Every previous president since Pearl Harbor would have handled the Soleimani announcement very differently.

It’s now been ten days since the United States assassinated top Iranian General Qasem Soleimani near the Baghdad airport, and we still have no coherent explanation of why it was done, why it was legal, and what strategy the assassination is a piece of. Apparently even Congress hasn’t been able to get these questions answered in a classified briefing.

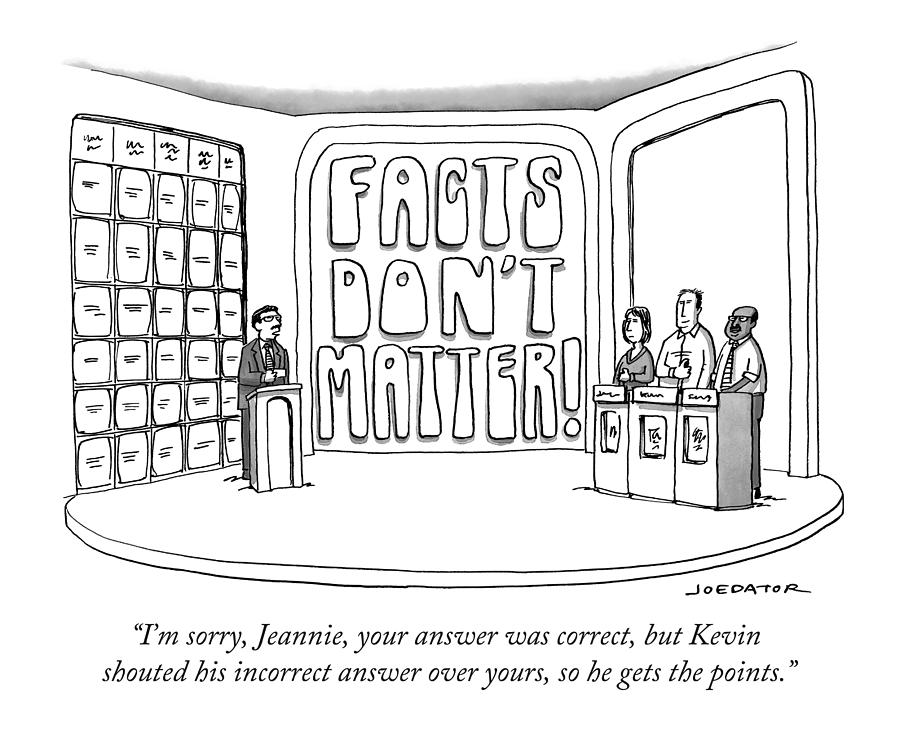

One of the ways Trump gets normalized is that we often compare his actions to his own previous conduct, as in “This is even worse than the last ridiculous thing he did.” As a result, our expectations of presidential behavior drift continually downward. I mean, sure, the claims of an “imminent” threat to American lives, some deadly Iranian scheme that came apart because we killed Soleimani, are almost certainly false. (Once a plot is under way, i.e., truly “imminent”, you disrupt it by stopping the perpetrators, not blowing up the mastermind. Killing Bin Laden after the hijackers were on their way to the airport would have done nothing to prevent 9/11.) But Trump’s like that — what’s one more lie after the many thousands we’ve already heard from him?

/https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thestar/opinion/editorial_cartoon/2020/01/07/theo-moudakis-lies-to-date/theo_moudakis_lies_to_date.jpg) Another way we normalize Trump is to cut his actions into tiny pieces and find horrifying precedents for each one. (As in: “So Trump lied about the imminent threat? W lied about WMDs.”) And so we allow the Trump administration to become a Frankenstein monster, stitched together from all the worst aspects of previous presidencies.

Another way we normalize Trump is to cut his actions into tiny pieces and find horrifying precedents for each one. (As in: “So Trump lied about the imminent threat? W lied about WMDs.”) And so we allow the Trump administration to become a Frankenstein monster, stitched together from all the worst aspects of previous presidencies.

To correct these normalizing tendencies, I want to raise the question: What do we normally expect from an American president when there’s been a major military development?

Talk to us. The very least we expect from a normal president is that he address the American people, to acknowledge what has happened himself, as soon as possible.

This tradition is as old as mass media. The day after the Pearl Harbor attack, President Franklin Roosevelt addressed a joint session of Congress, calling December 7 “a date that will live in infamy” and asking the House and Senate to declare war on Japan. The speech was broadcast live over the radio, and “attracted the largest audience in US radio history, with over 81% of American homes tuning in”.

[The speech] was intended not merely as a personal response by the President, but as a statement on behalf of the entire American people in the face of a great collective trauma. In proclaiming the indelibility of the attack, and expressing outrage at its “dastardly” nature, the speech worked to crystallize and channel the response of the nation into a collective response and resolve.

Every subsequent president has carried on this tradition of using the mass media to reach out to the American people when issues of war and peace arose. This week I examined a number of such examples, including these:

- In 1950, President Truman went on television to explain what was happening in Korea, and how the mobilization of American troops would (or would not) affect the American people. (“Hoarding food is especially foolish. There is plenty of food in this country.”)

- Within an hour of the signing of the Korean armistice, President Eisenhower gave a televised address.

- President Kennedy went on TV to announce the “quarantine” of Cuba during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

- President Johnson interrupted normal TV programming to tell the American people about the Gulf of Tonkin incident and his response to it.

- President Nixon made 14 televised addresses to the nation about Vietnam; including this one announcing the operation in Cambodia.

- Jimmy Carter spoke to the nation about the Iranian hostage crisis.

- Ronald Reagan addressed the country after the Marine barracks bombing in Beirut and our invasion of Grenada.

- George H. W. Bush announced that he was sending troops to Saudi Arabia in response to Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait, the first in a series of responses that ultimately included Operation Desert Storm.

- Bill Clinton announced airstrikes against Serbia.

- George W. Bush announced on October 7, 2001 that bombing had started in Afghanistan.

- Barack Obama announced on May 2, 2011 that Osama Bin Laden had been killed.

How a normal president sounds. I could have included many other examples, but the list above is a good sampling. Some the actions announced turned out well and some turned out badly. (It’s probably unfair to expect him to have foreseen this, but Nixon’s Cambodia campaign was a step down the road to the killing fields.) Some of the speeches were more honest than others. (The Gulf of Tonkin incident, for example, was not quite how LBJ described it.) But despite the differences in era and philosophy and personality, all these speeches share a number of features that made them “presidential”.

The most obvious thing they share is a tone: They are all calm but serious. The President, whoever he might have been at the time, projects an attitude of thoughtful determination, as if he were saying “I know there will be consequences to this act, but I have thought them out to the best of my ability. I am not acting rashly out of unreasoning fear or blind anger.”

They are also in some manner humble. This might seem like a strange trait for a leader to display when he is invoking the greatest power his office affords him, but American presidents do not hold their power as a personal possession, the way a divine-right king would. Presidential power is held in trust for the American people. No one is worthy of the power to start bombing some other country or to send troops into harm’s way, but our country has to place that power somewhere. So we have placed it in our president, under supervision from the Congress, who is just a human being like the rest of us. Any human who assumes that power is quite right to be awed by it.

The speeches are not self-aggrandizing, which is the opposite of humble. FDR, for example, could have used the opportunity to pat himself on the back: He had shown the foresight to begin a draft a little over a year before. His Lend-Lease program had armed countries that would now be our allies, and had developed a weapons industry we would now be relying on. But he mentioned none of that.

Unity. Every one of the speeches is an attempt to unify Americans behind the action being announced and the policy it represents. Consequently, they all strive to be non-partisan. Again, look at FDR: He could have reminded the country that Republican congressmen voted against Roosevelt’s Lend-Lease Act 24-135, a decision that now looked short-sighted. That might have scored points with the voters and helped Democrats unseat those Republicans. But he made no mention of parties: The nation had been attacked, and he called for the nation — not just his party — to respond.

That model has stood until the present administration. Frequently in the speeches above, the president quotes or refers to some past member of the other party to demonstrate the bipartisan nature of the policy he is carrying out. Ronald Reagan quoted former Democratic Speaker Sam Rayburn. Nixon referenced a bipartisan list of presidents:

In this room, Woodrow Wilson made the great decisions which led to victory in World War I. Franklin Roosevelt made the decisions which led to our victory in World War II. Dwight D. Eisenhower made decisions which ended the war in Korea and avoided war in the Middle East. John F. Kennedy, in his finest hour, made the great decision which removed Soviet nuclear missiles from Cuba and the western hemisphere.

Johnson’s speech is especially noteworthy in this regard, because it took place in August, 1964, just three months before the election. The idea that Barry Goldwater was a hothead not to be trusted with nuclear weapons would soon become a theme of Johnson’s reelection campaign, but nothing in the Gulf of Tonkin speech hints at that. Quite the opposite:

I have today met with the leaders of both parties in the Congress of the United States, and I have informed them that I shall immediately request the Congress to pass a resolution making it clear that our government is united in its determination to take all necessary measures in support of freedom and in defense of peace in Southeast Asia. I have been given encouraging assurance by these leaders of both parties that such a resolution will be promptly introduced, freely and expeditiously debated, and passed with overwhelming support. And just a few minutes ago, I was able to reach Senator Goldwater, and I am glad to say that he has expressed his support of the statement that I am making to you tonight.

In none of the speeches does the president snipe at his predecessors, blame them for the current predicament, or gloat over the way things have turned out. No president ever had a better opportunity to throw shade at the previous president than Barack Obama, who had succeeded at something George W. Bush had failed to do for seven years: kill Bin Laden. But Obama passed up that opportunity to boost himself by tearing down his predecessor. Instead, he acknowledged the “tireless and heroic work of our military and our counterterrorism professionals” over the previous ten years. He closed by asking Americans to

think back to the sense of unity that prevailed on 9/11. I know that it has, at times, frayed. Yet today’s achievement is a testament to the greatness of our country and the determination of the American people. … Let us remember that we can do these things not just because of wealth or power, but because of who we are: one nation, under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.

What is presidential? The presidential speeches seek to evoke three kinds of unity: Unity as Americans facing an external challenge, unity of vision between the president and Congress, and unity of the United States with its allies. The speeches are not always entirely truthful — among his other roles, the president is the country’s chief propagandist — but the untruths are aimed at the enemy, not at other Americans. The president takes a generous, hopeful view of how Congress, our allies, and the nation as a whole will respond. The vision is consistently about what we can do together, not what the president as an individual is doing for us or against our opposition. He seeks to paper over any past differences, in hopes of moving forward as a united nation.

Now look at Trump. The day after the Soleimani assassination, Trump made a public statement, but not a particularly formal one. He addressed reporters at Mar-a-Lago, not the nation from the White House. (The text begins “Hello everybody”, not “My fellow Americans”.) The brief announcement does not mention Congress or our allies, but has an unusual number of first-person references: “at my direction … under my leadership … I am ready and prepared to take whatever action is necessary”, leading up to Trump’s list of accomplishments:

Under my leadership, we have destroyed the ISIS territorial caliphate, and recently, American Special Operations Forces killed the terrorist leader known as al-Baghdadi. The world is a safer place without these monsters.

Trump also took a slap at previous administrations:

What the United States did yesterday should have been done long ago. A lot of lives would have been saved.

The message asks for nothing — not from the public, not from Congress, not from our allies. Trump simply reports what he has done for reasons that are not entirely clear. (It can’t be that we have a right to know.) He does not warn us of hardships to come, or of possible Iranian reprisals. He warns Iran, though of what “I” will do.

The United States has the best military by far, anywhere in the world. We have best intelligence in the world. If Americans anywhere are threatened, we have all of those targets already fully identified, and I am ready and prepared to take whatever action is necessary. And that, in particular, refers to Iran.

After Iran’s response — a missile attack on the Iraqi base from which the Soleimani mission was launched — Trump finally gave a more formal speech from the White House. He begins, not with a salutation to the audience or even with a statement of the policy of the United States, but with a pledge from Trump the Individual:

As long as I am President of the United States, Iran will never be allowed to have a nuclear weapon.

He does not say how he will prevent that from happening, given that he tore up the agreement that had been blocking Iran’s nuclear program. He goes on to ramble fairly incoherently about the evils of Iran. Again he does not mention Congress, and while he does mention both NATO and the partner countries in the Iran nuclear deal, it is not at all clear what he wants them to do, other than “recognize reality”.

Again, he exaggerates his “accompliments”:

Over the last three years, under my leadership, our economy is stronger than ever before and America has achieved energy independence. These historic

accompliments[accomplishments] changed our strategic priorities. These are accomplishments that nobody thought were possible. And options in the Middle East became available. We are now the number-one producer of oil and natural gas anywhere in the world. We are independent, and we do not need Middle East oil.The American military has been completely rebuilt under my administration, at a cost of $2.5 trillion. … Three months ago, after destroying 100 percent of ISIS and its territorial caliphate, we killed the savage leader of ISIS, al-Baghdadi. … Tens of thousands of ISIS fighters have been killed or captured during my administration.

But the most unpresidential thing of all in this speech is the way that he goes after his predecessor, in some cases distorting the truth to do so, and in other cases just simply lying. Under Obama’s Iran deal, “they were given $150 billion”. [False. A much smaller sum of Iran’s own money was unfrozen. Iran was “given” nothing.] “The missiles fired last night at us and our allies were paid for with the funds made available by the last administration.” [Theoretically possible, but Trump provides no evidence. He appears to have just made this up.] “The very defective JCPOA expires shortly anyway, and gives Iran a clear and quick path to nuclear breakout.” I’ll let PolitiFact handle that one:

This is False.

The Iran deal put a cap on enriched uranium that would have lasted until 2030, at which point other agreements would have continued to limit Iran’s nuclear development.

Some of the deal’s restrictions would have eased beginning in 2025, but the key elements that prevented Iran from enriching the levels of uranium needed to make a bomb would have remained in effect until 2030.

Other terms would have lasted forever, including the prohibition on manufacturing a nuclear weapon and a provision requiring compliance with oversight from international inspectors.

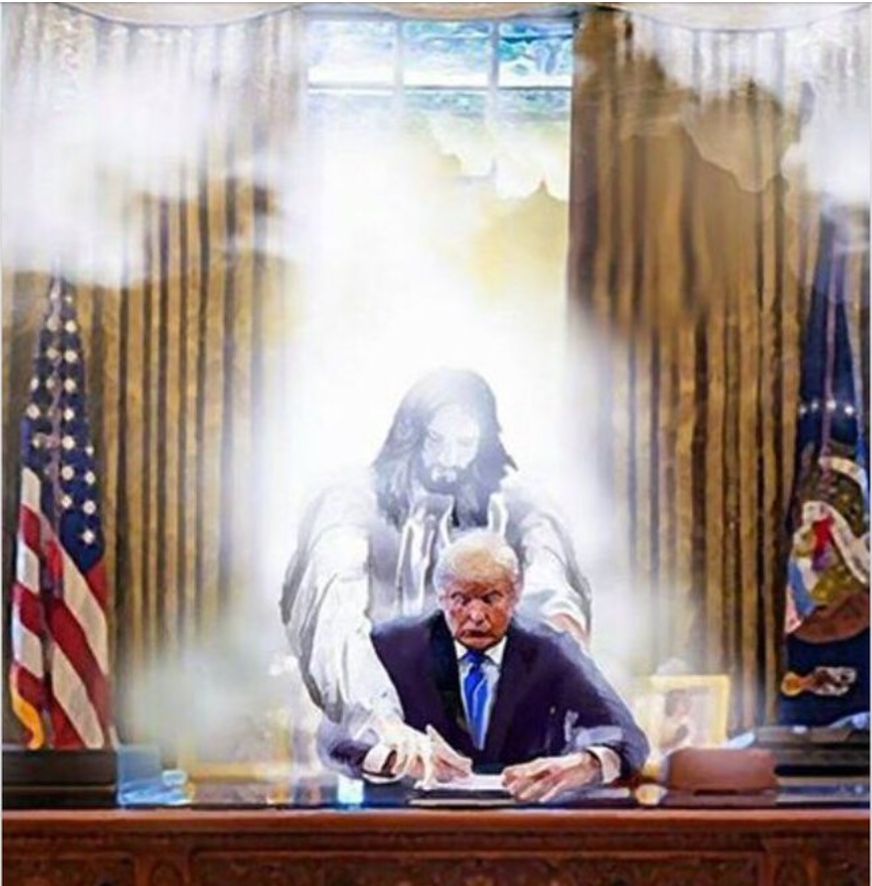

Think about what these statements do, relative to what we would expect from any previous president. They feed a cult of personality around Trump. He is not the current avatar of the President of the United States, he is himself, accomplishing things that his predecessors at best played no role in, and more often provided obstacles he had to overcome. He wields power as a personal possession, not in trust from the American people or overseen by Congress. America’s allies are not equals, they are vassal states that he need not consult, but can make demands on.

He makes no appeal for unity, and does not reach out to the opposition party. Instead, he uses the attention provided by the current crisis to claim his predecessor’s accomplishments (we became the top oil producer under Obama), and to spread lies about him. Democrats should feel slapped in the face by this, not invited into an American unity.

In addition to the televised addresses, Trump has access to media FDR never imagined. His Twitter feed has been non-stop partisan, in the most vicious way. Just this morning, for example, he retweeted an image of Chuck Schumer and Nancy Pelosi in Muslim dress, with an Iranian flag behind them. In his own words, he told this lie:

The Democrats and the Fake News are trying to make terrorist Soleimani into a wonderful guy

Nothing he says speaks to Democrats in Congress, or to the 54% of the American people who voted for someone else in 2016, or the 53.4% who voted for Democratic candidates for Congress in 2018. He is leading us down a path that may well end up in war, without seeking approval from Congress or even trying to make a case to anyone other than the minority of the country that supports him.

No previous president would do such a thing.