In an increasingly unequal society, it’s very soothing for the winners to hear that they’re the “real” victims.

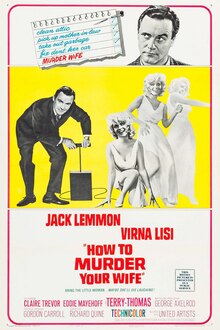

In the film “How to Murder Your Wife“, Jack Lemmon’s character is innocent — in reality his wife isn’t dead at all — but as his trial progresses the evidence against him becomes so convincing that he decides to try a risky strategy: Confess, and make a closing argument that appeals to the self-interest of his all-male jury. Think how great it would be if women knew we could kill them!

In the film “How to Murder Your Wife“, Jack Lemmon’s character is innocent — in reality his wife isn’t dead at all — but as his trial progresses the evidence against him becomes so convincing that he decides to try a risky strategy: Confess, and make a closing argument that appeals to the self-interest of his all-male jury. Think how great it would be if women knew we could kill them!

If one man – just one man – can stick his wife in the goop from the gloppitta-gloppitta machine, and get away with it! Whoa-ho-ho, boy, we’ve got it made. We have got it made. All of us.

The men vote to acquit. (Then Lemmon’s wife turns up and there is a happy ending.)

In 1965, that was comedy: Men feel henpecked, so the fantasy of regaining respect by making women fear for their lives has enough appeal to be worth joking about.

Forty-three years later, the closing argument in the Brett Kavanaugh nomination was a strangely inverted version of Lemmon’s: If just one woman can stop a man from going to the Supreme Court by accusing him of sexual assault, then we’re finished. All of us.

President Trump made the argument like this:

I say that it’s a very scary time for young men in America when you can be guilty of something that you may not be guilty of. This is a very difficult time. What’s happening here has much more to do than even the appointment of a Supreme Court Justice.

Asked what his message for young women was, Trump said “Women are doing great.”

He was echoing something his son, Don Jr., had said in an interview with Britain’s Daily Mail TV: He’s more afraid for his sons than his daughters:

I’ve got boys, and I’ve got girls. And when I see what’s going on right now, it’s scary.

Glenn Beck warned:

If the Democrats cram this down, I believe Americans will rise up at the polls, as we don’t want this to happen to our sons, brothers, husbands fathers.

“This”, apparently, is to pay some tangible price because a woman makes a false accusation against you. Many people making this argument don’t even claim that Christine Blasey Ford is lying about Kavanaugh. Even if she’s telling the truth, they say, she has little in the way of supporting evidence. And if just one woman can make a man pay a price purely on the strength of her testimony … then we’re finished, all of us.

The reverse-handmaid dystopia. Something strange is going on here, and it speaks to the roots of the conservative mindset: There is a fantasy dystopia that they can imagine we might be moving towards, and the fear of that dystopia outweighs reams and reams of actual injustice in the here and now.

In the dystopia, the reverse-Handmaid’s-Tale world, any woman can inflict dire consequences on any man just by making up an accusation against him. She will be believed and he won’t, so he’ll be “guilty until proven innocent“, as Mitch McConnell puts it. Every man will be forced to live in fear that a false accusation will suddenly “ruin his life“.

There are a number of weird things about this thought process:

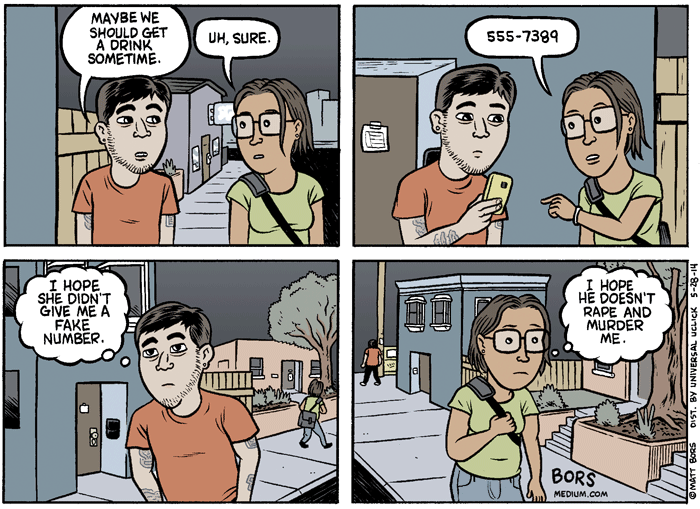

- Women live in fear now. Not fear of some imagined future damage to their reputations or career prospects, but of actual physical attacks that are happening every day.

- False accusations already can be made against anyone for almost anything; sexual assault is not special in that way. So Hillary Clinton supposedly murdered Vince Foster and was also involved in a child sex ring hidden under a pizza restaurant. Barrack Obama, according to then-citizen Donald Trump, was a Kenyan Muslim who ascended to the presidency by fraud. Somehow, these well known recent examples of false accusations don’t cause us all to live in terror.

- Black men actually lived in such a dystopia for centuries: If a white woman accused him of sexual impropriety (which could be little more than a lecherous glance), just about any black man could be lynched.

But the weirdest thing is the idea that society will suddenly flip from one extreme to the other, without ever occupying the reasonable ground in between. Right now, a woman’s report of sexual assault is often disbelieved, and is rarely seen as sufficient reason to impose any consequences at all on the reported attacker. It’s not just that you can go to the Supreme Court if one (or three) women accuse you, you can be elected president if more than a dozen women accuse you. If your rapist is viewed as a promising young white man from a good family, even a conviction might only result in a light sentence.

Perversely, the fact that women’s accounts of sexual assault so rarely lead to any serious consequences (except negative ones for the woman) is precisely the reason to believe them: Christine Blasey Ford went into the Kavanaugh hearings expecting to achieve nothing and knowing that her own life would be disrupted. That’s the typical situation these days. By far, the most likely explanation of why she would put herself through this ordeal is that Kavanaugh actually assaulted her.

False accusations are not impossible, but they are not common. False-accusation worriers still bring up the Duke lacrosse team case. But that was a dozen years ago. That’s still the standard example because false accusations that lead to punishments are so rare.

What’s the reasonable middle? If we ever got to a point where men could be jailed just on one woman’s say-so, the situation I just described wouldn’t hold any more: Women would have motive to make stories up, just as Mike Flynn’s son was motivated to promote false stories about PizzaGate, or Donald Trump Jr. to make false claims about Anderson Cooper.

Ideally, we could get to a point where sexual-assault accusations could be treated like other accusations: Absurd ones could be discounted, but plausible ones would be investigated, with the investigation becoming more serious as lighter investigations failed to disprove them. Different levels of plausibility would lead to different consequences: Proof beyond reasonable doubt would continue to be the standard for taking away someone’s liberty, but lesser standards would hold for lesser consequences.

That’s how things are now for non-sexual charges. Suppose your colleagues at work believe you’ve been stealing money out of their desks. If they have proof beyond reasonable doubt, you might go to jail. If they don’t, but a preponderance of evidence points to your guilt, your boss might agree with them and fire you. If your guilt or innocence is hard to determine, you might keep your job, but when a better job opens up that requires more trust, you might miss out.

As long as Donald Trump is president and Brett Kavanaugh has a lifetime appointment to our highest court, we’re not in that reasonable middle. We’re clearly not treating sexual assault charges like other charges.

Other conservative fantasies that overpower actual events. The male-threatening dystopia follows a common pattern on the right: a particularly worrisome fantasy or unique example often outweighs far more common real events.

So the fantasy that men will hang around in women’s bathrooms falsely claiming to be transsexual, and then assault women there — has that ever actually happened? But on the right, that imagined horror outweighs the actual problems of transsexuals, like the middle school student in Stafford County, Virginia who was left on the bleachers during an active-shooter drill and eventually told to sit in the hall between the boys’ and girls’ locker rooms, because school officials couldn’t decide which one she should shelter in. (In essence, the school practiced letting the shooter kill her.) That happened last week, not a dozen years ago.

If you want to discuss limits on the size of gun magazines (which would save actual lives, because mass shooters are most commonly stopped when they have to reload), you’ll be met with fantasies of home invasions in which ten bullets (or any finite number) just aren’t enough. Even the most reasonable and toothless gun control proposal will invoke fantasies of a tyrannical government herding its disarmed populace into concentration camps. (Strangely, this doesn’t happen in Japan, or in any other democratic country with very few civilian guns.)

The reversal of victimhood. The person who best expressed what this is all about this week was Trevor Noah of The Daily Show.

“Trump’s most powerful tool,” Noah says, is that he knows how to wield victimhood. He knows how to offer victimhood to people who have the least claim to it.”

If you belong to a privileged group, quite possibly at some level you feel guilty about that. Or maybe you just feel vulnerable to the charge that you don’t deserve what you have, or that other people who deserve more actually have less. Although you try not to think about it, you may vaguely wonder if somewhere innocent people are being mistreated in your name.

So it’s very powerful when a demagogue like Trump can tell you that you are “the real victim”. He allows you to project your guilty feelings onto someone else, and instead to claim the moral righteousness of victimhood. Noah explains:

It’s not that we have to be feeling sorry for women, but women are the victims and that’s what we’re trying to fix. But Trump has managed to turn that, and he’s turned it with everybody. He goes: “The real victims in this story is not the kids in the cages, it’s you. It’s you who … they’re coming to take your place. The real victim isn’t the refugee from Syria, it’s you, who’s going to get blown up by a terrorist bomb.”

… People felt, because of Trump, like they were losing their country. They felt like America was losing. And feeling is oftentimes more powerful than what is actually happening.

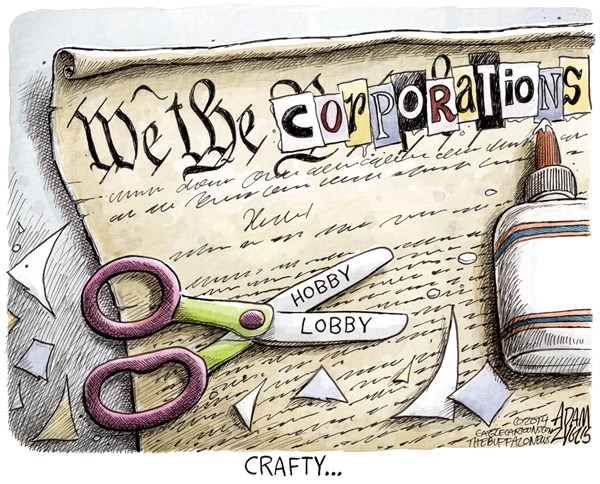

So we wind up in the situation I described years ago in “The Distress of the Privileged“: Whites think they are the real victims of racism. Christians think their religious freedom is under attack, and needs the government’s defense. Anglos are being victimized by Hispanic immigrants who do our dirty work for almost no money. Rich people are being “punished” by taxes — even taxes far lower than rich people used to pay.

And men can still, with a great deal of impunity, harass women. It’s embarrassing when they start to complain about it, but that embarrassment doesn’t make us the victims. Dr. Blasey Ford has her memories, both of being attacked decades ago, and of being vilified in front of a cheering crowd by the President of the United States. Meanwhile, Justice Kavanaugh has the job he has wanted all his life. He is not the victim.

We live a nation that is becoming increasingly unequal, that is ever-more-harshly divided between winners and losers. If you are a winner with any semblance of a conscience, you probably are uneasy about that, whether you think about it consciously or not. It’s very soothing to be told that the situation is exactly the reverse of how it appears, that you, the winner, are the “real” victim.

It’s soothing, but it’s false. And the more we indulge in this kind of thinking, the more unjust our society will be.

For contrast, look at the two men Clinton has run against — Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders. Both men have unusual hair. Both take some ribbing for it, but it’s really not a big deal. (Clinton could never have turned a bad-hair day into a t-shirt, as Bernie did.) I doubt that either of their campaigns wasted a single minute of meeting time discussing “What are we going to do about his hair?”

For contrast, look at the two men Clinton has run against — Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders. Both men have unusual hair. Both take some ribbing for it, but it’s really not a big deal. (Clinton could never have turned a bad-hair day into a t-shirt, as Bernie did.) I doubt that either of their campaigns wasted a single minute of meeting time discussing “What are we going to do about his hair?”