Citizens shouldn’t let the media make us forget about ourselves.

Judging by the amount of media attention they got, these were the most important political stories of the week: Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders agreed to debate, but then Trump backed out, leading Sanders supporters to launch the #ChickenTrump hashtag. A report on Hillary Clinton’s emails came out. A poll indicated that the California primary is closer than previously thought. Trump’s delegate total went over 50%. Elizabeth Warren criticized Trump, so he began calling her “Pocahontas”. Sanders demanded that Barney Frank be removed as the chair of the DNC’s platform committee. Trump told a California audience that the state isn’t in a drought and has “plenty of water“. Trump accused Bill Clinton of being a rapist, and brought up the 1990s conspiracy theory that Vince Foster was murdered. President Obama said that the prospect of a Trump presidency had foreign leaders “rattled“, and Trump replied that “When you rattle someone, that’s good.” Clinton charged that Trump had been rooting for the 2008 housing collapse. Pundits told us that the tone of the campaign was only going to get worse from here; Trump and Clinton have record disapproval ratings for presidential nominees, and so the debate will have to focus on making the other one even more unpopular.

If you are an American who follows political news, you probably heard or read most of these stories, and you may have gotten emotionally involved — excited or worried or angry — about one or more of them. But if at any time you took a step back from the urgent tone of the coverage, you might have wondered what any of it had to do with you, or with the country you live in. The United States has serious issues to think about and serious decisions to make about what kind of country it is or wants to be. This presidential election, and the congressional elections that are also happening this fall, will play an important role in those decisions.

That’s why I think it’s important, both in our own minds and in our interactions with each other, to keep pulling the discussion back to us and our country. The flaws and foibles and gaffes and strategies of the candidates are shiny objects that can be hard to ignore, and Trump in particular is unusually gifted at drawing attention. But the government of the United States is supposed to be “of the People, by the People, and for the People”. It’s supposed to be about us, not about them.

As I’ve often discussed before, the important issues of our country and how it will be governed, of the decisions we have to make and the implications those decisions will have, are not news in the sense that our journalistic culture understands it. Our sense of those concerns evolves slowly, and almost never changes significantly from one day to the next. It seldom crystallizes into events that are breaking and require minute-to-minute updates. At best, a breaking news event like the Ferguson demonstrations or the Baltimore riot will occasionally give journalists a hook on which to hang a discussion of an important issue that isn’t news, like our centuries-long racial divide. (Picture trying to cover it without the hook: “This just in: America’s racial problem has changed since 1865 and 1965, but it’s still there.”)

So let’s back away from the addictive soap opera of the candidates and try to refocus on the questions this election really ought to be about.

Who can be a real American?

In the middle of the 20th century (about the time I was born), if you had asked people anywhere in the world to describe “an American”, you’d have gotten a pretty clear picture: Americans were white and spoke English. They were Christians (with a few Jews mixed in, but they were assimilating and you probably couldn’t tell), and mostly Protestants. They lived in households where two parents — a man and a woman, obviously — were trying (or hoping) to raise at least two children. They either owned a house (that they probably still owed money on) or were saving to buy one. They owned at least one car, and hoped to buy a bigger and better one soon.

If you needed someone to lead or speak for a group of Americans, you picked a man. American women might get an education and work temporarily as teachers or nurses or secretaries, but only until they could find a husband and start raising children.

Of course, everyone knew that other kinds of people lived in America: blacks, obviously; Hispanics and various recent immigrants whose English might be spotty; Native Americans, who were still Indians then; Jews who weren’t assimilating and might make a nuisance about working on Saturday, or even wear a yarmulke in public; single people who weren’t looking to marry or raise children (but might be sexually active anyway); women with real careers; gays and lesbians (but not transgender people or even bisexuals, whose existence wasn’t recognized yet); atheists, Muslims, and followers of non-Biblical religions; the homeless and others who lived in long-term poverty; folks whose physical or mental abilities were outside the “normal” range; and so on.

But they were Americans-with-an-asterisk. Such people weren’t really “us”, but we were magnanimous enough to tolerate them living in our country — for which we expected them to be grateful.

Providing services for the “real” Americans was comparatively easy: You could do everything in English. You didn’t have to concern yourself with handicapped access or learning disabilities. You promoted people who fit your image of a leader, and didn’t worry about whether that was fair. You told whatever jokes real Americans found funny, because anybody those jokes might offend needed to get a sense of humor. The schools taught white male history and celebrated Christian holidays. Every child had two married parents, and you could assume that the mother was at home during the day. Everybody had a definite gender and was straight, so if you kept the boys and girls apart you had dealt with the sex issue.

If those arrangements didn’t work for somebody, that was their problem. If they wanted the system to work better for them, they should learn to be more normal.

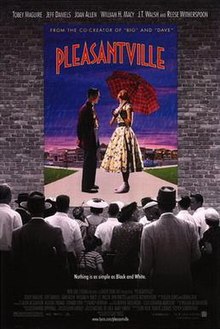

It’s easy to imagine that this mid-20th-century Pleasantville America is ancient history now, but it existed in living memory and still figures as ideal in many people’s minds. Explicitly advocating a return to those days is rare. But that desire isn’t gone, it’s just underground.

It’s easy to imagine that this mid-20th-century Pleasantville America is ancient history now, but it existed in living memory and still figures as ideal in many people’s minds. Explicitly advocating a return to those days is rare. But that desire isn’t gone, it’s just underground.

For years, that underground nostalgia has figured in a wide variety of political issues. But it has been the particular genius of Donald Trump to pull them together and bring them as close to the surface as possible without making an explicit appeal to turn back the clock and re-impose the norms of that era. “Make America great again!” doesn’t exactly promise a return to Pleasantville, but for many people that’s what it evokes.

What, after all, does the complaint about political correctness amount to once you get past “Why can’t I get away with behaving like my grandfather did?”

We can picture rounding up and deporting undocumented Mexicans by the millions, because they’re Mexicans. They were never going to be real Americans anyway. Ditto for Muslims. It would have been absurd to stop letting Italians into the country because of Mafia violence, or to shut off Irish immigration because of IRA terrorism. But Muslims were never going to be real Americans anyway, so why not keep them out? (BTW: As I explained a few weeks ago, the excuse that the Muslim ban is “temporary” is bogus. If nobody can tell you when or how something is going to end, it’s not temporary.)

All the recent complaints about “religious liberty” fall apart once you dispense with the notion that Christian sensibilities deserve more respect than non-Christian ones, or that same-sex couples deserve less respect than opposite-sex couples.

On the other side, Black Lives Matter is asking us to address that underground, often subconscious, feeling that black lives really aren’t on the same level as white lives. If a young black man is dead, it just doesn’t have the same claim on the public imagination — or on the diligence of the justice system — that a white death would. How many black or Latina girls vanish during a news cycle that obsesses over some missing white girl? (For that matter, how many white presidents have seen a large chunk of the country doubt their birth certificates, or have been interrupted during State of the Union addresses by congressmen shouting “You lie!”?)

But bringing myself back to the theme: The issue here isn’t Trump, it’s us. Do we want to think of some Americans as more “real” than others, or do we want to continue the decades-long process of bringing more Americans into the mainstream?

That question won’t be stated explicitly on your ballot this November, like a referendum issue. But it’s one of the most important things we’ll be deciding.

What role should American power play in the world?

I had a pretty clear opinion on that last question, but I find this one much harder to call.

The traditional answer, which goes back to the Truman administration and has existed as a bipartisan consensus in the foreign-policy establishment ever since, is that American power is the bedrock on which to build a system of alliances that maintains order in the world. The archetype here is NATO, which has kept the peace in Europe for 70 years.

That policy involves continuing to spend a lot on our military, and risks getting us involved in wars from time to time. (Within that establishment consensus, though, there is still variation in how willing we should be to go to war. The Iraq War, for example, was a choice of the Bush administration, not a necessary result of the bipartisan consensus.) The post-Truman consensus views America as “the indispensable nation”; without us, the world community lacks both the means and the will to stand up to rogue actors on the world stage.

A big part of our role is in nuclear non-proliferation. We intimidate countries like Iran out of building a bomb, and we extend our nuclear umbrella over Japan so that it doesn’t need one. The fact that no nuclear weapon has been fired in anger since 1945 is a major success of the establishment consensus.

Of our current candidates, Hillary Clinton (who as Secretary of State negotiated the international sanctions that forced Iran into the recent nuclear deal) is the one most in line with the foreign policy status quo. Bernie Sanders is more identified with strengthened international institutions which — if they could be constructed and work — would make American leadership more dispensable. To the extent that he has a clear position at all, Donald Trump is more inclined to pull back and let other countries fend for themselves. He has, for example, said that NATO is “obsolete” and suggested that we might be better off if Japan had its own nuclear weapons and could defend itself against North Korea’s nukes. On the other hand, he has also recently suggested that we bomb Libya, so it’s hard to get a clear handle on whether he’s more or less hawkish than Clinton.

Should we be doing anything about climate change?

Among scientists, there really are two sides to the climate-change debate: One side believes that the greenhouse gases we are pumping into the atmosphere threaten to change the Earth’s climate in ways that will cause serious distress to millions or even billions of people, and the other side is funded by the fossil fuel industry.

It’s really that simple. There are honest scientific disagreements about the pace of climate change and its exact mechanisms, but the basic picture is clear to any scientist who comes to the question without a vested interest: Burning fossil fuels is raising the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. An increase in greenhouse gases causes the Earth to radiate less heat into space. So you would expect to see a long-term warming trend since the Industrial Revolution got rolling, and in fact that’s what the data shows — despite the continued existence of snowballs, which has been demonstrated by a senator funded by the fossil fuel industry.

Unfortunately, burning fossil fuels is both convenient and fun, at least in the short term. And if you don’t put any price on the long-term damage you’re doing, it’s also economical. In reality, doing nothing about climate change is like going without health insurance or refusing to do any maintenance on your house or car. Those decisions can improve your short-term budget picture, which now might have room for that Hawaiian vacation your original calculation said you couldn’t afford. Your mom might insist that you should account for your risk of getting sick or needing some major repair, but she’s always been a spoilsport.

Unfortunately, burning fossil fuels is both convenient and fun, at least in the short term. And if you don’t put any price on the long-term damage you’re doing, it’s also economical. In reality, doing nothing about climate change is like going without health insurance or refusing to do any maintenance on your house or car. Those decisions can improve your short-term budget picture, which now might have room for that Hawaiian vacation your original calculation said you couldn’t afford. Your mom might insist that you should account for your risk of getting sick or needing some major repair, but she’s always been a spoilsport.

That’s the debate that’s going on now. If you figure in the real economic costs of letting the Earth get hotter and hotter — dealing with tens of millions of refugees from regions that will soon be underwater, building a seawall around Florida, moving our breadbasket from Iowa to wherever the temperate zone is going to be in 50 years, rebuilding after the stronger and more frequent hurricanes that are coming, and so on, then burning fossil fuels is really, really expensive. But if you decide to let future generations worry about those costs and just get on with enjoying life now, then coal and oil are still cheap compared to most renewable energy sources.

So what should we do?

Unfortunately, nobody has come up with a good way to re-insert the costs of climate change into the market without involving government, or to do any effective mitigation without international agreements among governments, of which the recent Paris Agreement is just a baby step in the right direction. And to one of our political parties, government is a four-letter word and world government is an apocalyptic horror. So the split inside the Republican Party is between those who pretend climate change isn’t happening, and those who think nothing can or should be done about it. (Trump is on the pretend-it-isn’t-happening side.)

President Obama has been taking some action to limit greenhouse gas emissions, but without cooperation from Congress his powers are pretty limited. (It’s worth noting how close we came to passing a cap-and-trade bill to put a price on carbon before the Republicans took over Congress in 2010. What little Obama’s managed to do since may still get undone by the Supreme Court, particularly if its conservative majority is restored.)

Both Clinton and Sanders take climate change seriously. As is true across the board, Sanders’ proposals are simpler and more sweeping (like “ban fracking”) while Clinton’s are wonkier and more complicated. (In a debate, she listed the problems with fracking — methane leaks, groundwater pollution, earthquakes — and proposed controlling them through regulation. She concluded: “By the time we get through all of my conditions, I do not think there will be many places in America where fracking will continue to take place.”) But like Obama, neither of them will accomplish much if we can’t flip Congress.

Trump, meanwhile, is doing his best impersonation of an environmentalist’s worst nightmare. He thinks climate change is a hoax, wants to reverse President Obama’s executive orders to limit carbon pollution, has pledged to undo the Paris Agreement, and to get back to burning more coal.

How should we defend ourselves from terrorism?

There are two points of view on ISIS and Al Qaeda-style terrorism, and they roughly correspond to the split between the two parties.

From President Obama’s point of view, the most important thing about battle with terrorism is to keep it contained. Right now, a relatively small percentage of the world’s Muslims support ISIS or Al Qaeda, while the vast majority are hoping to find a place for themselves inside the world order as it exists. (That includes 3.3 million American Muslims. If any more than a handful of them supported terrorism, we’d be in serious trouble.) We want to keep tightening the noose on ISIS in Iraq and Syria, and keep closing in on terrorist groups elsewhere in the world, while remaining on good terms with the rest of the Muslim community.

From this point of view — which I’ve described in more detail here and illustrated with an analogy here — the worst thing that could happen would be for these terrorist incidents to touch off a world war between Islam and Christendom.

The opposite view, represented not just by Trump but by several of the Republican rivals he defeated, is that we are already in such a war, so we should go all out and win it: Carpet bomb any territory ISIS holds, without regard to civilian casualties. Discriminate openly against Muslims at home and ban any new Muslims from coming here.

Like Obama, I believe that the main result of these policies would be to convince Muslims that there is no place for them in a world order dominated by the United States. Rather than a few dozen pro-ISIS American terrorists, we might have tens of thousands. If we plan to go that way, we might as well start rounding up 3.3 million Americans right now.

Clinton and Sanders are both roughly on the same page with Obama. Despite being Jewish and having lived on a kibbutz, Sanders is less identified with the current Israeli government than either Obama or Clinton, to the extent that makes a difference.

Can we give all Americans a decent shot at success? How?

Pre-Trump, Republicans almost without exception argued that all we need to do to produce explosive growth and create near-limitless economic opportunity for everybody is to get government out of the way: Lower taxes, cut regulations, cut government programs, negotiate free trade with other countries, and let the free market work its magic. (Jeb Bush, for example, argued that his small-government policies as governor of Florida — and not the housing bubble that popped shortly after he left office — had led to 4% annual economic growth, so similar policies would do the same thing for the whole country.)

Trump has called this prescription into question.

If you think about it, the economy is rigged, the banking system is rigged, there’s a lot of things that are rigged in this world of ours, and that’s why a lot of you haven’t had an effective wage increase in 20 years.

However, he has not yet replaced it with any coherent economic view or set of policies. His tax plan, for example, is the same sort of let-the-rich-keep-their-money proposal any other Republican might make. He promises to renegotiate our international trade agreements in ways that will bring back all the manufacturing jobs that left the country over the last few decades, but nobody’s been able to explain exactly how that would work.

At least, though, Trump is recognizing the long-term stagnation of America’s middle class. Other Republicans liked to pretend that was all Obama’s fault, as if the 2008 collapse hadn’t happened under Bush, and — more importantly — as if the overall wage stagnation didn’t date back to Reagan.

One branch of liberal economics, the one that is best exemplified by Bernie Sanders, argues that the problem is the over-concentration of wealth at the very top. This can devolve into a the-rich-have-your-money argument, but the essence of it is more subtle than that: Over-concentration of wealth has created a global demand problem. When middle-class and poor people have more money, they spend it on things whose production can be increased, like cars or iPhones or Big Macs. That increased production creates jobs and puts more money in the pockets of poor and middle-class people, resulting in a virtuous demand/production/demand cycle that is more-or-less the definition of economic growth.

By contrast, when very rich people have more money, they are more likely to spend it on unique items, like van Gogh paintings or Mediterranean islands. The production of such things can’t be increased, so what we see instead are asset bubbles, where production flattens and the prices of rare goods get bid higher and higher.

For the last few decades, we’ve been living in an asset-bubble world rather than an economic-growth world. The liberal solution is to tax that excess money away from the rich, and spend it on things that benefit poor and middle-class people, like health care and infrastructure.

However, there is a long-term problem that neither liberal nor conservative economics has a clear answer for: As artificial intelligence creeps into our technology, we get closer to a different kind of technological unemployment than we have seen before, in which people of limited skills may have nothing they can offer the economy. (In A Farewell to Alms Gregory Clark makes a scary analogy: In 1901, the British economy provided employment for 3 million horses, but almost all those jobs have gone away. Why couldn’t that happen to people?)

As we approach that AI-driven world, the connection between production and consumption — which has driven the world economy for as long as there has been a world economy — will have to be rethought. I don’t see anybody in either party doing that.

So what major themes have I left out? Put them in the comments.