Biden’s State of the Union wasn’t pretty.

But it probably accomplished more than any SOTU in my lifetime.

This year’s State of the Union was a lesson in the difference between strategy and tactics. President Obama’s SOTUs, like all his speeches, were tactically outstanding. Watching him deliver them was like watching a gifted athlete in his prime. His voice perfectly pitched, his phrases perfectly timed, Obama raised emotion, evoked idealism, and occasionally managed to communicate an idea that was supposed to be too nuanced for this medium. If you had supported him, or even just identified with him as your president after he was elected, you felt pride: This is the man who leads my country.

Joe Biden will never be able to do that. Having struggled his whole life to overcome a childhood stutter, he will always look on a major speech as something to get through rather than an opportunity to shine. After more than half a century in politics, he still sometimes stumbles over his written text, puts emphasis on the wrong words, and races through sentences he ought to drive home.

But that cloud’s silver lining is an aura of authenticity: Biden must be telling it like it is, because he doesn’t have the artistry to lead us astray. Trump is glib and audacious enough to pitch any kind of snake oil, but Biden would never be able to get those words out. It’s already hard enough for him to tell you something he thinks is true.

Tuesday’s speech was vintage Biden. It was too long. His voice was not engaging. And I could easily picture his speechwriter grimacing as the President ruined well-crafted lines that must have looked so good on the computer screen.

And yet, Biden knew his audience, knew his opponents in the room, and delivered a speech that was strategically brilliant. He occupied a strong defensive position and invited his opponents to attack him there, knowing that they would be unable to resist. As Sun Tzu put it:

If your opponent is of choleric temper, seek to irritate him. Pretend to be weak, that he may grow arrogant.

The sound base of Biden’s speech is that he had a good story to tell: record low unemployment, lower drug prices, bipartisan support to rebuild America in ways Trump had promised but never delivered, bringing manufacturing jobs back, the first new gun regulations in decades, NATO reunited against Russian aggression, bipartisan support for research that helps our technology companies compete with China, and a minimum tax to prevent trillion-dollar corporations from paying nothing. He even had good news to tell about the negative parts of the picture: Inflation, the deficit, and Covid are all trending in the right direction.

But rather than unleash a Trump-style brag about his “yuge” accomplishments, Biden was more than willing to share the credit with Republicans.

Folks, as you all know, we used to be number one in the world in infrastructure. We’ve sunk to 13th in the world. The United States of America — 13th in the world in infrastructure, modern infrastructure.

But now we’re coming back because we came together and passed the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law — the largest investment in infrastructure since President Eisenhower’s Interstate Highway System. …

And I mean this sincerely: I want to thank my Republican friends who voted for the law. And my Republican friends who voted against it as well — but I’m still — I still get asked to fund the projects in those districts as well, but don’t worry. I promised I’d be a President for all Americans. We’ll fund these projects. And I’ll see you at the groundbreaking.

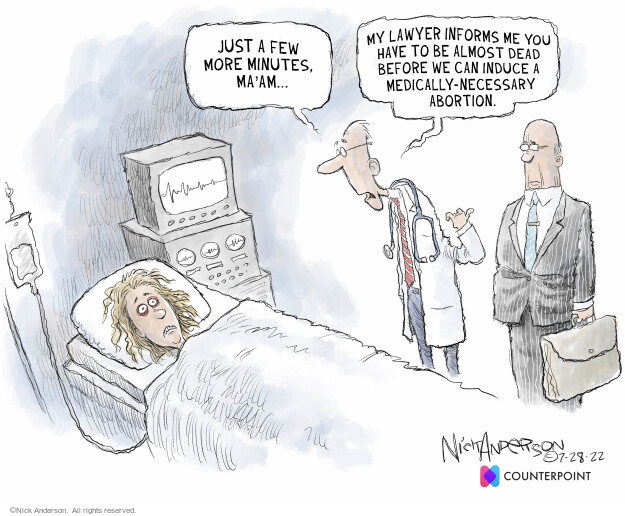

He then looked forward, with plans to address everyday problems large numbers of Americans face: protect Social Security and Medicare, end junk fees and surprise medical bills, restore the child tax credit, help seniors stay in their homes, reduce student debt, and move forward in ways that unite us rather than divide us. Here’s how he presented the often-divisive issue of police reform:

We all want the same thing: neighborhoods free of violence, law enforcement who earns the community’s trust. Just as every cop, when they pin on that badge in the morning, has a right to be able to go home at night, so does everybody else out there. Our children have a right to come home safely.

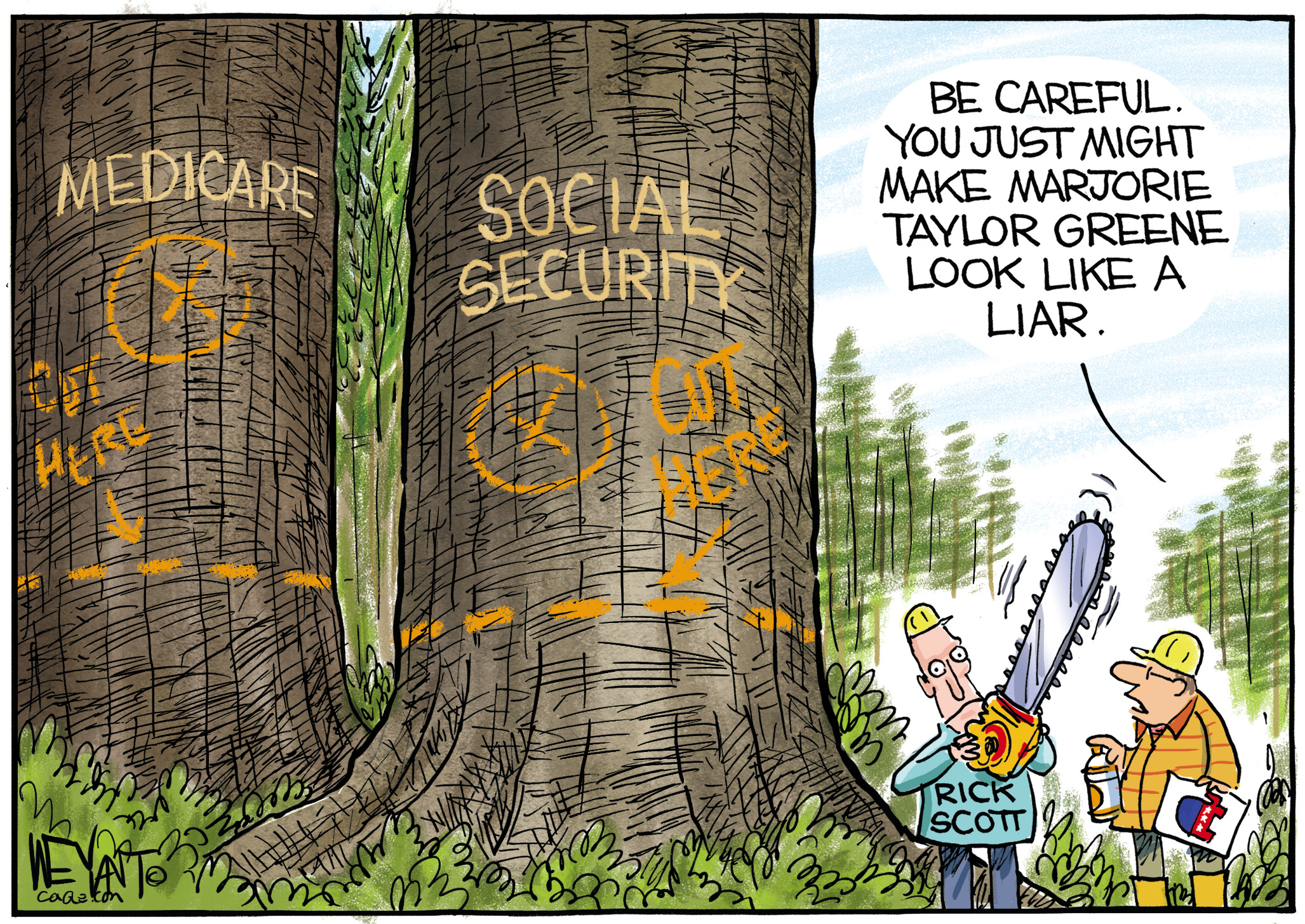

But getting back to Sun Tzu: It’s one thing to occupy a position you can easily defend. The real trick, though, is to get your opponent to attack you there. Biden managed that by pointing to a true fact most Republicans would like American people to ignore: Rick Scott’s proposal to sunset all government programs every five years, which he presented in a glossy brochure last year when he was chair of the National Republican Senatorial Committee. Biden pointed out an obvious consequence of Scott’s plan:

Instead of making the wealthy pay their fair share, some Republicans — some Republicans want Medicare and Social Security to sunset.

That set off a storm of protest from the Republican side, which Biden accepted at face value and made sure the American people took note of: In spite of what they’ve said many times in the past, Republicans don’t want to cut Social Security and Medicare.

Folks — so, folks, as we all apparently agree, Social Security and Medicare is off the — off the books now, right? They’re not to be touched?

All right. All right. We got unanimity! Social Security and Medicare are a lifeline for millions of seniors. Americans have to pay into them from the very first paycheck they’ve started.

So, tonight, let’s all agree — and we apparently are — let’s stand up for seniors. Stand up and show them we will not cut Social Security. We will not cut Medicare.

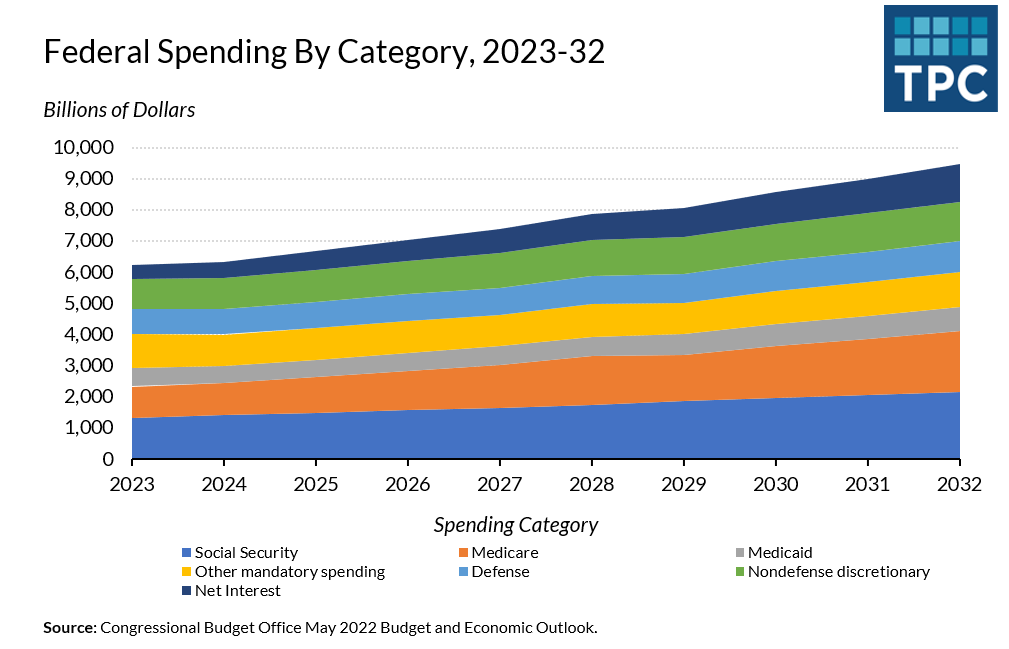

Popular as that position might be, though, it’s still impossible to square with a goal most Republicans are unwilling to give up on: They can’t achieve a balanced budget without tax increases if entitlement programs are off the table. [1]

But no matter how they protested on national TV Tuesday night, apparently some of them still do want to make cuts. Here’s Senator Mike Round (R-SD) on CNN yesterday. (I’m quoting at length to be as fair to him as possible.)

I kind of look at Social Security the way I would at the Department of Defense and our defense spending. We’re never going to not fund defense. But at the same time, every single year we look at how we can make it better. And think it’s about time that we start talking about Social Security and making it better. We’ve got 11 years before we actually see cuts start to happen to people that are on Social Security. It can be very responsible for us to do everything we can to make those funding programs now and the plans right now so that we don’t run out of money in Social Security, and that it continues to provide all the benefits that it does today. Simply looking away from it and pretending like there’s no problem with Social Security is not an appropriate or responsible thing to do. So I guess my preference would be: Let’s start managing it.

That is the line I expect to hear more often as the budget/debt-ceiling battle heats up: It’s completely impossible to make even the richest Americans pay more tax (as Biden proposes), so the trust funds will have to run out of money. [See note 1 again.] When that happens, benefit cuts are coming whether anyone wants them or not. Let’s accept, then, that cuts are inevitable and make it better by managing those cuts — so that billionaires can go on paying lower tax rates than truck drivers and nurses. (They won’t say that last part out loud.)

So that’s the significant policy achievement of Biden’s speech: He got Republicans to paint themselves into a corner on an issue the voters care about.

But there was also a significant political achievement: Biden stage-managed a bit of theater that framed his administration and his Republican opposition in the terms he wants.

Throughout the speech, Biden himself was calm and even generous. He thanked Republicans for their contribution to the bipartisan bills passed these last two years. [2] And he invited further cooperation

To my Republican friends, if we could work together in the last Congress, there’s no reason we can’t work together and find consensus on important things in this Congress as well.

I think — folks, you all are just as informed as I am, but I think the people sent us a clear message: Fighting for the sake of fighting, power for the sake of power, conflict for the sake of conflict gets us nowhere.

That’s always been my vision of our country, and I know it’s many of yours: to restore the soul of this nation; to rebuild the backbone of America, America’s middle class; and to unite the country.

When Republicans responded to parts of his speech with catcalls and angry yells of “Liar!”, Biden took it in stride: They were enraged, he was not. And if they no longer held the views he had just (correctly, and with documentation) attributed to some of them, then he was happy to accept their agreement: “I enjoy conversion,” he said. [3]

The theatrical aspect of the SOTU made something clear to the American people: If there’s a problem with incivility and extremism in Washington, it’s a one-sided problem. Marjorie Taylor Greene and the rest of the shouters made a mockery of the Republican SOTU response, in which new Arkansas governor and former Trump press secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders said:

The choice is between normal or crazy.

Anybody who had been watching what happened in the House chamber had no doubt that this is true. But Sanders has clearly chosen Team Crazy, not Team Normal. And while Biden hoped for unity with “my Republican friends”, Sanders fanned division and doubled down on Trump-style trolling.

President Biden and I don’t have a lot in common. I’m for freedom. He’s for government control. At 40, I’m the youngest governor in the country. At 80, he’s the oldest president in American history. I’m the first woman to lead my state. He’s the first man to surrender his presidency to a woke mob that can’t even tell you what a woman is.

And she painted conservatives as the innocent victims of that “woke mob”.

We are under attack in a left-wing culture war we didn’t start and never wanted to fight. Every day, we are told that we must partake in their rituals, salute their flags, and worship their false idols…all while big government colludes with Big Tech to strip away the most American thing there is—your freedom of speech.

Definitely, if I’m ever offered 15 minutes of national TV time, I’m going to use it to complain that I don’t have freedom of speech.

What has happened here is that President Biden has stolen a trick from Trump, but implemented it in a cleverer way. Whenever the news cycle is going against Trump, he picks a fight with someone his base is inclined to hate: the Squad, or Colin Kaepernick, or LeBron James. The content of the fight doesn’t matter, and it doesn’t matter that Trump’s attack is usually unprovoked. Trump just knows that a fight between him and AOC plays well to his base. (Ron DeSantis is doing the same thing now: It doesn’t matter that he’s totally in the wrong about Black history or banning LGBTQ books. DeSantis vs. Black or gay or trans activists is a good look for him as he gets ready for the 2024 Republican primaries.)

So Biden comes out of the SOTU with Marjorie Taylor Greene yelling “Liar!” at him for saying something true and reasonable that she didn’t like. It’s a good look for him — not just in front of the progressive base, but in front of the American people.

[1] A point sometimes made by this blog’s commenters is that Social Security and Medicare have their own taxes and trust funds, and so are not technically part of the deficit. However, current estimates say that the Social Security trust fund runs out of money in 2035, and Medicare runs dry in 2028. If there are no tax increases by then — something Republicans always assume — either benefits are cut at that point or money to pay for them has to come out of the general fund.

Budget bills are only binding on the current year, but they typically project ten years ahead. A perennial Republican goal is to pass a budget bill that sees the annual deficit go away in the final year the 10-year window. So while the problem with Social Security is still over Congress’ horizon, the projected Medicare shortfall is relevant.

[2] There’s actually quite a list.

You know, we’re often told that Democrats and Republicans can’t work together. But over the past two years, we proved the cynics and naysayers wrong.

Yes, we disagreed plenty. And yes, there were times when Democrats went alone.

But time and again, Democrats and Republicans came together. Came together to defend a stronger and safer Europe. You came together to pass one in a once-in-a-generation infrastructure law building bridges connecting our nation and our people. We came together to pass one the most significant laws ever helping victims exposed to toxic burn pits.

And in fact, I signed over 300 bipartisan pieces of legislation since becoming President, from reauthorizing the Violence Against Women Act to the Electoral Count Reform Act, the Respect for Marriage Act that protects the right to marry the person you love.

[3] An aside: This back-and-forth, where Biden interacted with his opponents off-the-cuff — and ate their lunch in the process — should permanently put to rest all the nonsensical claims that Biden has dementia and is just reading words off a screen.

The political scientist most connected with this idea is Stephen Skowronek, who introduced the concept of “

The political scientist most connected with this idea is Stephen Skowronek, who introduced the concept of “