A higher retirement age, an abortion ban, more tax cuts for corporations and the rich, less regulation, an end to wokeness, and to burn as much fossil fuel as humanly possible. And that’s not all.

Wednesday, the House Republican Study Committee put out a report on its budget proposals for FY 2025, which begins in October. The mainstream media publicized a few of its more controversial features, like recommending an increase in the retirement age, federally banning abortion by giving fertilized ova 14th Amendment rights, and reversing nearly everything that would hasten the day when sustainable energy replaces fossil fuels.

But the report is 180 pages, and you can’t really appreciate the steady drumbeat of wrongheadedness until you read the whole thing (which I did). This article summarizes the report in some detail. But first, let me justify why this document deserves your attention.

How political parties communicate their vision. Ordinarily, there are several ways you can figure out what a political party stands for:

- position papers of the party’s nominee

- a detailed platform passed by the national convention

- bills they pass in any house of Congress they control, even if those bills fail in the other chamber or get vetoed by the president

Unfortunately, none of that works with today’s GOP. Apparently, having an “Issues” page on your campaign website is an obsolete idea. Googling either “Donald Trump for President” or “Joe Biden for President” will take you to a fundraising page with no “Issues” tab. Adding “issues” to the search helps a little with Biden, but not Trump. The Biden search will lead you to a “Priorities” page at WhiteHouse.gov, but it’s a bit out of date. (Covid-19 is still the first priority mentioned.) For Trump you’ll be directed to various news outlets’ summaries of what he stands for, not an official statement by the Trump campaign.

Of course, you could instead listen to what Trump says in his speeches, if you can make any sense out of them, beyond grasping Trump’s desire for revenge against the long list of people he feels have wronged him. As I described last week (after his “bloodbath” remark), he tends to speak in word salads that allow his partisans to claim that he didn’t really mean whatever part of his speech you found alarming.

As for platforms, the Democrats passed a fairly detailed one in 2020, which (again) is a little out of date. For example, it says “We will maintain transatlantic support for Ukraine’s reform efforts and its territorial integrity.”, but that was before Russia’s full-scale invasion started.

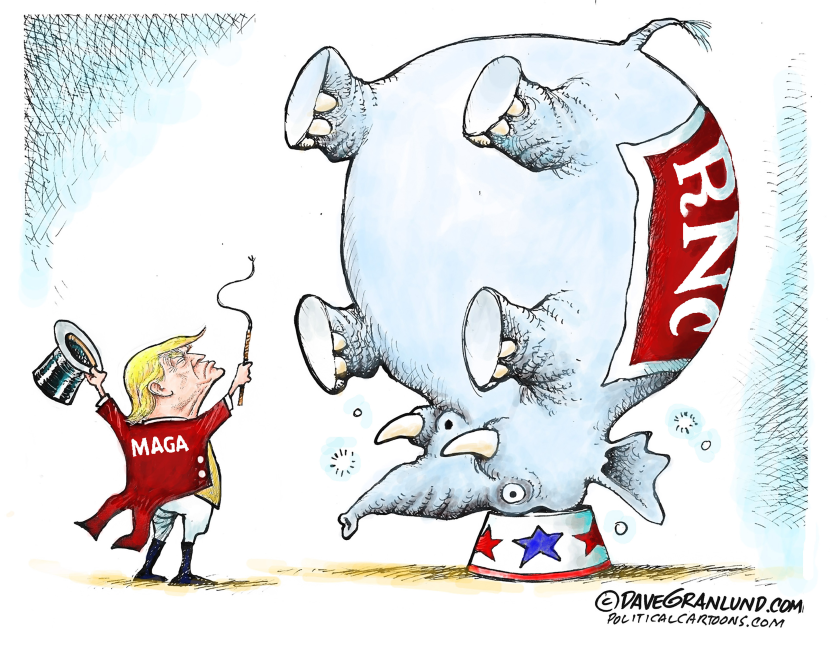

The Republicans don’t even offer that much. Their 2020 “platform” complains a lot about the media misrepresenting the Party’s positions, but says “the 2020 Republican National Convention will adjourn without adopting a new platform until the 2024 Republican National Convention”. What it does say is that “the Republican Party has and will continue to enthusiastically support the President’s America-first agenda”. In short: We’re for a man, not a set of ideas.

In 2021-2022, the Democrats had a House majority, but only a 50-50 position in the Senate with two Democratic senators unwilling to do away with the filibuster. So in addition to bills that became law, like the American Rescue Plan, Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, Inflation Reduction Act, CHIPS Act, Respect for Marriage Act, and so on, Nancy Pelosi’s majority passed a flurry of bills that died in the Senate: the Joe Lewis Voting Rights Act, For the People Act, George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, and a long list of others.

But the Republican majority that has controlled the House in 2023-2024 is almost completely unable to pass legislation. Simply keeping the government open has been a struggle, which finally came to a conclusion Friday, halfway through FY 2024.

Instead, their time has been dominated by battles over the speakership and investigations of the Biden family that have produced little more than talking points to raise on Fox News. The only major bill I could find that passed the House and died in the Democratic Senate was the Secure the Border Act, which would have funded a border wall and reinstituted President Trump’s wait-in-Mexico immigration policy.

So OK, you might conclude that Republicans at least have a position on the border. Of course, when Democrats tried to offer them most of what they wanted on that issue, they turned it down, preferring to retain the border as a talking point rather than take any action on it. So maybe they care about the border and maybe they don’t.

There are other places you might look to find a Republican vision for the future, but most of them are by outside groups: The Heritage Foundation, for example, has put together Project 2025, which Mother Jones has described as “a blueprint for a wannabe-White-House-autocrat”. That vision calls for undoing any effort to avoid a climate catastrophe, dismantling the civil service, and a few other things.

But that’s the Heritage Foundation, not any official GOP group. So it’s deniable.

The House Republican Study Committee report, on the other hand, actually is something. This committee is not the whole Republican conference, but it’s close: Its membership includes 166 of the 218 (or so) House Republicans. By itself, it’s the “majority of the majority” of House Republicans’ Hastert Rule. The intro letter is promising (other than the apostrophe missing in its first line – “the President of the United States cognitive decline”):

The RSC budget for Fiscal Year (FY) 25 does not shy away from the severity of the challenges America faces. As any family knows, attempting to live within your means when you are in debt is challenging. The RSC budget provides a sober pathway to balance the budget, reduce prices, preserve the programs Americans have paid into, and create economic growth and opportunity. As in previous years, the RSC budget also celebrates the work of House conservatives who have fought for legislation that preserves American values, combats Biden’s woke and weaponized government, and protects the freedoms that should be enjoyed by every American.

So OK, let’s go. What’s in it? Let’s take the sections in order.

Deregulation. This is the first section of the plan, and I was immediately unimpressed. The section’s second paragraph is:

The cost of federal regulations in 2022 was estimated to be $1.939 trillion—amounting to 7.4 percent of GDP.[footnote 1] To contextualize, the total amount of individual income tax revenues for 2022 was $2.263 trillion.[2] Despite the high fiscal toll on the American people, the Biden administration has continued to push for regulation after regulation.

Footnote [1] is a report by the Competitive Enterprise Institute, a libertarian think tank known for climate-change denial. And while that report does contain the $1.939 trillion estimate, it sends you to another footnote, and I was unable to track down what this number really means.

In general, conservative estimates of the “cost” of regulation ignore any balancing consideration of the benefits. For example, a regulation forcing utilities to replace lead water pipes with something less toxic will cost them money. However, the children whose brain development is not compromised by that lead will grow up to be more intelligent, more productive, and less likely to commit crimes (because lead exposure affects impulse control). So even if we ignore moral considerations and just talk about dollars, those are real economic benefits that any honest appraisal would have to weigh against the costs. But the CEI doesn’t do that kind of stuff.

Among the specific Biden administration regulations the RSC report calls out is “A Green New Deal emissions proposal that will make vehicles significantly more expensive”. Again, the costs of not regulating carbon emissions are ignored: stronger hurricanes, more wildfires, longer droughts, etc. The RSC targets any effort to avoid or mitigate climate change by reducing fossil fuel dependence. So: more drilling, more pipelines, less conservation, more gas-guzzling vehicles, and less accountability for energy companies.

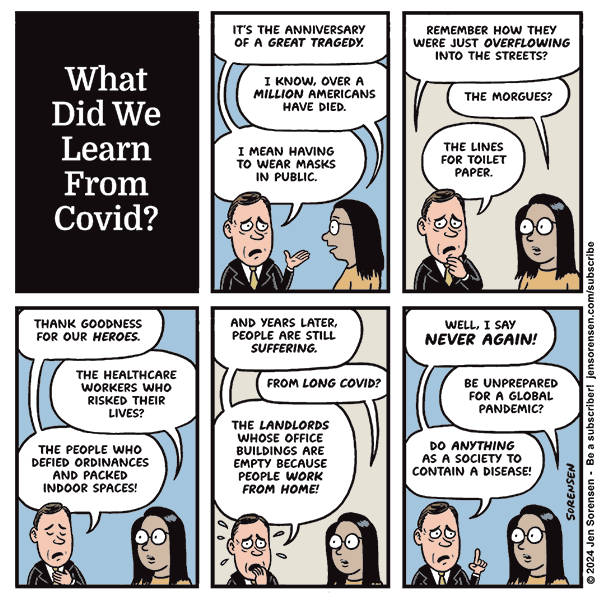

A long list of proposals are backward-looking slaps at Covid regulations like vaccine or mask mandates. These proposals would tie the hands of public health officials in the next pandemic, whatever it is.

Another long list of proposals remove restraints from banks and other financial industries, allowing them to resume many dangerous and deceptive practices that were exposed after the 2008 financial collapse. A perennial Republican proposal is to do away with the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, because why would consumers ever need to be protected from predatory banks and other lenders?

But OK, reasonable people can disagree about whether current federal regulations are cost-effective, or whether we need less regulation rather than more. But the proposals endorsed in this section are unlikely to lead to wiser regulatory decisions. Most of them amount to regulating the regulators, binding agencies in red tape that will make it nearly impossible for them to stop corporations who decide to make money by, in effect, killing people.

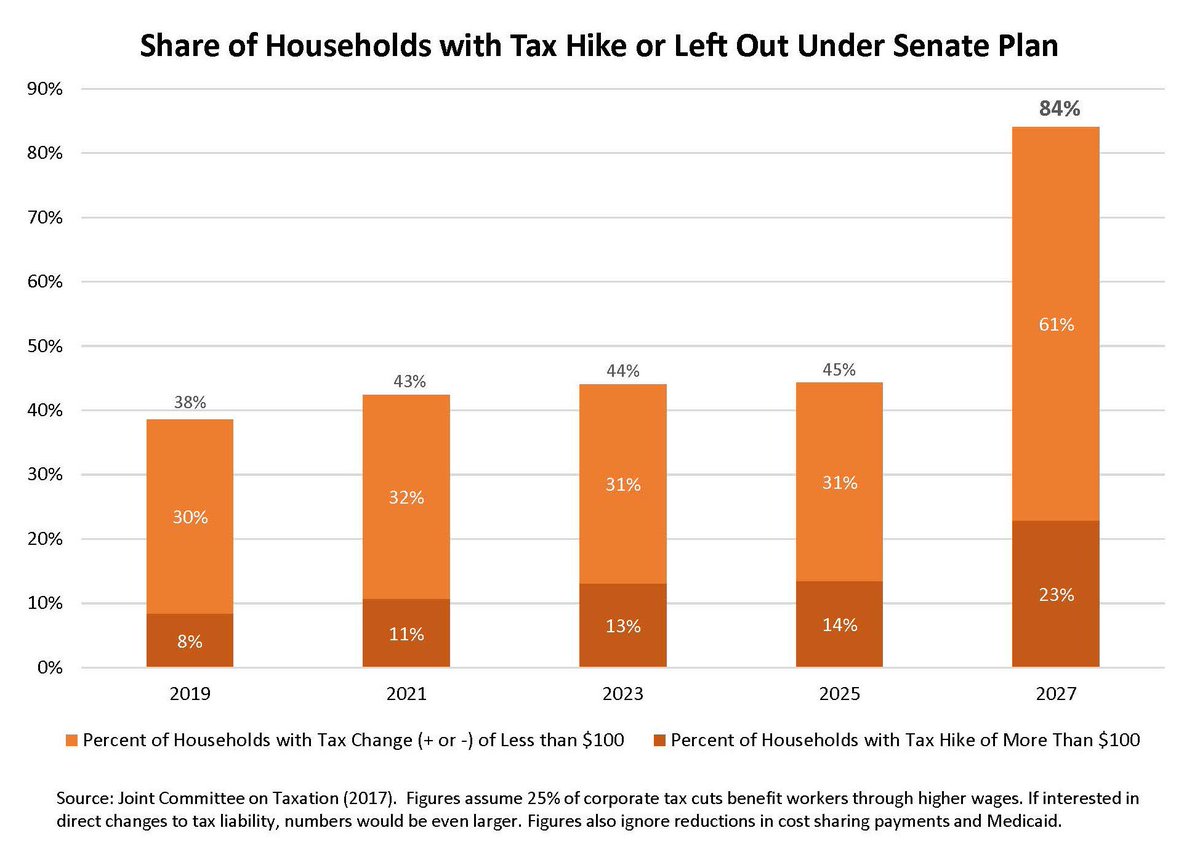

Taxes. The second section is about tax reform. You might expect Republicans to object to Biden’s tax policies, and maybe trace them back to Obama’s policies.

But no. This section begins by decrying all the taxes ever collected from Americans.

By the end of 2024, the federal government will have taken $98.9 trillion in wealth out of the hands of Americans since 1789 through taxes and other revenue.[71] To the lament of Americans everywhere, the size of government and subsequent mandatory wealth transfers have increased dramatically since the ratification of the 16th Amendment in 1913, which gave the federal government the power to tax income. From the New Deal to the Great Society, the Left has continued to tap into Americans’ hard-earned dollars to fund a bloated federal government. Put simply, bureaucrats in Washington and Democrats in Congress believe they know how to spend your money better than you.

Preach, brother! Why couldn’t the government just leave me alone to build my own interstate highway system?

The simple fact is that through government we can buy things collectively that we can’t buy as individuals: parks, clean air, defense from invaders, public health projects, and stuff like that. Precisely where to place the boundary between the public and private sectors, and how to raise the money for public-sector investments, are also questions people of good faith might legitimately argue about. But “they believe they know how to spend your money better than you” is just a stupid way to look at these questions.

And when you talk about the “bloated federal government” created by the New Deal and the Great Society, what you’re really talking about are Social Security (from the New Deal) and Medicare and Medicaid (from the Great Society). Put together, those programs make up 45% of the federal budget.

Those all fit under the general description of insurance, something government provides much more efficiently than the private sector. (To see why this is, look at medical insurance. A private insurance company devotes much of its marketing budget to making sure they attract the right kind of clients — the ones who are unlikely to get sick. But Medicare insures everybody over 65, so it can’t manipulate its client base. Also, private insurance routinely undercovers preventative care, because a company might be paying to prevent a problem that won’t appear until after the client has switched to another company.)

The HSC report makes one point about the tax system that it’s hard to argue with: “Carve-outs for special interests embody corporate cronyism”, which is bad. However, I don’t think they see the same cronies I do, because a fundamental theme of their plan is to end “high rates of taxation on investments and savings”.

I just finished doing my taxes, and, as usual, I’m appalled: Being retired, most of my income consists of dividends and capital gains, which are taxed at rates far lower than what working people pay on their wages. So even though I benefit, I see the favorable rates on investment income as “carve-outs for special interests”. Treating wages and investment income the same is what seems fair and simple to me. (Typically, the hardest part of my taxes is filling out the “Qualified Dividends and Capital Gains Worksheet”. But it saves me thousands, so I do.)

Fairest of all is cracking down on rich people who cheat on their taxes — which is why I support the Inflation Reduction Act’s increase in the enforcement budget of the IRS. (The HSC report falsely refers to this as “Providing funding to hire 87,000 new IRS agents to spy on low-and middle-income Americans.”)

And continuing their pro-global-warming agenda, the RSC wants to repeal all the fossil fuel taxes in the Inflation Reduction Act, together with any tax breaks for sustainable energy sources.

The RSC also wants to eliminate federal inheritance taxes, a.k.a. “the death tax”. Since the threshold for filing estate tax is now $13.6 million, only the estates of very wealthy people pay this tax. (If you don’t think $13.6 million sounds like wealth, you’re out of touch with the American people.)

If there’s one thing the last 50 years have proved, it’s that giving the rich tax cuts doesn’t increase revenue. But the RSC hasn’t learned this lesson.

The RSC Budget would cut taxes by nearly $5.5 trillion over the next 10 years. The pro-growth effects of these tax reductions would result in $566 billion of additional revenue.

This is what George H. W. Bush correctly called “voodoo economics” when he ran against Reagan in 1980. The RSC’s voodoo is what lets it cut taxes and claim that it produces a balanced budget.

Poverty and Welfare. The RSC report has a clear view of why people are poor: They’re lazy and need to be pushed to work more.

The RSC Budget would require all federal benefit programs be reformed to include work promotion requirements that would help people move away from dependence and toward self-sufficiency.

Here’s what the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities says about that:

Studies evaluating TANF and its predecessor’s work requirements found that the modest employment increases that occurred shortly after the requirements were first implemented faded over time (generally because most adults not subject to the requirements also found jobs, just a bit more slowly).[40] These requirements did little to reduce poverty and tended to increase rates of deep poverty (defined as income below half of the federal poverty line), rigorous evaluations found.[41] Families who lost cash assistance faced serious consequences that include higher rates of hardship, such as higher risk of homelessness, utility shutoffs, and lower school attendance among children.

Fundamentally, the Republican view of motivation is “Carrots for the rich. Sticks for the poor.” If you want rich people to do something, you have to give them a tax break or a subsidy. But if you want poor people to do something, you need to threaten them with a punishment.

But this paragraph is my favorite:

Despite two positive changes included in the Fiscal Responsibility Act, one unintended consequence was to exempt homeless individuals, veterans, and individuals aged 24 and under who were previously in foster care from the work requirement. The RSC budget supports revising existing SNAP law to ensure that these groups of people are subject to the work requirement if they do not have dependents. SNAP and our welfare system should embrace that work conveys dignity and self-sustainment and encourage individuals to find gainful employment, not reward them for staying at home.

Did you catch that? We need to be careful that we don’t reward homeless people for staying at home.

The RSC does not grasp the concept of a poverty trap, something constructive that people could theoretically do to escape poverty, but they can’t do practically because they’re too poor. For example, homeless people have trouble maintaining basic hygiene, which makes it very hard for them to get hired. But if they don’t somehow come up with jobs, we’re going to stop subsidizing their food. This is going to give them “dignity”.

Republicans also want to bundle all such programs into “block grants” that give states “flexibility to administer their own programs”. These bundles have a terrible history, because the poor can’t afford lobbyists. As a result, money in the grants tends to wind up being spent on all sorts of things other than poor people. This was at the root of the Brett Favre fraud in Mississippi.

They also want to turn child nutrition into block grants, and the report decries the “widespread fraud” in the free school lunch and breakfast program, i.e., some kids who aren’t quite poor enough are getting fed.

Defense. The RSC proposes a $895.2 billion FY 2025 defense budget, slightly more than Biden’s $850 budget. The report lists a number of things it wants to fund, but doesn’t say which ones are already in Biden’s budget.

One thing the RSC does want to do with the defense budget is fight its culture wars, eliminating any money for “woke training and programming”, such as teaching soldiers of different races, genders, and religions how to get along and respect one another. It worries about military aid to Ukraine and other nations going through international organizations that “have a history of promoting abortion or sexual orientation and gender identity programs”. It’s not enough that our money not go into such programs; the organizations associated with them are too tainted to use. It wants Defense strategy to ignore climate change, and cancels funding for efforts to run military bases on sustainable power by 2030.

DOD should not waste valuable taxpayer dollars on inefficient forms of energy. Energy needs should be met through the most cost-effective and tactically sound methods possible. The DOD should be prohibited from entering into any contract for the procurement or production of any non- petroleum-based fuel for use as the same purpose or as a drop-in substitute for petroleum. Further, the Armed Forces should be exempt from procurement requirements for clean-energy vehicles and renewable energy portfolio standards for DOD facilities.

The RSC wants to privatize as much of the military’s support positions as possible. This includes doing away with the independent school system on military bases, which is excellent.

There are long sections focused on China and Russia, but again, it’s hard to tell which proposals differ from what Biden wants to do. The report is strongly supportive of Ukraine, but does not mention that Republicans have been blocking funding since September.

The fact that Iran is “closer than ever before to a nuclear weapon” is somehow Biden’s fault, when it was Trump who cancelled the agreement that controlled Iran’s nuclear programs. The report describes Trump’s “maximum pressure” campaign against Iran as “successful”, even though this policy failed to produce the “better deal” Trump promised.

The Hamas attack on Israel is also somehow Biden’s fault, and had nothing to do with Trump’s decision to ignore the Palestinian problem entirely.

Conservative values. There’s a long section on abortion, beginning with

RSC celebrates the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision as a historic victory in the effort to defend innocent life and to return to the Constitution as it was written. … The RSC Budget applauds the following measures designed to advance the cause of life:

Then follows a long list of proposals various Republicans have advanced to limit women’s access to abortion, including ones that would federally block drug-induced abortions, prohibit abortions after the mythical six-week “fetal heartbeat”, recognize a newly fertilized ovum as a “person” under the 14th Amendment, ban abortions at 15-weeks due to mythical fetal pain, prohibit the use of fetal stem cells in research, prohibit any ObamaCare health insurance policy from covering abortion, prevent telehealth services from prescribing abortion drugs, deny federal funds to universities whose student health organizations provide abortions, and dozens of others.

The report endorses a similar list of anti-critical-race-theory proposals, which ban teaching or promoting “critical race theory” in all sorts of settings. No one can define CRT, but as best I can tell, any recognition of White privilege in America or any truthful recounting of America’s racial history violates these proposed laws.

A number of proposals to protect gun rights are lauded, including several that prevent the government from keeping track of who owns or purchases guns. The RSC also wants to defund red-flag rules that take guns away from domestic abusers, allow concealed carry across state lines, and remove regulations on silencers. The problem of mass shootings is not mentioned.

The report endorses the usual bunch of anti-trans proposals: targeting trans athletes, banning care options, mandating bathroom policies, etc. The section on the border is about what you’d expect: finish Trump’s wall, reinstitute Trump’s cruel and probably illegal treatment of migrants, etc. Some proposals (like hiring more asylum judges to process cases faster) were included in the border proposal Republicans tanked after Trump said he wanted the issue to campaign on. The RSC also wants to reinterpret the 14th Amendment so that it no longer guarantees birthright citizenship, despite what the text actually says.

Healthcare. The RSC wants to return to the bad old days before ObamaCare. The report calls for a “more market-oriented” approach to health insurance, and promises lower premiums by eliminating “ObamaCare mandates”. In other words, you could once again buy junk insurance that doesn’t cost as much but will vanish in a puff of smoke when you actually need it. States would be empowered to define what insurance plans have to cover, and insurance companies could sell across state lines. This would lead to a race-to-the-bottom among states, similar to what we saw with credit card regulation after interstate banking was approved. (There’s a reason why you have to send your payments to South Dakota.) Younger, healthier individuals could get lower-priced policies, taking them out of the insurance pool. The result would be exorbitantly expensive insurance for people who actually need care. The Inflation Reduction Act’s provisions to control drug prices would be repealed. Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program would be “streamlined” by turning them into block grants to the states.

Medicare. The RSC plan to “save” Medicare is essentially a privatization plan, where Medicare mainly provides premium supports for private insurance programs.

This plan ignores one essential fact about private health insurance: Competition between insurance companies does not center on providing better care at lower prices, but on luring healthier clients and discouraging sicker ones. Denying care is a double-win for an insurance company. Not only does the company not pay for the care, but patients who need care will be motivated to find other insurance.

Take cancer, for example. You don’t really know how good your plan’s cancer coverage will be until you get cancer. But at that point you have become an undesirable customer, so the company would rather you switched to some other insurance. Providing the kind of care and service that attracts people with cancer is a bad business model.

Social Security. The report points to the projection that the Social Security Trust Fund will run out of money in 2033, and correctly observes that there are three things to do about that: keep the program running with money from the general fund, raise taxes, or cut benefits. It rejects the first two options and proposes to cut benefits.

Recognizing political dynamite, the RSC refuses to cut current benefits for people already retired. However, Republicans would

- force Congress to vote on cost-of-living increases every year, as opposed to the current system where COLAs are automatic

- lower benefits for future retirees in a means-tested way

- raise the retirement age as life expectancy rises.

None of these benefit cuts are quantified. And, as always, Republicans promise increased revenues from the (mythical) economic growth that their income tax cuts will promote. These days, though, they also add in the economic “growth” that will come from burning more fossil fuels (as long as you don’t have to account for the costs of climate change).

Raising the retirement age as people live longer and are able to work longer makes a certain intuitive sense. But there’s a problem: The gains in lifespan almost entirely benefit wealthier people. Working class and poor people, in general, have had only modest increases in life expectancy in recent decades.

MIT News reported in 2016:

[T]he study shows that in the U.S., the richest 1 percent of men lives 14.6 years longer on average than the poorest 1 percent of men, while among women in those wealth percentiles, the difference is 10.1 years on average.

This eye-opening gap is also growing rapidly: Over roughly the last 15 years, life expectancy increased by 2.34 years for men and 2.91 years for women who are among the top 5 percent of income earners in America, but by just 0.32 and 0.04 years for men and women in the bottom 5 percent of the income tables.

Also, while people who do primarily mental work can easily work into their 70s if they’re so inclined, people who do physical labor often don’t have that option. If you raise their retirement age, they’ll wind up eating cat food.

Budget reform. The RSC proposes a series of “reforms” that would lock the government into conservative priorities, no matter what the voters want. Like a constitutional amendment to cap revenues and force a balanced budget.

This proposal would bar annual spending in excess of 20 percent of GDP and prevent Congress from relying on tax increases to balance the budget, which is key to preserving a dynamic and innovative economy.

This is a seriously bad idea. For example, consider the recent pandemic. In FY 2020 (Trump’s last full year), federal spending was over 30% of GDP. That spending was what allowed Americans to stay home, and prevented many Americans from losing their homes when their jobs disappeared. If the government had been limited to 20% of GDP, Covid would have run wild and probably millions more Americans would have died. Millions of others would have been homeless.

Now start imagining various future climate-change doom scenarios — seas rising, farmlands turning to deserts, and so on. The government would just have to throw up its hands.

And not allowing Congress to raise taxes makes all sorts of policy changes impossible, whether voters want them or not. Republicans wouldn’t have to argue against Medicare for All or the Green New Deal, for example, because both would be constitutionally infeasible.

The RSC also proposes that the reconciliation process not be allowed to increase spending or taxes. In other words, if Republicans get control of the presidency and Congress, they can use reconciliation to pass their priorities (like the Trump tax cuts), but if Democrats get control, they can’t pass theirs (like the Inflation Reduction Act).

Other mandatory spending. There’s a grab-bag of stuff in here, most of which was too in-the-weeds for me to evaluate. However, I did notice the proposals to end student loan forgiveness, auction off the TVA’s non-nuclear assets, revoke the charters of home-loan guaranteeing agencies Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, and reduce the benefits of federal employees.

Non-defense discretionary spending. Another grab-bag of (mostly) cuts. Stop the Forest Service from buying more land. Eliminate anything to do with “the left’s climate agenda”, or any program that can be tarred as “woke”. Eliminate the Consumer Product Safety Commission because it advances “Biden’s radical climate agenda, including attempting to ban gas stoves”. (This whole talking point is a canard. The footnote that supposedly supports it includes a CPSC spokesman saying the commission “isn’t coming for anyone’s gas stoves”.)

The RSC wants to cut funding for the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, not because cybersecurity isn’t a problem, but because CISA is trying to fight disinformation online. The Republican agenda is based on disinformation, so they see this as a threat. Similarly, Republicans want to eliminate Targeted Violence and Terrorism Prevention Grants, because the program doesn’t exempt right-wing terrorist groups. OSHA is targeted for cuts to get revenge for President Biden’s Covid vaccine mandates. Similarly, the US contribution to the World Health Organization is eliminated.

Of course Republicans want to cut funding for the EPA and leave the Paris Climate Accords. Also: stop funding Amtrak and prohibit spending on high-speed rail.

The report calls for eliminating the National Endowment for the Arts, National Endowment for the Humanities, and Corporation for Public Broadcasting, as well as cutting support for the Smithsonian (because the museum complex is too woke).

So there it is: the Republican fantasy world in its full glory. Now you know what you’re voting for if you vote Republican in November.