Bret Stephens’ climate column serves one very important purpose: It illustrates Jason Stanley’s model of propaganda.

Few issues in American politics are as frustrating as climate change. It’s a real concern with potentially catastrophic consequences. The basic scientific description of the problem — burning fossil fuels increases the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, which warms the planet by blocking infrared radiation from escaping into space — is solid and hasn’t changed for decades. Every few years, the public seems to be getting energized about the problem, and it looks like we might finally get serious about taking action. But then we don’t.

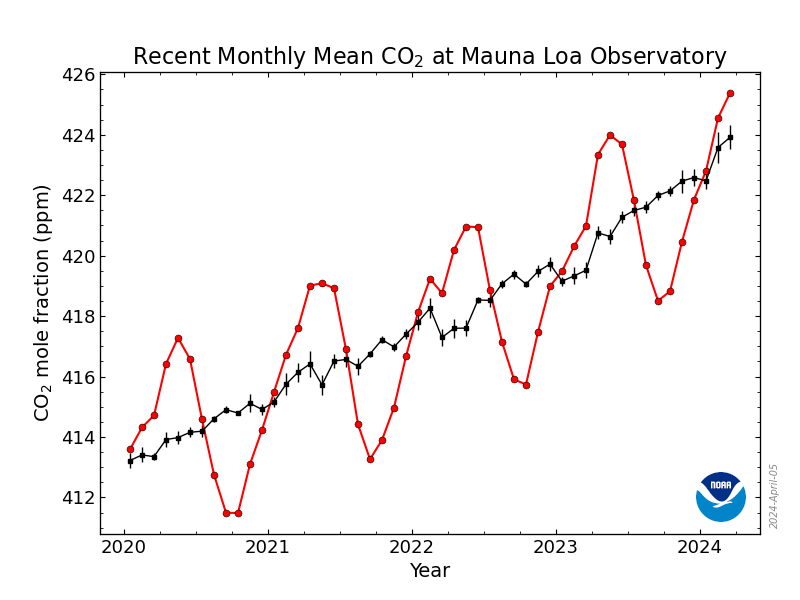

At the moment we’re in one of our hopeless phases, where science-deniers are in power and we have to focus on preserving what little progress we’ve made rather than building on it. Meanwhile, the clock is ticking. The level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere goes up every year. That’s not a conjecture or the result of some complicated computer model, it’s a measurement that gets made regularly by a NOAA laboratory on a mountaintop in Hawaii.

If the overall situation is frustrating in one way, attempting to change people’s minds about climate change is frustrating in a different way. You can go into an argument feeling that you have facts and logic on your side, and feel the same way afterwards, but at the same time realize that you didn’t convince anybody. Too often, environmentalists come out of a debate with a feeling of “What just happened?”

A good case in point was the discussion sparked ten days ago by Bret Stephens’ introductory NYT column “Climate of Complete Certainty“, which raised the specter of “overweening scientism” — radical environmentalists who claim 100% certainty for their predictions of global catastrophe and are “censoriously asserting [their] moral superiority and treating skeptics as imbeciles and deplorables”. The problem, in Stephens’ presentation, isn’t the scientists doing honest research on the climate, it’s the people pushing “ever harder to pass climate legislation” and “demanding abrupt and expensive changes in public policy”.

In many ways, the column was just another page from the science-denial playbook written in the 1970s by the tobacco industry: Emphasize the uncertainty of scientific findings, and from there argue that any action would be too hasty. We shouldn’t ban tobacco products, or restrict where smokers can light up, or put excessive taxes on cigarettes, or hold tobacco companies liable for public health problems, or even change our own individual smoking habits, because there’s still doubt. Of course we should take action once it’s been proven that tobacco causes cancer, but until the evidence is so conclusive that even the Tobacco Institute is convinced — which it never will be — we should wait and see. [1]

So Stephens isn’t anti-climate-research, he’s just criticizing the people who want to take action based on that research.

Or is he? There’s a puzzling vagueness to the column that made it very hard to argue against. Stephens didn’t name any of the “overweening” people who claim total certainty for uncertain things, or even identify what those claims are. The only specific example in the piece is a lengthy analogy that has no direct connection to the climate: the data-driven managers of Hillary Clinton’s campaign, who believed they were coasting to victory. They were wrong, so maybe the data-driven predictions of unnamed environmentalists are wrong too.

In other words, Stephens’ column is a very good example of that what-just-happened phenomenon. When I first read it, it seemed to be making some larger point that cried out for refutation. But the objectionable point had a vaporous quality; it didn’t seem to be contained in any particular sentence that I could quote and refute. Take this one for example:

Anyone who has read the 2014 report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change knows that, while the modest (0.85 degrees Celsius, or about 1.5 degrees Fahrenheit) warming of the earth since 1880 is indisputable, as is the human influence on that warming, much else that passes as accepted fact is really a matter of probabilities. That’s especially true of the sophisticated but fallible models and simulations by which scientists attempt to peer into the climate future.

Like a number of other critics, I might argue with the characterization of 1.5 degrees in 130 years as “modest” — until humanity started affecting in the climate, a change like that usually took millennia rather than decades — but overall, the statement is correct: It’s indisputable that we’re changing the climate, but it’s a lot iffier to predict exactly how fast that change will play out or which catastrophic events will happen when. For example, the land-borne ice sheets in Greenland or Antarctica might trickle slowly into the oceans and raise sea level over centuries, or one or more of them might suddenly slide into the water like an ice cube dropped into a glass of Coke. Nobody really knows.

Andrew Revkin, an environmental reporter that Stephens quotes admiringly (but who believes that “uncertainty, informed and bounded by science, is actionable knowledge” [2]), notes that changes in rainfall patterns are hard to predict: Some models show droughts in sub-Saharan Africa, while others foresee rainfall increasing.

I don’t have any trouble acknowledging that kind of uncertainty, and neither do most of the environmental writers I follow. So why do I feel like something Stephens’ column demands an argument?

What we’re seeing here is a masterful example of propaganda, as described in Jason Stanley’s How Propaganda Works, which I reviewed in 2015.

What we’re seeing here is a masterful example of propaganda, as described in Jason Stanley’s How Propaganda Works, which I reviewed in 2015.

If your target audience has a flawed ideology, then your propaganda doesn’t have to lie to them. The lie, in some sense, has already been embedded and only needs to be activated.

What’s being activated in Stephens’ column is a stereotype that Fox News, talk radio, and other conservative media has been drilling into its audience for years: Liberals don’t respect you. They look down on you, they think you’re stupid, and because they’re educated they think they can fool you with technical mumbo-jumbo that isn’t true.

That’s the point of talking about the Clintons and using words like deplorable. By doing so, Stephens invokes a previously successful application of the stereotype. You know the way you resent and distrust Hillary? You should feel that way about anybody who wants action on climate change.

It’s also the point of offering no other examples, and no examples at all from the environmental movement. Who does the stereotype apply to? Whoever you need it to apply to. If listening to Bill Nye or Bill McKibben makes you feel stupid, apply it to them. Al Gore, sure. Your niece who just got back from college, or that know-it-all at work, absolutely. Even real climate researchers like Jim Hansen and Michael Mann — the kind of scientists Stephens’ column seems explicitly not to criticize — can be lumped in if you need to.

If Stephens actually made a case against any of those people, that attack could be fact-checked and refuted. If he specified some particular prediction as over-the-top doomsaying, that prediction could either be defended or it could be demonstrated that the real leaders of the environmental movement do acknowledge the uncertainties involved. But a charge made with complete vagueness, one left hanging for its target audience to apply as it sees fit, can’t be answered in any logical way.

That’s how propaganda works. And in particular, that’s the way you will see propaganda appear in conservative columns in respectable mainstream outlets like The New York Times, or in public speeches by supposedly respectable politicians. The real dirty work has been done elsewhere. The lies and stereotypes have already been planted: Immigrants are criminals who endanger your family. Muslims want to take over America, not assimilate into it; and they all support terrorism whether they admit it or not. The poor are too lazy to work, but want you to support them anyway. Blacks are inferior and can’t really compete with whites, so they want the government to take your job and give it to them.

Anyone who wants to take advantage of such notions doesn’t have to state them in places where critics might demand evidence or poke holes in the argument. Like Bret Stephens, the propagandist just has to allude to them vaguely. The target audience will receive the message, and will enjoy the spectacle of opponents flailing vainly to refute what was never really said.

[1] The tobacco playbook and how it has been used in all sorts of controversies over the last half century has been described in two books I’ve reviewed here in the past: Merchants of Doubt and Doubt is Their Product.

[2] I wish he’d stated that in less complicated language, because it’s a point that needs more emphasis in the national debate, and doesn’t require any difficult scientific analysis.

In everyday life, we deal with uncertainty in two very different ways, depending on the circumstances. When we don’t know what might happen, sometimes we freeze until we do know. If, for example, you have a peanut allergy and you don’t know whether the salad the waitress brought you includes some peanut-derived ingredient, you don’t just eat it and hope you don’t wind up in the ER. You send the waitress to talk to the chef, and you don’t do anything until she gets back.

But in other situations, we respond to uncertainty by preparing for all plausible outcomes. When your child is born, you have no idea whether she’ll want to go to college or what college will cost in 18 years. But you don’t wait 16 or 17 years until you have a clearer idea of what she’ll need; if you do, it’ll already be too late to start saving. The prudent thing is to start that college fund as soon as you can, even though you can’t be 100% certain it’s necessary.

If you’re not sure whether you left the oven on, you don’t start preparing for the possibility that your house might be about to burn down; you stop everything and go home to check, or have someone else check. But if you’re not sure whether your department is about to have a round of lay-offs, you don’t freeze until you know for sure; you start getting your resume in order and checking the temperature of the job market, just in case.

This isn’t fancy research-scientist talk; this is how ordinary people live. Sometimes uncertainty freezes you; sometimes it springs you into action.

We’ve let the fossil-fuel lobby get away with the argument that on climate change, uncertainty should freeze us. (Nobody can tell us exactly when Miami will be underwater, so let’s not do anything.) But this point didn’t make sense when the tobacco industry used it — you can’t be sure cigarettes will give you cancer, so keep puffing away — and it doesn’t make sense now. Certainly that’s not how the Pentagon or the insurance industry is thinking about climate change; they’re planning to live in the future however it turns out, so they’re preparing for the possibilities.

That’s just common sense. Rising oceans, more violent weather, changes in rainfall patterns — these are more like your daughter’s college fund or the possible lay-off than like the salad dressing that might contain peanut oil: Even if they’re uncertain, they’re significant possibilities that we need to be preparing against. If there were some quick way to find out for sure what’s going to happen — asking the chef, checking the oven — maybe it would make sense to freeze and wait; but nobody’s come up with a way to do that, so our preparations have to move forward without that certainty.

Comments

As one cartoonist said, “what if we make the world a better place for nothing”

Kevin Drum nails Stephens’ 2nd column for a different deceptive technique. http://www.motherjones.com/kevin-drum/2017/05/new-york-times-has-imported-ethics-wall-street-journal

I learn so much from reading your articles. Your explanations help me to understand important concepts. Thank you. What can liberals do to fight the stereotypes Fox News and others drill into the minds of conservatives?

One idea: Each person picks one person/area/whatever to focus on. Maybe it’s somebody you know personally, or maybe you follow a conservative blog, or a local blog in a red state, or whatever works for you. Your role is to understand what’s in their heads well enough that you can present counter arguments that make sense *from their perspective*. I expect this to be hard. You’ll probably have to listen to a ton of stuff that makes no sense before you can even get close to a counter argument that make sense from their perspective.

That is a good idea. I live in a red state and have many conservative friends. I find I get too emotional when we talk about politics in person, but have been able to handle it better when writing. I think if both persons try to see the other person’s perspective, it works. I had one particular good exchange after a former colleague of my husband posted on Facebook that she hated “all Liberals” after reading an article by Garrison Keillor–you might remember the one that circulated last fall. I wrote to her privately that she was generalizing about all liberals. I didn’t think she really hated me, but reading her statement hurt. She wrote back and it helped me to understand how she felt. She said: “My frustration lies in many areas, one being… why is it okay for Liberals to shout their opinions from the rooftop, but a Conservative Christian should not because it means we are a racist, bigoted, LGBT hater. My Liberal facebook friends who post on Facebook act like I, and others like me, are stupid. We are uneducated, rednecks, who are too stupid to know any better. It gets so old. And in this particular article he was making fun. And I do believe most Liberals, or yes maybe extreme Liberals, feel the exact same way that Garrison Keillor. Again I apologize for offending you, but for me it has come down to, why can “they” say whatever they feel, but “we” can’t say what we feel.” (FYI: This person, a middle school teacher, has a master’s degree.) We continued to write back and forth, both apologizing. I often think about this exchange. You’re right. It was hard. I’ll keep your suggestion in mind. Thanks.

Trackbacks

[…] week’s featured posts are “Climate of Propaganda” and “Much Ado About Religious […]

[…] Climate of Propaganda […]