In a democracy, the people shape their government. But in the long run, the government also shapes its people. What kind of citizens does a democracy need to have, if it’s going to sustain itself?

Back in the auspicious year of 1984, conservative pundit George Will published a book out of step with his era: Statecraft as Soulcraft. In those days, a popular liberal backlash to the rise of Jerry Falwell’s Moral Majority and its influence on the Reagan administration argued that government “can’t legislate morality”. Will countered that government not only can shape public morality, but it inevitably does whether it intends to or not. The “first question” of government, he claimed, is “What kind of people do we want our citizens to be?”

At the time, “legislating morality” evoked thoughts of controlling sexuality. (The Devil’s greatest trick, I remember telling someone, was to convince Christians that morality is primarily about sex rather than caring for others.) Persecuting homosexuals, banning abortion, cracking down on female promiscuity — those were the issues “moral” politicians seemed most concerned with. Later generations of social conservatives have argued that “the family” is the cornerstone of society, and so the traditional family must be protected against innovations like same-sex marriage.

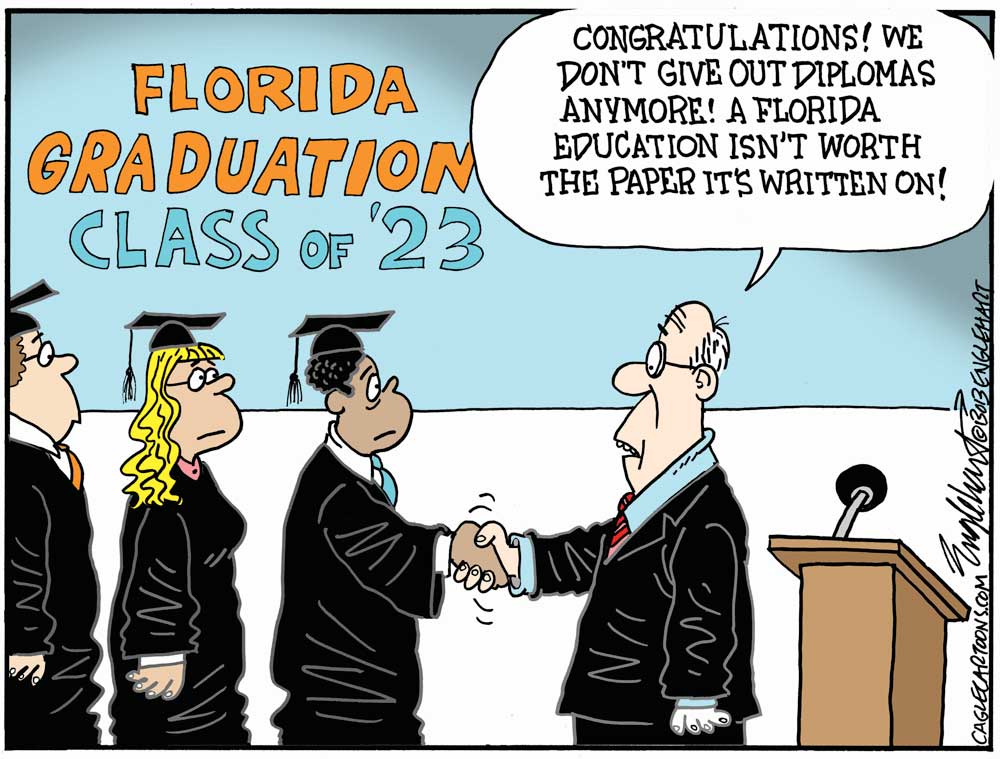

More broadly, “What kind of people do we want our citizens to be?” recalled Communist efforts to produce the “new Soviet man“, who would fit perfectly into the Soviet state, gladly foregoing personal fulfillment to help the dictatorship of the proletariat pursue the greater good. Similarly, an oligarchy might raise lower-class children to believe that they were better off being subjugated, or a Confederate-style slave republic might inculcate a sense of inferiority in Black people, so that they aspired to nothing higher than slavery. A North Korean-style cult of personality might raise children to hold the ruler in god-like awe.

Surely good Americans would want their government to stay far away from that kind of self-serving nurturance.

And yet, a democratic republic does require a certain kind of citizen. Government “of the people” assumes that the people have certain capabilities and virtues. In the long term, a democratic republic that doesn’t instill those capabilities and virtues will be unstable; it will preside over the destruction of its own foundation.

In the past, Americans have understood this. Universal public education became the law in one state after another precisely because of the fear that immigrant children would not understand democratic values, or learn to speak and read English, which was assumed to be the only possible medium for the public discourse democracy depends on.

This line of thinking came back to me this week when I read Mary Harrington’s “Thinking Is Becoming a Luxury Good” in the New York Times. The article had two main points:

- Smart phones and services like Tik-Tok are changing the way people (especially children) think, creating an easily distracted consciousness that looks for quick and amusing input without regard to accuracy. As a people, we are losing a more literate consciousness capable of “concentration, linear reasoning, and deep thought”.

- This tendency is more pronounced among poorer children, whose parents are less likely to insist on (and pay for) a more video-restrictive education.

Here’s the paragraph that brings the consequences home:

What will happen if this becomes fully realized? An electorate that has lost the capacity for long-form thought will be more tribal, less rational, largely uninterested in facts or even matters of historical record, moved more by vibes than cogent argument and open to fantastical ideas and bizarre conspiracy theories. If that sounds familiar, it may be a sign of how far down this path the West has already traveled.

Harrington compares Tik-Tok videos to junk food, and argues in favor of an “ascetic approach to cognitive fitness”. We used to say “you are what you eat”. Maybe the same thing works on the mental level: If you put garbage into your mind, garbage will come out.

As Cal Newport, a productivity expert, shows in his 2016 book, “Deep Work,” the digital environment is optimized for distraction, as various systems compete for our attention with notifications and other demands. Social media platforms are designed to be addictive, and the sheer volume of material incentivizes intense cognitive “bites” of discourse calibrated for maximum compulsiveness over nuance or thoughtful reasoning. The resulting patterns of content consumption form us neurologically for skimming, pattern recognition and distracted hopping from text to text

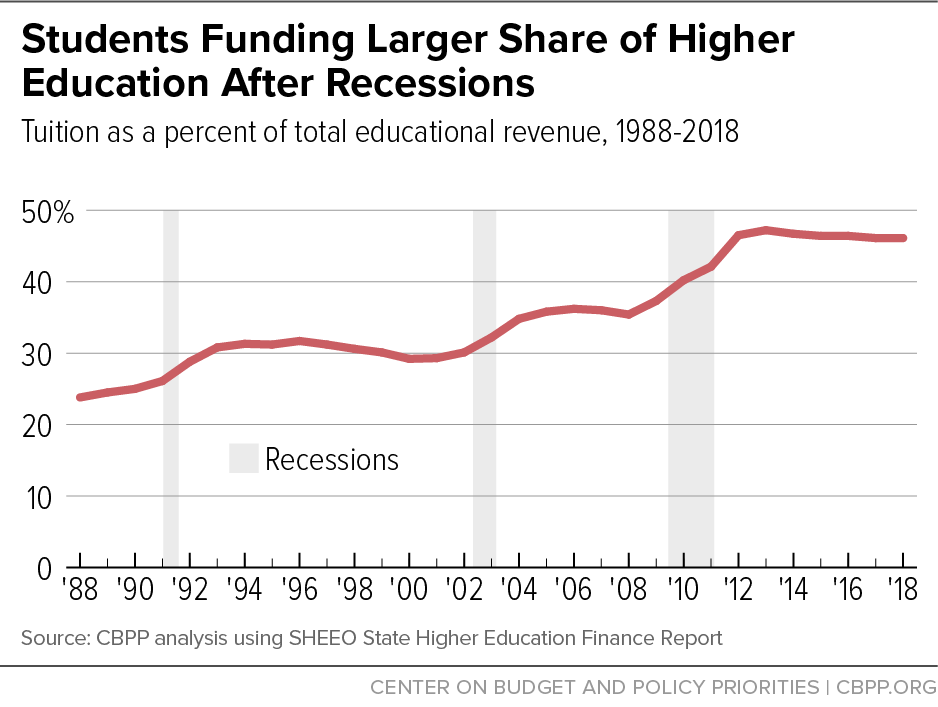

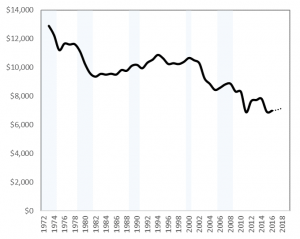

Like junk food, though, addictive-but-vacuous snippets of video are easier to obtain and harder to screen out than input that develops a deeper mind. More and more, it’s upper-class households that have the resources and the will to create an environment conducive to good cognitive development.

As Dr. [MaryAnne] Wolf points out, literacy and poverty have long been correlated. Now poor kids spend more time on screens each day than rich ones — in one 2019 study, about two hours more per day for U.S. tweens and teenagers whose families made less than $35,000 per year, compared with peers whose household incomes exceeded $100,000. Research indicates that kids who are exposed to more than two hours a day of recreational screen time have worse working memory, processing speed, attention levels, language skills and executive function than kids who are not.

Bluntly: Making healthy cognitive choices is hard. In a culture saturated with more accessible and engrossing forms of entertainment, long-form literacy may soon become the domain of elite subcultures.

Critics will argue that none of this is new. Older people (I’m 68) have always complained that younger people don’t think clearly, and have blamed new media and new technology for the change. Back in the early 1600s, Cervantes’ novel Don Quixote was in part a critique of what could happen to people who read too many of the cheap romances that Gutenberg’s printing press had made available: Their minds might fill up with fantastic notions disconnected from reality.

I grew up in a generation supposedly warped by comic books and (later) low-quality television. (I was exposed to a vast quantity of both. I can still sing the theme song of “My Mother the Car”.) Neal Postman’s 1985 book Amusing Ourselves to Death raised the specter of an electorate that chooses to be entertained rather than informed.

I also grew up in the working class (my father worked in a factory through most of my childhood, and neither of my parents went to college). So I have long been skeptical of studies supposedly proving that professional-class child-raising is superior to working-class child-raising. Too many well-born and well-educated sociologists have descended into working-class neighborhoods and seen the natives as a backward culture far inferior to themselves.

And yet … I came to literate culture with the enthusiasm of an immigrant. Arriving at a giant Big 10 university — an entire city about the size of my hometown, apparently devoted to discovering, recording, and passing down knowledge — was like entering the Emerald City of Oz. (I have never understood the ho-hum attitude that the children of my professional-class friends take towards college. Kids today approach Harvard with less awe than I had for Michigan State.)

Mathematics gave me an appreciation of truths that can’t be shaken by desire or popular opinion. Meditation taught me the virtues of a quiet mind, one that can let the waves of hype roll past until deeper thoughts emerge. (On the wall of my office is a painting of a young woman whose eyes are closed. She holds up one finger as a faint breeze begins to stir her hair. “Wait for it,” she seems to be saying.)

And so what particularly disturbs me about the present moment, beyond the rampant cruelty and the disregard of democratic traditions, is the impotence of rational thought, the inability of Truth to overtake Lie, and the lack of any deep engagement of mind with mind.

How can democracy survive this?

If the people are going to rule, then every child should be educated like an heir to the throne.

There has never been a democracy where the people were truly wise. But democracy rests on the belief that Truth has a persistence that eventually will win out. That’s why the Founders built so much delay into our system, particularly for fundamental changes like constitutional amendments. They recognized that momentary enthusiasms might sweep through the electorate. But over time, they believed, the cacophony of noises would cancel each other out, allowing the constant voice of reason to rise above the din.

But technology has raised the volume of noise. Somehow, we will have to produce a population that can think deeply anyway. That will require a new kind of soulcraft, one quite a bit deeper, I think, than George Will had in mind.

Sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild started studying the Trump base years before anybody knew they’d be the Trump base. In her book

Sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild started studying the Trump base years before anybody knew they’d be the Trump base. In her book  The University of Chicago, where I did my graduate work in the late 1970s and early 80s, doesn’t make headlines all that often. It’s been a top academic institution for more than a century, but hasn’t had a great sports team since

The University of Chicago, where I did my graduate work in the late 1970s and early 80s, doesn’t make headlines all that often. It’s been a top academic institution for more than a century, but hasn’t had a great sports team since