This week: census, environmental regulations, coal jobs

I. The census

What’s misunderstood about it: How can counting people be a partisan issue?

What more people should know: A lot rides on the census. The Census Bureau knows it gets the answers wrong, but Republicans have a partisan interest in not letting it do better. In 2020, it’s being set up to fail.

*

When the Founders wrote the Constitution, they knew the country was changing fast. New people were pouring into America — some coming by choice and others by force. If Congress was going to represent these people into the distant future, it would have to change as the country changed. So somebody would have to keep track of how the country was changing. That’s why Article I, Section 2 says:

The actual Enumeration shall be made within three Years after the first Meeting of the Congress of the United States, and within every subsequent Term of ten Years, in such Manner as they shall by Law direct.

Congress has implemented that clause by setting up the Census Bureau, which tries to count everyone in America in each year that ends in a zero. You can look at this as a rolling peaceful revolution: Via the census, states like Virginia and Massachusetts have gradually surrendered their founding-era power to new states like California and Texas.

No doubt you learned in grade school that counting is an objective process that produces a correct answer — the same one for everybody who knows how to count. But in practice, when a bunch of people count to 325 million, agreement starts to break down. Now imagine that you’re counting a field full of 325 million cats, most running around and jumping over each other, and a few actively hiding from you. How do you come up with an answer you have faith in?

That’s the Census Bureau’s fundamental problem: Americans won’t stand still long enough to be counted, and some are actively suspicious of anybody from the government who comes around asking questions. Inevitably, then, not everybody gets counted, and some people get counted more than once. This is not a secret; the Census Bureau admits that it gets the wrong answer.

That might not be so bad if the errors were random, but they’re not. Basically, the more stable your life is, the more likely you are to be counted correctly. If, for example, you’re still living in the same house with the same people that a census worker counted ten years ago, they’re going to count you again. But if you’re sleeping on your friend’s couch for a few weeks while you’re waiting for a job to turn up, and thinking about moving back in with Mom if you can’t find one, then you might get missed.

Stability isn’t a randomly distributed quality. The LA Times spells it out:

The last census was considered successful — that is, the 2010 results were considered to be within an acceptable margin of error. But by the Census Bureau’s own estimates, it omitted 2.1% of African Americans, 1.5% of Latinos and nearly 5% of reservation-dwelling American Indians, while non-Latino whites were overcounted by almost 1%. The census missed about 7% of African American and Latino children 4 or younger, a rate twice as high as the overall average for young children.

But that raises an epistemological question: How do you know your count is wrong if you don’t have a correct count to compare it to? And if you have that correct count, why not just use it?

The answer to the first question is statistics. Imagine, for example, that you’re trying to count all the species that live in your back yard. You go out one day and count 50. Then you go out longer with a bigger magnifying glass and find 10 more. Then the next couple of times you don’t find anything new. But then you find two. Are you confident that’s all of them now? What’s your best guess about how many are really out there?

Now extend that to every yard in the neighborhood. Imagine that after each household does its own count, you all converge on one yard for a more intensive search than you’d be willing to do on every yard. That search finds even more new species. Now how many do you think you missed in the other yards?

Statisticians have thought long and hard about questions like that, and have a variety of well-tested ways to estimate the number of things that haven’t been found yet. If you apply those techniques to the census, you get more accurate estimates of the total.

So why not just use those estimates? Two reasons:

- It sounds bad: Ivory-tower eggheads are using a bunch of mumbo-jumbo Real Americans can’t understand to invent a bunch of blacks and Hispanics that nobody has ever seen.

- Republicans have a partisan interest in keeping the count the way it is.

The Census determines two very important things: how many representatives (and electoral votes) each state gets, and how hundreds of billions of dollars in federal money for programs like Medicaid and highway-building get distributed among the states. The miscount gives more power and money to mostly white (and Republican) states like Wyoming and Kansas, and less to a majority non-white (and Democratic) state like California. Within a state, Republican gerrymandering works by crowding Democratic-leaning urban minorities into a few districts, leaving a bunch of safely Republican rural and suburban districts. That minority-packing is even easier to do if a chunk of those people were never counted to begin with.

The 2020 census is already headed for trouble. The Census Bureau is being underfunded, taking no account of the fact that it has more people to count than last time. Plans to modernize its technology went badly. And it is currently leaderless: The bureau chief resigned at the end of June, and Trump has nominated no one to replace him.

So we’re set up for an even bigger uncount of minorities this year. And that’s got to make Paul Ryan happy.

II. Environmental regulations

What’s misunderstand about it: Many people believe that a clean environment is a costly luxury.

What more people should understand: Externalities. That’s how well-designed environmental regulations can save more money than they cost.

*

Nobody should come out of Econ 101 without an understanding externalities — real economic costs that the market doesn’t see because they aren’t borne by either the buyer or the seller.

Pollution is the classic example: Suppose I run a paper mill, and I use large quantities of chlorine to make my paper nice and white. At the end of the process I dump the chlorine into my local river, because that’s the cheapest way for me to get rid of it. Because I use such an inexpensive (for me) disposal process, I can keep my prices low. That makes me happy and my customers happy, so the market is happy too. Any of my competitors who doesn’t dump his chlorine in the river is going to be at a disadvantage.

The problems in this process only accrue to people who live downstream, especially fishermen and anybody who wants to swim or eat fish. They suffer real economic losses — losses that are probably much bigger than what I save. But since their loss is invisible to the paper market, nothing will change without the some outside-the-market action — like a government regulation, a court order, or a mob of fishermen coming to burn down my mill.

The problems in this process only accrue to people who live downstream, especially fishermen and anybody who wants to swim or eat fish. They suffer real economic losses — losses that are probably much bigger than what I save. But since their loss is invisible to the paper market, nothing will change without the some outside-the-market action — like a government regulation, a court order, or a mob of fishermen coming to burn down my mill.

Now suppose the government tells me I have to stop dumping chlorine. I have to find either some environmentally friendly paper-whitening technique or a way to treat my chlorine-tainted wastewater until it’s safe to put back into the river. Either solution will cost me money, and I will have no trouble calculating exactly how much. So you can bet there will be an article in my local newspaper (which now has to pay more for the newsprint it buys from me) about how many millions of dollars these new regulations cost. The corresponding gains by fishermen, riverfront resort owners whose properties no longer stink, and downstream towns that don’t have to get the chlorine out of their drinking water — that’s all much more diffuse and hard to quantify. So the newspaper won’t have any precise number to weigh my cost against. Chances are its readers will see the issue as money vs. quality of life. They won’t realize that the regulations also make sense in purely economic terms.

That’s an abstract and somewhat dated example, but similar issues — and similar news stories — appear all the time. The costs of new regulations are borne by specific industries who can calculate them exactly, while the benefits — though very real — are more diffuse, and may accrue to people who don’t even realize they’re benefiting. (Companies are very aware of what they’ll have to spend to take carcinogens out of their products, but nobody ever knows about the cancers they don’t get.) But that doesn’t mean that the benefits aren’t bigger than the costs, even in dollar terms.

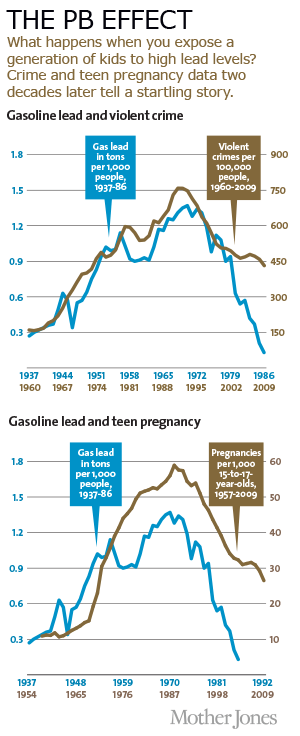

The best example from my lifetime is getting the lead out of gasoline. If you were alive at the time, you probably remember that the new unleaded gasoline cost a few cents more per gallon. Spread over the whole economy, that amounted to billions and billions. What we got out of that, though, was far more than just the vague satisfaction of breathing cleaner air. Without so much lead in their bloodstreams, our children are smarter, less violent, and less impulsive. The gains — even in purely material terms — have been overwhelmingly positive.

III. Coal jobs.

What’s misunderstood about it: What happened to them? Environmentalists are often blamed for destroying these jobs.

What more people should know: No doubt environmentalists would kill the coal industry if they could. But the real destroyers of coal jobs are automation and competition from other fuels.

*

Coal miners are the heroes of one of the classic success stories of the 20th century. Mining was originally a job for the desperate and expendable, but miners were among the first American workers to see the benefits of unionization. Year after year, coal mining became safer [1], less debilitating, and better paying, until by the 1960s a miner no longer “owed his soul to the company store“, but could be the breadwinner of a middle-class family, owning a home, driving a nice car or truck, and even sending his children to college. Sons and daughters of miners could become doctors, lawyers, or business executives. Or if they wanted to follow their fathers into the mines, that promised to be a good life too.

However, the total number of coal-mining jobs in the United States peaked in 1923.

Was that because Americans stopped using coal? Not at all. Coal production kept going up for the next 85 years.

Was that because Americans stopped using coal? Not at all. Coal production kept going up for the next 85 years.

The difference was automation. Mines employed three-quarters of a million men in the pick-and-shovel days, but better tools allow 21st-century mines to produce more coal with far fewer workers.

The difference was automation. Mines employed three-quarters of a million men in the pick-and-shovel days, but better tools allow 21st-century mines to produce more coal with far fewer workers.

If you take a closer look at that employment graph, you’ll notice a hump in the 1970s, when coal employment staged a brief comeback. That corresponded to the Arab Oil Embargo of 1973 and the increased oil prices of the OPEC era. For decades after that, coal was the cheaper, more reliable energy source. Americans who dreamed of energy independence dreamed of coal. In a 1980 presidential debate, candidate Ronald Reagan said:

This nation has been portrayed for too long a time to the people as being energy-poor, when it is energy-rich. The coal that the President [Carter] mentioned — yes, we have it, and yet 1/8th of our total coal resources is not being utilized at all right now. The mines are closed down. There are 22,000 miners out of work. Most of this is due to regulation.

However, all that changed with the fracking boom. Depending on market fluctuations, natural gas can be the cheaper fuel. Meanwhile, the price-per-watt of renewable energy is falling fast, and is now competitive with coal for some applications. So if a utility started building a new coal-fueled plant now, by the time it came on line a renewable source might be more economical — even without considering possible carbon taxes or environmental regulations.

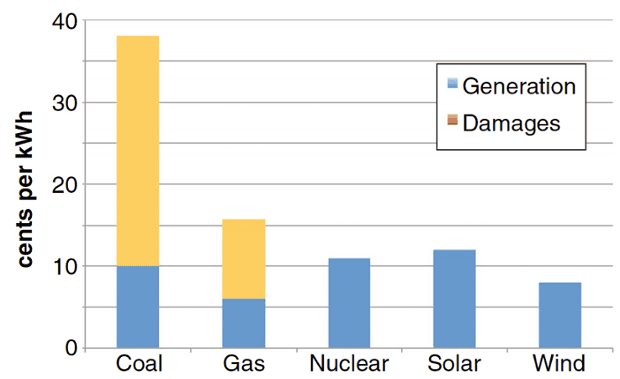

The dirtiness of coal is a huge externality (see misunderstanding II, above), so regulations disadvantaging it make good economic sense. Looking at the full cost to society, coal is the most expensive fuel we have, and should be phased out as soon as possible.

Statements like that make good fodder for politicians (like Trump or Reagan) who want to scapegoat environmental regulations for killing the coal industry. However, dirty coal is like the obnoxious murder victim in an Agatha Christie novel: Environmentalists are only one of the many who wanted it dead, and other suspects actually killed it.

Statements like that make good fodder for politicians (like Trump or Reagan) who want to scapegoat environmental regulations for killing the coal industry. However, dirty coal is like the obnoxious murder victim in an Agatha Christie novel: Environmentalists are only one of the many who wanted it dead, and other suspects actually killed it.

[1] The number of coal-mining deaths peaked at 3,242 in 1907. In 2016 that number was down to 8. As a comment below notes, though, that doesn’t count deaths from black lung disease, which are on the rise again.

Comments

Worth recalling that Anne Gorsuch, Neil’s mother and Ronald Reagan’s EPA administrator, tried to roll back those lead regulations. Some things never change. https://www.yahoo.com/news/news/trumps-supreme-court-pick-and-his-infamous-mother-012731939.html

I think the coal vs natural gas chart may be undercutting your message. The different vertical axis makes it difficult to read, but I think for the range covereged coal is pretty steady as about $2.50/MMBTU, while natural gas only briefly dropped that low, and is “predicted” (as of 2013) to stabilize around $4.00/MMBTU.

The Mother Jones lead charts have a similar problem. By offsetting the dates, at an initial read it looks like the crimes and pregnancies tracked lead almost instantly, which isn’t what you’d expect, and suggests a third factor. It takes a more careful reading to notice that the date ranges are offset by 23 and 17 years for the two charts.

(The Weekly Sift, come for the thoughtful, insightful analysis, stay for some rando in the comments complaining about charts.)

Sharp eyes. I should have noticed the two scales.

I’ve taken that chart out, and I’m looking to see if there’s other validation for the gas-is-cheaper claim.

Did you see this?

On Mon, Jul 24, 2017 at 9:16 AM, The Weekly Sift wrote:

> weeklysift posted: “This week: census, environmental regulations, coal > jobs I. The census What’s misunderstood about it: How can counting people > be a partisan issue? What more people should know: A lot rides on the > census. The Census Bureau knows it gets t” >

Even Mitch McConnell, KY-R, and Senate Majority Leader, admitted (after the election, natch) that coal jobs weren’t coming back to Eastern KY and that there was exactly nada that Republicans, or anyone else, could do about it.

https://thinkprogress.org/mcconnell-admits-jobs-war-on-coal-8938da18e5e3

Your footnote on deaths in coal mining does not account for deaths from Black Lung – once again on the rise.

That’s a good point. A good article on it is in Smithsonian. The cause of the upturn hasn’t been nailed down, but the article suggests that the decline of unions has made mines more brazen about skirting regulations.

Trackbacks

[…] adapted for the Trump family: “Fatherly Advice to Eric and Don Jr.“. This week’s three misunderstandings: the census, the economic impact of environmental regulations, and who killed the coal-mining […]

[…] blame onto well-chosen scapegoats is the heart of the Trump technique. Two weeks ago I described how environmentalists have been scapegoated for the decline in coal-mining jobs, taking […]