2016 brought white nationalism into the mainstream discussion. Now we have to answer questions we used to ignore.

Writing them off. Throughout my lifetime, liberals have felt that we didn’t really need to argue against the more explicit forms of white racism. The KKK was bad; Jim Crow was bad; the Nazis were bad — that was pretty much all you needed to know.

Of course you’d run into arguments where racism might play a more subtle role and be harder to isolate: Affirmative action is unfair to whites; neighborhood schools are more important than desegregation; the over-representation of blacks in prisons or among the poor is due to their own broken family structure and lack of middle-class values; and so on. Whites who weren’t necessarily hostile to blacks or to civil rights in the abstract often found these points convincing, and some skill was required to defend the liberal view without alienating people who might be with you on some other issue.

But if the conversation came around to “I just think they’re genetically inferior” or “I’d like to send them all back to Africa” or “The Jews run everything anyway”, you didn’t need any skill. Just stop the conversation and write those people off. That kind of dinosaur racism was dying a well-deserved death, and those who still spouted it were probably turning off a lot more people than they convinced.

Many forms of white grievance just merited a one-line answer. Why isn’t there a White History Month? Because in American schools every month is White History Month; teachers don’t need any special reminder to mention George Washington or Thomas Edison.

You particularly didn’t need to argue against explicit racism during political campaigns, because all major national candidates considered racism toxic. That’s why there were “dog whistles“: Even a candidate as conservative as Ronald Reagan couldn’t appear to side with white racists, so he went to a town made famous by civil-rights murders and came out in favor of “states rights”. That was as far as he could go without risking a backlash from whites who found racism disgusting.

The new world of 2016. But the 2016 campaign sent us a clear message that times are changing. It was never any secret who white racists were supporting for president, and Donald Trump did relatively little to distance himself from them. When David Duke, an unrepentant former KKK grand wizard, endorsed him, Trump’s first reaction was to refuse to reject that endorsement:

I know nothing about David Duke. I know nothing about white supremacists. And so you’re asking me a question that I’m supposed to be talking about people that I know nothing about.

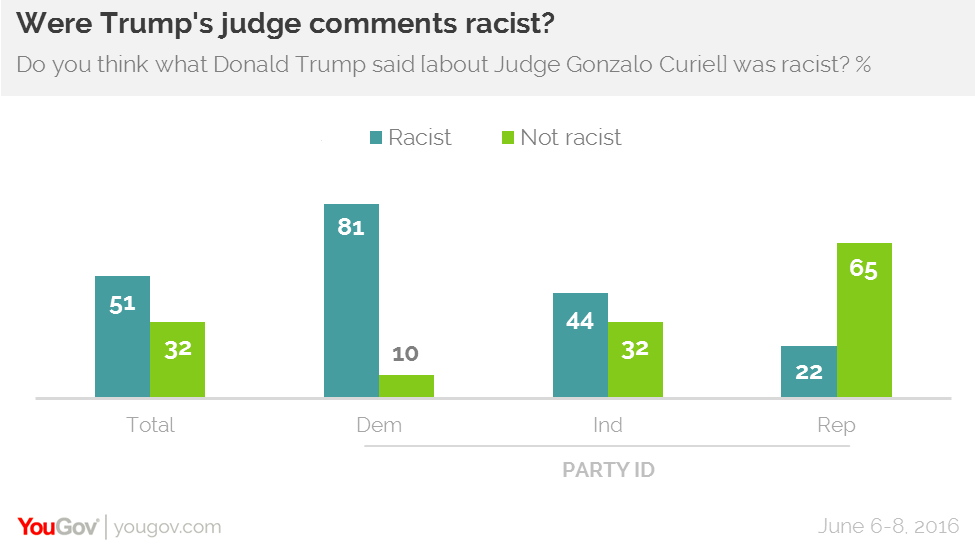

His speech to the Republican Convention centered on a non-existent immigrant crime wave: brown Hispanics and Muslims are coming for your family. Indiana-born Judge Curiel couldn’t possibly handle the Trump University fraud case fairly, because “He’s a Mexican.” He called for an explicit religious test on immigrants and tourists. He retweeted stuff from @WhiteGenocideTM. Trump’s ostensible appeals to black voters were typically delivered in white suburbs to almost entirely white audiences, and consisted of negative stereotypes of black life:

You’re living in poverty, your schools are no good, you have no jobs, 58 percent of your youth is unemployed. What the hell do you have to lose?

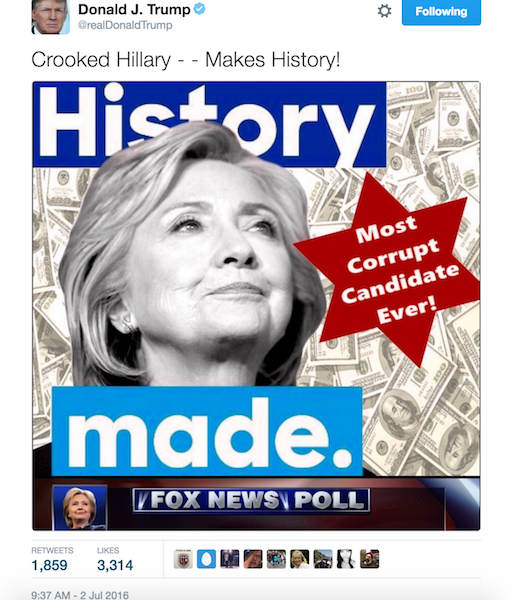

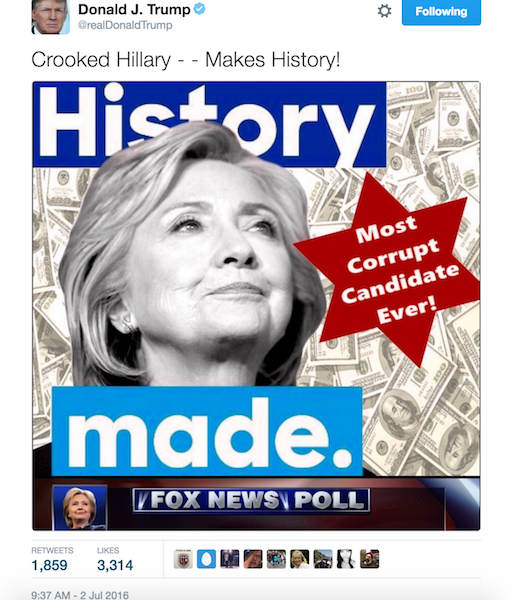

He even touched what (since the Holocaust) has been the third rail of American political racism: antisemitism. In what Senator Al Franken called a “German shepherd whistle“, Trump’s closing-argument commercial connected Clinton to Jewish financiers, echoing an earlier tweeted image of Clinton, a pile of money, and a Star of David — which also originated with white supremacists. (Trump has never explained how so many racist memes come to his attention. Does he follow Twitter users like @WhiteGenocideTM?)

He even touched what (since the Holocaust) has been the third rail of American political racism: antisemitism. In what Senator Al Franken called a “German shepherd whistle“, Trump’s closing-argument commercial connected Clinton to Jewish financiers, echoing an earlier tweeted image of Clinton, a pile of money, and a Star of David — which also originated with white supremacists. (Trump has never explained how so many racist memes come to his attention. Does he follow Twitter users like @WhiteGenocideTM?)

Since the election, Trump has gotten far more agitated by a polite appeal from the cast of Hamilton to “uphold our American values and to work on behalf of all of us” than by a roomful of white supremacists shouting “Hail Trump!” and giving straight-arm Nazi salutes. When asked about the neo-Nazis during his interview at The New York Times, he said, “Boy, you are really into this stuff, huh?” When pressed, he said “I disavow and condemn.” But it wasn’t at all something he felt he needed to clear up.

So Trump doesn’t treat racism as toxic, and in fact it hasn’t been. He won anyway, or perhaps he won because. And that puts us in a new world. White nationalist and white grievance arguments are entering the mainstream, and we have to answer them now.

White grievance. The essence of the white-grievance argument is that mainstream culture imposes a double standard on whites, and puts us in impossible situations where anything we might say or do is wrong.

At that neo-Nazi conference Trump eventually got around to disavowing, the speaker who started the “Hail Trump!” chorus was Richard Spencer. He put the white-grievance argument this way:

In the Current Year, a white who takes pride in his ancestors’ accomplishments is evil, but a white who refuses to accept guilt for his ancestors’ sins is also evil.

In the Current Year, white families work their whole lives to send their children to universities where they will be told how despicable they are.

In the Current Year, the powerful lecture the powerless about how they don’t recognize their own “privilege.”

In the Current Year, a wealthy Jewish celebrity bragging about the “end of white men” is “speaking truth to power.’

In the Current Year, if you are physically strong, you are fragile. Black is beautiful, but whiteness is toxic.

In a lot of ways, I’m Spencer’s target audience: I’m a white man whose German Lutheran ancestors settled in rural Illinois just before the Civil War. I think I come from good people — nobody who shows up in history books, but ordinary folks who worked hard and did right by their neighbors and raised their kids to do the same. My parents’ hard work (and mine; I got scholarships) sent me to universities (Michigan State and the University of Chicago), where I did indeed get introduced to the dark side of American racial history and some of the advantages being white had given me.

Like Spencer, I don’t believe that whites are despicable or that whiteness is toxic. I do think slavery was a very bad thing — not sure whether Spencer agrees or not — but my personal feelings about its legacy are too complicated to sum up as guilt. (BTW: I think right-wingers went off the deep end responding to Lena Dunham’s short conversation with her Dad about “the extinction of white men”, and I’m not sure why her Jewishness is relevant. I don’t feel the least bit threatened by her animated video, and I’m confident that no actual white men were harmed in the drawing of it.)

So why don’t I have the kind of white pride Spencer is trying to promote and defend? And why don’t I feel aggrieved by a culture that doesn’t approve of expressing that pride?

My pride. I’ve got some. As I said already, I feel pride in my ancestors.

I also feel pride in being an American. I write a lot on this blog about American history and the Constitution and the tradition of our laws, and I hope my words convey the amazement and wonder I find in it all. Naturally, we have villains as well as heroes, and I try not to pretend otherwise, but none of that ruins it for me. In some ways it’s even better once you understand that none of the characters in our story were gods, that they were humans with all the flaws you can see in humans today. Many of the great things they did were also terrible at the same time, and at the end of it all, somehow, here we are.

I love the English language, and what other writers have done with it. Not just the giants like Shakespeare or Faulkner, but anybody who can turn a good phrase. If you ever happen to be in the room while I have my nose in a book, don’t be surprised if I suddenly jump up and interrupt everybody else’s conversation with: “Oh, you have to hear this!” and then start reading aloud.

I take pride in Western Culture, the whole dead-white-male tradition of the so-called “Great Books”. I have loved Plato since I stumbled across a translation of “Apology of Socrates” in junior high. The abstract beauty of Euclid, Periclean democracy, the cosmopolitan Stoics, infinitely logical Spinoza, and that long, long dialog (continuing to this very moment) between what we want to believe about the world and what we can make sense out of — irrationally, I feel like it is all in some way my own, as if in rediscovering it I had thought of it myself.

I even feel a certain amount of ethnic German pride, though American Germans have been playing that down since the world wars. I can’t speak the language, but I read it well enough to appreciate its unpretentious logic, where you can reason a word out syllable-by-syllable in the same way you might sound it out it letter-by-letter. (Wahrscheinlichkeit, for example, breaks down as true-seeming-ness: probability.) Watching the World Cup, I started rooting for the German team as soon as the Americans were eliminated.

If you ask white supremacists about their “white pride”, they’ll point to a lot of this same stuff: White people wrote the Constitution, created German and English, and are responsible for nearly all the Western classics. The pride I just expressed, they would claim, is white pride.

And that’s where they lose me.

My identity. Ancestry is largely genetic, I’ll grant you. But the other pieces of my identity aren’t. When I listen to the Hamilton soundtrack, for example, I feel both American pride and English-language pride; the fact that Lin-Manuel Miranda is Puerto Rican and most of the cast is something other than white doesn’t diminish that.

One of the things I love about my national heritage is its lack of boundaries. If you have something good in you and you want to bring it to America, we’ll take it and make it our own. Is Einstein too Jewish for Hitler? Fine, we’ll take him. English literature is the same way: Joseph Conrad‘s first language was Polish, but who cares? Heart of Darkness is an English classic. Western culture is great because it is porous and permeable; anybody who masters it, like Salman Rushdie, becomes part of it, no matter where they were born or who their parents were.

Without that permeability, I couldn’t claim most of Western culture either. Plato and Homer were Greek; they’re no relation of mine. (If Plato ever talked about my Germanic ancestors, he would have used the Greek word barbaros, from which we derive barbarian.) Descartes was French, Tolstoy Russian. So why should it bother me that Edward Said was Arab or Haruki Murakami is Japanese? I envy the things Martin Luther King did with spoken English and Ta-Nehisi Coates does with written English. Should I not learn from them because they’re black?

Anybody who claims Western culture as “white” doesn’t really get the point of Western culture.

White identity is artificial. But there’s an even bigger problem with identifying as white, which the last section only hinted at: Most of the historical heroes I would want to claim had no idea they were white.

The Pilgrims who landed at Plymouth Rock didn’t think they were white, they thought they were English. Columbus wasn’t white, or even Italian; he was a Genoan working for Spain. (Spain itself was a new idea then, having just formed from the union of Castille and Aragon.) Shakespeare, Milton, and Cervantes weren’t white. Whiteness just wasn’t a thing yet.

When it did it become a thing? When the white/black distinction became the basis of slavery.

Blackness was invented at the same moment. The dark-skinned people who were loaded onto the slavers’ ships weren’t black, they were Yoruba, Ashanti, Dogon and dozens or maybe hundreds of other ethnicities. They spoke different languages, ate different foods, and worshiped different gods. They became black when their new masters imposed a common experience on them and saw them as interchangeable.

Blackness was invented at the same moment. The dark-skinned people who were loaded onto the slavers’ ships weren’t black, they were Yoruba, Ashanti, Dogon and dozens or maybe hundreds of other ethnicities. They spoke different languages, ate different foods, and worshiped different gods. They became black when their new masters imposed a common experience on them and saw them as interchangeable.

Something similar, if much less extreme, happened to the Poles, Czechs, Irish, and other Europeans who came through Ellis Island. They were allowed to keep a little of their previous identity, but considered backwards if they took it too seriously. (You can see that process happening in the background of all those making-of-the-Mafia movies. Lucky Luciano had become an Italian-American, but the previous generation of bosses — Maranzano, Masseria — were still greaseballs.)

Imagine trying to organize a White Heritage Festival. What food would you serve? What ancestral costumes would you dress your staff in? The reason those questions seem so silly is that there is no white culture. There never has been.

Whiteness is about being the master rather than the slave. That’s the sum total of it.

Why white pride is different from black pride. Whiteness and blackness were created at the same moment, by the same act of enslavement. But they were not created equal. White identity and black identity are both in some sense artificial, but there is no equivalency between them.

When Africans were enslaved, the masters did their best to erase any prior African identity. Italian immigrants could form their own neighborhoods, like Little Italy in Manhattan. On the frontier, entire regions were settled by Germans or Swedes. But the cotton plantations did not recognize any prior tribal distinctions, and any attempt by the slaves to practice a non-Christian religion or preserve a language the masters did not understand was put down harshly.

Slaves of all tribes were all housed together, and encouraged to breed like cattle. To the extent they were taught anything about their African motherland, they were told it was a land of savages who were little better than animals. How generous the white man had been, to bring them to a Christian land and teach them civilization!

When you grasp even that much about the black experience in America, you understand the job black pride needed (and still needs) to do: On the one hand, it needed to celebrate the polyglot culture the slaves made for themselves, how it continued after Emancipation, and its contributions to the larger American culture. And on the other, it needed to reach back beyond slavery, and recapture a sense of Africa as a place of origin, with its own history and traditions.

There is no similar task for white pride. I know exactly what part of Europe my ancestors came from, and German ethnicity is there for me whenever I want it. If I eat schnitzel and drink beer during Oktoberfest, no one will condemn me. I could put on lederhosen and dance to an oompah band if that would do something for me. If I want to go deeper, I could read Faust, recite the poetry of Rilke, or attend a Wagner opera.

There is no similar task for white pride. I know exactly what part of Europe my ancestors came from, and German ethnicity is there for me whenever I want it. If I eat schnitzel and drink beer during Oktoberfest, no one will condemn me. I could put on lederhosen and dance to an oompah band if that would do something for me. If I want to go deeper, I could read Faust, recite the poetry of Rilke, or attend a Wagner opera.

Similarly, you can celebrate your Irish roots on St. Patrick’s Day, and make something more out of that identity if you need to. If Italians want to congregate on Columbus Day, critics might dispute their choice of hero, but not their right to a holiday. A few miles from my apartment, there’s a Greek festival every year on the day of some saint whose name I can never remember. It’s a good place to get baklava and spanakopita.

The various European identities were never completely erased, and are totally recoverable. In most cases, you can visit the original country, where the original culture may have evolved since your ancestors left, but was never overwritten by colonialism. There is no hole for white pride to fill.

Dark whiteness. But there is a dark place white pride can go to, and in practice it quickly goes there. Whiteness and blackness originate in slavery. So in the same way that black pride focuses on healing the injuries of slavery, white pride can celebrate that enslavement.

Dark whiteness. But there is a dark place white pride can go to, and in practice it quickly goes there. Whiteness and blackness originate in slavery. So in the same way that black pride focuses on healing the injuries of slavery, white pride can celebrate that enslavement.

Maybe there is no white culture, but there was Confederate culture, the lifestyle of the slave-master. Spend any length of time on a white-pride web site, and you’ll run into the stars-and-bars, and “heroes” like Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, and Nathan Bedford Forrest. You’ll run into white people whitesplaining that slavery wasn’t really so bad, that the house slaves were practically members of the family, that blacks were better off on the plantations of Charleston than they are in the ghettos of Detroit, and so on.

Strangely, I never hear any black people, no matter how poor they are, waxing nostalgic about the old plantation days — just white people claiming that they should.

Guilt and responsibility. Probably the most persuasive part of the white-grievance argument is that people are trying to make us feel guilty for things we haven’t done. I personally had nothing to do with enslaving the blacks, committing genocide against the Jews of Europe, or stealing the homelands of the Native American tribes. All of that happened long before I was born. So why do liberals want me to feel guilty about it?

a white who takes pride in his ancestors’ accomplishments is evil, but a white who refuses to accept guilt for his ancestors’ sins is also evil.

This objection is based on a gross (and I think intentional) misreading of the liberal position on race.

Guilt is personal, not collective; if you didn’t do it, you shouldn’t feel guilty about it. But responsibility for making the world more just is collective.

Blacks were brought to America by force. They had their ethnic identities stripped away by force. Their labor built a great deal of this country and its wealth, both during slavery and during the times that followed when they were an exploited underclass. In exchange, they received very little of that wealth. Today, many continue to live as an underclass, with slim opportunities to make a better life.

I didn’t do that to them. No living white individual did. But American society as a whole — all of it, not just the white part — bears a responsibility to correct that injustice, or at least to stop perpetuating it.

How to do that, what would be fair, and what stands a chance of working — those are all open questions. Many legitimate points of view are possible. What is not legitimate, and what individual whites ought to feel guilty about, is taking a sucks-to-be-them attitude and sloughing off responsibility entirely. That’s not just something our collective ancestors did long ago. That is something we might be doing as individuals right now.

So what are we being asked to do? Not to feel guilty, but to open our eyes and stop rationalizing that American society is already just and everybody is exactly where they deserve to be. To recognize the ways that the game has been rigged in our favor. And to participate — fully, intelligently, responsibly — in figuring out and implementing plans to achieve a more just society.

Personally, I find that a project that I — as an American, a German-American, a participant in Western culture, and yes, even as a white — can take pride in.

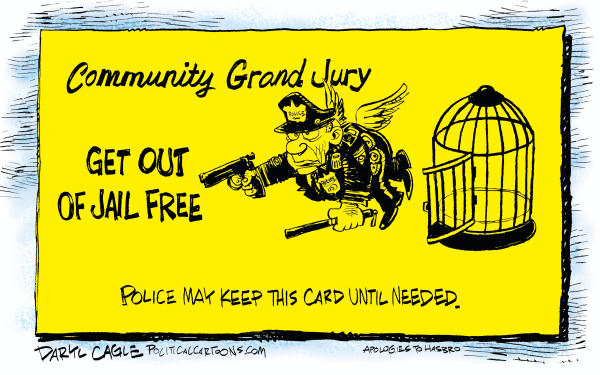

Recalling Ferguson. I remember exactly when I came to accept that Darren Wilson should not be prosecuted for killing Michael Brown: when I read

Recalling Ferguson. I remember exactly when I came to accept that Darren Wilson should not be prosecuted for killing Michael Brown: when I read

There is no similar task for white pride. I know exactly what part of Europe my ancestors came from, and German ethnicity is there for me whenever I want it. If I eat schnitzel and drink beer during Oktoberfest, no one will condemn me. I could put on lederhosen and dance to an oompah band if that would do something for me. If I want to go deeper, I could read Faust, recite the poetry of Rilke, or attend a Wagner opera.

There is no similar task for white pride. I know exactly what part of Europe my ancestors came from, and German ethnicity is there for me whenever I want it. If I eat schnitzel and drink beer during Oktoberfest, no one will condemn me. I could put on lederhosen and dance to an oompah band if that would do something for me. If I want to go deeper, I could read Faust, recite the poetry of Rilke, or attend a Wagner opera. Dark whiteness. But there is a dark place white pride can go to, and in practice it quickly goes there. Whiteness and blackness originate in slavery. So in the same way that black pride focuses on healing the injuries of slavery, white pride can celebrate that enslavement.

Dark whiteness. But there is a dark place white pride can go to, and in practice it quickly goes there. Whiteness and blackness originate in slavery. So in the same way that black pride focuses on healing the injuries of slavery, white pride can celebrate that enslavement.