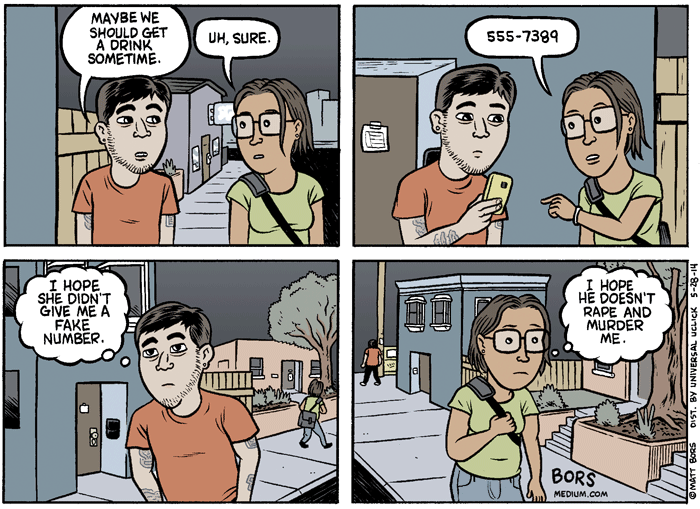

Men look at Elliot Rodger and say, “I would never do something like that.” Women look at his victims and say, “That could totally happen to me.”

Last week the Isla Vista murders — and Elliot Rodger’s bizarre rants justifying his revenge on the female gender because women wouldn’t have sex with him — were recent enough that I hadn’t processed them. I described my snap reaction as feeling “slimed”. Letting Rodger’s thoughts into my head just made me feel dirty, polluted, unclean. And I wrote, “I can’t imagine how women feel about it.”

This week women told the world how they feel about it. (They were already starting to tell the world last Monday, but I hadn’t discovered it yet.) I have read only a tiny fraction of what has been tweeted with the #YesAllWomen hashtag, but it has been eye-opening.

The struggle for meaning. Every striking news event starts a debate about what it means, or if it even means anything. For a lot of men, Isla Vista didn’t mean much: Crazy people do crazy things. Shit happens.

For others, it restarted the eternal gun-control debate, which always ends in the same place: Yes, a large majority of Americans want at least minor restrictions on guns, and no, it’s not going to happen, because America really isn’t a democracy any more. A victim’s father channeled the majority’s frustration in an interview with Anderson Cooper: “I don’t want to hear that you’re sorry about my son’s death,” he said to any politicians who might be planning to make a condolence call. “I don’t care if you’re sorry about my son’s death. You go back to Congress and you do something, and you come back to me and tell me you’ve done something. Then I’ll be interested in talking to you.”

Bizarre exception, or part of a pattern? To a lot of women, though, Isla Vista looked very different. Rather than a bizarre random event, it seemed like the extreme edge of the male aggression they experience constantly: They get grabbed or groped; men yell obscenities at them or make unwanted “flattering” comments about their bodies; they are harassed online; men demand their attention and refuse to go away; when women try to walk away, men grab their wrists or stand in the doorway or follow them as stalkers; men get angry and abusive when their uninvited advances are rejected; and on and on and on.

And while the exact statistics on rape are hotly debated — the difference depends in large part on how forcefully a woman has to say “no” before you count it — I have a lot of confidence in this qualitative statement: Just about every woman knows somebody who has been raped. (If you don’t believe me, ask some.) Whatever the definition is and whatever percentage that leads to, rape is not a monsters-in-the-closet phobia; it’s the well-founded fear that what happened to her (and maybe also to her and her and her) could happen to me.

So while men look at Elliot Rodger and say, “I would never do something like that”, women look at his victims and say, “That could totally happen to me.” Men divide the world into murderers and non-murderers, observing that the murderer pool is very small. Women look at murder as the extreme edge of a continuum of aggression, disrespect, and threat that affects them every day.

#YesAllWomen. And that is what I see as the point of #YesAllWomen: encouraging women to express and men to feel the oppressive weight of that continuum. #YesAllWomen is at its best when women simply tell their stories, one after another. Read enough stories and the bigger reality starts to break through: The meaning of Isla Vista isn’t that shit happens, it’s that the same kinds of shit keep happening day after day all over the country. And when there’s an widespread pattern like that, sooner or later it’s going to break out into something really horrific.*

The brilliance of #YesAllWomen is in its framing: It sidesteps the objection “Not all men are like that.” True or not, that objection misses the point. Whether or not feminist terms like misogyny or rape culture unfairly tar some good men is a minor issue compared to the environment of danger all women have to live in. Let’s not drop the larger issue to discuss the smaller one.**

And let’s not fall into the trap of interpreting every problem in the forest as the fault of individual trees. Laurie Penny explains:

of course not all men hate women. But culture hates women, so men who grow up in a sexist culture have a tendency to do and say sexist things, often without meaning to. … You can be the gentlest, sweetest man in the world yet still benefit from sexism. That’s how oppression works. Thousands of otherwise decent people are persuaded to go along with an unfair system because it’s less hassle that way. … I do not believe the majority of men are too stupid to understand this distinction

[And before we leave the gun-control issue entirely, can we discuss how the two issues interact? Think about the open-carry demonstrations in Texas or Georgia’s new guns-everywhere law. Now picture a woman you care about having a drink after work with some friends, and being accosted by a strange man who won’t go away. Now picture him armed. And no, NRA spokesmen, picturing a second gun in your sister/daughter/friend’s purse doesn’t fix the situation.]

The game. Men, by and large, have not handled our side of this discussion well, attempting either to disown the problem or to mansplain what women should do to fix it.*** But a few men have had intelligent things to say. I thought the Daily Beast piece by self-described nerd Arthur Chu was particularly on point:

[T]he overall problem is one of a culture where instead of seeing women as, you know, people, protagonists of their own stories just like we are of ours, men are taught that women are things to “earn,” to “win.” That if we try hard enough and persist long enough, we’ll get the girl in the end. Like life is a video game and women, like money and status, are just part of the reward we get for doing well.

The game metaphor explains a lot about what was wrong with Rodger’s point of view, and how it relates to a problem in the larger culture. Elliot Rodger’s complaint wasn’t that he couldn’t find his soulmate or that his genes might fail in the Darwinian struggle for immortality. It wasn’t even about pleasure, really, because you don’t need a partner for that. The essence of Rodger’s complaint was that he couldn’t level up — no matter how long he played or how hard he tried — in the multi-player game of sex.

To grasp the full dysfunction of that game, you need to understand who the players are: men. Rodger wasn’t playing with or even against women when he went out looking for sex. He was playing against other men to gain status. Women are just NPCs — non-player characters. Figuring out what to say or do to get their attention or their phone numbers or to get them into bed is like solving the gatekeeper’s riddle or finding the catch that opens the door to the secret passage.

Rodger’s virginity wasn’t just a lack of experience, comparable to someone who has never seen the ocean or been to Paris or tasted champagne. It was his state of being. He was a newby, a beginner, a loser. And it wasn’t fair. He had put so much of his time and effort and passion into the game; he deserved to get something out.

Chu explains the error:

other people’s bodies and other people’s love are not something that can be taken nor even something that can be earned—they can be given freely, by choice, or not.

We need to get that. Really, really grok that, if our half of the species ever going to be worth a damn. Not getting that means that there will always be some percent of us who will be rapists, and abusers, and killers.

What will we pass on? Phrasing the game metaphor in computer terms makes it sound like a new problem of the internet generation, but it’s not.**** Computer games are just a good way of describing an attitude that has been around since Achilles and Agamemnon argued over a slave girl: that women are just tokens in a competition among men. In junior high in the 70s, my friends and I talked about “getting to second base”, and today commercials sell Viagra and Grecian Formula to older men by telling us we can “get back in the game”. We all know what game they’re talking about.

As long as that attitude gets passed down from one generation of men to the next, there’s going to be an aggression-against-women problem. Because that’s how men play: You sneak some vaseline onto the ball, hide an ace up your sleeve, take that performance-enhancing drug, or push away a defender when the refs aren’t looking. If you can get away with it, it’s part of the game. So if it raises your score to grab some body part otherwise denied you, or to intimidate women into submission, take advantage of their unconsciousness, drug them, or even kidnap and imprison them, someone’s going to do it.

No one ever asks a boy whether he wants to play this game. At some point in your adolescence, you just find yourself in the middle of it, being told that you are losing and advised on how to win. There are competing visions that (for most men, I believe) eventually win out as they mature: the search for companionship, or looking for an ally to help you face life’s challenges. In those visions, women can be “protagonists of their own stories” rather than NPCs. But no one ever tells you there is a choice of visions and lays out the consequences.

If we did discuss these competing visions openly with boys, I don’t think the game metaphor would stand up to conscious scrutiny. Few men would openly defend the idea that women exist to be tokens of our competition, and even most teens already have enough empathy and experience for it to ring false. But the game attitude survives because we don’t bring it out into the light and discuss it.

Changing that dynamic would be a fine response to #YesAllWomen.

* I shake my head at the people who want to make an either/or out of whether the blame for Isla Vista belongs to a misogynistic culture or to Rodger’s personal insanity. Growing up, I had the chance to observe a paranoid relative. She went crazy during the McCarthy red scare, so the Communists were after her. If she’d broken with reality a few years earlier it might have been the Nazis; a few years later, the Mafia. Maybe people go crazy because their brains malfunction, but how they go crazy is shaped by their culture.

** One of the prerogatives of any form of privilege is that your concerns move to the top of the agenda, even if they are comparatively minor. Privileged classes of all sorts take this prerogative for granted and have a hard time seeing it as an injustice. So it is here: Men who feel smeared by a term like rape culture tend to think the conversation should immediately shift to their hurt feelings. It shouldn’t. To the extent that this objection is justified, it can wait. Let’s talk about it later. (Privileged classes aren’t used to hearing that response, but under-privileged classes hear it all the time.)

An important reason it should wait, in addition to its comparative insignificance, is that when a man fully grasps the continuum of aggression, it’s hard to claim that he’s never played any role in perpetuating it. (I know I can’t make that claim.) But by changing the subject to their own victimization, men avoid that realization.

*** Most advice about how to avoid rape — how to dress, places to avoid, not leaving your drink unattended — is really about making sure the rapist picks someone else. It’s like, “You don’t have to swim faster than the shark, you just have to swim faster than your sister.” It’s got zero impact on the overall rape problem.

**** And the attitude behind it is not even unique to men. In the pre-war chapters of Gone With the Wind, Scarlett is playing her own version of the game. While she wants to wind up with Ashley eventually, in the meantime she wants every eligible man in Georgia to be her suitor, and she “wins” whenever a bride realizes that she has married one of Scarlett’s cast-offs.

But there’s one important difference between the male and female versions of the game: Men who tire of Scarlett’s game can get on their horses and ride away, and in the end, it’s up to Rhett to decide whether or not he gives a damn. Women would like to have those options in the male version of the game.

Basketball player Jason Collins became the first active professional athlete in a major American sport to

Basketball player Jason Collins became the first active professional athlete in a major American sport to

In Self’s sequel, the Lion hosts the Kingdom Ball, to which mice are never invited, because they disgust many of the larger animals. Nothing personal, the Lion explains to his friend, it’s just the way things are.

In Self’s sequel, the Lion hosts the Kingdom Ball, to which mice are never invited, because they disgust many of the larger animals. Nothing personal, the Lion explains to his friend, it’s just the way things are.