Six things ordinary people can do to restore sanity.

One of the most difficult experiences of democracy is to watch your country going crazy, and feel responsible. In a dictatorship you could just zone out: The Powers That Be will do what they do, and your opinion doesn’t matter anyway. Your neighbors, your friends, your co-workers — their opinions don’t matter either, so there’s no point in arguing with them, or even letting them know you disagree. You might as well just binge-watch something light on TV, and wait for the wave to pass.

In a democracy it’s different: We are the wave. Politicians really do respond to certain kinds of public opinion, sometimes to our shame. So, for example, my Democratic governor (Maggie Hassan of New Hampshire, who I have voted for, given money to, and was planning to support for the Senate) called for a halt on admitting Syrian refugees. (She later reduced it to a “pause“, “until intelligence and defense officials can assure that the process for vetting all refugees is as strong as possible to ensure public safety.” But the damage was done: Any governor who wants to come out against refugees can claim bipartisan support.) My representative (Annie Kuster of NH-2, who I have also voted for and given money to) voted Yes on the American Security Against Foreign Enemies Act, which at a minimum would delay any new refugee resettlements by 2 or 3 months, and might snafu the process altogether. [1] (Check your representative’s vote here.)

In a democracy it’s different: We are the wave. Politicians really do respond to certain kinds of public opinion, sometimes to our shame. So, for example, my Democratic governor (Maggie Hassan of New Hampshire, who I have voted for, given money to, and was planning to support for the Senate) called for a halt on admitting Syrian refugees. (She later reduced it to a “pause“, “until intelligence and defense officials can assure that the process for vetting all refugees is as strong as possible to ensure public safety.” But the damage was done: Any governor who wants to come out against refugees can claim bipartisan support.) My representative (Annie Kuster of NH-2, who I have also voted for and given money to) voted Yes on the American Security Against Foreign Enemies Act, which at a minimum would delay any new refugee resettlements by 2 or 3 months, and might snafu the process altogether. [1] (Check your representative’s vote here.)

If my side has been characterized by politicians timidly letting the panic sweep them away, on the other side it’s been bedlam. Ben Carson is openly dehumanizing refugees with metaphors about “rabid dogs”. Donald Trump is talking about closing mosques, because “we’re going to have no choice”. He has advocated forcing American Muslims to register with the government, so that they can be tracked in a database. Marco Rubio expanded Trump’s proposal to call for shutting down “anyplace where radicals are being inspired”. Ted Cruz and Jeb Bush want a religious test for refugees: We should accept Christians, but not Muslims. John Kasich wants to create a government agency to promote “Judeo-Christian values” around the world. [2]

Chris Christie says we shouldn’t even let in little kids. Like, say, this Syrian girl, who mistook the photographer’s camera for a gun and tried to surrender.

And remember this Syrian boy? His photo evoked international compassion a couple months ago, but that never lasts, does it?

And remember this Syrian boy? His photo evoked international compassion a couple months ago, but that never lasts, does it?

When Governor Jay Nixon didn’t try to block Syrian refugees, state Rep. Mike Moon called for a special session of the legislature to stop “the potential Islamization of Missouri“. But the bull goose loony (to borrow Ken Kesey’s phrase) was a Democrat: Roanoke Mayor David Bowers, who justified his refusal to cooperate with resettling refugees by citing FDR’s Japanese internment camps during World War II. That national disgrace is now a precedent. (Who knows? Maybe slavery or the Native American genocide will become precedents too.)

I had never heard of Rep. Moon or Mayor Bowers before, but none of the Republican presidential candidates seemed this insane when they started campaigning. So I suspect they’re just saying what they think will appeal to their voters. They may be pandering to the public fear, attempting to benefit from it, and playing their role in spreading it, but they didn’t start it.

We did that. Ordinary people like us. Our friends, our relatives, our co-workers, the people we know through social media. And so I suspect it’s up to us to stop it.

I have to confess I didn’t see this coming. After the Paris attacks, I expected a push to hit ISIS harder, maybe even to re-invade Iraq and add Syria to the occupation zone. (Jeb Bush recently joined Ben Carson, John Kasich, and Lindsey Graham in calling for ground troops, though he was vague about how many.) I didn’t foresee an Ebola-level panic [3] focused on the refugees who are running from the same people we want to fight, much less the yellow-starring of American citizens who practice an unpopular religion.

But OK, here we are. Our country is going crazy and we are right in the middle of it. What do we do now?

1. Don’t make it worse. In particular, don’t be the guy hysterically running around and yelling at other people not to panic. Sanity begins within. You have to find it in yourself before you can transmit it to other people.

So: calm down. If you need help, seek out other calm voices. The needed attitude is a firm determination to slow this panic down, not a mad urge to turn the mob around and run it in the opposite direction.

Once you start to feel that determination, you’re ready to engage: Participate in conversations (both face-to-face and in social media). Write letters to the editor. Write to your representatives in government.

Don’t yell. Don’t humiliate. Just spread calm, facts, and rationality. When engagement starts to make you crazy, back away. Calm down again. Repeat.

2. Disrupt the spread of rumors. Panics feed on fantasies and rumors. Fantasies tell people that horrible things could happen. Rumors assert that they already are happening.

Social media is the ideal rumor-spreading medium, so it takes a lot of us to slow a rumor down. But you don’t have to be a rhetorical genius to play your part. Simple comments like “I don’t think this is real” or “That’s been debunked” are often sufficient, especially if you have the right link to somebody who has checked it out. The debunking site Snopes.com has tags devoted to Paris attack claims and Syrian refugees.

Here are a couple of the false rumors I’ve run into lately:

Current Syrian refugees resettled in America are not “missing”. I heard this one during a Trump interview with Sean Hannity. Trump refers to “people” who are missing — with the implication that they have gone off the grid and joined some kind of underground. Hannity corrected to “one person … in New Orleans”. (Think about that: It’s gotten so bad that Sean Hannity has to tone stuff down.) But Catholic Charities has debunked that story: They resettled the guy in Louisiana, and then he moved. He’s not missing. (The source of this rumor was probably the desperate David Vitter campaign for governor, which tried to ride the refugee panic to a comeback victory. It didn’t work.)

No, lying to further the cause of Islam is not a thing. Under the doctrine of taqiya, a Muslim may lie about his faith to escape serious persecution or death. Anti-Muslim propagandists have tried to turn this into a sweeping principle that justifies any lie to an unbeliever — and consequently justifies non-Muslims in disbelieving anything Muslims say. But it doesn’t work that way. Now, I’m sure ISIS has undercover operatives (just like we do) and that Muslim leaders lie (just like leaders of other faiths). But there’s no special reason to think Muslims are less truthful than the rest of us.

I won’t try to predict what further rumors will arise. But when you run into one, check Snopes, google around a little, and see if somebody has already done the hard work of checking it out.

As you participate, remember: In social media, you’re not just talking to the person you’re responding to (who might be hopeless), you’re also talking to his or her friends. Some of those friends might have been ready to like or share the rumor until they saw your debunking comment. You’ll never know who they are, but their hesitation is your accomplishment.

3. Make fantasies confront reality. Fearful fantasies work best when they’re vague and open-ended. For example: Terrorists are going to sneak in as refugees and kill us!

Think about that: A terrorist is going to submit to a one-or-two-year screening process, establish a life in this country, and then drop off the grid, strap on a suicide vest, and blow himself up in some crowded place.

Does that scenario make any sense? Wouldn’t it be simpler to come as a tourist? An aspiring terrorist could get in much faster with less scrutiny, spend a few weeks visiting Disney World or hiking the Grand Canyon, and then start killing us, while his fake-refugee brothers-in-arms are still tangled in red tape.

Sometimes the most devastating response to a nightmare fantasy is the simple question: “How does that work, exactly?” If you can get a person to admit “I don’t know”, you’ve restored a little sanity to the world.

4. Call out distractions. The Slacktivist blog makes this point so well that I barely need to elaborate.

As a general rule with very few exceptions, whenever you encounter someone arguing that “We [America] shouldn’t be doing X to help those people over there until we fix Y over here for our own people,” then you have also just encountered someone who doesn’t really give a flying fig about actually doing anything to fix Y over here.

So if somebody says we shouldn’t be taking in Syrian refugees while there are still homeless children or veterans or whatever in this country, the right response is to ask what they’re currently doing to help the people they say are more deserving. Odds are: nothing. Their interest in homeless American vets begins and ends with the vets’ value as a distraction from helping refugees.

Once you grasp this tactic, you’ll see it everywhere. So: “All those resources you want to devote to fighting climate change would be better spent helping the poor.” “OK, then, what’s your plan for using those resources to help the poor? Can I count on your vote when that comes up?” Silence.

When people argue that there’s a limited amount of good in the world, so we shouldn’t waste it on anybody but the most deserving, ultimately they’re going to end up arguing that they should keep the limited amount of good they have, and not use it help anybody but themselves.

5. Make sensible points. If you can capture somebody’s attention long enough to make a point of your own, try to teach them something true, rather than just mirror the kind of bile they’re spreading. This is far from a complete list, but in case you’re stuck I have a few sensible points to suggest:

The process for vetting refugees is already serious. Time explains it here, and Vox has an actual refugee’s account of how she got here.

America needs mosques. Research on terrorism (not to mention common sense) tells us that the people to worry about aren’t the ones who are pillars of their communities. The young men most likely to become terrorists are not those who feel at home in their local houses of worship, but the loners, or the ones have only a handful of equally alienated friends. (That’s not just true for Muslims like the Tsarnaev brothers, but also white Christian terrorists like Dylann Roof.) When you can’t connect face-to-face, that’s when you start looking around online for other radical outcasts you can identify with.

So it would be bad if American mosques just magically went away, as if they had never existed. But it would be infinitely worse for the government to start closing them. What could be more alienating to precisely the young men that ISIS wants to recruit?

Religious institutions aide assimilation. Imagine what would have happened if we had closed Italian Catholic churches to fight the Mafia, or Irish Catholic churches for fear of the IRA, or Southern Baptist churches that had too many KKK members.

The Founders envisioned American religious freedom extending to Muslims. As Ben Franklin wrote:

Even if the Mufti of Constantinople were to send a missionary to preach Mohammedanism to us, he would find a pulpit at his service.

We seldom look back with pride on decisions made in a panic. This is where the Japanese internment precedent should be quoted: That’s the kind of stuff we do when we get caught up in a wave of fear and anger. So should our refusal to take in Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany. The Red Scare is another precedent. More recently: Everybody who jumped from 9-11 to “Invade Iraq!” or “We need to torture people!” — are you proud of that now?

6. Look for unlikely allies, and quote them. Listening to Trump, Cruz, and the rest, it’s easy to imagine that everybody in the conservative base is part of the problem. But that’s not true. Here are a few places you may not realize you have allies.

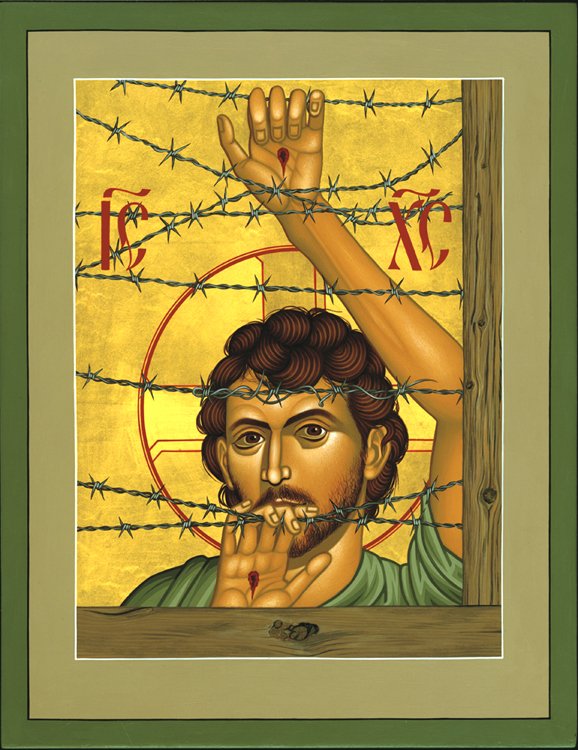

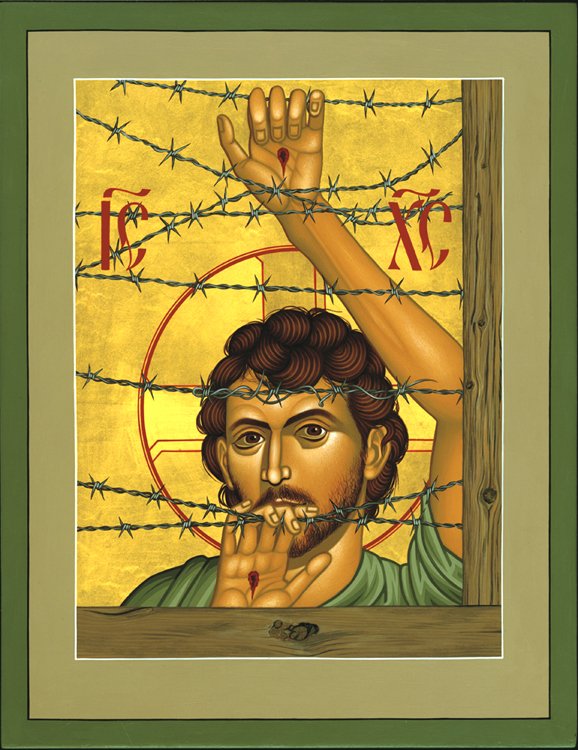

Christians. I know: The self-serving Christians [4] so dominate the public conversation that sometimes it’s hard to remember the existence of actual American Christians, i.e., people trying to shape their lives around the example and teachings of Jesus. But if you screen out the clamor of “Christians” focused on the competition between their tribe and the rival tribe of Muslims, you will hear people who are trying to figure out what the Good Samaritan would do.

Christians. I know: The self-serving Christians [4] so dominate the public conversation that sometimes it’s hard to remember the existence of actual American Christians, i.e., people trying to shape their lives around the example and teachings of Jesus. But if you screen out the clamor of “Christians” focused on the competition between their tribe and the rival tribe of Muslims, you will hear people who are trying to figure out what the Good Samaritan would do.

And I’m not just talking about liberal Christians from the mainstream sects. Lots of evangelical Christian churches have been involved in resettling refugees in their local areas. They know exactly how bad it is for refugees, and can put faces on the issue. They’re not happy with the people who are trying to demonize Jamaal and Abeela and their three kids.

The Mormon community retains its collective memory of being outcasts. [5] So Utah stands out as a red state whose governor has not rejected settling Syrian refugees.

Ryan Dueck sums up:

as Christians, there are certain things that we just don’t get to do.

We don’t get to hunt around for excuses for why we don’t need to include “those people” in the category of “neighbour.”

We don’t get to look for justifications for why it’s better to build a wall than open a door.

We don’t get to label people in convenient and self-serving ways in order to convince ourselves that we don’t have to care for them.

We don’t get to speak and act as if fear is a more pragmatic and useful response than love.

We don’t get to complain that other people aren’t doing the things that we don’t want to do.

We don’t get to reduce the gospel of peace and life and hope to a business-as-usual kind of political pragmatism with a bit of individual salvation on top.

We don’t get to ask, as our default question, “How can I protect myself and my way of life?” but “How does the love of Christ constrain and liberate me in this particular situation?”

And all of this is, of course, for the simple reason that as Christians, we are convinced that ultimately evil is not overcome by greater force or mightier weapons or higher walls or more entrenched divisions between “good people” and “bad people,” but by costly, self-sacrificial love. The kind of love that God displayed for his friends and his enemies on a Roman cross.

If you read the comments on that post, or look at this rejoinder from National Review, you’ll see that Dueck’s point of view is not universal among people who think of themselves as Christians. But it’s out there.

Libertarians. Some parts of the libertarian right understand that oppression is unlikely to stop with Muslims. So Wednesday the Cato Institute posted its analysis: “Syrian Refugees Don’t Pose a Serious Security Threat“. Conservatives who won’t believe you or Mother Jones might take Cato more seriously.

Scattered Republican politicans. I don’t want to exaggerate this, but here’s at least one Republican trying to slow the hysteria down: Oklahoma Congressman Steve Russell. He said this on the floor of the House:

America protects her liberty and defends her shores not by punishing those who would be free. She does it by guarding liberty with her life. Americans need to sacrifice and wake up. We must not become them. They win if we give up who we are and even more-so without a fight.

Russell eventually knuckled under to the pressure and voted for the SAFE Act, but says that he got something in return from the Republican leadership: the promise of a seat at the table in the subsequent negotiations with the Senate and the White House. We’ll see if that makes a difference.

These next few days, I think it’s particularly important for sensible people to make their voices heard, and to stand up for the courageous American values that make us proud, rather than the fear and paranoia that quake at the sight of orphan children.

Every time you stick your neck out — even just a little — you make it easier for your neighbor to do the same. Little by little, one person at a time, we can turn this around.

[1] What disturbs me most about the supporters of the SAFE Act is that they’re not calling for any specific changes in the way refugees are screened, they just want more of it. I suspect most of the congresspeople who voted for the act have no idea how refugees are vetted now, much less an idea for improving that process.

As we have seen in the discussion of border security, more is one of those desires that can never be satisfied. If this becomes law and in 2-3 months the administration comes out with its new refugee-screening process, we will once again face the cries of “More!”, along with the same nightmare fantasies about killer refugees.

[2] Actually, the main thing wrong with Kasich’s proposal is that he sticks an inappropriate religious label on the values he wants to promote: “the values of human rights, the values of democracy, freedom of speech, freedom of religion, and freedom of association.” Russian dissident (and former chess champion) Garry Kasparov has a better term for these: modern values.

In the West, these values were championed by Enlightenment philosophers, many of whom were denounced as heretics and atheists by the Christian and Jewish authorities of their era. So no, these are not Judeo-Christian values.

[3] The two panics have a number of similarities, as John McQuaid points out. In each case “a terrifying and poorly-understood risk has stirred up apocalyptic fantasies and brought out the worst in the political system.”

If you want a paradigm for fear-mongering, you can’t beat this Donald Trump quote, which combines the appearance of factuality with no actual content whatsoever:

Some really bad things are happening, and they’re happening fast. I think they’re happening a lot faster than anybody understands.

One similarity between the two panics is noteworthy: Both times Republicans attributed President Obama’s sane and measured response to his lack of loyalty to the United States. During Ebola, Jodi Ernst said Obama hadn’t demonstrated that he cares about the American people, and recently, Ted Cruz said Obama “does not wish to defend this country.”

Strangely, though, over-reacting during a panic seems to carry no political cost, because everyone forgets your excesses while they are forgetting their own. In a sane world, Chris Christie’s over-the-top response to Ebola would disqualify him from further leadership positions — especially since it turned out that the CDC was right and he was wrong. But no one remembers, so he is not discouraged from flipping his wig now as well.

[4] You know who I mean: The ones who find the Bible crystal clear when it justifies their condemnation of somebody they didn’t like anyway, but nearly impenetrable when it tells them to do something inconvenient. So the barely coherent rant of Romans 1 represents God’s complete rejection of any kind of homosexual relationship, but “Sell your possessions and give to the poor” is so profoundly mysterious that it defies interpretation.

[5] My hometown of Quincy, Illinois took in a bunch of them after they were expelled from Missouri in 1838. That event has its own little nook in the local history museum, because generous decisions are the ones descendants are proud of.

BTW, you read that right: The Mormons were expelled from Missouri. Just as pre-Civil-War states could establish slavery, they could also drive out unpopular religious groups. Didn’t hear about that in U.S. History class, did you?

So if the Trump travel ban isn’t about terrorism, what is it about? Nativism.

So if the Trump travel ban isn’t about terrorism, what is it about? Nativism.

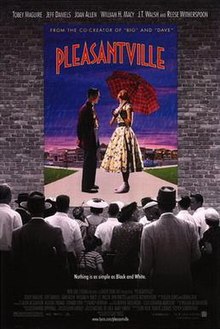

It’s easy to imagine that this mid-20th-century

It’s easy to imagine that this mid-20th-century

In a democracy it’s different: We are the wave. Politicians really do respond to certain kinds of

In a democracy it’s different: We are the wave. Politicians really do respond to certain kinds of

I know you think your flag says something positive. But you need to understand that your intention does not control the message. You’re not saying what you think you’re saying.

I know you think your flag says something positive. But you need to understand that your intention does not control the message. You’re not saying what you think you’re saying.