As I pointed out last week, the Constitution is pretty clear about what should happen now: President Obama should nominate a replacement and the Senate should either approve or disapprove of the nominee’s ability to handle the job. (Article II, Section 2 says “he shall nominate”. The shall indicates a duty, rather than may, which would offer an option.)

Retired Justice Sandra Day O’Connor (appointed by President Reagan) sees it that way. Asked whether the process should wait until we have a new president, she said: “I don’t agree. I think we need somebody there now to do the job, and let’s get on with it.”

When Alexander Hamilton defended the Constitution’s appointment process in Federalist #76, he expected the Senate to examine an individual nominee’s character and ability, but never considered the possibility that the Senate might engage in the kind of blanket obstruction Republicans are proposing.

But might not [the president’s] nomination be overruled? I grant it might, yet this could only be to make place for another nomination by himself. The person ultimately appointed must be the object of his preference, though perhaps not in the first degree. It is also not very probable that his nomination would often be overruled. The Senate could not be tempted, by the preference they might feel to another, to reject the one proposed; because they could not assure themselves, that the person they might wish would be brought forward by a second or by any subsequent nomination. They could not even be certain, that a future nomination would present a candidate in any degree more acceptable to them; and as their dissent might cast a kind of stigma upon the individual rejected, and might have the appearance of a reflection upon the judgment of the chief magistrate, it is not likely that their sanction would often be refused, where there were not special and strong reasons for the refusal.

But, as I have often pointed out before, republics don’t run just on their rules, but also on their norms and mores. So it’s legitimate to wonder whether there might be some long-standing gentlemen’s agreement or common courtesy that would prevent Obama from nominating Scalia’s replacement. The answer is pretty clearly no. Republicans have been claiming all sorts of unwritten rules to that effect, all of which resemble the rules of Calvinball.

It is true that there have not been a lot of election-year Supreme Court vacancies. (I assume justices see an election year as an inconvenient time to retire, though I don’t really know.) The closest recent example is the vacancy filled by Justice Kennedy: Justice Lewis Powell retired in June, 1987, and Kennedy was not confirmed until February, 1988 — President Reagan’s last year in office. (The delay was caused by the Senate’s refusal to confirm Robert Bork, and then by the withdrawal of Reagan’s second nominee.)

It is true that there have not been a lot of election-year Supreme Court vacancies. (I assume justices see an election year as an inconvenient time to retire, though I don’t really know.) The closest recent example is the vacancy filled by Justice Kennedy: Justice Lewis Powell retired in June, 1987, and Kennedy was not confirmed until February, 1988 — President Reagan’s last year in office. (The delay was caused by the Senate’s refusal to confirm Robert Bork, and then by the withdrawal of Reagan’s second nominee.)

If you go further back, you get clearer parallels: Presidents Taft, Hoover, and Franklin Roosevelt nominated justices in election years and got them confirmed. Wilson got two justices confirmed in 1916. Eisenhower (1956) and Johnson (1968) failed to get their election-year picks confirmed but (according to Amy Howe of SCOTUSblog) “neither reflects a practice of leaving a seat open on the Supreme Court until after the election.” In Eisenhower’s case, the Senate was already adjourned for the fall campaign (so he made a recess appointment). Johnson’s pick was the target of a bipartisan filibuster, having to do with the nominee’s ethical issues.

No one has come up with an example that supports the Republican position: a Supreme Court seat that was left open for a year to allow the next president to fill it. That would be unprecedented in the last 150 years.

There is also no unwritten rule saying that a new justice should fill the same ideological role as the justice s/he replaces. Arch-conservative Clarence Thomas, for example, replaced one of the Court’s most liberal judges, Thurgood Marshall.

There is also no unwritten rule saying that a new justice should fill the same ideological role as the justice s/he replaces. Arch-conservative Clarence Thomas, for example, replaced one of the Court’s most liberal judges, Thurgood Marshall.

It’s worth pointing out that even if any of these unwritten rules really existed, Senate Republicans are in a poor position to claim them. Throughout the Obama administration, they have blasted through the previous norms and mores of Senate behavior: making the filibuster routine; blocking nominees not for individual reasons, but in order to screw up the organizations they were supposed to head; brinksmanship with the debt ceiling; and many other examples. They have consistently refused to be bound by any unwritten rules of courtesy, so why should they get the advantage of one now?

There have been several attempts to claim hypocrisy on the part of Democrats who want to follow the constitutional process. One frequently cited example is a 2007 quote from Chuck Schumer to the effect that the Democratic Senate “should not confirm any Bush nominee to the Supreme Court except in extraordinary circumstances.”

Two things stand out about that: First, no more vacancies came up during Bush’s term, so we don’t know to what extent Schumer (who was just an ordinary senator at that time, and spoke only for himself) was just posturing in front of a liberal audience. (If today’s Republicans posture about blocking all nominees, but then go ahead and do their constitutional duty anyway, that would be fine.) Second, the quote is plucked out of its context, as Josh Marshall explains (with video of Schumer’s remarks):

What Schumer actually said was that Senate Democrats had been hoodwinked by President Bush’s first two Supreme Court picks – Roberts and Alito. They’d accepted assurances that they were mainstream conservative judges who would operate within the precedents and decisions of the Rehnquist Court but hadn’t. (Certainly, the experience since 2007 has more than ratified this perception.) Schumer said Democrats should try to block any future Bush nominees unless they could prove that they were ‘in the mainstream’ and would abide by precedent. …

Schumer quite explicitly never said that the Bush shouldn’t get any more nominations. He also didn’t say that any nominee should be rejected. He said they should insist on proof based on judicial history, rather than just promises that they were mainstream conservatives rather than conservative activists, which both have proven to be. But again, set all this aside. He clearly spoke of holding hearings and being willing to confirm Bush nominees if they met reasonable criteria.

Another attempt is to cite a 1960 sense-of-the-Senate resolution which the conservative American Thinker blog characterizes as “against election-year Supreme Court appointments”.

Except that’s not what it says. The resolution opposed recess appointments to the Supreme Court, which put a justice on the Court temporarily without Senate approval, not election-year appointments. Since Obama is not making a recess appointment — Republicans having fought tooth-and-nail to limit Obama’s recess-appointment power — the 1960 resolution has no connection to the current situation.

A tweet from Ken Wissonker puts a different slant on the wait-for-the-next-president idea:

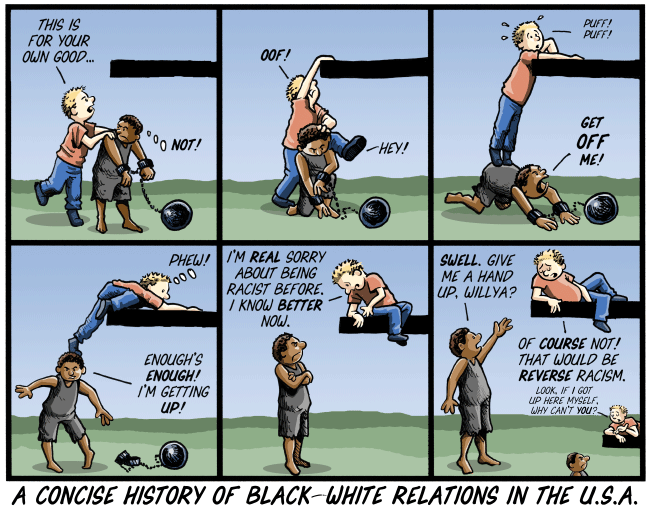

As a friend put it: “Apparently, the GOP thinks that Black Presidents only get 3/5ths a term.”

The attempt to imply that Obama’s nominee will somehow be illegitimate is part of the larger effort to de-legitimize Obama’s entire presidency. And it’s hard to escape the conclusion that race has played a role in this project.

From the beginning, his opponents have never granted Obama the respect due a president of the United States. Whether it’s shouting “You lie!” during the State of the Union, or encouraging members of military to refuse orders, or spreading baseless rumors about his birth or religion, or complaining whenever he does things all presidents do, or expressing frustration that impeachment requires evidence, or warning foreign leaders not to make agreements with him — the consistent message has been that Barack Obama is not a legitimate president of the United States.

So we elect our first black president, and he’s treated with less respect than all previous presidents. Who could have guessed?

Thursday, the story of the Kentucky county clerk who refused to issue marriage licenses (now that same-sex couples can marry) reached its inevitable conclusion. Having been

Thursday, the story of the Kentucky county clerk who refused to issue marriage licenses (now that same-sex couples can marry) reached its inevitable conclusion. Having been

But the way the new “religious freedom” will ultimately be brought down is to force courts to consider its laws in the light of the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of “equal protection under the law”. If “religious freedom” laws end up giving atheists and Muslims the same consideration Christians are claiming, Christians will repeal those laws themselves.

But the way the new “religious freedom” will ultimately be brought down is to force courts to consider its laws in the light of the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of “equal protection under the law”. If “religious freedom” laws end up giving atheists and Muslims the same consideration Christians are claiming, Christians will repeal those laws themselves.