The Atlantic published a much-discussed article about ISIS.

About half of it was deeply insightful.

What does the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria want? How is it different from al Qaeda? Why does it act the way it does? What are its leaders trying to do? What draws in Muslims from all over the world? And if we understood all those things, what strategy would we use to fight it?

Graeme Wood’s article “What ISIS Really Wants” in The Atlantic touched off a heated discussion of these important questions, and was answered by a flurry of other articles like “The Atlantic‘s Big Islam Lie” in Salon, “What The Atlantic Gets Dangerously Wrong about ISIS and Islam” in ThinkProgress, and many others. Just looking at the headlines might convince you that Wood’s article just touches off another he-said/she-said argument and isn’t worth the investment you’d need to figure out what it’s about.

That would be a mistake, because Wood’s article is a rare combination of deep insight with deep flaws. What’s even rarer, the insights don’t depend on the flaws. In other words, you can learn a lot from Wood about how Islam figures in the self-image and self-definition of the Islamic State, but avoid picking up Wood’s stereotyped view of Islam in general.

Let’s start with the insight. Wood raises two topics that hadn’t gotten much attention previously in the mainstream articles about ISIS, and makes a good case that they are highly significant in understanding the Islamic State:

- a particular Muslim vision of the end times

- ISIS’s leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi styling himself as a caliph who controls territory.

The End Times. Wood writes:

The Islamic State differs from nearly every other current jihadist movement in believing that it is written into God’s script as a central character. It is in this casting that the Islamic State is most boldly distinctive from its predecessors, and clearest in the religious nature of its mission. …

The Islamic State has attached great importance to the Syrian city of Dabiq, near Aleppo. It named its propaganda magazine after the town, and celebrated madly when (at great cost) it conquered Dabiq’s strategically unimportant plains. It is here, the Prophet reportedly said, that the armies of Rome will set up their camp. The armies of Islam will meet them, and Dabiq will be Rome’s Waterloo or its Antietam. … Now that it has taken Dabiq, the Islamic State awaits the arrival of an enemy army there, whose defeat will initiate the countdown to the apocalypse.

Students of Christianity will recognize the parallels to Megiddo, a.k.a. Armageddon, a site in Israel about twenty miles from Haifa. Like Armageddon, whose single sketchy reference in one verse of Revelation gets spun into Volume 11 of the Left Behind series, Dabiq is part of an elaborate projection of ancient prophecy onto current events.

Groups that see themselves playing a role in a prophesied Apocalypse (like ISIS) are different from predominantly political groups (like al Qaeda).

In broad strokes, al-Qaeda acts like an underground political movement, with worldly goals in sight at all times—the expulsion of non-Muslims from the Arabian peninsula, the abolishment of the state of Israel, the end of support for dictatorships in Muslim lands. The Islamic State has its share of worldly concerns (including, in the places it controls, collecting garbage and keeping the water running), but the End of Days is a leitmotif of its propaganda.

Apocalyptic groups have access to a higher level of fervor, but they are also more rigid. When the Americans brought overwhelming force to Afghanistan, Bin Laden could fold his tents and disappear. But if an enemy army really does show up at Dabiq, the Islamic State will have to fight it or face enormous loss of legitimacy.

The Caliphate. Bin Laden’s “franchised” terrorist movement had a highly flexible post-modern organizational structure. He envisioned a restored Caliphate as a distant goal, not something he might hope to rule (or even see) in his lifetime.

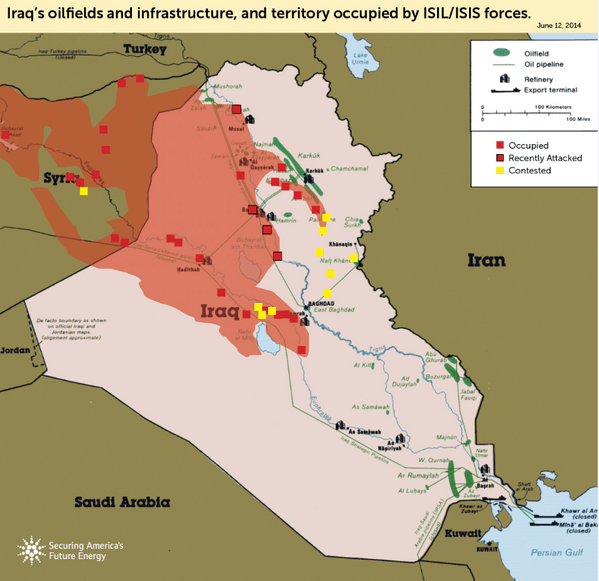

The Islamic State, by contrast, controls territory and has (according to Wood) “billboards, license plates, stationery, and coins”. At the moment that territory might amount to slivers of land nobody else wants badly enough to bleed for (see Wood’s map), but the fact that it exists — and that al-Baghdadi has been proclaimed Caliph of it — has enormous significance inside a particular interpretation of Sharia.

Wood quotes an Australian follower (whom the Australian government has been prevented from emigrating to the Islamic State):

Cerantonio explained the joy he felt when Baghdadi was declared the caliph on June 29—and the sudden, magnetic attraction that Mesopotamia began to exert on him and his friends. “I was in a hotel [in the Philippines], and I saw the declaration on television,” he told me. “And I was just amazed, and I’m like, Why am I stuck here in this bloody room?”

If there is a legitimate Caliph of Islam — like Popes and Highlander prize-winners, there can be only one — then all Muslims owe him allegiance.

Before the caliphate, “maybe 85 percent of the Sharia was absent from our lives,” Choudary told me. “These laws are in abeyance until we have khilafa”—a caliphate—“and now we have one.” Without a caliphate, for example, individual vigilantes are not obliged to amputate the hands of thieves they catch in the act. But create a caliphate, and this law, along with a huge body of other jurisprudence, suddenly awakens. In theory, all Muslims are obliged to immigrate to the territory where the caliph is applying these laws.

But maintaining control of that territory is part of the deal. A legitimate Caliph can’t just be the head of a franchised post-modern terror network, he has to control land and implement Sharia there.

So al-Baghdadi would lose his claim to the Caliphate if, like Bin Laden, he retreated to some equivalent of Tora Bora and then vanished. More than that: Islam would lose its Caliphate — which true Muslims have a duty to establish and maintain, according to Islamic State dogma — if it no longer controlled territory.

Dogma also puts restrictions on the kind of diplomacy ISIS can practice. In the long term, it is the duty of the Caliph to expand the Caliphate, so any treaties or boundaries established by treaties can only be temporary.

If the caliph consents to a longer-term peace or permanent border, he will be in error. Temporary peace treaties are renewable, but may not be applied to all enemies at once: the caliph must wage jihad at least once a year. He may not rest, or he will fall into a state of sin.

… It’s hard to overstate how hamstrung the Islamic State will be by its radicalism. The modern international system, born of the 1648 Peace of Westphalia, relies on each state’s willingness to recognize borders, however grudgingly. For the Islamic State, that recognition is ideological suicide. Other Islamist groups, such as the Muslim Brotherhood and Hamas, have succumbed to the blandishments of democracy and the potential for an invitation to the community of nations, complete with a UN seat. Negotiation and accommodation have worked, at times, for the Taliban as well. (Under Taliban rule, Afghanistan exchanged ambassadors with Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, and the United Arab Emirates, an act that invalidated the Taliban’s authority in the Islamic State’s eyes.) To the Islamic State these are not options, but acts of apostasy.

This territory-focus also makes its followers less immediately dangerous to the West: Staying in your home country and blowing things up is a second-best option. The higher goal is to move to the Islamic State and live under true Sharia.

During his visit to Mosul in December, Jürgen Todenhöfer interviewed a portly German jihadist and asked whether any of his comrades had returned to Europe to carry out attacks. The jihadist seemed to regard returnees not as soldiers but as dropouts. “The fact is that the returnees from the Islamic State should repent from their return,” he said. “I hope they review their religion.”

What ISIS implies about Islam. Where Wood goes wrong — and gets soundly thrashed for it in a number of articles — is in his framing of the nature of Islam — not just what it means to al-Baghdadi and his followers, but what it means in a more absolute sense. He begins by setting up the straw-man argument that the Islamic State is “un-Islamic” and then knocks it down like this:

Many mainstream Muslim organizations have gone so far as to say the Islamic State is, in fact, un-Islamic. It is, of course, reassuring to know that the vast majority of Muslims have zero interest in replacing Hollywood movies with public executions as evening entertainment. But Muslims who call the Islamic State un-Islamic are typically, as the Princeton scholar Bernard Haykel, the leading expert on the group’s theology, told me, “embarrassed and politically correct, with a cotton-candy view of their own religion” that neglects “what their religion has historically and legally required.” Many denials of the Islamic State’s religious nature, he said, are rooted in an “interfaith-Christian-nonsense tradition.”

TPM’s Josh Marshall reacted to the straw man with:

The Wood piece is a fascinating read. But did someone read this and think, Damn, these ISIS folks are really hardcore and they are seriously into Islam!

And Fareed Zakaria writes:

Wood’s essay reminds me of some of the breathless tracts during the Cold War that pointed out that the communists really, really believed in communism. [see endnote 1]

Wood’s (and Haykel’s) argument is a slight-of-hand that works by interchanging two meanings of Islamic. On the one hand, Islam is a tradition that begins with Muhammad and the Qur’an and continues through the centuries. In that sense, Wood’s claim that the Islamic State is “very Islamic” is true: ISIS arises out of one strand of interpretation of sources in the Islamic tradition. Few, if any, critics are claiming that ISIS’s religious fervor is simply a false face consciously wallpapered over secular intentions.

But Islam is also the spiritual practice of 1.6 billion people, each of whom has a unique perspective on the true spirit of the faith. When Muslims say that ISIS is “un-Islamic”, they mean that the religion they are in relationship with finds ISIS’s practices abhorrent. (It’s similar to the way you might react if a close friend were accused of a heinous crime: “The Bob I know would never do that.”)

An appropriate Christian analogy [2] would be the white-supremacist Christian Identity movement. Its rhetoric is incomprehensible without a detailed knowledge of the Bible, so it is very Christian in the sense that it grows out of the Christian tradition. But is it in harmony with the true spirit of Christianity? The vast majority of practicing Christians would say no.

And lest secularists think this is all some defect of religion, Soviet Communism is an inescapable part of the Western secular tradition. It billed its view of history as “scientific”, and its underlying philosophy of dialectical materialism was incomprehensible without reference to the secular Western concept of history as linear and conducive to progress.

There’s a lesson here: If you don’t want to take responsibility for everything that grows out of the roots of your own tradition, you don’t get to assign similar responsibilities to people from other traditions.

Seriousness. Wood’s article embodies an attitude I’ve criticized here and here: that only extremists are “serious” about their beliefs. Again he quotes Haykel, who attributes to ISIS “an assiduous, obsessive seriousness that Muslims don’t normally have.”

When you are the victim of this “seriousness” fallacy, the flaw is obvious: Communists are the only “serious” liberals and Fascists the only “serious” conservatives. If Martin Luther King had been “serious”, he would have demanded black supremacy rather than integration. Only the strictest Libertarians are “serious” about freedom. Have you ever based a decision on emotion or intuition? Ever appreciated a work of art or music without being able to explain why? Then you’re not “serious” about rationality. Would you fight against the rape of your daughter or take up arms to liberate Auschwitz? Sorry, but you’re really a war-monger at heart; only absolute pacifists are “serious” opponents of violence.

I could go on, but I hope I’ve given enough examples for you to find one that offends you.

Wood’s defeat of the ISIS-is-un-Islamic straw man leads him seamlessly into the implication that ISIS is where Islam goes if you are “serious” about it. Any tendency to co-exist with the modern world marks you as an un-serious Muslim, with a “cotton candy view” of Islam. [3] From a defense of the obviously true notion that the Islamic State is based on one interpretation of Islam, Wood segues to the dubious implication that it is the only “serious” interpretation.

Well, almost. Eventually, if you read far enough into Wood’s article, you get this caveat:

It would be facile, even exculpatory, to call the problem of the Islamic State “a problem with Islam.” The religion allows many interpretations, and Islamic State supporters are morally on the hook for the one they choose. And yet simply denouncing the Islamic State as un-Islamic can be counterproductive, especially if those who hear the message have read the holy texts and seen the endorsement of many of the caliphate’s practices written plainly within them.

He counters ISIS with another “serious” interpretation: one that also wants to recreate the 7th century, but has a personal rather than political focus.

These quietist Salafis, as they are known, agree with the Islamic State that God’s law is the only law, and they eschew practices like voting and the creation of political parties. But they interpret the Koran’s hatred of discord and chaos as requiring them to fall into line with just about any leader, including some manifestly sinful ones. … Much in the same way ultra-Orthodox Jews debate whether it’s kosher to tear off squares of toilet paper on the Sabbath (does that count as “rending cloth”?), they spend an inordinate amount of time ensuring that their trousers are not too long, that their beards are trimmed in some areas and shaggy in others. Through this fastidious observance, they believe, God will favor them with strength and numbers, and perhaps a caliphate will arise. At that moment, Muslims will take vengeance and, yes, achieve glorious victory at Dabiq. But Pocius cites a slew of modern Salafi theologians who argue that a caliphate cannot come into being in a righteous way except through the unmistakable will of God.

So those are your choices, Muslims: You can go to Dabiq, pledge allegiance to al-Baghdadi, and prepare to fight the Crusader invasion. Or you can spend your life avoiding politics, following sinful leaders, and worrying about the length of your trousers. Or, if you’d rather live in the 21st century, you can refuse to be “serious” and practice “cotton-candy” Islam.

Interpretation. Every useful insight Wood has about end-times prophecy or the Caliphate is compatible with the more common scholarly view that ISIS’s version of Islam is one interpretation among many. One writer who strikes that balance well is Hussein Ibish. As he said in an interview:

Neither is ISIS authentically Islamic, nor is it in any meaningful sense not Islamic. It is a bizarre interpretation of Islam yoked to a political agenda which is very modern. If we just stop fretting about the relationship of ISIS to the religious base of its ideology and accept that it’s a bunch of extremists who come out of a tradition that they manipulate to justify their crimes and their ambitions, it’s not so complicated.

Think Progress quotes Jerusha Tanner Lamptey, Professor of Islam and Ministry at Union Theological Seminary:

[Islamic] texts have never been only interpreted literally. They have always been interpreted in multiple ways — and that’s not a chronological thing, that’s been the case from the get-go.

Such interpretation is necessary, because (like any set of founding texts [4]), taking every line of the Qur’an as a truth that applies to every situation in the most obvious way leads to contradictions. Non-literal interpretation is also necessary for the Islamic State, because the Qur’an contains peaceful, merciful verses as well as violent, cruel ones.

ISIS exegetes these verses away I am sure, but that’s the point. It’s not really about one perspective being literal, one being legitimate, one ignoring things … it’s about diverse interpretations.

The various versions of Sharia — there’s not just one — are themselves interpretations that arose centuries after Muhammad. For example, all the Islamic State dogma about the significance of the Caliphate has to be post-Qur’anic interpretation for a very simple reason: In Muhammad’s day there was no institutional Caliphate; there was just Muhammad. (Similarly, the New Testament contains no mention of the Papacy. The institution-builders came later.)

Don’t give ISIS what it wants. There are two reasons we should try to understand ISIS: so what we can predict what it will do (and maybe even manipulate it to our advantage), and so that we don’t inadvertently give it what it wants.

Here are some things ISIS wants:

- To be seen as the only Muslims who take Islam seriously. Wood and many others are giving al-Baghdadi what he wants.

- To be Islam’s representative in an apocalyptic Islam-against-the-infidels holy war. So when Bill O’Reilly announces “The Holy War has begun.”, he’s endorsing ISIS’ narrative.

- Polarization. An essential aspect of the Apocalypse is that everybody has to pick a side. The worst thing for ISIS is to be viewed as nothing more than one bizarre splinter of Islamic interpretation. We should be encouraging other Muslims to ask: “So how’s that working out for you? Are you prosperous and thriving? Or have you turned your corner of the Earth into a little piece of Hell?”

- Drama. Jihadists come to the Islamic State looking to fight the ultimate battle. So the more boring we can make their lives, the harder it will be for them. Keeping ISIS bottled up inside its current boundaries may seem like no progress, but it may be the best strategy. The search for drama may lead ISIS to splinter into factions that fight each other over trivial doctrinal differences.

- To strike terror into the hearts of infidels. Whenever American pundits frame ISIS’ jihadists as the baddest baddies in the history of badness, they’re serving the ISIS propaganda effort. The reason ISIS has to keep racheting things up — from beheadings to burning people alive — is that they need to shock us. We should refuse to be shocked.

Face it on our terms. In the long run, al-Baghdadi can only succeed if he can create an economy based on more than just loot and ransom. That will be hard to do with the territory he has, so keeping him bottled up in it is a good strategy.

The United States military has two major advantages: First, we can bomb the hell out of any army that tries to mass and advance. That’s how we stopped the progress of ISIS towards Kirkuk and Baghdad, and in general how we can hope to keep it bottled up.

Second, our troops can win any pitched battle on open ground. Where we run into trouble is in the kind of guerrilla fighting where we can’t tell who the enemy is.

If the Islamic State doesn’t dissolve into frustrated splinters, we may someday need to fight that pitched battle on open ground. And unlike al Qaeda or the Taliban, ISIS will have a hard time avoiding it.

[1] It’s striking how closely current anti-Islam rhetoric tracks Cold War anti-Communist rhetoric. For example, here’s a Cold War quote from Ronald Reagan in the 1960s (lifted from The Invisible Bridge): “The inescapable truth is that we are at war, and we are losing that war simply because we don’t or won’t realize we are in it.” Compare this to Newt Gingrich discussing our current war with Islam: “You cannot win this war if you don’t admit that it’s a war.”

[2] Whenever people make such analogies, a linguistic problem shows up: Muslims have two adjectives — Muslim and Islamic — where Christians have only the adjective Christian. A Muslim is an imperfect human being who practices Islam. To say that something is Muslim means only that it is associated with Muslims. So Egypt is Muslim country, because you can expect to run into a lot of Muslims there.

But to Muslims, something is Islamic only if it is part of the religion of Islam, and there is a strong implication that it is a true part of Islam, since Islam is the true faith. So it would be inappropriate to say that Egypt is an Islamic country, unless you believe that the current military junta governs according to Allah’s true will.

Hence the controversy over the phrase Islamic terrorism. The Charlie Hebdo massacre was clearly Muslim terrorism, since the people who carried it out were Muslims. But to call it Islamic terrorism implies that the terrorists were faithfully serving Allah when they killed their victims. The terrorists themselves made that claim, but Muslims around the world disagreed. Those who describe the massacre as Islamic terrorism are implicitly taking the terrorists’ side in this argument.

[3] Sam Harris uses serious in a similar way: “There are hundreds of millions of Muslims who are nominal Muslims, who don’t take the faith seriously, who don’t want to kill apostates, who are horrified by ISIS.”

[4] As former Supreme Court Justice David Souter pointed out, the same is true of the Constitution. Interpretation is necessary because “the Constitution contains values that may well exist in tension with each other, not in harmony.”

There’s a whole other essay to write here, but traditional societies tend to govern themselves according to collections of contradictory aphorisms that serve to frame the community discussion of any particular case. (Is this a “look before you leap” situation, or a “he who hesitates is lost” situation?) That’s a system, not a flaw; it’s how timeless folk wisdom mixes with immediate circumstances. Only when you start using Enlightenment-style rationality and treating the aphorisms like Euclidean axioms do the contradictions become a problem.

One major theme of George Orwell’s

One major theme of George Orwell’s

I don’t how else to make sense of the fury that has been directed at Bowe Bergdahl

I don’t how else to make sense of the fury that has been directed at Bowe Bergdahl

The surveillance state is eating its own. In the post-privacy era of the Internet and the Patriot Act, the FBI has become the Eye of Sauron: Once its attention has been drawn to you, it will soon know your secrets and the secrets of all your associates, whether or not anyone has committed a crime.

The surveillance state is eating its own. In the post-privacy era of the Internet and the Patriot Act, the FBI has become the Eye of Sauron: Once its attention has been drawn to you, it will soon know your secrets and the secrets of all your associates, whether or not anyone has committed a crime.