Daniel Sharfstein tells the story of three families who crossed the color line, and their descendents who forgot.

One of Dave Chappelle’s most memorable bits is his portrayal of Clayton Bigsby, a blind white supremacist who doesn’t know he’s black. Bigsby writes racist books whose readers also think he’s white. He lives in a remote area with few neighbors, and only appears in public in his KKK hood. A few white supremacist friends know the truth, but they keep the secret because “He’s too important to the movement.”

One of Dave Chappelle’s most memorable bits is his portrayal of Clayton Bigsby, a blind white supremacist who doesn’t know he’s black. Bigsby writes racist books whose readers also think he’s white. He lives in a remote area with few neighbors, and only appears in public in his KKK hood. A few white supremacist friends know the truth, but they keep the secret because “He’s too important to the movement.”

Bigsby is an exaggerated version of Mr. Oreo, a character created as a thought experiment by philosopher Charles W. Mills of Northwestern. Mr. Oreo was born to parents who identified as black and he appears black himself, but he has always thought of himself and described himself as white. At some point he goes through a medical process that alters his features, hair, and skin color so that he becomes indistinguishable from whites. Is he white? Or is there an unalterable underlying reality to his blackness?

According to professors who have discussed Mr. Oreo in class, students almost unanimously judge Mr. Oreo to be black. As David Livingston Smith explains in Less Than Human (his fascinating book on dehumanization, which devotes a lot of time to the belief that certain races are subhuman), our culture commonly believes that some personal traits are changeable (a weak man can go through a muscle-building process to become a strong man) while others, like race, are not.

According to professors who have discussed Mr. Oreo in class, students almost unanimously judge Mr. Oreo to be black. As David Livingston Smith explains in Less Than Human (his fascinating book on dehumanization, which devotes a lot of time to the belief that certain races are subhuman), our culture commonly believes that some personal traits are changeable (a weak man can go through a muscle-building process to become a strong man) while others, like race, are not.

We tend to think — perhaps in spite of ourselves — that black people constitute a natural kind, whereas weak people don’t. … We say a person has large muscles, but we say they are of a certain race. … A person can gain or lose muscle while remaining the same person, but we tend to think that if they were to change their race, it would amount to becoming an entirely different person.

Real life provides its own examples, some even more compelling than Mr. Oreo. In her 1949 autobiographical essay collection Killers of the Dream, Lillian Smith recalls Janie, a white-skinned little girl taken from a poor black family newly arrived in the colored part of town. (They “must have kidnapped her”, the local whites decided.) Janie was brought to live with the Smiths, and Lillian fell into a big-sister role.

Real life provides its own examples, some even more compelling than Mr. Oreo. In her 1949 autobiographical essay collection Killers of the Dream, Lillian Smith recalls Janie, a white-skinned little girl taken from a poor black family newly arrived in the colored part of town. (They “must have kidnapped her”, the local whites decided.) Janie was brought to live with the Smiths, and Lillian fell into a big-sister role.

It was easy for one more to fit into our ample household and Janie was soon at home there. She roomed with me, sat next to me at the table; I found Bible verses for her to say at breakfast; she wore my clothes, played with my dolls, and followed me around from morning to night.

But in a few weeks, word came from a distant colored orphanage: Janie only appeared to be white; she was “really” black and had to return to the black family who had adopted her. At first, Lillian could not see the sense in this, but eventually she yielded to superior adult wisdom.

I was overcome with guilt. For three weeks I had done things that white children are not supposed to do. And now I knew these things had been wrong.

In The Invisible Line: a secret history of race in America, Daniel J. Sharfstein tells a more elaborate and challenging story, one that “has been hiding in plain sight” for centuries. He describes it as a “hidden migration”:

African Americans began to migrate from black to white as soon as slaves arrived on the American shore. This centuries-long migration fundamentally challenges how Americans have understood and experienced race, yet it is a history that is largely forgotten.

In earlier eras historians have acknowledged the passing-for-white phenomenon, but considered it virtually untraceable. After all, anyone motivated to pass for white was even more motivated to hide the evidence. But the genealogy boom (empowered by easy access to records over the internet and the possibility of analyzing your DNA for information about your ancestors) has unleashed thousands of amateur investigators and turned up many new cases. Lots of Americans are not as white as they think they are, and some are starting to find out.

Sharfstein traces three families who crossed the color line at different points in American history.

The Gibsons. Prior to Bacon’s Rebellion of 1676, race was not nearly as significant in Virginia as it later became. White indentured servants had more in common with the black slaves than with their upper-class masters, and mixed-race children were not unusual. The law classed a child as belonging to the same race as its mother. Gibby and Hubbard Gibson were mixed-race children of a white mother, and so were free. They moved inland, cleared land, and intermarried with the other frontier property-owning families.

As racial standards tightened generation-by-generation, the Gibsons stayed just on the favored side of the color line, and just far enough away from the race-conscious coastal cities that few cared enough to make an issue of their darker-than-average skin. They moved to North Carolina, and then to the wild western side of South Carolina. By the time they reached Kentucky and Louisiana in the 1800s, no one remembered that the family’s race had ever been an issue.

Gibson boys became officers in the Confederate Army, and Yale-educated Senator Randall Gibson of Louisiana played a key role in the negotiations that resolved the contested 1876 presidential election by trading Southern electoral votes for President Hayes’ promise to end Reconstruction. Randall also was a major player in the founding of Tulane University, convincing Paul Tulane to revise his bequest from “serve young men in the City of New Orleans” to “serve young white men in the City of New Orleans”.

A later generation married into the Marshall Field family of Chicago. As curator of the Field Museum of Natural History, Henry Field commissioned a series of sculptures illustrating over a hundred separate “races” for the Hall of Races of Mankind that opened in 1933. He had no clue he was anything but 100% European.

If anyone out there has media connections, I think The Gibsons would make a fabulous miniseries.

The Walls. Stephen Wall was a North Carolina plantation owner who never married, but fathered several children with his female slaves. In the 1830s he appeared to be selling his children to a plantation in Alabama, but in fact this was a ruse. Instead, a family friend delivered the Wall children to a Quaker settlement in Indiana, where Stephen provided resources for them to be raised and educated.

One of those children, O.S.B. Wall, was instrumental in convincing the Ohio governor to field a black regiment in the Civil War. He recruited black soldiers across the state and became a captain, though he arrived at the front too late to see combat. After the war, Wall moved to Washington, D.C., where he became part of a budding freedman aristocracy and held several positions in the local political machine.

But D. C. became one of the first places to disenfranchise blacks after the war. When the city ran into financial difficulties in the Panic of 1873, the federal government took direct authority over local affairs, shunting local elected officials aside for decades. When Democrats (who at the time openly identified themselves as “the white man’s party”) came to power with Grover Cleveland in 1884, white supremacy followed.

Captain Wall married a light-skinned woman, and his children found that they were frequently mistaken for white. His son Stephen married a white woman, but continued to identify as the son of a prominent leader in the black community, for all the good it did him. He was repeatedly let go from his job in the government printing office without cause, only to be rehired later. The final straw came when his indistinguishable-from-white daughter was barred from the public school in his suburban neighborhood, and he lost a series of court cases to have her reinstated, despite being legally in the right. (By prevailing definitions, Isabel’s black ancestry was sufficiently diluted that she should have been considered white. But whatever the text said, the spirit of the law was to protect white families from “falling” into the black community due to the discovery of an unexpected dark ancestor, not to allow a Negro man to marry a white woman and launch his children into white society.)

The family moved, changed its name to Gates, and began passing for white. Two generations later, Thomas Murphy (a “white” Georgian with considerable prejudice against blacks) got a nasty shock from his genealogy research. “You can’t call me a racist because I is one of you,” he told his black co-workers at the Atlanta airport.

The Spencers. Freed slaves had a hard time finding a place for themselves. Slave-owners viewed freedom as a contagious notion, so they didn’t want the freedmen around, and no state wanted to advertise itself as a destination for other states’ former slaves. For many, the solution was to go someplace without a lot of neighbors.

George Freeman and Jordan Spencer (who might been his son) were mixed-race freed slaves (of the white Spencer family) who settled in the hill country of eastern Kentucky in the early 1800s. They married sisters from a white family that passed through and left their daughters behind. When they ran into legal trouble from the local whites, Freeman stayed and hired a lawyer, but Spencer moved deeper into the wilderness. After he arrived in Johnson County, Kentucky, he didn’t exactly proclaim himself a white man, but he just started acting like one. White men, for example, were required to muster with the local militia and drill, while black men were forbidden to have weapons. Spencer showed up for drills, and nobody took it on themselves to tell him he shouldn’t.

At the time, even the South Carolina Supreme Court was recognizing the extent to which race was socially constructed. In an 1835 case, Justice William Harper wrote:

The condition of the individual is not to be determined solely by the distinct and visible mixture of negro blood, but by reputation, by his reception into society, and his having commonly exercised the privileges of a white man. But his admission to these privileges, regulated by the public opinion of the community in which he lives, will very much depend on his own character and conduct; and it may be well and proper, that a man of worth, honesty, industry, and respectability, should have the rank of a white man, while a vagabond of the same degree of blood should be confined to the inferior caste.

The hill country was more focused on clans than on races, and over time the Spencers became just another clan, darker than most, but respectable in their way. Jordan’s children intermarried with other clans — some of whom were not too clear about their own ancestry — who then found it convenient to describe the Spencers as white, if they were forced to describe them at all.

Two generations later, slavery was gone and Jim Crow had begun. Suddenly, one provable drop of “black blood” might be all it took to find yourself on the wrong side of the color line. George Spencer had moved across the border to the hill country of western Virginia, where he was doing fine until a feud started with a wealthier family, who started spreading rumors that the Spencers were “God damned negroes”. A slander trial ensued, with detectives going back to Kentucky to interview old people about where Jordan Spencer might have come from and whether he anyone had ever suggested he might not be white. A jury found against the Spencers, but the Virginia Supreme Court threw the verdict out and the case was never retried. That was enough for the locals to go on treating the Spencers as white, maybe with an occasional wink or nod.

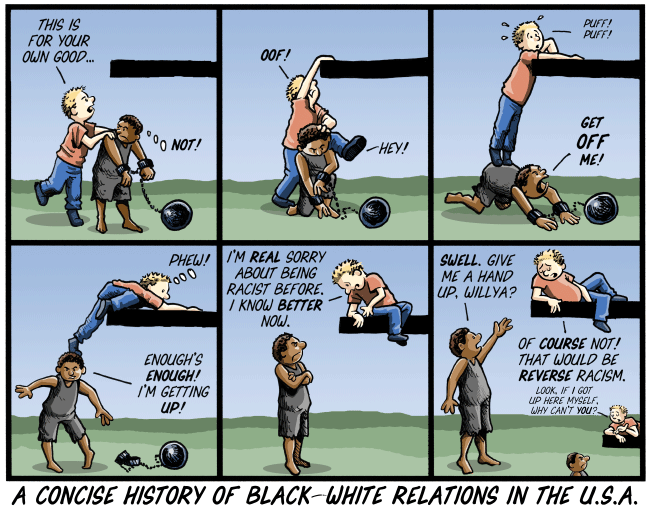

Summing up. We look back on American history and say that people (including our own ancestors) were “white” or “black” as if those words had some natural meaning that remained constant through time and space. But in fact, the lines between the races have fluctuated, and even the apparent rules have applied differently to one family than to another. Sometimes all you had to do to cross the color line was move somewhere new and let people make assumptions about you.

At all times in American history, being considered white has brought certain advantages, and in every generation there have been light-skinned people who didn’t see why they or their children shouldn’t have those advantages. Both sides of the racial divide have had reason to minimize this phenomenon. For whites, the fact that the color line was fluid and permeable undermined the whole concept of white superiority. For blacks, those who forsook their black heritage lent credence to the notion that African ancestry was something to be ashamed of. And those who crossed over had reason to hope no one would ever find out, including, perhaps, their own children.

But reclaiming the “hidden migration” has a role to play in ending racism and healing the racial divide. Not only is racial purity an unworthy goal, it is a myth. We have never had racial purity in America. We are a lot closer to being one big family than most of us ever suspected.

BTW, I thought I’d head off an obvious comment: I realize that this post’s title assumes the reader is white (or thinks s/he is). I ask the indulgence and forgiveness of the Sift’s non-white readers. No inclusive title I could think of brought the issue to a head quite so sharply.

Wednesday, NBA Commissioner Adam Silver announced his response to the recordings in which L. A. Clippers owner Donald Sterling makes racist statements: Sterling is fined $2.5 million and banned for life from interacting with the Clippers or any other NBA team. Silver can’t force Sterling to sell his team, but he says the other NBA owners collectively can, and he’s going to ask them to do so.

Wednesday, NBA Commissioner Adam Silver announced his response to the recordings in which L. A. Clippers owner Donald Sterling makes racist statements: Sterling is fined $2.5 million and banned for life from interacting with the Clippers or any other NBA team. Silver can’t force Sterling to sell his team, but he says the other NBA owners collectively can, and he’s going to ask them to do so.

Something I’m just beginning to appreciate is how influential the Southern anti-Reconstruction movement that birthed the KKK has been in forming the ideas that are still running around on the extreme Right. If you want initiate yourself into this mindset, I recommend reading Thomas Dixon’s 1905 best-seller

Something I’m just beginning to appreciate is how influential the Southern anti-Reconstruction movement that birthed the KKK has been in forming the ideas that are still running around on the extreme Right. If you want initiate yourself into this mindset, I recommend reading Thomas Dixon’s 1905 best-seller

The

The

Teasing out the different stances that might be called “racism” is at least half the value of Ian Haney Lopez’ recent book

Teasing out the different stances that might be called “racism” is at least half the value of Ian Haney Lopez’ recent book