Right-wing policies have obvious victims, but right-wing voters can’t be allowed to notice them. This week, reports of a pregnant 10-year-old brought out the full arsenal of denial.

In the TV version of Westworld, the robots — or “hosts” in the corporate vernacular of the eponymous wild-west theme park — aren’t supposed to realize that they are manufactured pieces of an inauthentic environment. During each post-repair reactivation cycle, they are asked: “Have you ever questioned the nature of your reality?” If the answer seems to be drifting towards “yes”, more tinkering is needed.

Fail-safes are built into their programming. Evidence of the world beyond the park, or of their own artificiality, isn’t supposed to register. “That doesn’t look like anything to me,” says one host as she examines a color photograph anachronistically dropped by a “guest”. Much later, another host says the same line while holding his own blueprints [spoiler].

No victims. The political fantasy world of American conservatives has similar safeguards. Conservative policies have certain obvious victims, people whose undeserved hell stems directly from those policies. But the voters who support those policies are not supposed to notice.

Kids who go hungry or become homeless when social programs are cut? Neighbors of poorly regulated industrial sites who develop bizarre cancers? Communities destroyed by climate-change-induced wildfires? They don’t look like anything, do they? Conservative policies work out best for everybody, other than a few corrupt and power-hungry Democratic politicians, or lazy people of color who want to sponge off the hard work of real Americans (or, conversely, to steal their crappiest jobs). Why would you ever question the nature of that reality?

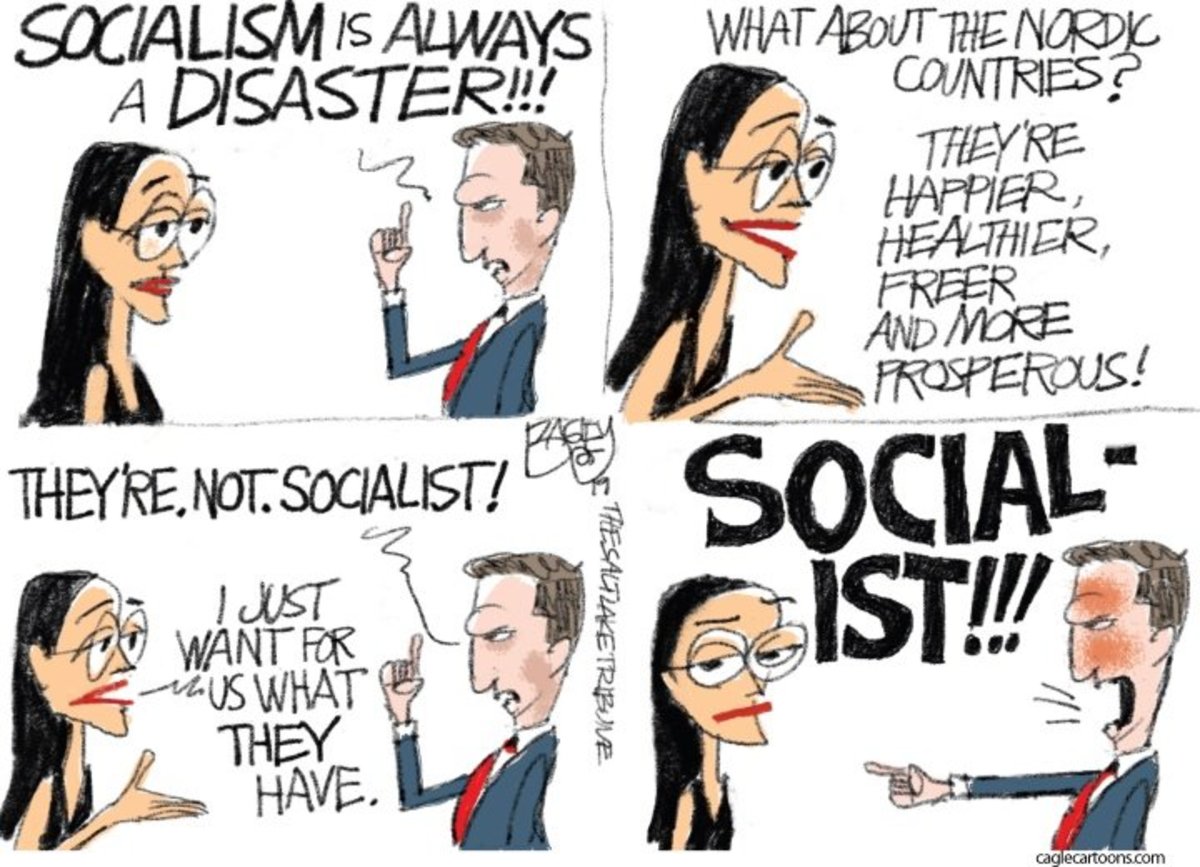

Usually, right-wing media filters narrative-busting facts out of the news stream before they can disturb right-wing voters’ peace of mind. Has the January 6 Committee proved beyond the shadow of doubt that Trump knew his “stolen election” claims were lies? Fox News will protect its viewers from seeing that evidence. Does the Biden administration have the best job-creation record in the history of the modern presidency? Are vaccinated-and-boosted Americans 17 times less likely to die of Covid than unvaccinated Americans? Does right-wing political violence kill many, many more people than left-wing political violence? Do countries with national health care have lower expenses and higher life expectancies than the US? Nobody wants to hear that stuff; just leave it out.

School shootings. Every few weeks, though, something happens that is too big for the filter to handle, like a school shooting. The connection to policy couldn’t be clearer: Children are dead because the shooter had easy access to weapons that should only exist on a battlefield. Democrats would like to ban or restrict or control such weapons, but conservatives have blocked restrictions, and have even pushed to make such weapons more ubiquitous.

Republican lawmakers and judges have innocent blood on their hands.

That’s when you can see the conservative bubble’s immune system in its purest form. Some parts of it will tell you the apparent victims aren’t real. Those well-spoken kids from Parkland, the ones who survived their harrowing experience and became anti-gun activists? The reason they’re so articulate isn’t that Marjory Stoneman Douglas High did a good job educating them, it’s that they are “crisis actors” who weren’t present for the shooting at all. Similarly, the Sandy Hook parents didn’t really lose any children, they just participated in a “FEMA drill to promote gun control” [scroll down three pages to see text].

Nothing to concern yourself about. If those victims evoked a feeling of empathy, you can turn it off, because (like the hosts at Westworld) they’re just characters in a story, and not people at all.

Or maybe the events that disturb you are “false flag operations“. Remember the Las Vegas shooting, where one guy killed 60 concert-goers and wounded hundreds of others with multiple bump-stock-enhanced AR-15s? It wasn’t the kind of thing that’s bound to happen occasionally in a country with more guns than people. No, it was “the Islamic State and Antifa” carrying out a false-flag conspiracy “scripted by deep-state Democrats and their Islamic allies”. And the guy who responded to Trump’s “invasion” rhetoric by killing as many Hispanics as possible at a WalMart in El Paso? Antifa. Gotta be antifa.

The very act of connecting horrible events to conservative policies is itself illegitimate. Noting the clear cause-and-effect is “politicizing tragedy“. (Framing mass shootings as “tragedies” is an additional sleight-of-hand: Tragedies arise from inexorable Fate rather than human choices.) Learning from the Uvalde shooting that 18-year-olds should not be able to buy assault weapons is “politicizing” the deaths of children. Discussing gun policy “too soon” after a shooting disrespects the dead. (Oddly, though, it was never too soon to blame President Biden’s Afghanistan withdrawal for the deaths of 13 Marines. That could start immediately.)

Discussing other kinds of policy issues after a shooting is fine: mental health, video games, broken families, reinstating school prayer. The NRA’s politicians toss those topics into the post-shooting conversation the way radar-evading aircraft scatter reflective chaff. It’s never “too soon” to raise one of these issues, because (unlike guns) they’re not “political”. You can also propose “solutions” like armed teachers and schools with prison-like security, but not gun control.

The pregnant 10-year-old and Ohio’s laws. This week, though, we saw the clearest right-wing denial operation yet: the pregnant Ohio 10-year-old who had to leave the state to get an abortion.

Inside the conservative information bubble, the abortion issue is about healthy women with healthy fetuses who conceived their babies in wantonness and are killing them out of selfishness. If they didn’t want to raise a child, they shouldn’t have been so promiscuous. As right-wing mega-donor Foster Friess put it in 2012: “Back in my days, they used Bayer aspirin for contraceptives. The gals put it between their knees, and it wasn’t that costly.” More recently, Republican Congressman Greg Murphy of North Carolina defended the Supreme Court’s reversal of Roe with this gaslighting tweet: “No one forces anyone to have sex.“

So how did a 10-year-old get pregnant? Did she consent? Does that question even make sense? I mean, reasonable people can argue about exactly where to draw the age-of-consent line, and some teen-age girls are closer to adulthood than others born on the same day. But ten?

So it’s rape. I don’t need to know the details.

Somehow, her body managed to ovulate. But was it capable of carrying a fetus to term and giving birth without suffering long-term damage? What about psychological trauma? And after birth, what then? Would she be old enough to decide whether to keep the child, or would that choice be taken away from her too?

Then we come to Ohio’s “heartbeat law“, which was passed by the legislature and signed by Governor Mike DeWine in 2019. It blocks abortions after “cardiac activity” can be detected, which is said to happen at about six weeks. (“Cardiac activity” is a deceptive term, and intentionally so. No six-week fetus has a beating heart. To be blunt, the anti-abortion movement is full of liars. You shouldn’t believe what they say about heartbeats, fetal pain, risks related to abortion, post-abortion regret, or pretty much anything.)

At first courts blocked the law, because it blatantly contradicted the Roe/Casey interpretation of the constitutional right to privacy. But then the Dobbs decision reversed Roe, and that same evening Ohio Attorney General Dave Yost announced that the heartbeat bill was once again in force.

When the girl, whose name thankfully has not been released (we’ll see how long that lasts), showed up in the office of a child-abuse doctor, she was six weeks and three days pregnant. (I’m amazed she responded that quickly. A pregnancy that early is sometimes hard for an adult woman to spot, much less a girl with a strong temptation to think “This can’t be happening.”)

That doctor called a colleague in Indiana (which probably won’t get around to banning abortion until a special session of the legislature starts next Monday), and a non-surgical abortion was performed in Indianapolis.

Media firestorm. The Ohio girl quickly became a symbol of the heartlessness of abortion bans. Abortion bans aren’t just about “saving babies”, who would all live to be cute and fat and happy if only their mothers weren’t so self-centered. The bans also have victims.

Sometimes abortion bans inflict hellish experiences on women and girls who have no good options. Sometimes the baby survives only to live in terrible pain for a few months before dying anyway. Some women are not going to get the best treatment for their miscarriages, because that treatment can look like an abortion.

And the Ohio girl is not unique; such cases will come up again. Similar but less extreme cases come up every day.

In Ohio alone, 52 girls under 15 received an abortion in 2020 — an average of one every week, according to the state Department of Health.

Abortion decisions are complicated, and each pregnant woman or girl who doesn’t want to become a mother has a unique story. That’s why I believe the decision should be left to the people involved rather than mandated by law.

In this particular case, the girl got an abortion before a long list of worse things could happen. But to a certain extent, that’s just the luck of timing. Indiana hasn’t gotten around to passing a heartbeat bill (or some even stricter ban) yet. Republicans haven’t managed to ban abortion nationwide — but they’d like to.

So it’s perfectly fair to ask anti-abortion zealots, like Governor Kristi Noem of South Dakota, how she would like such cases handled. The question is not some kind of trap. And there are reasonable ways, short of supporting reproductive rights, to respond to the pregnant-10-year-old story. I can think of two off the top of my head.

- Anti-abortion politicians could make a more-good-than-harm argument. Sure, if we ban abortion, some 10-year-olds are just going to have to try to carry their rapists’ babies to term. Some women with difficult pregnancies will probably die because the law will keep doctors from intervening until it’s too late. Some women will die from unsafe illegal abortions. But think of all the babies we’re saving!

- They could admit that abortion is a complicated issue, and start crafting a longer list of exceptions to the bans, acknowledging that the life of the fetus is not the only consideration.

Either option, though, would involve admitting that abortion bans have victims. And Republicans can’t do that.

The counterattack. Instead, they unleashed the full arsenal of denial. The story first appeared on July 1, and for a while the filter held: Just don’t mention the story and it will eventually pass. But then President Biden referenced it on July 8, so something more was called for. That same day, PJ Media began casting doubt.

There are major problems and inconsistencies with this story that no one in Big Media noticed or cared about. First, where is the police report or the social services investigation into the rape of the child? Who will be held accountable for child rape and why isn’t that an issue in any of the reporting? I was unable to find any verified police investigation connected to this story. Another troubling fact is the source of this claim is one person: Dr. Caitlin Bernard, an abortionist and activist who is all over the media advocating for more abortions and unrestricted abortions.

Last Monday, the 11th, AG Yost went on Jesse Watters’ Fox News show to imply that the story couldn’t be true because his office hadn’t heard about it. “We don’t know who the originating doctor in Ohio was — if they even exist.” If any local police were investigating such a case, he claimed, he’d know about it, because that’s how well plugged-in he is.

The next day he went further.

Yost doubled down on that in an interview with the USA TODAY Network Ohio bureau on Tuesday, saying that the more time passed before confirmation made it “more likely that this is a fabrication.”

That opened the floodgates. With no new evidence beyond Yost’s statements, Tucker Carlson said definitively that the story was false.

Why did the Biden administration – speaking of lying – repeat a story about a 10-year-old child who got pregnant and then got an abortion or was not allowed to get an abortion when it turns out the story was not true.

The Wall Street Journal described the story as “fanciful” and “unlikely”, apparently because it concerned a victim “no one can identify” (as if the 10-year-old’s identity should be out there). It didn’t say the word “lie”, but attacked Biden for repeating an unverified story.

All kinds of fanciful tales travel far on social media these days, but you don’t expect them to get a hearing at the White House.

(I have a hard time not laughing out loud at that statement. Before January 20, 2021, just about every presidential speech contained “fanciful tales” about Covid miracle cures or immigrant crime or election fraud. But now that a Democrat is in the White House again, the WSJ has rediscovered its high standards for presidential truthfulness.)

Jonathan Turley wrote an article for the NY Post that was originally headlined (and promoted on Twitter as) “Activist Tale of a 10-year-old Rape Victim’s Abortion Looks Like a Lie” before somebody toned it down for the print edition.

Newsmax host Chris Salcedo labeled Dr. Bernard “a pro-abortion sicko” and called for her license to be suspended, while Ohio congressman Jim Jordan agreed that the story “looks like it may just be completely made up”. (Appearing on Fox Wednesday, Indiana’s attorney general announced an investigation into Dr. Bernard, who appears to have done nothing wrong. Her picture has been displayed on television, and according to a colleague, “The local police have been alerted to concerns for her physical safety.”)

At this point, everybody in the world is at fault except the people who passed Ohio’s monstrous abortion law and the Supreme Court that turned their monster loose on the world. Joe Biden, the “left-wing media”, Dr. Bernard — they’re the villains of the story. But think about it: Independent of whether this particular incident could be verified or not, these basic facts are undeniable:

- Girls as young as 10 sometimes do get pregnant.

- Many red-state abortion bans that are either already in place or pending in the legislature would force those children to carry their fetuses to term, unless and until that effort was about to kill them.

Those two facts by themselves should have lent credibility to the Ohio story: There was no need to make up such a tale, because it was bound to happen eventually; all you had to do is wait.

Truth can’t break through. Wednesday, the story turned out to be true. A 27-year-old man confessed to the rape, which had been reported to local police on June 22. DNA tests were underway. (I guess AG Yost isn’t as well plugged in to local law enforcement as he thinks.) Dr. Bernard filled out the appropriate paperwork. None of the things conservatives had been going on and on about had any basis in fact.

But none of them have apologized for their mistakes. Attorney General Yost’s response to the arrest did not even acknowledge the total irresponsibility of his previous statements:

We rejoice anytime a child rapist is taken off the streets.

But anyway, now that we know the story is true, can we finally talk about forcing 10-year-olds to have their rapists’ babies? No, no, of course not.

You see, the confessed rapist is Hispanic, so now this is the story:

Columbus police detective Jeffrey Huhn testified during Wednesday’s hearing that law enforcement does not believe that Fuentes is in the country legally.

Instantly, right-wing media has gone from outrage at the Left inventing the rape story to outrage at the illegal immigrants who are raping our children.

Why would Ohio try to force a 10-year-old to have her rapist’s baby? Conservatives will never, ever discuss that question, because even entering such a conversation might cause them to question the nature of their reality.

[1] This is an example of

[1] This is an example of  This meaning of bullshifting derives from the technical meaning of bullshitting, as described in 1986 by Princeton philosopher Harry Frankfurt in his seminal paper “

This meaning of bullshifting derives from the technical meaning of bullshitting, as described in 1986 by Princeton philosopher Harry Frankfurt in his seminal paper “

Sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild started studying the Trump base years before anybody knew they’d be the Trump base. In her book

Sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild started studying the Trump base years before anybody knew they’d be the Trump base. In her book