We’ve seen the good and bad sides of the American drug and insurance industries.

In 1996, my wife Deb was diagnosed with breast cancer. It had already spread to nearby lymph nodes, so the possibility that she would die (as her mother had just a few years before) was very real. We hit the cancer with everything the 1990s medical arsenal had to offer, on the theory that we would really only get one shot at it: If it came back, she’d probably die from it.

In 2003, it looked like it had come back. Or at least something was growing in the space between Deb’s stomach and liver. If it wasn’t a recurrence of the breast cancer, it was probably stomach or liver cancer, each of which was its own death sentence. A biopsy didn’t yield any definite results, and the tumor quickly grew to about the size of a soccer ball by the time a surgeon took it out. (It took 54 staples to close the incision.) I tried to stay as hopeful as I could, but deep down I was expecting her to die in a year or two.

The soccer ball turned out to be a gastro-intestinal stromal tumor (GIST), which only a year or two before would have been yet another death sentence. GISTs were impervious to standard turn-of-the-millennium chemotherapy, and they nearly always came back after surgery.

Fortunately for us, though, there was a new drug. Gleevec had been developed for treating leukemia, but it turned out to work on certain kinds of GISTs also, or at least the trials looked good. The short-term statistics were excellent, and the anecdotal reports were full of miracle stories where tumors just went away overnight. Long term … who knew? But long-term problems were things we could worry about in the long term. Deb’s oncologist Roger Lange (who we loved and she eventually outlived) said, “It looks like you haven’t used up your nine lives yet.”

That was the last we’ve seen of GISTs. For nearly 16 years, she’s been taking Gleevec or a generic equivalent. There are side effects (mainly a general loss of energy that exaggerates the effects of normal aging), but she can live with them. Literally.

So three cheers for modern drugs and the pharmaceutical industry that makes them! They save lives.

Wouldn’t it be great if that were the whole story? But in America, medical stories are never just about medicine. They’re also about money.

What’s your life worth to you? The economic aspect of Gleevec has always been controversial. It is made by Novartis, a private company whose purpose isn’t to save lives, but to make money for its shareholders. The drug presumably cost a lot to develop and has a small market, but for that small number of people it is literally the difference between life and death. So they should be willing to pay a lot of money, right?

That was the thinking when Novartis launched Gleevec in 2001, charging a hefty $26,400 per patient per year for the drug, a price that was then estimated to recoup development costs in two years, with profits accruing thereafter. And then something strange happened: The price kept increasing, year by year, even though alternative drugs began to hit the market. In fact, the alternatives seemed to draw Gleevec’s price upward: New drugs were introduced at even higher prices, so why shouldn’t Gleevec cost more too?

The result was that when its patent on Gleevec expired in 2015, Novartis was charging $120,000 per patient per year. (As I bounce from one reference article to the next, the prices quoted don’t line up exactly. I’m not sure why. All the articles I link to agree on the general direction of prices.) The original price was already profitable, but the increased price made Gleevec a blockbuster drug that brought in $4.7 billion a year.

Patents and generics. Outrageous as it sounds, from an investor’s point of view that’s how the system is supposed to work. Medical research is hard and costly, and a lot of it doesn’t yield any marketable products. So each successful drug has to pay not just for its own development costs, but also for all the once-similarly-promising drugs that failed. It’s precisely because blockbuster drugs can earn so much money that companies invest the resources to develop them. So I can claim that Gleevec shouldn’t cost this much, but if it didn’t, maybe it wouldn’t have been developed to begin with. And maybe Deb would be dead by now.

So OK: Big profits are a necessary evil that produces a greater good. At least that’s the theory.

If you develop a drug, you can get a patent on it that lasts 20 years from when you submitted the patent application. Typically you submit well before the drug comes to market, so you end up with 15 years or so of a monopoly on a marketable drug. As a monopolist, you can charge pretty much what you want. And if your drug is uniquely applicable to certain desperate patients, they’ll pay it if they can.

But eventually your patent runs out, and then your drug is just a chemical that any good chemical company should be able to synthesize, producing what is known as a generic drug. Generics still have to go through trials to prove that they work more-or-less as well as the original, but that process is nowhere near as risky, costly, or time-consuming as what the innovating company had to do: A generic-drug company begins with the knowledge that something like this works, and has a drug it can reverse engineer. So it’s an engineering problem, not a medical research problem.

In Gleevec’s case, the generic is known as imatinib mesylate. By now a number of companies make it, so you might expect the magic of market competition to take hold.

In the case of Lipitor (the anti-cholesterol drug that is the the drug industry’s all-time revenue champion), prices dropped about 80% after the patent expired. An even better example is aspirin: a 500 tablet bottle will cost you about $9, unless it’s on sale. Aspirin is so well understood and is produced by so many companies that the retail price is getting close to the cost of production. But a particularly bad example is insulin: It’s been around for a century or so, but lately its price has been skyrocketing. The Washington Post Magazine reports:

In the past decade alone, U.S. insulin list prices have tripled, according to an analysis of data from IBM Watson Health. In 1996, when Eli Lilly debuted its Humalog brand of insulin, the list price of a 10-milliliter vial was $21. The price of the same vial is now $275.

… The global insulin market is dominated by three companies: Eli Lilly, the French company Sanofi and the Danish firm Novo Nordisk. All three have raised list prices to similar levels. According to IBM Watson Health data, Sanofi’s popular insulin brand Lantus was $35 a vial when it was introduced in 2001; it’s now $270. Novo Nordisk’s Novolog was priced at $40 in 2001, and as of July 2018, it’s $289.

The insulin-producing companies don’t even have the excuse of a small market: About 7 million Americans need insulin.

Gleevec has been more like insulin than aspirin: The generic drug companies haven’t really tried to undercut Novartis’ price. When the first generic hit the market, Gleevec was going for about $9,000 a month; the generic was priced at $8,000. Additional generic manufacturers entering the market didn’t increase that gap much.

At least, that’s what happened in the United States. In 2016, a doctor predicted:

Today, health care is globalized, and there are more than 18 generic imatinib versions available worldwide, including 3 in Canada. Generic imatinib is sold at $8,800/year in Canada and at about $400/year in India. The cost to manufacture a 1-year supply of 400-mg imatinib tablets is $159. Two years from now, the price of generic imatinib in the United States (or purchased from abroad) will be significantly lower, hopefully less than $1,000/year.

But that didn’t happen. Instead, the price has remained in the $90K-$120K range.

If you’re surprised that a generic whose annual per-patient cost of production is $159 would sell for close to $100,000, you’re not thinking like an oligopolist. Sure, you could sell imatinib mesylate for $200 a year, but why would you? People are paying $8,000 a month. Why rock that boat?

At the moment 20 states, led by Connecticut, are suing a number of generic drug makers, accusing them of price-fixing. Imatinib mesylate was not named in the original suit, but the general practices described apply to a lot of drugs. Connecticut’s assistant attorney general Joseph Nielsen describes the generic drug industry as “most likely the largest cartel in the history of the United States“.

Insurance and Medicare. If you’ve been doing the math — between $30K and $120K a year for 16 years — you must be wondering what kind of plutocrats Deb and I must be (or at least must have been when all this started) that we’re not bankrupt yet. But in fact, for most of that time very little of that cost passed through to us. Deb worked at a company that had very good insurance. And when she retired, we were allowed to keep that insurance as long as we paid our own premiums.

So in the same way that I have to be thankful to the pharmaceutical industry, I also have to be thankful to the insurance industry. Over the years, they have spent a whole lot more money on us that we spent on them.

(I have, of course, wondered what happens to GIST survivors who don’t have good insurance. The effect of the drug is invisible — the evidence that it’s working is that nothing happens — so I can imagine the temptation to just stop taking it rather than bankrupt your family.)

Unfortunately, though, Deb’s company’s insurance only carried her until age 65, when she was expected to sign up for Medicare. That happened in October (though for reasons not worth getting into, she didn’t need to worry about it until the new coverage year started this month). But OK, Medicare has Part D, which covers prescription drugs. So we’ll be OK, right?

Signing up for Part D involves choosing among a bunch of plans that are underwritten by private insurance companies. Wikipedia describes the situation like this:

Because each plan can design their formulary and tier levels, drugs appearing on Tier 2 in one plan may be on Tier 3 in another plan. Co-pays may vary across plans. Some plans have no deductibles and the coinsurance for the most expensive drugs varies widely.

In short, if you expect to need an expensive drug, you need to do your research before you pick a plan. What if you’re old and never used the internet much, or just kind of confused in your thinking? Well, you might be out of luck.

But Deb is computer savvy and diligent, so she searched the various companies’ online pricing tools until she found a plan that quoted a good price on generic Gleevec:

Ignoring the details of the various $300-something monthly charges, the annual cost was estimated at $4069.55. Not cheap, but well below the what-is-your-life-worth level, and for some reason significantly cheaper than other plans from the same company.

Estimates are not promises. She did that research in November, when decisions for the 2019 coverage year had to be made. So imagine our surprise when she went to fill her first monthly imatinib prescription in January, and discovered that it cost $2,881.07!

Your first thought, like ours, might be that something drastic had happened to the imatinib market between November and January. But no: At the same time that SilverScript was charging us $2,881.07, their pricing tool was still showing prospective customers that the price would be $348.06.

Hours spent on the phone with a wide range of SilverScript employees yielded her nothing: Yes, there was a factor-of-8 gap between the pricing estimate (which they were still showing on their web site) and the price they were actually charging us. And no, this isn’t like Wal-Mart, where they usually honor the price they display, even if it’s a mistake. (And is it a mistake? They don’t seem to be in any hurry to correct it. Maybe it’s intentional deception.) The letter we got from the grievance department says:

Please note that copays are estimates only. We are unable to provide exact copays until such time as the prescription is processed.

And if they’re quoting you one price at the exact same moment that they’re charging a drastically higher price to someone just like you, that’s just the way it goes. Maybe you should pick a different insurance company next year, based on their (possibly inaccurate) pricing information.

What happens after next month? The people who weren’t still quoting the $348.06 price were telling Deb that $2881.07 was what we could expect going forward, or maybe even something higher. So we were looking at an annual cost in the neighborhood of $30,000.

Think about what that would mean: After generics, after insurance, we’d be paying the full price that Novartis originally charged for Gleevec.

But hey, what’s your life worth?

Fortunately, though, it turned out that the SilverScript people who were quoting those prices didn’t know what they were talking about either. (Again, though, I have to wonder what is a mistake and what is intentional. If the low-price information was intended to get us to commit to their program for 2019, maybe the high-price information was intended to make Deb reconsider whether she really wanted to keep taking this drug. Because the ideal health-insurance customer is somebody who pays premiums but doesn’t use services.) Or at least that’s how it appears right now.

For some reason, nobody at SilverScript mentioned the Medicare Donut Hole. (A Blue Cross person explained it when Deb was researching whether she could switch to another Part D plan after the year started.) Follow the link if you want a more complete explanation, but what it means for us is that after we spend $5,100, we hit the catastrophic coverage phase, where the insurance starts to cover 90% of the drug’s cost. If that’s really how things play out (we’re not fully believing anything we read at this point), our annual costs will wind up being something like what the SilverScript web site was predicting for the plans we didn’t choose: Around $10,000 rather than $4,000 or $30,000.

It’s weird: After you’ve spent a week or so wondering where you’re going to come up with an extra $30,000 each year, $10,000 sounds pretty good. It’s not pocket change, but we can afford it. It beats going off the drug and finding out for sure whether it is still necessary.

The lessons I draw. There are ambiguous lessons to learn from our experience. On the one hand, thanks to drug research and health insurance, Deb is alive and we’re not bankrupt. The most important stuff has turned out well, at least so far.

But on the other hand, it seems obvious to me that this system is full of waste and corruption. Novartis should never have been able to charge such a high price for Gleevec, and there was absolutely no reason why the generic drug companies should have been able to share in those windfall profits. In theory, once patents expire the free market will drive prices down. But in the real world that doesn’t happen. Instead, a few companies divide the pie among themselves. They know they have a good thing going, and they aren’t going to ruin it by undercutting each other’s prices.

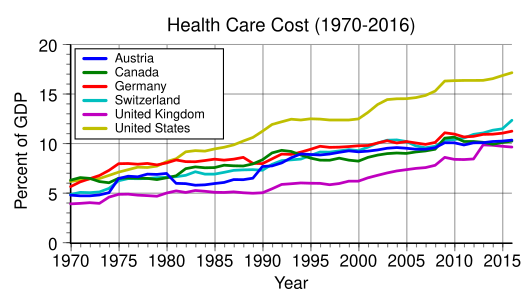

The market will never fix this, so government needs to get involved.

And why exactly is health insurance still in the private sector rather than being part of the government? The justification I usually hear is that the profit motive will produce better customer service and more efficient delivery of services. I don’t see anything in our personal experience to support that notion. To me, it looks like companies are motivated to lie to us, and none of the insurance people we have dealt with seem to be oriented towards the mission of helping people and saving lives.

When Deb was dealing with the SilverScript grievance people, she reported that they appeared to be following a script rather than trying to understand her case. Nobody seemed to grasp the idea that they were participating in a bait-and-switch fraud, or to be particularly upset if they were. Listening to her account of the conversations, I found myself wishing she had asked, “In your job dealing with grievances, have you ever actually helped anybody?” That question wouldn’t have improved our outcome in any way, but I’d just like to know.

Personally, I’d rather take my chances with government bureaucrats. People in the government may be insulated from market forces, but often they identify with the mission of their office. For example, I recently had to change my drivers’ license from New Hampshire to Massachusetts. I ran into all sorts of unexpected bureaucratic problems; for some reason, none of my documents were the exact ones the system was looking for. Through it all, though, the clerk I was dealing with did her best to guide me through the labyrinth. In her mind, she was there to help people.

That’s not the impression Deb got from SilverScript. The company isn’t trying to provide healthcare or help its customers find ways to pay for it; it’s trying to make as much money off of them as it can. The grievance department isn’t there to respond to customers’ legitimate grievances, it’s there to mollify and divert people who have been conned by the company’s deceptive practices. The individuals who work there are probably no worse than the rest of us, so they can’t identify with that mission. Instead, they sink into their scripts.

My bottom-line conclusion is that the profit motive is not serving us in health care. There has to be a better way.