If we can’t trust ordinary people to be jurors, then we’ve already given up on Democracy.

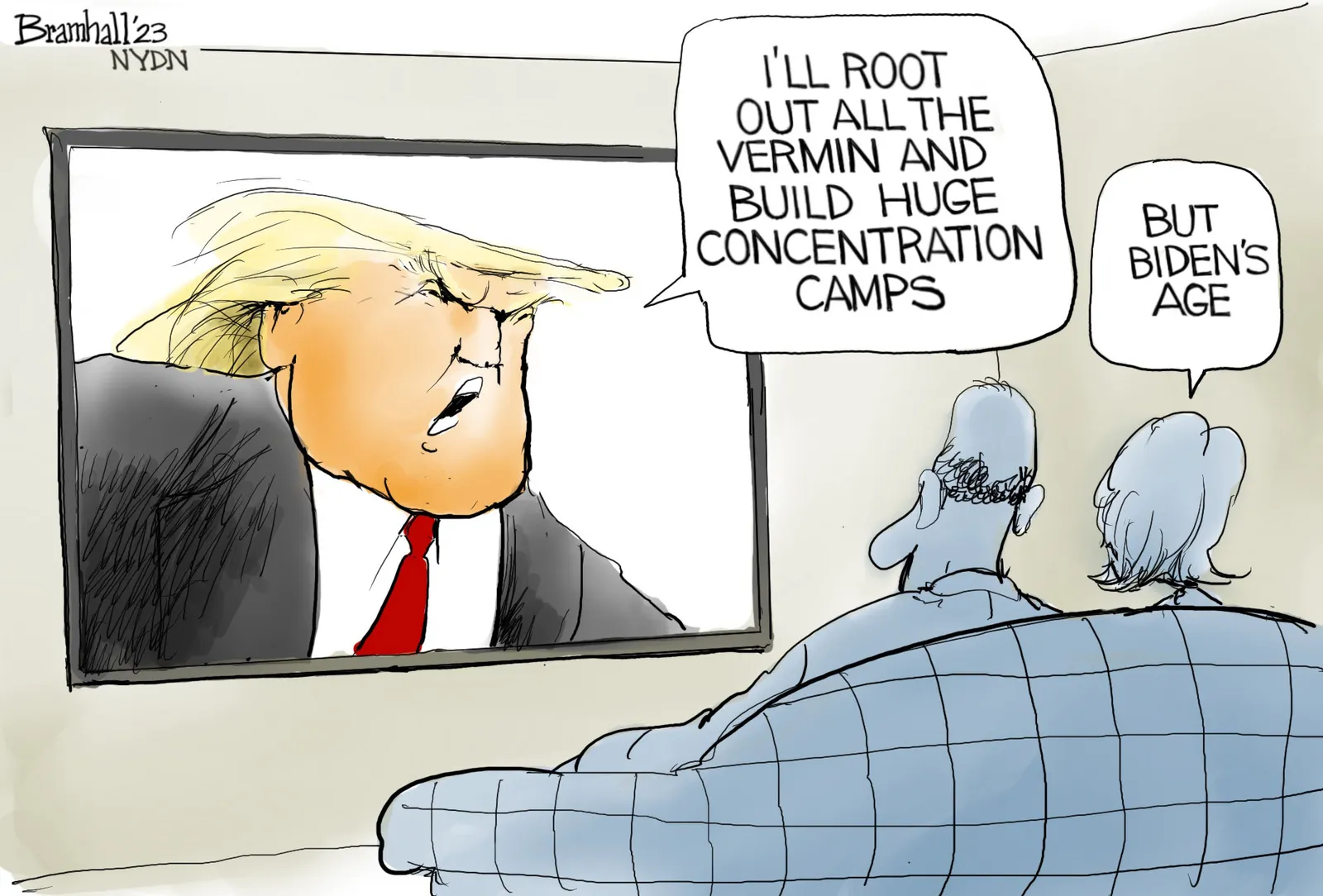

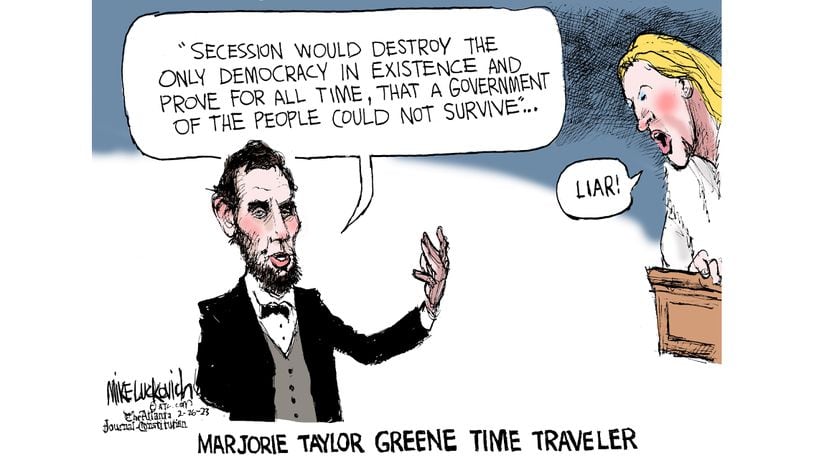

The central mission of a rising authoritarian movement is to destroy public trust in any institution that can stand in its way, and in particular, in any source of truth that is independent of the movement and its Leader. And so over the last few years the MAGA movement has told us that:

- We can’t trust our public health institutions to guide us through a pandemic.

- We can’t trust what climate scientists tell us about global warming.

- We can’t trust the FDA’s opinion on the safety of abortion drugs.

- We can’t trust historians to recount the story of American racism, or librarians to make sound decisions about books that discuss either race or sex.

- We can’t trust women who tell us they were sexually assaulted, or any women at all to make decisions about their own pregnancies.

- We can’t trust the news media to report simple facts (like the size of Trump’s inaugural crowd).

- We can’t trust our secretaries of state and local election officials to count votes.

- We can’t trust the FBI and the Department of Justice when they fail to find evidence of voting fraud.

- We can’t trust our intelligence agencies when they tell us about Trump’s friend Vladimir Putin.

- We can’t trust a judge of Mexican ancestry to oversee the Trump University fraud lawsuit, or any judges appointed by Democrats to handle Trump’s other trials.

And so on. Because in an authoritarian system, the Leader defines Truth. Only he can be trusted.

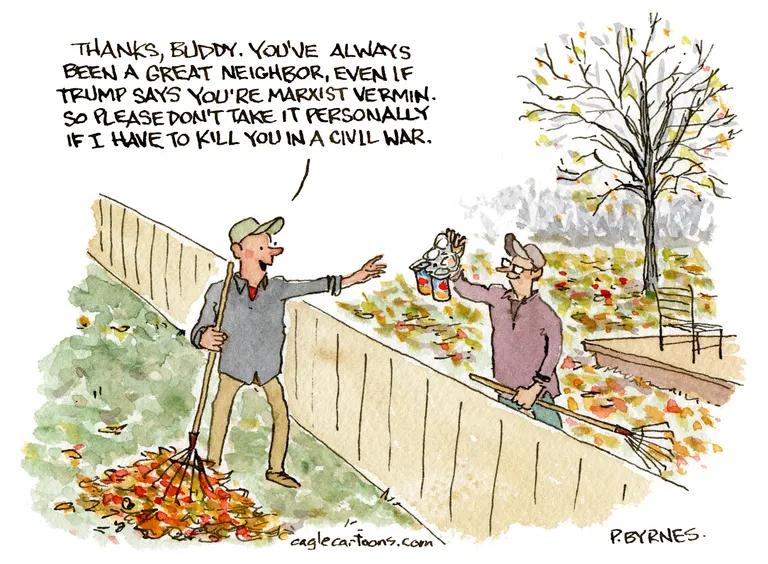

In each of these situations, we are presented with a Manichean choice: There is MAGA and there is the Deep State. There are Trump followers and Trump haters. If you are not one, you are the other — and that’s all that matters. No one can be trusted to simply do their job in a fact-based, objective, or professional manner.

This week we saw another example of that authoritarian trust-destroying mission: We can’t trust juries. Specifically, we can’t trust a jury of New Yorkers — or any jury convened in a blue state — to stand in judgment over the Great Leader himself. Most New Yorkers didn’t vote for Trump, and so by definition they are Trump haters who are incapable of listening to evidence and forming objective opinions about his guilt or innocence.

Already in August, Kellyanne (alternative facts) Conway was telling Fox News that Trump couldn’t get a fair trial in three of the four venues where he has been indicted — “the most liberal county in Georgia, D.C., New York City, all these places that voted against him”. Apparently only in south Florida, under the supervision of a judge he appointed himself, could Trump possibly get a fair shake. Because a courtroom is just another political arena where all that matters is the love or hate you feel for Donald Trump.

It’s important to push back on this insidious belief, because it strikes at the heart of any notion of Democracy. If ordinary people can’t be trusted, then they can’t be allowed to govern themselves. If they are too unreliable to be jurors, why should these same untrustworthy people be allowed to vote or protest or express themselves in any way at all? If ordinary people can only be trusted when they belong to the Leader’s party, then why let any other party compete for power?

There’s a reason that trial by jury goes back to the Magna Carta, and was guaranteed by the Founders in the Sixth Amendment. A belief in juries is fundamental to the whole project of Democracy.

Encouraging corruption. Once you convince yourself that an institution is inherently corrupt, the obvious next step is to make that corruption work for you rather than against you. So conservative talk-radio host Clay Travis made this plea to his listeners:

If you’re a Trump supporter in New York City who is a part of the jury pool, do everything you can to get seated on the jury and then refuse to convict as a matter of principle, dooming the case via hung jury. It’s the most patriotic thing you could possibly do.

In other words: Don’t answer the judge’s questions honestly, and once you get on the jury, don’t do your job with integrity. Don’t listen to the evidence and form an objective opinion. Refuse to convict “as a matter of principle”.

What principle would that be? That the Leader can do no wrong? That he is above the Law?

Rep. Byron Donalds (who a few months ago was in the running to be Speaker of the House) similarly denied that there was any need for jurors to listen to the prosecution’s case:

My plea is to the people of Manhattan that may sit on this trial: Please do the right thing for this country. Everybody’s allowed to have their political viewpoints, but the law is supposed to be blind and no respecter of persons. This is a trash case; there is no crime here; and if there is any potential for a verdict, they should vote not guilty.

But of course, there is a crime: falsification of business records, which is illegal in New York. Donalds knows this, just as he knows that Michael Cohen has already served time for his role in this illegal plot. If he truly believed Trump to be innocent, he could simply urge jurors to do their jobs with integrity, and express faith in the outcome. But he didn’t, did he?

Fox News has been doing its best to out the jurors, so that they can be vulnerable to intimidation and coercion from the violent MAGA faithful. In one case they have already succeeded: A juror who was seated on Tuesday came back Thursday asking to be excused because people had already begun to guess her identity. Fox host Jesse Watters had picked her out (by number) as a juror who might be difficult for Trump. (The evidence against her? She had blasphemed by saying: “No one is above the law.”) He then slandered (and Trump retweeted him) the jurors in general.

They are catching undercover Liberal Activists lying to the Judge in order to get on the Trump Jury.

In reality, Trump’s lawyers had caught people with liberal views saying that they could be objective. There is no reason to believe they can’t, beyond the dogma that all liberals are irrational Trump-haters.

In the face of this attack on a core democratic value, it’s important to reaffirm our faith in it, as Vox’ Abdallah Fayyad does:

Regardless of what the former president says, the demographics of New York or Washington, DC, won’t determine whether or not he will receive a fair trial. That will depend on how the prosecution makes its case, and whether the jurors will take their jobs seriously and evaluate the case on its merits rather than on their views of the defendant — something that juries are more than capable of doing.

That’s why Trump’s disingenuous attacks on the jury are dangerous: not because he’s questioning their potential fairness (juries can indeed be unfair, and defendants have the right to point that out), but because he’s broadly deeming some Americans — that is, anyone who doesn’t support him — as inherently illegitimate jurors.

If you believe in Democracy, the legitimacy of jurors doesn’t depend on who they voted for in 2020 or plan to vote for later this year or what they think of Donald Trump. Trials are not popularity contests. You can believe Trump is the scum of the Earth, and still evaluate fairly whether the prosecution has proved its case against him. As many a defense lawyer points out in summation: “You don’t have to like my client to find him not guilty.”

Could I be a juror? As I watched (from a distance) the Manhattan court’s effort to form a Trump jury, I did what I think a lot of people did: wondered how I would answer the questions prospective jurors were asked. In particular: Could I be objective? Could I listen to the evidence and arguments from both sides and reach a fair verdict?

I decided that I could. Now, as anyone who reads this blog or follows me on social media knows, I have a very strong negative opinion of Donald Trump. I have openly said that I think he’s guilty, not just in this case but in the other three cases as well. Had I been in that courtroom, the defense would undoubtedly have used one of their peremptory challenges to make sure I never came anywhere near the jury box. So how could I imagine being a fair juror?

Here’s how: I have a clear sense of the duties of a juror takes on. And the principle of trial by jury is more important to me than the fate of one man. Demagogues and grifters like Trump will come and go in American history, but trial by jury is something that I hope will endure through the centuries. I wouldn’t want to be part of screwing it up.

In particular, I believe that everyone accused of a crime deserves a fair trial, and that the prosecution has a responsibility to prove its case beyond a reasonable doubt. I also believe in the rules of evidence. As a juror, it wouldn’t matter to me what I had read in the news media or what I thought I remembered from the internet: The real evidence, the trustworthy evidence, isn’t what I heard on Fox News or MSNBC, it’s the evidence that shows up in court. And so when the trial ground to its conclusion, I would ask myself: Given what I’ve heard in court, has the prosecution proved its case? If it hadn’t, I would vote to acquit.

Now, I sincerely doubt that anything that might happen in this trial will change my opinion of Trump. At the end of the trial, I’m sure I will still believe he’s a fundamentally dishonest man who cares for no one but himself. I may even still believe that he’s guilty of the charges against him.

But if I’m a juror, that doesn’t matter. The question isn’t “Do you believe he’s guilty?” but “Has the prosecution proved he’s guilty.” If they haven’t, I could vote to acquit — even as I continued to hope that the prosecutors in one of his other cases would have more success.

Can this jury be fair? I have great faith that it can.

Part of my faith comes from having served on a jury several years ago in an emotionally fraught federal drug case. The defendant came from a household that in many ways exemplified the American dream: He and his wife were Hispanics who had worked their way into the middle class and were raising several children, all younger than 10. He worked in a local factory, and she was a nurse. The real bad guy here seemed to be the defendant’s brother, a career drug dealer that the government had been failing to make a case against. He sold drugs out of the defendant’s basement, and when the undercover cop showed up wanting to buy, he was too smart to sell. But the defendant trusted the cop, so the brother in essence said, “If you trust him, you sell to him.” The defendant did, and that was how he came to be on trial.

After the evidence was presented, we deliberated for an afternoon and most of the next morning. We were all over the map, and I had a very difficult night while I shouldered my responsibility. All of us sympathized with the wife and children. Several jurors who had been leaning not-guilty in the afternoon changed their minds overnight: By morning they were angry at the defendant for letting his brother sell drugs out of the house where his kids lived.

In the end, we answered the question we were given: Had the government proved that he sold the drugs? It had, and we convicted him. (We also had a meeting with the judge where we pleaded for him to sentence mercifully. I never checked whether he did.)

I learned a few things from this experience: First, the ritual of the court is powerful magic. You may come in with all sorts of impressions and opinions. But you very quickly learn to appreciate the awesomeness of the power you have been delegated and the responsibility it puts on you. (Spider-Man is right: With great power comes great responsibility.)

Second, no matter how different the individuals are, some kind of group loyalty develops. Not reaching a verdict feels like failure, and the jury doesn’t want to fail. We had each given a week of our time to this trial, and we didn’t want to believe our time had been wasted.

This is why I have faith in the Trump jury. Yes I can imagine all sorts of scenarios where somebody follows Clay Travis’ instructions: lies to the court so that they can get on the jury and rig the outcome. But that’s a harder mission to pull off than you might think.

My jury only met for a week. This one will probably sit for a month or more. During that time, they’ll share a lot of cups of coffee and more than a few lunches. They’re not supposed to discuss the trial until deliberation, but they’ll undoubtedly find other things to talk about: kids, jobs, the weather, TV shows. They’re going to see each other as people and develop a sense of common purpose.

Imagine spending that whole month with people while animated by a single malevolent thought: “I’m going to make sure you all fail. Because of me, this month we’ve all sacrificed will come to nothing.”

That would be a hard mission to carry out.

Even if you came onto the jury with a fairly strong belief in Trump, I think the ritual of the court and the camaraderie of the jury might well capture you. Every day you will look at Trump and realize that he is (as one prospective juror put it) “just a guy”, and not the great savior you imagined him to be. You will see him glower and bluster and doze off and treat you and your fellow jurors and the judge with disrespect. You will hear the prosecution witnesses assemble the case against him step by step. (You will have heard that the case is all politics, but in fact no one is talking politics. They’re presenting evidence.) When the defense takes its turn, you will hope for some grand revelation that shatters the prosecution’s case. And you will be disappointed.

During deliberation, you will have no real argument to make against your fellow jurors who want to convict. Over the month, you will have learned that they are not the frothing Trump-haters Fox News led you to expect. They’re just ordinary people trying to do their civic duty. Are you then going to look them all in the eye and admit that out of sheer stubbornness, you are going to make them fail?

Maybe. But I doubt it.

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/69965216/8349514053_afdd89e0b8_o.0.jpg)