I. Armed civilians and tyranny

What’s misunderstood about it. One common argument in favor of private ownership of military-style weapons like the AR-15 is that a well-armed population is a necessary defense against tyranny, i.e., that the general population needs to retain the ability to overthrow the central government by military force. Ted Cruz has written that the Second Amendment serves as “the ultimate check against government tyranny — for the protection of freedom.”

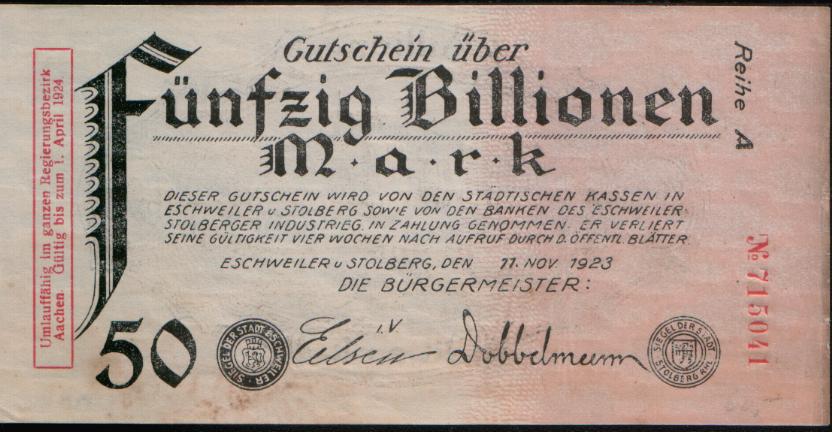

A parallel argument is that historically, dictators like Hitler disarmed the public before imposing full tyranny. Once disarmed, the argument goes, the people were as helpless as sheep. This Facebook meme is typical, and features typically misleading quotes.

Both quotes are doctored.

What’s wrong with that view? Just about everything.

Let’s start with Hitler. Salon’s Alex Seitz-Wald debunks “The Hitler Gun-Control Lie“, leaning on a more scholarly article by historian Bernard Harcourt. The 1938 gun law that NRA voices like Wayne LaPierre so often cite actually weakened the gun-control laws of the Weimar Republic.

The 1938 law signed by Hitler that LaPierre mentions in his book basically does the opposite of what he says it did. “The 1938 revisions completely deregulated the acquisition and transfer of rifles and shotguns, as well as ammunition,” Harcourt wrote. Meanwhile, many more categories of people, including Nazi party members, were exempted from gun ownership regulations altogether, while the legal age of purchase was lowered from 20 to 18, and permit lengths were extended from one year to three years.

The Hitler quote in the illustration refers not to German civilians, but to non-Aryans in occupied Russian territory. Obviously, he would not have referred to himself as a “conqueror” of the German nation, or to the Nazi master race as a “subjected people”.

If the NRA’s point were valid, you would expect the most democratic nations in the world to be the ones with the most guns, but if anything, the correlation runs in the opposite direction. Here are the four most democratic nations, according to the UK-based Economist Intelligence Unit.

| Nation | democracy index | guns per 100 civilians |

|---|---|---|

| Norway | 9.87 | 31.3 |

| Iceland | 9.58 | 30.3 |

| Sweden | 9.39 | 21 |

| New Zealand | 9.26 | 22.6 |

Even these gun-ownership numbers, I suspect, are exaggerated in comparison with the U.S., since they probably include very few weapons like the AR-15. (Norway’s parliament is reportedly ready to pass a complete ban on semi-automatic weapons, which would include a number of popular handguns as well as rifles.)

Here are the nations with the most guns in civilian hands.

| Nation | democracy index | guns per 100 civilians |

|---|---|---|

| United States | 7.98 | 101 |

| Serbia | 6.41 | 58.21 |

| Yemen | 2.07 | 54.8 |

| Cyprus | 7.59 | 36.4 |

Of particular note is Japan, where the average 100 civilians own a mere 0.6 guns, but whose democracy index on a par with the U.S.: 7.88. If a disarmed population is just asking for a totalitarian takeover, why isn’t one happening in Japan?

Switzerland and Israel are frequently cited as democratic countries with a large number of guns and little civilian gun violence, but in both countries possession of a gun is associated with military service, and is strongly regulated otherwise. The BBC quotes a Swiss gun-owner, who does not keep ammunition in his house and stores his gun’s barrel in a separate part of the house from its body:

The gun is not given to me to protect me or my family. I have been given this gun by my country to serve my country.

Finally, there are those quotes from the Founding Fathers like the one in the illustration above, nearly all of which have been either taken out of context, mis-attributed, or simply invented out of nothing. The Jefferson quote above is rejected on the official Monticello web site. Other frequently-cited fake quotes from the Founders are debunked at Guncite.com.

II. The original intent of the Second Amendment.

What’s misunderstood about it. It’s believed that the Founders passed the Second Amendment to protect an individual right to own militarily useful weapons (like, in our era, the AR-15), so that the People would have the ability to resist a tyrannical federal government.

What more people need to understand. That belief is historically baseless.

Legally, it doesn’t matter whether privately-owned weapons actually deter tyranny or not. (They don’t.) If the Founders believed they did, and wrote that belief into the Second Amendment, and if no generation since has seen fit to repeal it, then it’s the law. But that’s not what the Second Amendment is about at all.

At this point it’s worthwhile to look at the full text of the Amendment, which is short.

A well regulated Militia being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.

Today, we often tend to read right past the first clause and focus on the second. But it’s worth remembering what the Founders thought of when they saw the word militia: the Minutemen. In other words, a force of citizen-soldiers authorized by state or local governments, which could be called into action in a crisis. The current-day successor to the federal-era militias is the National Guard, not the self-appointed sovereign-citizen yahoos who drill up in the woods of Montana. The Constitution makes that quite clear in Article I, Section 8.

The Congress shall have Power … To provide for organizing, arming, and disciplining, the Militia, and for governing such Part of them as may be employed in the Service of the United States, reserving to the States respectively, the Appointment of the Officers, and the Authority of training the Militia according to the discipline prescribed by Congress.

The so-called militias we hear about today refuse to be organized, armed, or disciplined by Congress, or to be trained or have their officers appointed the states. So they’re not at all what the Constitution is talking about.

Why, then, was a well-regulated militia “necessary to the security of a free State”? Not so that it could fight against the federal government. In fact, Article I, Section 8 also explicitly gives Congress the power “to provide for calling forth the Militia”, which will then (Article II, Section 2) be under the command of the President. In case of insurrection, the Constitution foresees the militia fighting for the federal government, not against it.

The vision that worried the founding generation (enough to create the Second Amendment) was that the federal government might disband the militias and replace them with a large professional standing army, which would then need to have forts and bases throughout the country. Rather than repel an Indian raid itself, for example, a frontier community would have to call for help from the Army. Slave-owning states particularly worried about the possibility of an anti-slavery president refusing to put down a slave uprising (or maybe just dragging his feet). They wanted to be sure they would retain enough local power to keep their slaves under control.

Even more, the Founders feared that professional soldiers would grow to be loyal to their Commander in Chief rather than to the nation. The existence of this force might tempt a president to launch a coup and establish a military dictatorship. The point of a militia was to make that large permanent professional force unnecessary, not to fight pitched battles against it.

You can argue that we’ve already gone a long way down the road the Founders didn’t want us to travel: We have a large standing army with nationwide bases, and towns do not drill their citizens on the town green, as Lexington and Concord did. (However, we also have state and local police departments — which didn’t exist in the Founding era — so we’re not entirely dependent on the federal government for our security.) But self-appointed Rambos arming themselves to resist the federal government was no part of the Founders’ vision. The whole point of the Constitutional system was to allow for peaceful replacement of an unpopular government. As the Supreme Court wrote in 1951:

Whatever theoretical merit there may be to the argument that there is a “right” to rebellion against dictatorial governments is without force where the existing structure of the government provides for peaceful and orderly change.

III. The weapons the Second Amendment protects.

What’s misunderstood about it. Some Americans see virtually any restriction on the weapons they can own, or even registration of those weapons, as a violation of their Second Amendment rights.

What’s wrong with that? In the entire history of the United States, no court has understood the Second Amendment that way.

Given that the Second Amendment was part of the Bill of Rights passed by the first Congress, you’d expect all its major provisions to have a long history of judicial interpretation. But in fact the individual right to own specific weapons wasn’t recognized until the 2008 Heller case, a hotly contested 5-4 decision of the Supreme Court. Prior to that, courts construed the Amendment’s “right to bear arms” as a collective right belonging to “the People” as a whole, not individual persons. Historian Michael Waldman wrote:

“A fraud on the American public.” That’s how former Chief Justice Warren Burger described the idea that the Second Amendment gives an unfettered individual right to a gun. When he spoke these words to PBS in 1990, the rock-ribbed conservative appointed by Richard Nixon was expressing the longtime consensus of historians and judges across the political spectrum.

Until Heller, the Supreme Court’s landmark gun-rights case was Miller, in which it rejected the argument that the National Firearms Act (regulating sawed-off shotguns, among other weapons) violated constitutional rights. Even the Heller decision (written by the late Justice Antonin Scalia) doesn’t endorse the NRA’s view of the Second Amendment. It struck down a District of Columbia law banning handguns, while allowing that

Like most rights, the Second Amendment right is not unlimited. It is not a right to keep and carry any weapon whatsoever in any manner whatsoever and for whatever purpose.

Challenges to the Federal Assault Weapons Ban that was in force from 1994 to 2004 never made it to the Supreme Court, though the law was upheld by lower courts.

What today’s Court would do with an assault-weapons ban, or even a complete ban on semi-automatic weapons, is very much up in the air. Scalia’s Heller opinion found an expectation that the militia would assemble carrying weapons “in common use at the time” for legal purposes. How extensive that use needs to be was not specified. Whether AR-15s and other assault weapons are “in common use” would no doubt be hotly debated. Certainly they are not as widely used as handguns were in 2008, and the main legal purpose for which handguns were used (self-defense) carries more constitutional weight than the nebulous legal uses of assault weapons.

No court decision anywhere invalidates the government’s legitimate power to register weapons.

No court has rejected the federal ban on automatic weapons or the regulation of high explosives, so there is clearly a line somewhere between weapons that can and can’t be banned. The question would be which side AR-15s fall on.

Just to give one obvious example, it would be incredibly stupid for the government to allow people who live on the flight paths of major airports to own surface-to-air missiles. And yet, the argument that individuals have to be prepared to fight a tyrannical government would seem to justify those weapons. (How are we going to resist the government if we can’t take down its air power?) Those who believe the resist-the-government interpretation of the Second Amendment should be pushed to say whether any weapons can be banned or regulated, and why exactly such limitations are consistent with their theory.