This was a bad, pointless war, and I’m glad the US will soon be out of it. No number of talking heads will convince me otherwise.

Last Monday afternoon, President Biden committed an unforgivable sin: He didn’t apologize for his decision to leave Afghanistan.

The choice I had to make, as your President, was either to follow through on [the Trump administration’s] agreement or be prepared to go back to fighting the Taliban in the middle of the spring fighting season.

There would have been no ceasefire after May 1. There was no agreement protecting our forces after May 1. There was no status quo of stability without American casualties after May 1.

There was only the cold reality of either following through on the agreement to withdraw our forces or escalating the conflict and sending thousands more American troops back into combat in Afghanistan, lurching into the third decade of conflict.

I stand squarely behind my decision. After 20 years, I’ve learned the hard way that there was never a good time to withdraw U.S. forces.

That speech led to what TPM’s Josh Marshall called “peak screech” from the DC media. In Tuesday’s morning newsletter from Politico, Marshall elaborates, “A sort of primal scream of ‘WTF, JOE BIDEN?!?!?!!?!’ virtually bleeds through the copy.”

Immediately after Biden’s speech, MSNBC’s Nicole Wallace offered this blunt assessment of a mainstream that her show itself was often swimming in:

Ninety-five percent of the American people will agree with everything [Biden] just said. Ninety-five percent of the press covering this White House will disagree.

Her numbers were exaggerated, but the overall point was dead-on: I can’t remember the last time the media was so unified and so intent on talking me out of my opinion.

This was not a question of facts that they knew and I didn’t. The mainstream media has been equally unified in combating misinformation about the Covid vaccines, say, or in batting aside Trump’s self-serving bullshit about election fraud. But in each of those cases, there is a fact of the matter: The vaccines work. Fraud did not decide the election.

But Afghanistan is different. The belief that our troops should have stayed in Afghanistan a little bit longer (or a lot longer or forever) is an opinion about what might happen in the unknowable future. It’s also a value judgment about the significance of Afghanistan to American security compared to the ongoing cost in lives and money. Reasonable people can disagree about such things.

But apparently not on TV. The Popular Information blog talked to “a veteran communications professional who has been trying to place prominent voices supportive of the withdrawal on television and in print”.

I’ve been in political media for over two decades, and I have never experienced something like this before. Not only can I not get people booked on shows, but I can’t even get TV bookers who frequently book my guests to give me a call back…

I’ve fed sources to reporters, who end up not quoting the sources, but do quote multiple voices who are critical of the president and/or put the withdrawal in a negative light.

I turn on TV and watch CNN and, frankly, a lot of MSNBC shows, and they’re presenting it as if there’s not a voice out there willing to defend the president and his decision to withdraw. But I offered those very shows those voices, and the shows purposely decided to shut them out.

In so many ways this feels like Iraq and 2003 all over again. The media has coalesced around a narrative, and any threat to that narrative needs to be shut out.

Paul Waldman noticed the same thing:

As we have watched the rapid dissolution of the Afghan government, the takeover of the country by the Taliban and the desperate effort of so many Afghans to flee, the U.S. media have asked themselves a question: What do the people who were wrong about Afghanistan all along have to say about all this?

That’s not literally what TV bookers and journalists have said, of course. But if you’ve been watching the debate, it almost seems that way.

So Condoleezza Rice, of all people, was given an opportunity to weigh in. (She said the 20-year war needed “more time”.) The Wall Street Journal wanted to hear from David Petraeus, who “valued, even cherished, the fallen Afghan government”. Liz Cheney, whose father did more to create this debacle than just about anyone, charged that Biden “ignored the advice of his military leaders“, as if that advice had been fabulous for the last 20 years.

A parade of retired generals, military contractors, and think-tank talking heads were given a platform to explain how Biden had made a “terrible mistake“, that was “worse than Saigon“, and that pushed his presidency past “the point of no return“. Afghanistan has ruined the Biden administration’s image of competence and empathy, and it will “never be the same“.

As we saw with the beginning of these wars in 2001-2003, these moments of unanimity allow a lot of dubious ideas to sneak in to the conversation. Let’s examine a few of them.

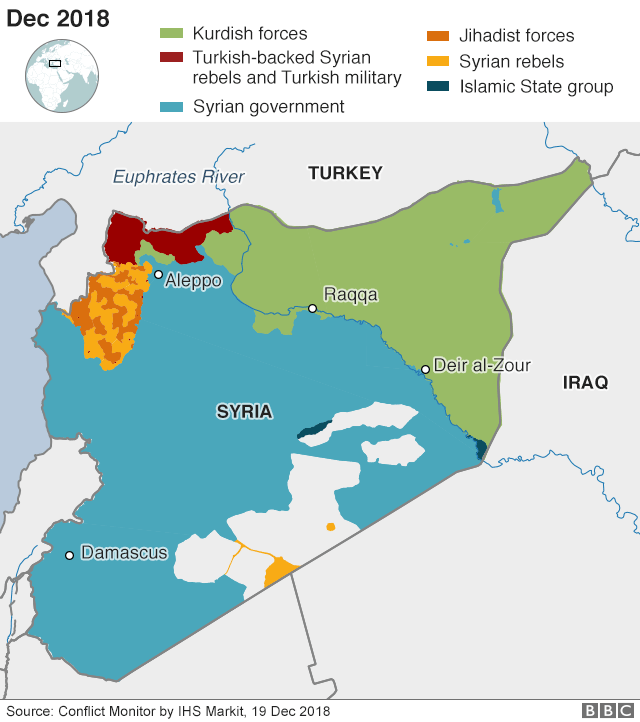

Yes, this was a “forever war”. One false idea I keep hearing is that Afghanistan had settled down to the point where a minimal US commitment could have held it steady: maybe 2-3 thousand troops that would rarely take any casualties. Jeff Jacoby was one of many pushing this point:

Yes, the United States has been involved in Afghanistan for almost 20 years, but the last time American forces suffered any combat casualties was Feb. 8, 2020, when Sgt. Javier Gutierrez and Sgt. Antonio Rodriguez were ambushed and killed. Their sacrifice was heroic and selfless. But it makes little sense to speak of a “forever war” in which there are no fatalities for a year and a half. Nor does it make sense to apply that label to a mission involving just 2,500 troops, which was the tiny size to which the US footprint in Afghanistan had shrunk by the time Biden took office.

And The Washington Post made space for Rory Stewart to claim:

When he became president, Biden took over a relatively low-cost, low-risk presence in Afghanistan that was nevertheless capable of protecting the achievements of the previous 20 years.

But you know what else happened in February of 2020? Trump’s peace agreement with the Taliban. Once Trump agreed to totally withdraw, the Taliban stopped targeting US troops. The “low-cost, low-risk” presence depended on the Taliban believing our promise to leave. If Biden had suddenly said, “Never mind, we’re keeping 2,500 troops in place from now on.”, we’d soon start seeing body bags again, and realizing that 2,500 troops weren’t enough. Biden was right: “There was no status quo of stability without American casualties after May 1.”

Popular Information points out the hidden cost to the Afghans of our “light footprint”:

With few troops on the ground, the military increasingly relied on air power to keep the Taliban at bay. This kept U.S. fatalities low but resulted in a massive increase in civilian casualties. A Brown University study found that between 2016 and 2019 the “number of civilians killed by international airstrikes increased about 330 percent.” In October 2020 “212 civilians were killed.”

Jacoby invokes the example of Germany, where we have kept far more than 2,500 troops for far longer than 20 years. “Should we call that a forever war, too?” No, because Germany has no war. If Nazi partisans were still hiding in the Bavarian mountains, which we regularly pounded with air power, and if we worried about them overthrowing the Bundesrepublik as soon as our troops left, that would be a forever war in Germany. Is that really so hard to grasp?

Actually, no one saw this coming. Much has been made of the few intelligence reports that warned of the Afghan government falling soon after we left. But if that had actually happened, we’d have been OK — or at least better off than we are.

What did happen, though, is that the Afghan army dissolved and the leaders fled Kabul before we were done leaving. That’s why we’re having the problems we’re having. And literally no one — certainly not the “experts” who are denouncing Biden on TV — predicted that.

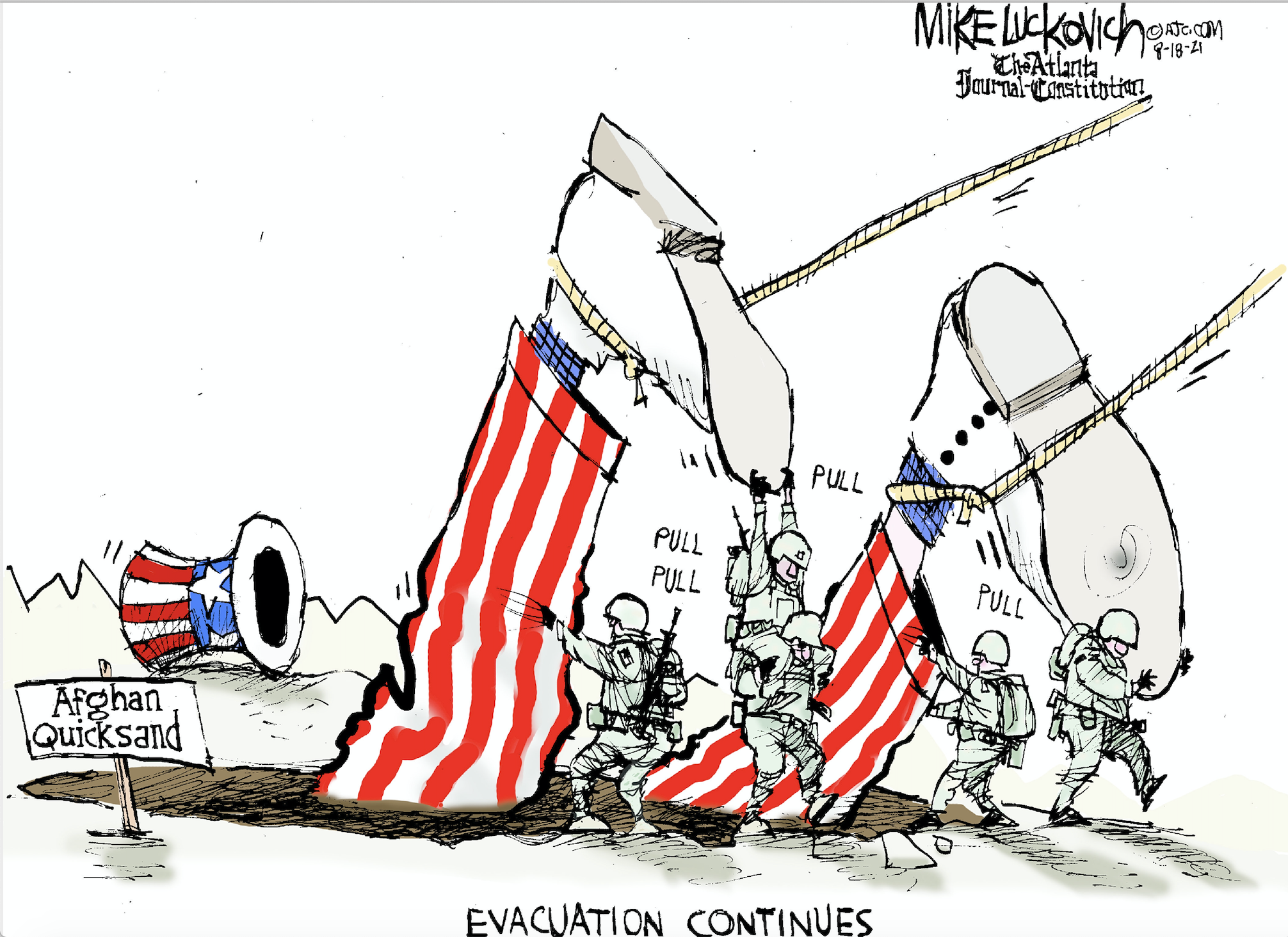

Evacuating our people sooner wouldn’t have avoided the problem. Imagine you’ve spent the evening in the city, and as you go through the subway turnstile you see the last train home vanishing down the tunnel. Naturally, you think “I should have left the party sooner.”

Commentators are thinking like that now, but the metaphor doesn’t work. In the metaphor, you and the train are independent processes. If you’d arrived at the station five minutes earlier, the train would have been waiting and you’d have gotten home.

The fall of Saigon in 1975 was exactly like a train leaving: It took time for the North Vietnamese/Viet Cong forces to fight their way to Saigon. If you didn’t get out before they arrived, you should have started leaving sooner.

But the Taliban didn’t fight their way to Kabul; the Afghan army we had so lavishly equipped simply dissolved in front of them, in accordance with surrender deals previously worked out. And the signal that started the surrender was the Americans beginning to leave. Nobody wanted to be the last person to wave the white flag, so when they saw Americans evacuating, it was time.

In other words: Afghanistan is more like the train operator being in contact with someone at the party, so that he could start pushing off as soon as you were on your way.

So yes, Biden could have started pulling out a month or two sooner. And the collapse would have happened a month or two sooner. Again, Biden nailed it: There was never a good time to leave Afghanistan.

Imagine if Biden had foreseen everything and been transparent about it. So in June or July he goes on TV and says, “The Afghan Army isn’t going to fight, so the government going to fall very suddenly. If you want to be part of the evacuation, start off for the airport now.”

Not only would the collapse have begun immediately, but all the Liz Cheney and David Petraeus types would claim that Biden had stabbed the Afghans in the back. Biden’s lack of faith, they would claim, and not the Afghan government’s failings, would have been to blame.

And now picture what happens to the politics of welcoming the Afghan refugees. Tucker Carlson and the other nativist voices are already claiming the Afghan rescue is part of the massive Democratic plot to replace White Americans with immigrants. “First we invade, then we’re invaded.” Laura Ingraham echoed that concern:

All day, we’ve heard phrases like “We promised them.” Well, who did? Did you?

How much more weight would this immigration conspiracy theory have, if the first visible sign of collapse had been Biden expressing his lack of faith in the Afghan government? Clearly, replacement theorists would argue, Biden wanted Afghanistan to collapse so that he could bring in more immigrants — possibly “millions” of them, as Carlson has already warned.

The war, and not the end of the war, is what lowered America’s standing in the world. I can’t put this better than David Rothkopf already did when he listed “the top 30 things that have really harmed our standing”. His list is more Trump-centered than mine would be — I’d give a prominent place to the Bush administration’s torture policy — but we agree on this: Having things go badly for a few weeks while we’re trying to do the right thing is not on it.

Spending 20 years, thousands of lives, and trillions of dollars fighting a war that, in the end, accomplished little — that lowers our standing in the world. Ending that war doesn’t.

So what explains the “peak screech”? I’m sure someone in the comments will argue that the DC press corps is part of the corrupt military-industrial complex that has been profiting from the continuing war, but I’m not going there. (In general, I am leery of the assumption that the people who disagree with me are corrupt. That assumption gives up too easily on democracy, which requires good-faith exchanges of ideas between disagreeing parties. I’m not saying there is no corruption and bad-faith arguing, but I have to be driven to that conclusion. I’m not going there first.)

Josh Marshall offers a two-fold explanation, which rings true for me. First, the major foreign policy reporters have personal connections to a lot of the people who are at risk in Afghanistan, or to people just like them in other shaky countries. If you reported from Afghanistan, you had a driver, you had an interpreter. Maybe your cameraman was Afghan. You depended on those people, spent a lot of downtime with them, and maybe even met their families. Maybe their street smarts got you out of a few difficult situations. Will they now be killed because they helped you? You never committed to bring them to America, which was always beyond your power anyway. But you can’t be objective about their situation.

Second is a phenomenon sometimes described as “source capture”. A big part of being a reporter is cultivating well-placed sources. For war reporters, that means sources in the Pentagon or the State Department, or commanders in the field, or officials in the Afghan government or military. Even if you have no specific deal with these sources, you always understand the situation: If you make them look bad, they’ll stop talking to you.

Over time, as you go back to your sources again and again, you start to internalize that understanding, particularly with the ones who consistently give you reliable information. You identify with them. You stop thinking of them as your sources and start to think of yourself as their voice. If they are invested in a project like the Afghanistan war, you start to feel invested in it too.

Marshall sums up:

[W]hat I’m describing isn’t a flag-waving, America’s never wrong, “pro-war” mindset. It’s more varied and critical, capable of seeing the collateral damage of these engagements, the toll on American service members post combat, the corruption endemic in occupation-backed governments. And yet it is still very bought-in. You see this in a different way in some of the country’s most accomplished longform magazine writers, many of whom have spent ample time in these warzones. Again, not at all militarists or gungho armchair warriors but people capable of capturing the subtleties and discontents of these missions and the individuals caught up in their storms. And yet they are still very bought-in. And it is from these voices that we are hearing many of the most anguished accusations of betrayal and abandonment. It is harrowing to process years or decades of denial in hours or days.

What we see in so many reactions, claims of disgrace and betrayal are no more than people who have been deeply bought into these endeavors suddenly forced to confront how much of it was simply an illusion.

If the last two weeks have revealed anything, it’s exactly how much of an illusion our “nation-building” in Afghanistan always was. Real countries, with real governments and real armies, don’t evaporate overnight.

People who have been living in denial typically react with anger when their bubble pops. They ought to be angry at the people who duped them, or at themselves for being gullible. But that’s not usually where the anger goes, at least not at first. The first target is the person who popped the bubble.

So damn that Joe Biden. If he’d just kept a few thousand troops deployed and kept the money spigot open, we could all still be happy.

/https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thestar/opinion/editorial_cartoon/2020/01/07/theo-moudakis-lies-to-date/theo_moudakis_lies_to_date.jpg)