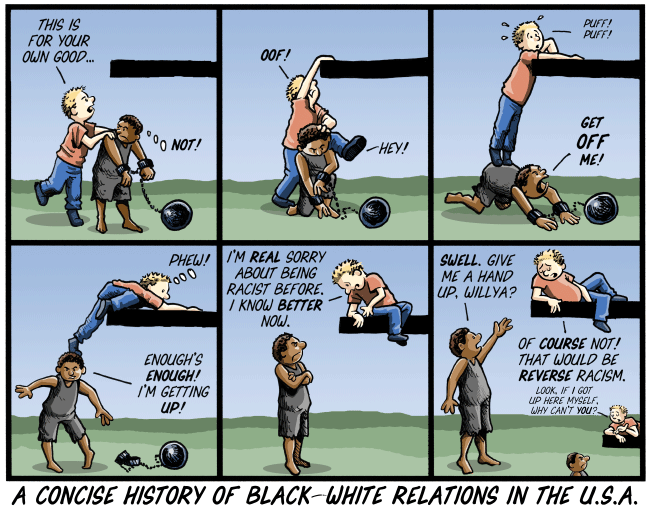

The Court has decided to trust majority rule to defend minority rights. That didn’t work very well the last time.

The Court has decided to trust majority rule to defend minority rights. That didn’t work very well the last time.

It’s hard to appreciate this week’s Supreme Court decision on affirmative action without knowing about a case from the 19th century.

The Civil Rights Cases. In 1883, just a few years after Union troops stopped occupying the states of the former Confederacy, the Supreme Court ruled on five cases it combined into the Civil Rights Cases (Wikipedia, text of decision). Eight justices ruled unconstitutional the Civil Rights Act of 1875, which banned racial discrimination in “accommodations, advantages, facilities, and privileges of inns, public conveyances on land or water, theaters, and other places of public amusement”. The Court said that Congress had overstepped its power, because the 13th and 14th Amendments only gave it “corrective” power to reverse state laws that denied blacks their civil rights. Congress couldn’t legislate directly to guarantee those rights.

And then the Court went on to make a more sweeping statement:

When a man has emerged from slavery, and, by the aid of beneficent legislation, has shaken off the inseparable concomitants of that state, there must be some stage in the progress of his elevation when he takes the rank of a mere citizen and ceases to be the special favorite of the laws, and when his rights as a citizen or a man are to be protected in the ordinary modes by which other men’s rights are protected.

In other words, if the former slaves needed this kind of protection, they should seek it from their state governments, the way white people would. No doubt that sounded very reasonable to most whites, even most Northern white liberals: Slavery was over; the former slaves were citizens now; they should avail themselves of the protections the law had made for other citizens.

But Douglas Blackmon observed in Slavery By Another Name that things didn’t quite work out that way.

Civil rights was a local, not federal issue, the Court found. The effect was to open the floodgates for laws throughout the South specifically aimed at eliminating those new rights for former slaves and their descendents. … [A] declaration by the country’s highest courts that the federal government could not force states to comply with the constitutional requirement of the equal treatment of citizens, regardless of race, opened a torrent of repression.

As reasonable as it may have sounded at the time, from the perspective of history the Civil Rights Cases decision was the opening bell for the Jim Crow era. Due process and equal protection under the laws had become pro forma rights; if a state preserved certain outward appearances, it need not provide any real equality. Or, more accurately, the state continued to have a moral obligation to provide equality, but the federal government had no authority to enforce that obligation. The lone dissent of Justice John Harlan (not to be confused with his grandson, John Harlan II, a 20th-century Supreme Court justice whose opinions figure as precedents in this week’s ruling) was prophetic:

[I]f the recent amendments are so construed … we shall enter upon an era of constitutional law when the rights of freedom and American citizenship cannot receive from the nation that efficient protection which heretofore was unhesitatingly accorded to slavery and the rights of the master.

Harlan also was the lone dissent in the 1896 Plessy v Ferguson decision that enshrined separate-but-equal. He deserves to be more famous than he is.

Michigan. Now let’s talk about this week’s decision, Schuette v Coalition to Defend Affirmative Action. Like most race cases these days, there has been a back-and-forth that makes the underlying principles hard to sort out: Until 2003, the University of Michigan used race as a consideration for admission to both its undergraduate program and its law school. That year, the Supreme Court ruled on both: It threw out the undergraduate system in the Gratz decision but upheld the law school system in Grutter.

Both cases hung on the same issues, and Justices O’Connor and Breyer were the swing votes. Previous cases had identified only one interest that could justify affirmative action by a state university: the overall educational advantage provided by a diverse student body. In other words, the state couldn’t favor one race for the simple purpose of giving that race an advantage, but it could decide that a diverse student body provides a better education for everyone. (Imagine studying the Civil War in an all-white classroom versus a classroom where other races are represented. Probably the discussions would be very different, and a university might legitimately decide that the mixed-race classroom experience is better.) But the Court insisted that the particular plan to promote diversity had to be narrowly tailored for that purpose, rather than resembling a racial quota system. The law-school plan passed muster under the narrowly-tailored standard; the undergraduate plan didn’t.

But Michigan’s anti-affirmative-action groups weren’t satisfied with a split decision, so in 2006 (as a direct response to Grutter), a referendum added an amendment to the Michigan Constitution banning “preferential treatment to any individual or group on the basis of race, sex, color, ethnicity, or national origin” in education, hiring, or contracting by the state or any public institution under the authority of the state. Overall, the amendment passed with a clear 58%-42% majority, but the exit poll showed major demographic splits: White men voted for it 70%-30%, while non-white women opposed it 82%-18%. If you work out the numbers, the entire margin of victory came from white men (42% of the electorate), while everyone else split almost evenly.

So you wind up with two separate levels of dispute: affirmative action itself, but also the limits of democracy. In other words, if the majority doesn’t get its way for some reason, under what circumstances can it change the rules?

The Political Process doctrine. The history of the Civil Rights movement since 1883 has been a story of the white majority changing the rules whenever the black minority seemed about to rectify some disadvantage. If the 15th Amendment gave blacks the right to vote, poll taxes and literacy tests could take it away, while grandfather clauses protected poor or illiterate whites from disenfranchisement. If Arkansas couldn’t keep blacks out of Little Rock’s Central High, the governor could shut the school down. Slavery By Another Name is about how Southern whites circumvented the elimination of slavery itself by inventing bogus crimes that blacks could be convicted of and then sentenced to hard labor.

The Supreme Court cases on race — from the Civil Rights Cases to Brown and beyond into enforcing Brown‘s requirement of integrated schools — revolve around the Court’s increasing realization that it couldn’t deal with state and local governments under the assumption of good faith. The white majority simply did not want blacks to receive due process and equal protection under the laws, and any high principles announced by the Court would be examined for loopholes rather than implemented.

As a result, the Court evolved what came to be called the Political Process doctrine: If a minority achieves one of its goals through the ordinary decision-making process — courts, school boards, elections, etc. — and the majority responds by changing the rules to move the decision to a different body where the minority will lose, that rule-change deserves special scrutiny from the courts. If there was no compelling reason to change the process beyond frustrating the minority, the change is invalid.

Justices Sotomayor, Ginsberg, Scalia, and Thomas all agree that the Political Process doctrine applies to this case. Sotomayor and Ginsberg want to invoke it to invalidate the Michigan constitutional amendment, while Scalia and Thomas want to take this opportunity to reverse the doctrine entirely. The plurality opinion (written by Justice Kennedy, and joined by Roberts and Alito), is another example of something I complained about two weeks ago: covertly reversing decisions without appearing to do so. After Schuette, the Political Process doctrine is dead. While it remains as a precedent, it’s hard to imagine a situation where it could be invoked.

And that development has consequences beyond affirmative action.

The opinions. The plurality opinion (representing Kennedy, Roberts, and Alito) was written by Justice Kennedy. If you’ve been reading the Sift since last summer, you know I don’t think much of Justice Kennedy’s writing style and the muddled mind it seems to represent. (Lower court judges seem not to know how to apply Kennedy’s rulings, which tells you something.) I suspect that’s why the Chief Justice chose Kennedy to write this opinion rather than doing it himself. Any judge who tries to invoke the Political Process doctrine in the future will have to glean some principles of application from Kennedy’s opinion; probably they will just throw up their hands and decide the case on some other basis.

Kennedy reminds us that “It cannot be entertained as a serious proposition that all individuals of the same race think alike”, that there are no clear legal standards for determining the interests of a racial group, or even of defining who is in or out of the group, and so on. If the Court allows that there are racial interests that prevent rule changes, race might be dragged into any number of issues in order to freeze the process in place.

In short, if racial majorities decide to act in bad faith, judges are simply not clever enough to catch them. Kennedy concludes:

Democracy does not presume that some subjects are either too divisive or too profound for public debate.

as if anyone had ever made that claim.

Scalia’s dissent (joined by Thomas) is painful to read, because as he gets older, Scalia is less and less able to pretend that he respects anyone who disagrees with him. So his opinions increasingly contain more attitude than law. But at least he does go through the relevant precedents, explaining why they were all wrongly decided. I would love to hear Justice Scalia’s opinion on the Civil Rights Cases, or whether rule changes that disadvantage a minority should ever be thrown out by the Court. Most of all, I want to hear how he will square all this with what he rules in the upcoming Hobby Lobby case, where the minority seeking protection is abortion-opposing Christian employers.

Justice Breyer’s concurrence shows more honest inner conflict than any of the others. He wants to support both the democratic process and minority rights, but has to come down on the side of democratic process.

the principle that underlies [the Political Process doctrine precedents] runs up against a competing principle, discussed above. This competing principle favors decisionmaking through the democratic process. Just as this principle strongly supports the right of the people, or their elected representatives, to adopt race-conscious policies for reasons of inclusion, so must it give them the right to vote not to do so.

Justice Sotomayor’s dissent (joined by Ginsberg) is as long as all the rest put together, probably because she alone is arguing that the Court needs to pay attention to nuance. Like Scalia, she takes the precedents seriously, but she wants to apply those precedents rather than reverse them. She also thinks the Court needs to consider where the Michigan constitutional amendment fits in the long history of changing the rules to short-circuit minority victories.

As a result of [the amendment], there are now two very different processes through which a Michigan citizen is permitted to influence the admissions policies of the State’s universities: one for persons interested in race-sensitive admissions policies and one for everyone else. A citizen who is a University of Michigan alumnus, for instance, can advocate for an admissions policy that considers an applicant’s legacy status by meeting individually with members of the Board of Regents to convince them of her views, by joining with other legacy parents to lobby the Board, or by voting for and supporting Board candidates who share her position. The same options are available to a citizen who wants the Board to adopt admissions policies that consider athleticism, geography, area of study, and so on. The one and only policy a Michigan citizen may not seek through this long-established process is a race-sensitive admissions policy that considers race in an individualized manner when it is clear that race-neutral alternatives are not adequate to achieve diversity. For that policy alone, the citizens of Michigan must undertake the daunting task of amending the State Constitution.

But that point of view lost. As in last summer’s Voting Rights decision (in which Chief Justice Roberts announced the profound legal principle that “things have changed”) the history of racism and racial progress in America is not considered relevant by the Roberts Court. Going forward, the Court appears ready to assume good faith on the part of the white majority. Let’s hope it works out better this time.

Comments

Reblogged this on jerihammondblog and commented:

Good explanation!

Trackbacks

[…] week’s featured articles are “More Than Just Affirmative Action” and “Cliven Bundy and the Klan Komplex“. Both topics sent me back to study the […]

[…] the usual 5 against the usual 4) in Greece v Galloway follows the same pattern we saw in the affirmative action case two weeks ago: If you’re in the majority and you want to lord it over the minority, the Court […]

[…] fixing it. In order to understand where Coates is coming from, you need to appreciate where we are: The Supreme Court believes that any government action for the specific purpose of benefiting blacks (or any racial […]

[…] year I explained the Supreme Court’s Hobby Lobby decision, the Schuette decision about affirmative action, and the McCutcheon decision on campaign finance, plus lower-court decisions involving net […]