The people who run the global financial system are beginning to recognize that “the stability of the Earth system is a prerequisite for financial and price stability”.

Bankers are easy to demonize. They are generally more interested in money than in people, and when they do show interest in people, it’s usually not the ones who are poorest and most in need of concern. On the contrary, they often align with large corporate interests that squeeze profits out of anyone they can victimize.

In short, if you approach the world from a moral perspective, you will often find bankers on the wrong side of the issues you care about. (At least in their role as bankers. In private life some may, for all I know, vote Green and write checks to the Sierra Club.)

But no matter how often they side with the dark angels, bankers are not themselves demonic. They are not into evil-for-evil’s-sake, and (unlike certain religious sects) they would rather not hasten the apocalypse. They just look at the world through a particular lens, and moral concerns have to bounce off several distant mirrors before hitting that lens.

Stability. One thing bankers do value is stability. Morally, that is sometimes a bad thing; it’s why they can be friendly to tyrants and skeptical of even the most justified revolutions. (In the lead-up to the Civil War, for example, few bankers were abolitionists, even in the North. Slaves represented a huge amount of capital, which collectively collateralized loans of enormous dollar-value. What would happen to the economy if all those people suddenly belonged to themselves, rather than to the owners who had borrowed against their value?) But stability is also a mirror in which they can see the threat of climate change: What could be more unstable than a world going through a climate catastrophe?

This week the Bank of International Settlements (described by the NYT as “an umbrella organization for the world’s central banks”) put out a report: The Green Swan: central banking and financial stability in the age of climate change. A lot of that report is full of banker-speak and is hard for non-bankers to read. But nonetheless I think environmentalists would do well to pay attention, because central banks could become allies in certain fights if environmentalists learn how to talk to them and recruit them. (The same might be said of generals, because the Pentagon also recognizes the dangers of climate change).

Perhaps more importantly, a lot of powerful people who don’t trust environmentalists or care about polar bears do trust bankers and care about the risk of financial collapse. Quoting the BIS (or the subsequent reports I hope to see from the Federal Reserve or the European Central Bank) will carry more weight with such people than quoting Bill McKibben or a report from the Environmental Defense Fund. Learning the language financial people use to express their climate concerns could help mobilize a larger coalition.

Background: black swans. One thing you need to understand about serious central bankers and macro-economists is that the Great Recession shook their confidence. A lot of them look back on the 2007-2008 collapse and think “Who knew that could happen?” Risks that they had been modeling as independent variables turned out to be correlated in ways nobody expected. So when the dominoes started to fall, the chain reaction went much further than anyone would have predicted.

That experience has led to interest in what have become known as “black swan events“. Black swans are an old metaphor for a simple fallacy: If you see a large number of things that look very similar (white swans), you start to assume that something radically different (a black swan) is impossible. But in fact black swans do exist. The term was popularized in financial circles by Nassim Nicholas Taleb, who had the good timing to publish The Black Swan: the impact of the highly improbable in 2007.

The simple version of the black swan fallacy is that just because you’ve seen a lot doesn’t mean you’ve seen it all. You may feel confident because your data goes back 50 years, but what if there are catastrophic events that only happen every 100 years or 500 years?

The more complex version of the black swan fallacy is that statistical analysis often assumes that risk variables obey a normal distribution when the distribution actually isn’t known. That mistake can make extreme events seem far more improbable than they actually are. (When you hear statisticians talk about “long tails”, that’s what they mean.) Maybe something you’ve modeled as a once-in-500-years event is actually a once-in-40-years event that is overdue to happen.

Worse, there is a difference between risk and uncertainty. A risk is something that can be known and modeled. (A insurance company is taking a risk when it sells me life insurance, because I might die before I pay enough premiums to make them a profit. But the odds of a man my age dying in some particular future year are well understood.) Uncertainty is something you just don’t know. (Will Trump wind up in a war with Iran? How could you attach a number to that possibility?) Modeling something as a risk when it is actually uncertain can fool you into thinking you understand things much better than you do.

Green swans. One big problem climate-change activists have is that they are predicting things no living person has seen before. So rather than sober risk-managers, they can sound like religious fanatics. After all, somebody is always predicting the end of the world, and yet here we are.

We’ve seen a lot, so we think we’ve seen it all. And we’ve never seen Iowa turn into a desert or Miami get swallowed by the sea. (Until recently, though, we’d never seen Australia on fire either.) A very natural human response to such predictions is to say “That never happens.”

So the first challenge the BIS report has to overcome is its readers’ temptation to write the whole thing off as Chicken Littleism. That’s the point of its key image: the green swan. Green swans, like black swans, are unprecedented and largely unpredictable shocks to the system. But they don’t just surprise us because we’ve mis-estimated their probability; rather, they surprise us because we’ve entered new territory that we don’t really understand.

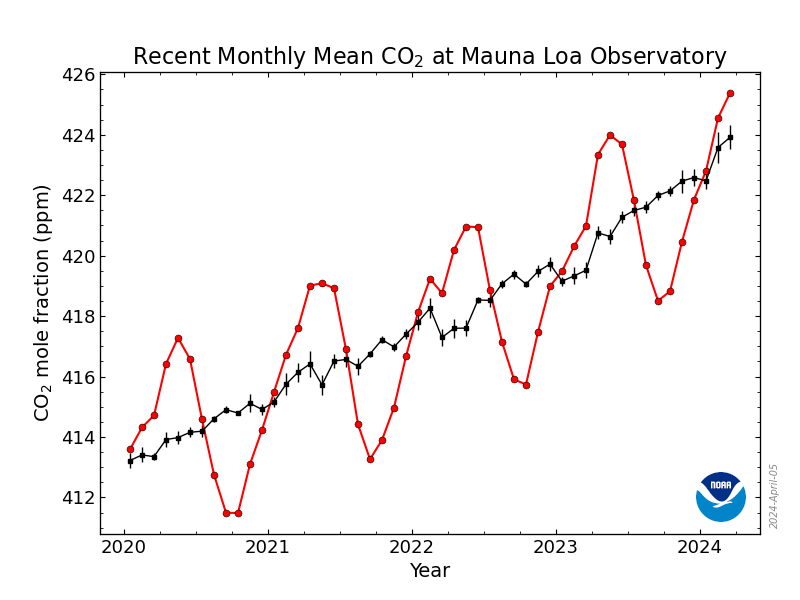

A green swan … is a new type of systemic risk that involves interacting, nonlinear, fundamentally unpredictable, environmental, social, economic and geopolitical dynamics, which are irreversibly transformed by the growing concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Climate-related risks are not simply black swans, i.e. tail risk events. With the complex chain reactions between degraded ecological conditions and unpredictable social, economic and political responses, with the risk of triggering tipping points, climate change represents a colossal and potentially irreversible risk of staggering complexity.

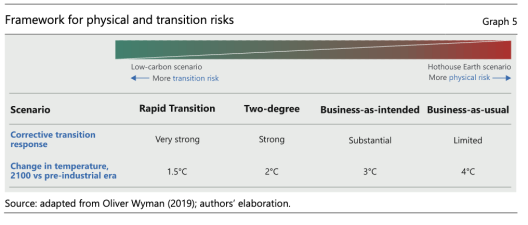

Two kinds of shocks to the system. Green swan events are of two major types: physical shocks and transition shocks. A physical shock is something that happens in the natural world: fire, drought, flood. Normally such things happen on a local scale that local systems can more-or-less take care of. But climate change could cause much larger physical shocks; for example, if a major ice sheet slid into the ocean all at once, raising sea levels suddenly rather than gradually. Think about this not from a human perspective, but from a central-bank perspective: Port facilities around the world all get wrecked at the same time; all the beachfront property in the world has suddenly dropped in value; banks that hold mortgages on that property are insolvent, as are insurance companies. As in the Great Recession, the financial dominoes start falling; you can’t pay me, so I can’t pay the other guy, and bankruptcies cascade to people and businesses nowhere near the ocean.

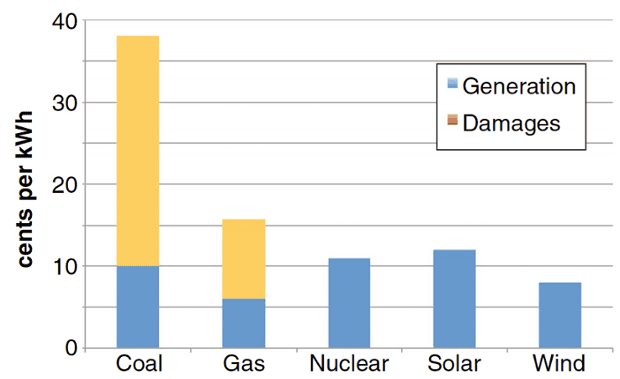

A transition shock is the market’s sudden revaluation of some class of assets, maybe because of a new government policy (like a carbon tax) or because some herd instinct causes investors to all change their minds at the same time. Dealing with climate change is going to involve revaluing a lot of assets. The biggest example is the value of fossil fuels still in the ground. Energy companies carry those assets on their books and value them at trillions of dollars. But if the world gets serious about climate change, most of those fuels will never be burned, so they’re not worth much at all. What happens to the world financial system if trillions of dollars of assets are suddenly worthless?

The two kinds of shocks trade off against each other: If we transition to a low-carbon economy quickly, we’ll see fewer physical shocks, but more transition shocks. If we move slowly, there won’t be so many transition shocks, but bigger physical shocks are coming.

The tragedy of the horizon. This is another bit of econo-speak that environmentalists can use. Every economist understands the “tragedy of the commons”, when a shared asset gets ruined because each individual can profit by overusing it.

So like “green swan”, the “tragedy of the horizon” plays off a well-understood concept. This time, the tragedy is that typical financial analysis happens on a timescale that minimizes climate effects. This is a “tragedy” because there’s no villain; financial analysis just isn’t trustworthy over long timescales, so practical people have learned to ignore it. (Example: Estimates of next year’s US federal budget deficit are usually pretty good, but nobody believes the ten-year estimate.)

This is what Mark Carney (2015) referred to as “the tragedy of the horizon”: while the physical impacts of climate change will be felt over a long-term horizon, with massive costs and possible civilisational impacts on future generations, the time horizon in which financial, economic and political players plan and act is much shorter. For instance, the time horizon of rating agencies to assess credit risks, and of central banks to conduct stress tests, is typically around three to five years.

One challenge the BIS report sets for the financial community, but does not solve itself, is how to overcome that tragedy. To appreciate the full scope of climate change, you have to look 50 or 100 years into the future. A climate plan that just tells us how to get by for the next ten years is all but useless. But how can that kind of thinking interact with models of inflation or unemployment or GDP that are pure fantasy at those timescales?

Epistemological breaks. A lot of the subtext of the report is that bankers are going to have to get used to living with uncertainty. Climate change is a large-scale multi-disciplinary problem that doesn’t lend itself to the kind of precise econometric modeling a central banker would like to see. (An unpredictable drought may cause an unpredictable migration of refugees and an unpredictable glut in the labor market of the sanctuary country.)

The term the report uses for this is the “epistemological break”. In other words: the way you’ve been thinking about things just doesn’t work any more. The kind of “knowledge” you’re looking for doesn’t exist.

The report calls for two epistemological breaks: First, to place less importance on predictive analysis based on past data (i.e., next year’s earnings estimates), and instead to stress-test against a variety of forward-looking scenarios (i.e., how would this bank do in case of a sudden jump in the cost of carbon emissions?).

[T]raditional approaches to risk management consisting in extrapolating historical data based on assumptions of normal distributions are largely irrelevant to assess future climate-related risks. Indeed, both physical and transition risks are characterised by deep uncertainty, nonlinearity and fat-tailed distributions. As such, assessing climate-related risks requires an “epistemological break” (Bachelard (1938)) with regard to risk management. In fact, such a break has started to take place in the financial community, with the development of forward-looking, scenario-based risk management methodologies.

And second, to be proactive in pushing both governments and the private sector to implement carbon-limiting policies.

Whereas they cannot and should not replace policymakers, [central bankers] also cannot sit still, since this could place them in the untenable situation of climate rescuer of last resort

Central bankers like to portray themselves as “above politics”, but they certainly express opinions about taxes and deficits; they should do so about climate policy as well. (The report regards some form of carbon tax or carbon pricing as a no-brainer. Governments should do at least that much.)

So what’s a central banker to do? Typical central banking picks up the pieces after disasters happen. That’s what banks and governments did after the Great Recession: bought up troubled assets and created a lot of new money to get economies rolling again.

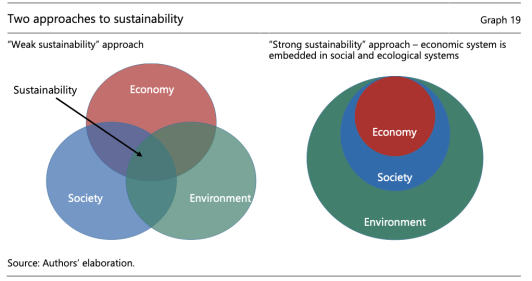

The report says that won’t work as a green-swan policy, because of the “limited substitutability between natural capital and other forms of capital”. In other words, if the Earth stops producing the stuff humans need to survive, giving people money won’t help. In a limited disaster, money allows the people affected to import resources from elsewhere. But in a global disaster, there is no elsewhere.

Central banks’ main power is in creating money and setting interest rates, but they also regulate the banking system, which in turn influences the companies the banks deal with.

The ways in which accounting norms incorporate (or not) environmental dimensions remains critical: accounting norms reflect broader worldviews of what is valued in a society (Jourdain (2019)), at both the microeconomic and macroeconomic level. From a financial stability perspective, it therefore remains critical to integrate biophysical indicators into existing accounting frameworks to ensure that policymakers and firm managers systematically include them in their risk management practices over different time horizons

The report (in some of its more technical passages, which may have gone over my head) proposes a number of ways central banks might use this power to change the economy as a whole. By defining new measures of sustainability and demanding that client banks report those measures, a central bank can alter the overall financial culture, with the result that “climate-related risks become integrated into financial stability monitoring and prudential supervision”.

[A] systematic integration of climate-related risks by financial institutions could act as a form of shadow pricing on carbon, and therefore help shift financial flows towards green assets. That is, if investors integrate climate-related risks into their risk assessment, then polluting assets will become more costly. This would trigger more investment in green assets, helping propel the transition to a low carbon economy (Pereira da Silva (2019a)) and break the tragedy of the horizon by better integrating long-term risks

Adding up to this:

Faced with these daunting challenges, a key contribution of central banks and supervisors may simply be to adequately frame the debate. In particular, they can play this role by: (i) providing a scientifically uncompromising picture of the risks ahead, assuming a limited substitutability between natural capital and other forms of capital; (ii) calling for bolder actions from public and private sectors aimed at preserving the resilience of Earth’s complex socio-ecological systems; and (iii) contributing, to the extent possible and within the remit of the evolving mandates provided by society, to managing these risks

What’s it mean for us? The direction of the world seldom changes all at once, and different sectors catch on at different rates. As different segments of society change their minds, it’s important to let them do so, and to encourage them. Each will have its own language for talking about its new ideas, and they can’t be expected to learn our language just because we got there first.

During the transition period, people whose worldview comes from that sector will have both the new frame and the old frame in their minds simultaneously, and either can be activated depending on how you approach them. (This is similar to what George Lakoff says about swing voters. It isn’t that they have a well-worked-out in-the-middle worldview; it’s that their minds contain both a liberal frame and a conservative frame. Depending on how they are approached, one frame or the other will be activated.) If you want to get such people on your side, it helps if you learn the language of their new frame and bypass obsolete arguments, rather than sticking with the old terminology and insisting on winning those arguments.

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/55234357/GettyImages_613835366.0.jpg)