.

- In addition to daily disparaging the free press, labeling as “fake news” any report he doesn’t like (including many that later prove to be true), he has attempted to intimidate The Washington Post by attacking the other business interests of its owner.

- On a daily basis, he lies to the American people in a manner more brazen and mean-spirited than any previous president.

- He has attacked the integrity of American elections, charging (without the slightest evidence) that millions of false votes were cast in 2016, all against him.

- He praises dictators, and insults America’s democratic allies, like the United Kingdom, Australia, France, and Germany.

- He defends white supremacists, fascists, and other anti-democratic groups that support him.

- His unconstitutional executive orders target marginalized religions and gender identities.

- Whether or not he actively conspired with the Russian government’s effort to make him president — the investigation into that issue has not yet produced a conclusion — he has consistently tried to distract the American people from the Russian attack on our democracy, to play down its implications, and to shield the Putin regime from consequences that might discourage it from launching similar attacks in future elections.

In January, as he marked the first complete year of the Trump administration, Benjamin Wittes characterized this as “banana-republic-type stuff” and commented

His aspirations are as profoundly undemocratic and hostile to the institutions of democratic governance as they have ever been. He announces as much in interview after interview, in tweet after tweet.

And yet, Wittes judged that during Trump’s first year, the response of the rest of the government was “ultimately encouraging”.

Trump simply cannot look back on the last year and be satisfied with the success of his war on the Deep State. His battle to remake it in his image has been largely unavailing—and has come at far greater cost to his presidency than to the institutions he is trying to undermine.

And that is very good news.

So how bad is it really? In other words, the rest of the government has largely remained true to American ideals, and has blocked Trump’s most authoritarian efforts. The courts remain independent, and have struck down several of his most egregious orders. The media has refused to be intimidated, and continues to hold him accountable. Law enforcement has largely — but not entirely — held steadfast against his encroachments on its integrity; so the Mueller investigation continues, and there have been no show trials of high-profile Trump enemies. The military has pushed back against his improper orders, and the intelligence services refuse to simply tell him what he wants to hear, help him subvert the justice system, or propagandize the American people. Even the Republican Congress, while often a lapdog, has occasionally growled: High-profile Republicans have protected Jeff Sessions, and threatened unspecified consequences if Robert Mueller is fired.

So how disturbed should we be? Is Trump simply a bad cold that American democracy will eventually throw off and return to good health? Or is his administration a cancer that our country might fight for a while, but will eventually succumb to? How do we even think rationally about such questions, rather than alternately give in to rosy denial or black despair as the mood strikes us?

Comparable challenges. If we were going to try to think about this like reasonable people, the first question to ask is: When have democracies faced challenges like this before? How did that go? How does our situation compare to theirs?

Trump, after all, is not the first demagogue with authoritarian tendencies to gain popularity in a democratic nation. Sometimes the fever passes, sometimes the nation falls into tyranny (Putin in Russia, Erdogan in Turkey), and some cases look bad but might still be salvageable (Orban in Hungary, Duda in Poland).

He’s not even the first American president to stress our democracy, or to be feared by the opposition as a rising dictator. Just about all our major wartime presidents fit that description: Much of what Lincoln did, including the Emancipation Proclamation, was constitutionally suspect, relying on implicit “war powers” that had never been precisely spelled out before. Wilson jailed Eugene Debs during the World War I, and approved the Palmer Raids against leftists in the postwar red scare. FDR broke the two-term tradition, tried to pack the Supreme Court with allies, and approved the Japanese internment.

We don’t usually think of those presidents as potential autocrats, because in each case subsequent administrations (sometimes under pressure from Congress) pulled back from autocracy, returning to what Wilson’s successor Harding called “normalcy“. Lincoln, Wilson, and Roosevelt all left American government changed, but in each case the expansion of executive power was eventually controlled, sometimes by codifying it in law and sometimes by setting new limits to keep it from happening again.

Nixon was another president who stretched and abused executive power. But he was forced to resign and voters gave the opposition party an overwhelming majority in Congress. Congress then passed the War Powers Act, wrote new campaign finance laws, and increased its oversight of the intelligence services. His presidency became a warning sign rather than a precedent; no subsequent president has justified his actions by claiming Nixon as his example.

So how does that all work? When does a democracy slide into dictatorship and when does it pull itself back from the brink? If that sounds like a major research project, you don’t have to take it on yourself: Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt already did in the recent book How Democracies Die. (If Ziblatt’s name is familiar, that might be because in December I tried to infer the lessons How Democracies Die makes explicit from his previous book, Conservative Parties and the Birth of Democracy.)

The importance of norms. Levitsky and Ziblatt’s first point is that the U. S. Constitution contains no magic formula that prevents democracy from failing here. Whatever “American exceptionalism” might mean, it doesn’t give us some kind of immunity from the diseases other democracies are prone to. Numerous countries have modeled their constitutions on ours, and seen democracy fail anyway.

Institutions alone are not enough to rein in elected autocrats. Constitutions must be defended — by political parties and organized citizens, but also by democratic norms. Without robust norms, constitutional checks and balances do not serve as the bulwarks of democracy we imagine them to be.

(Longtime Sift readers will recognize this as a theme I’ve been harping on for years in posts like “Countdown to Augustus” and “Tick, Tick, Tick … the Augustus Countdown Continues“.)

Much of our problem today predates the Trump administration, and stems from the fact that our norms have been sliding for decades. The Senate’s refusal to recognize President Obama’s appointment of Merrick Garland to the Supreme Court, or to respond to it with hearings and a vote, for example, was not explicitly unconstitutional, but was unheard of in all previous American history. Ditto for brinksmanship with the debt ceiling, or the decades-long evolution of the filibuster from a rarely used break-glass-in-case-of-emergency practice to an automatic tactic of minority obstruction. The other branches of government have changed their own norms to deal with Congress’ dysfunction: Presidents issue more sweeping executive orders (like Obama’s DACA), and the Supreme Court reinterprets mis-stated laws (like the Affordable Care Act) that it would once have sent back to Congress for correction.

If you go back to the bulleted list at the top of this post, you’ll notice that hardly any of my complaints about Trump are explicitly constitutional. The Constitution never says that the President can’t order the FBI to investigate the candidate he just defeated, that he can’t tell big whopping lies on a regular basis, or that he has to give the public enough information to judge whether or not he is corrupt. Those aren’t rules, they’re just good practices. That’s how we do things here in America.

Or how we used to do them.

The root norms. It would be easy to fill pages with the norms that Trump is breaking. Our system, for example, has a tradition of decorum. (“Will the distinguished gentleman from Oklahoma yield the floor for a question?”) No previous president has publicly talked about political rivals in such consistently belittling terms as Lyin’ Ted, Crooked Hillary, or Pocahontas.

But rather than list hundreds of specific norms, Levitsky and Ziblatt boil democracy’s essential norms down to two:

- mutual toleration, “the understanding that competing parties accept one another as legitimate rivals”

- forbearance, “the idea that politicians should exercise restraint in deploying their institutional prerogatives”

All the others stem from these. American government works well when the parties regard each other as rivals rather than enemies, and exercise their powers according to the Constitution’s underlying spirit, rather than wringing every conceivable advantage out of its words. Democracy is in trouble whenever one party regards the other as fundamentally treasonous, and then uses that opinion to justify pushing the powers of whatever offices it holds to their constitutional limits.

Much of what I’ve been doing in my “Augustus” series is chronicling the tit-for-tat loss of restraint between the parties. Most Americans have no appreciation of how far this could go, so I’ll provide an example: The 12th Amendment specifies that the sealed votes of the Electoral College are sent to the President of the Senate, who counts them “in the presence of the Senate and House of Representatives.” What if the President of the Senate, with the connivance of majorities in both houses, simply miscounted the votes and proclaimed someone else to be president?

There’s no provision for dealing with that scenario — and with innumerable similar situations — because the Founders never anticipated that our political leaders would go that far. And they wouldn’t. Or would they?

The 21st century road to dictatorship. The old model of democratic breakdown was the coup: Caesar illegally taking his army across the Rubicon, seizing Rome, and proclaiming himself Dictator for Life. That was the path of many 20th century dictators like Muammar Gaddafi in Libya or Saddam Hussein in Iraq. But 21st century autocrats have realized the usefulness of maintaining the trappings of democracy.

Vladimir Putin’s Russia, for example, still has elections, rival political parties, and dissident newspapers. Popular opposition leaders, however, have a way of finding themselves in prison or in exile or dead. Ditto for troublesome journalists. When the media empire of oligarch Boris Berezovsky became unreliable, he was forced to leave it behind him and flee the country. After a few years in exile, he was found hanged. When Mikhail Khodorkovsky, once the richest man in Russia, began financing dissident politicians, he went to prison.

It was all legal, of course. (Well, not the assassinations, but no investigator would dare trace them back to Putin.) The men who went to jail were convicted of real crimes (and maybe even committed some of them; it’s hard to reach the top of a corrupt system without breaking a law sometime). Similar stories could be told about Turkey or Hungary or Venezuela. The system resembles the quip variously attributed to either Mark Twain or Emma Goldman: “If voting could change anything, they’d make it illegal.”

Levitsky and Ziblatt use a soccer analogy to map out the steps by which an elected president becomes an autocrat:

- Capture the referees. In other words, get your people in charge of the judiciary, law enforcement, and intelligence, tax, and regulatory agencies. Anyone who used to be a neutral arbiter must become your partisan. You can do this in the judiciary, for example, by expanding the size of the Supreme Court and appointing your people to the new positions (as Roosevelt tried to do), or by impeaching judges who rule against you (as the Republican-controlled legislature is trying to do in Pennsylvania). (In North Carolina, the gerrymandered Republican majority in the legislature has done court-packing in reverse: It shrunk the size of the State Court of Appeals to prevent the new Democratic governor from filling the open seats.)

- Sideline star players on the other side. “Opposition politicians, business leaders who finance the opposition, major media outlets, and … religious or other cultural figures” are “sidelined, hobbled, or bribed into throwing the game.” With the referees already in your pocket, the carrots of government contracts and positions, or the sticks of ruinous regulations, taxes, and prosecutions can hollow out the institutions that otherwise might channel public opinion against you.

- Rewrite the rules in your favor. We were already seeing a lot of rule-rewriting on the state level prior to Trump: Gerrymandering and voter suppression have locked in large Republican majorities in states (like North Carolina) where the voters are more-or-less evenly split between the parties. In last November’s election in Virginia, Democratic candidates for the House of Delegates won the popular vote 53%-44%, but Republicans maintained a 51-49 majority. Combining a biased legal system with a lifetime ban on felon voting (as in Florida, where the Sentencing Project estimates that 20% of adult blacks can’t vote) can sideline a large chunk of the opposition electorate. In countries like Russia, field-tilting rules make it difficult for new parties to form, for genuine opposition candidates to get on the ballot, or for opposition voices to get their message out.

Once the right measures are in place, an aspiring autocrat doesn’t need the traditional trappings of tyranny — gulags, thought crimes, children informing on their parents, secret police breaking down doors in the middle of the night — to act with impunity and stay secure in his job.

Resistance. Unlike a coup, though, the subversion of a once-democratic system takes time. While you are corrupting some of the referees, suborning some opposition leaders, and rewriting some rules, the still-intact parts of the system can rise against you — if enough people recognize what is going on and transcend their previous differences. Putin, you may remember, did not become a dictator overnight.

Also, if a country is lucky — and I think the U.S. might have gotten “lucky” in this way with Trump — the would-be autocrat may not be particularly adept. Margaret Drabble’s metaphor of babies eating their mothers’ manuscripts might apply: “The damage was not, in fact, as great as it appeared at first sight to be, for babies, though persistent, are not thorough.” Trump may be persistent in his aggressions against democracy, but he lacks the discipline to be as effective as he otherwise might.

The rosy path. It’s easy to imagine that someday Trump will leave office peacefully — by choice or otherwise — and afterwards there will be a bipartisan effort to shore up the norms he violated.

Such a thing has happened before. For example, after FDR violated the unwritten rule that presidents should retire after two terms, Congress codified that limit in the 22nd Amendment. As a result, FDR’s four terms didn’t lead to a series of presidents-for-life. As I mentioned before, Nixon’s excesses led to a large Democratic majority in Congress that passed a number of executive-restraining laws.

Something similar could happen after Trump: Congress could mandate good practices that previously were taken for granted, forcing presidents to release their tax returns or hold their assets in blind trusts. Laws could spell out in detail which payments are constitutionally-banned “emoluments”. The wall separating the presidency from the investigative branches of the Justice Department could be strengthened.

Other changes wouldn’t require new laws: Voters could begin insisting again on virtues that Trump lacks, like experience, expertise, and honesty. They could once again value respectful and respectable behavior. Congress could begin taking its oversight role more seriously, rather than abusing or neglecting it depending on whether or not the presidency and Congress are controlled by the same party.

If that’s what happens, then the Trump administration will be like that time you drove home after a few drinks and arrived safely without incident. Yeah, it wasn’t a good idea and you shouldn’t make a habit of it, but ultimately no harm was done.

The dystopian possibility. So far, democracy has been protected by two main forces: The so-called “Deep State” (i.e., career government officials who are more committed to the missions of their organizations than to the orders they receive from the White House) and Trump’s overall unpopularity.

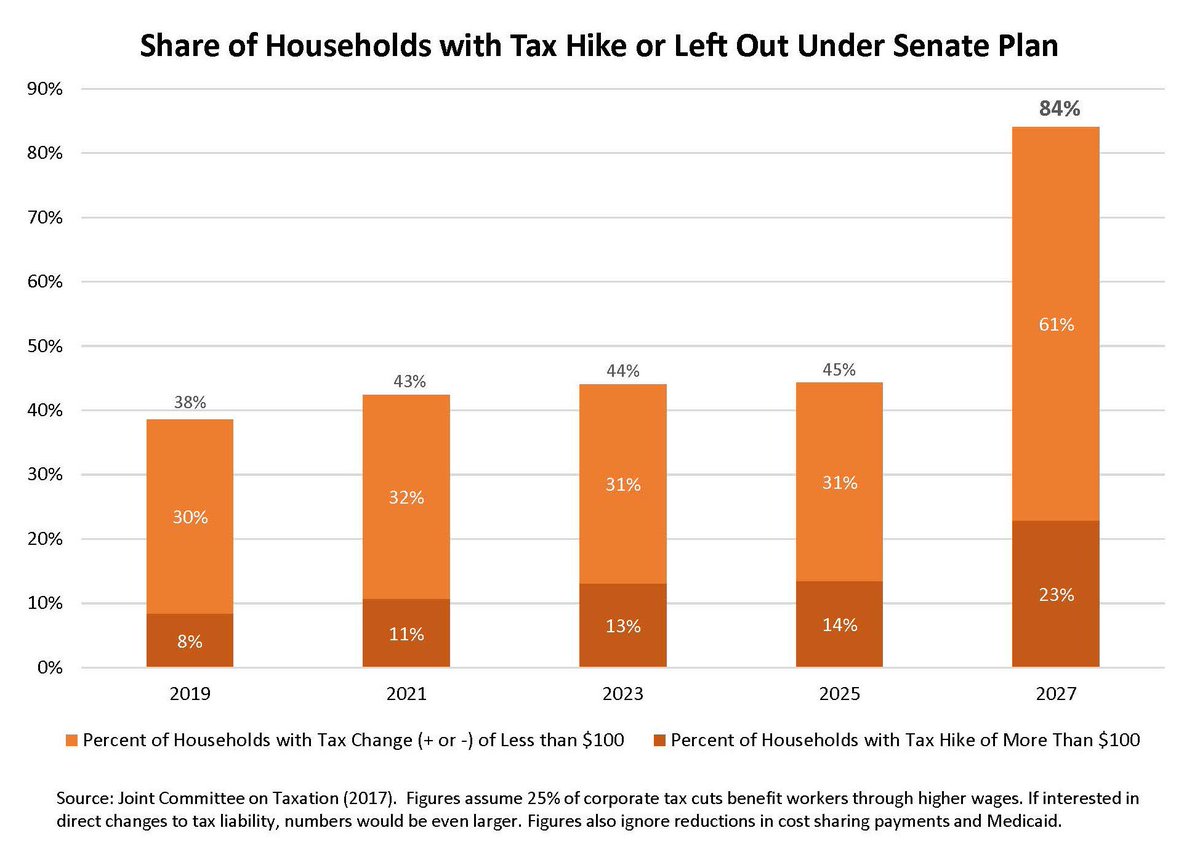

So, for example, career prosecutors — even if they are Republicans — have not been willing to sacrifice their integrity by manufacturing a case against Hillary Clinton, or ignoring evidence against Trump himself, just because he tweets that they should. Career EPA officials are refusing to become pawns of the fossil fuel industry no matter how much Scott Pruitt wants them to. Career economists at the Treasury didn’t concoct a bogus tax-cuts-pay-themselves analysis just because Steve Mnunchin promised they would.

That’s the Deep State in action: It’s not a conspiracy masterminded by some shadowy cabal. It’s the professional integrity of people who believe that their jobs mean more than just a paycheck or their bosses’ approval. (That’s true even in some cases where I disagree with them. I think a lot of CIA and Pentagon people really believe in America’s imperial mission, and in the disasters that will happen if they let down their guard. In their own minds, they are patriots.)

That’s both its strength and its weakness. You can’t kill the Deep State just by finding its leader and bribing, threatening, or imprisoning him or her. But conversely, it has no sense of strategy. It is made up of individuals, and individuals can be worn down. The Deep State has held its own for a little over a year, but can it hold for four years or eight?

If, God forbid, Trump got to replace one or two of the liberals on the Supreme Court, the courts might suddenly become pliable.

Trump’s unpopularity has shored up many institutions of democracy. The media has remained critical, rather than giving in the way it did to George W. Bush after 9-11. Republicans in Congress haven’t expressed much criticism, but they also haven’t cooperated with Trump’s desire to rewrite the rules. (The Senate keeps ignoring his plea to abolish the filibuster, and the idea of changing civil service laws to enable an executive-branch purge, or libel laws to muzzle the press, are non-starters.) Congressional Democrats have stayed unified rather than finding excuses to strike individual compromises. Federal judges have not been afraid to stick their necks out.

All that might change if Trump’s approval rating hovered around 60% rather than 40%, or if it were Democrats who were worrying about losing their jobs this fall rather than Republicans.

Levitsky and Ziblatt review cases where democracy held for a while, and then started to crumble, like Fujimori‘s Peru. It’s not hard to imagine how that could happen here: The predicted Democratic wave fails to materialize in the fall. The economy stays strong, the country avoids any new shooting wars or trade wars, and Trump’s victims — immigrants, Muslims, LGBT people, etc. — remain isolated. Much of the country then starts to say, “What was all that alarmism about?” When Jim Comey or Andrew McCabe winds up in jail, it seems like a one-off case rather than an assault on law enforcement.

Conversely, suppose Democrats overcome gerrymandering and regain control of the House. (It will take at least an 8% margin in the popular vote to do so.) Then laws will not change in Trump’s favor, Congress will investigate and expose excesses, and if Bob Mueller turns up evidence of impeachable offenses, the impeachment process will begin. We’ll be on our way to getting rid of Trump in 2020 (if not sooner), and starting to rebuild what has been torn down.

The crucial year, and the long-term challenge. Levitsky and Ziblatt don’t end with specific predictions, but my impression after reading their book is that 2018 is crucial. Neither complacency about American democracy’s resilience nor hopelessness about turning things around is warranted. The outcome is still undetermined.

In each party, there is a question: Will Democrats put aside their differences in the face of the larger threat, or will they let their factions be played off against each other? In the recent successful campaigns (Lamb in Pennsylvania, Jones in Alabama), they stayed united and won, but the divisions of 2016 are still not healed.

For Republicans, the question is whether their various factions will continue to let themselves be bought off — evangelicals by court appointments, business leaders by tax cuts and deregulation, and so on — or will enough of them come to understand what is really at stake? If they will not join the resistance, will they at least stay on the sidelines?

Long term, both parties need to figure out how to strengthen the norms of forbearance and tolerance, which were in trouble long before Trump arrived on the scene. Unless we can re-establish them, getting past Trump will not solve our problems. His failure, if it happens, might simply be a training example for new and better demagogues.