a tentative start to a historical investigation

Last week I argued that mere election tactics — a more attractive candidate, some new slogans, a better framing of the issues — will not be enough to overcome the MAGA movement in the long run. (We defeated them soundly in the elections of 2018 and 2020, but MAGA showed amazing resilience.) MAGA itself is not just an unfortunate convergence of political forces, it is a cultural movement of some depth. Defeating it will require a counter-movement.

The 2024 campaign showed that the counter-movement can’t just be a reversion to some prior status quo. My assessment of how the Harris campaign failed is that Trump managed to tag Harris as the candidate of the status quo and present himself as the candidate who will shake things up. [1]

Harris’ problem was that (as a whole) the status quo is not working for many Americans. I listed a number of ways that things are not working, but fundamentally they boil down to this: It gets harder and harder to plan for a successful life with any confidence that your plan will succeed. Far too many Americans feel that the system is stacked against them, and that simply trying harder is not the answer.

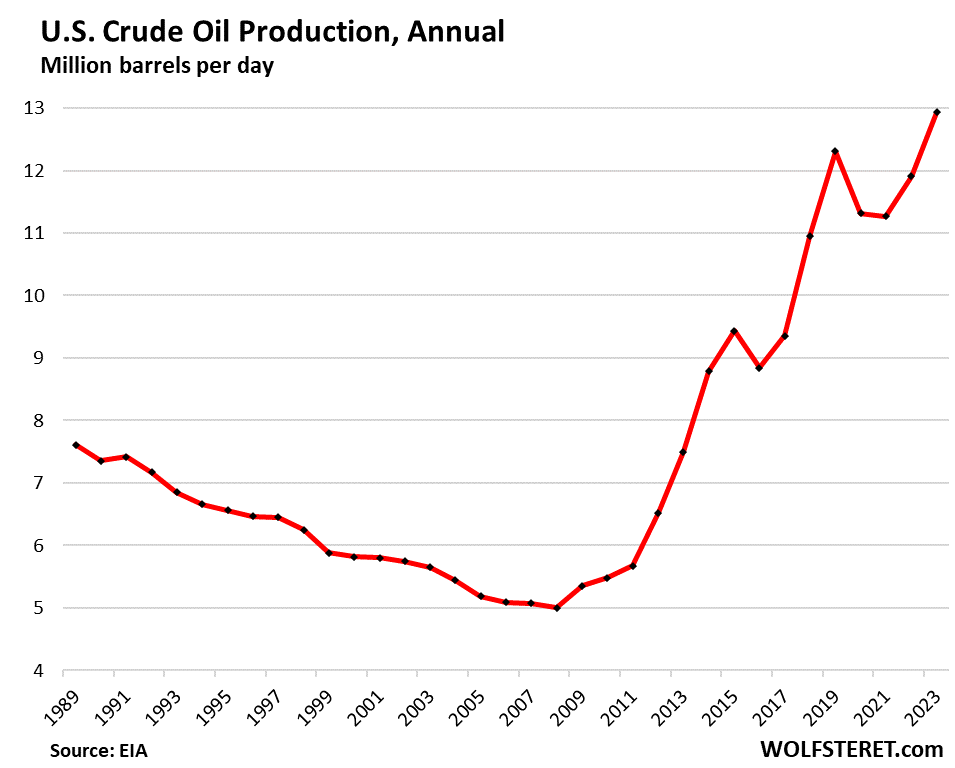

Rather than present any coherent program, Trump has responded to the public’s justified anxiety with scapegoating and nostalgia: Immigrants, foreigners, minorities, and people who rebel against their assigned gender roles are the problem, and we should look to the greatness of America’s past — now, apparently, the high tariffs of the 1890s — for our salvation. To the extent that he has a plan — like ignoring climate change and reverting to the fossil-fuel economy of the 20th century — it is likely to be counterproductive.

But “don’t do that” has turned out to be an unpersuasive message for the Democrats. It worked when Trump was in office, actively doing unpopular things. But as soon as he was defeated, nostalgia renewed its charms. To a large extent, Trump’s 2024 message was that electing him would make it 2019 again, and all the disruption of the Covid pandemic (including the parts he brought on himself) would be behind us.

But realizing that we need a deeper movement is not the same as having one, or even knowing what it would be or how it might come together.

With that question in mind, I’ve been looking at history. Despite recently being idealized as the new “again” in Make America Great Again, the late 1800s were a low point in American history, dominated by the robber barons of the Gilded Age. Industry after industry was reorganizing as a monopolistic trust with the power to maximally exploit both workers and consumers. It was a hard time both for urban factory workers and rural small farmers.

Somehow, things got better: Antitrust laws got passed. Governments began to regulate working conditions, product safety, and child labor. Standard Oil was broken up. Unions began to win a few battles. And the gap between rich and poor narrowed. The New Deal was unthinkable in 1880, but by the 1930s it was popular. This was a profound change in what David Graeber referred to as “political common sense“. How did it happen?

A friend recommended a place to start: The Populist Moment by Lawrence Goodwyn. The book was published in 1978, so to the extent that it says something about the present day, either about MAGA or how a democratic movement might oppose it, that message arises naturally from the history, and not from some pro- or anti-Trump bias of the author. [2]

What was Populism? These days, MAGA and similar neo-fascist movements in other countries are often described as “populist”, but the version in the late 1800s was quite different. There is a surface similarity — in each case, large numbers of working class people found themselves resisting their era’s educated consensus — but from there things diverge fairly quickly.

In the 19th century, farming was still the largest American occupation, employing over half the labor force as late as 1880. But the system was stacked against small farmers in two ways: First, farmers with no capital beyond their land found themselves at the mercy of “furnishing merchants”, who would lend money for them to plant a crop (and survive through the growing season) in exchange for a contract on the harvest. Once he had contracted with a furnishing merchant, the farmer was stuck with that merchant, and would typically end up both paying high prices for his supplies and receiving a low price for his crop. [3]

But second, that long-term situation was made much worse by post-Civil-War monetary policy. The Civil War had been financed in part by printing paper currency, known as “greenbacks“. That had caused inflation during the war, and the prevailing economic wisdom of the time was that the dollar needed to be made “sound” again. In other words, the greenbacks had to be withdrawn from circulation, so that all US money could be redeemable for gold again. (Greenbacks became fully convertible to gold in 1878.)

In modern terms, the government’s policy was to shrink the money supply. If expanding the money supply had caused inflation, shrinking it could be counted on to achieve deflation; i.e., prices would come back down.

if you think like a consumer, deflation sound great. (Just last fall, that’s what Trump was promising his voters: “Prices will come down. You just watch: They’ll come down, and they’ll come down fast.”) But now imagine being a farmer who is counting on selling his wheat or cotton at the end of the season: You bought and borrowed when prices were high, and now you have to sell when prices are lower. The result was that large numbers of farmers were failing to clear their debts. Every year, many would lose their land and wind up as sharecroppers or worse.

The conventional wisdom of the time was that, sure, times were hard. But the “sound dollar” had to be restored, so farmers would just have to become more efficient. If some had to go broke in the process, well, that’s capitalism for you. Creative destruction and all that.

At some point, though, farmers began to realize that this wasn’t a story of individual failure, but of a badly structured system. And some postulated a solution: Farmers could cooperate rather than compete. They could form “farmer alliances” to pool their resources, negotiate for common supplies, and market their crops collectively.

Through the 1870s and 1880s, farmer alliances played a game of escalating pressure with the merchants and banks. Initial co-op successes would lead to new merchant strategies to freeze the co-ops out of the market, resulting in some larger co-op plan. The ultimate trump card was played by the system’s last line of defense, the bankers: Banks would take mortgages on individual farms (the old model), but they would loan nothing to a co-op backed by the land of its members.

Watching the more prosperous classes act in concert to thwart their plans radicalized the farmers and made them turn to politics. They created the People’s Party, whose presidential candidate carried four western states in the 1892 election. The party was organized around a platform, some of which was achieved decades later, but much of which might still be considered radical today. It wanted a revision of the banking system that would orient it toward the interests of “the producing classes” rather than “the money trust”. It wanted a flexible money supply (which we have today) rather than a gold standard. And it wanted government ownership of the railroads and other essential utilities that could be manipulated against working people by monopolies and trusts.

Ultimately, the People’s Party supported the Democratic candidate, William Jennings Bryan, in 1896, and then faded into insignificance.

So Populism was a failure in the sense that it never achieved power. But David Graeber once said that “one of the chief aims of revolutionary activity is to transform political common sense”. By that standard, Populism was more successful. [4]

Partisanship. The People’s Party ran into partisan loyalties that were left over from the Civil War and generally had more to do with identity than with life experience. If you were a White Southern Protestant or a Northern urban Catholic, then you were a Democrat. But if you were a Northern Protestant or a Southern Negro, you were Republican. Those loyalties were hard to break, and each party charged that the Populists were really agents of the other party. “Patriotism” meant faithfulness to the team your people played on during the War.

How movements happen. Goodwyn has a lot to say about this, and argues against the view that protest movements arise naturally during “hard times”. History, he says, does not support this.

“The masses” do not rebel in instinctive response to hard times and exploitation because they have been culturally organized by their societies not to rebel. They have, instead, been instructed in deference.

He points to parallel ways this worked in his own day on both sides of the Iron Curtain. (This is 1978, remember.)

The retreat of the Russian populace represents a simple acknowledgment of ruthless state power. Deference is an essential ingredient of personal survival. In America, on the other hand, mass resignation represents a public manifestation of a private loss, a decline in what people think they have a political right to aspire to — in essence, a decline of individual political self-respect on the part of millions of people.

He then asks the billion-dollar question:

How does mass protest happen at all then?

Which he then proceeds to answer: There are four stages:

- forming: the creation of an autonomous institution where new interpretations can materialize that run counter to those of prevailing authority

- recruiting: the creation of a tactical means to attract masses of people

- educating: the achievement of a heretofore culturally unsanctioned level of social analysis

- politicizing: the creation of an institutional means whereby the new ideas, shared now by the rank and file of the mass movement, can be expressed in an autonomous political way.

And he notes that “Imposing cultural roadblocks stand in the way of a democratic movement at every stage of this sequential project.”

For the populist movement, the first stage was the creation of farmers’ alliances. After years of experimenting, the farmers alliances came up with a mass recruitment model: large-scale cooperatives that farmers could join in hopes of getting cheaper supplies, better crop prices, and various other benefits. Then the co-ops themselves became educating institutions that taught farmers how the monetary system tilted the playing field against them, and how an alternative system might work. And finally the People’s Party itself provided an electoral outlet.

How well the People’s Party did in various states corresponded to how well the previous stages had taken hold.

In the 20th century, labor unions played a similar role to the co-ops: Masses of workers would join a union in hope of getting better pay and improved working conditions. And the union would then educate them in the issues relevant to their situation. [5]

MAGA. It’s worth considering how Goodwyn’s model applies to MAGA. You wouldn’t expect it to fit perfectly, because fundamentally MAGA isn’t a democratic movement. There has always been big money behind it, and the grassroots aspects, while genuine in some sense, also include quite a bit of astroturf. [6]

However, there are a number of parallels. The initial hurdle MAGA faced was getting its working-class foot-soldiers to believe in themselves rather than be intimidated by experts like economists, climate scientists, and medical researchers. The internet has undoubtedly made this easier, but the validation of “doing your own research” was also key.

And what was the recruiting institution that could attract masses of people and educate them in the new way of looking at the world? Evangelical churches. People came to them for the variety of reasons that always attract people to churches, and usually not for political indoctrination. But once there, they could be taught that elite scientists (like those promoting anti-Genesis ideas of evolution) were agents of the Devil. Their sense of grievance could be raised and sharpened, and the whole idea of a fact-based or reason-based worldview could be undermined. You might join because you enjoyed singing in the choir, but after a few years you were ready to believe that DEI was an anti-White conspiracy, or that economic malaise was God’s punishment for tolerating gay marriage and trans rights. You were ready to march for Trump.

Counter-movement. The lack of an obvious recruiting-and-educating institution is an obvious hole in the formation of an anti-MAGA counter-movement. Conservatives seem well aware of possible avenues — like the universities, a revitalized union movement, or even charitable activities like refugee resettlement or soup kitchens — and are committed to shutting them down.

Conversely, this is why a number of left-leaning voices (Perry Bacon, for one) are encouraging their listeners to connect with institutions where they can meet with like-minded folks.

I find the historical pattern evocative, even if I can’t immediately see how to implement it: The recruiting-and-educating institutions offer a very simple practical advantage: higher wages, say, or better crop prices. But by engaging in the institution’s core activity, people begin to see the oppressive forces arrayed against them, and begin to radicalize.

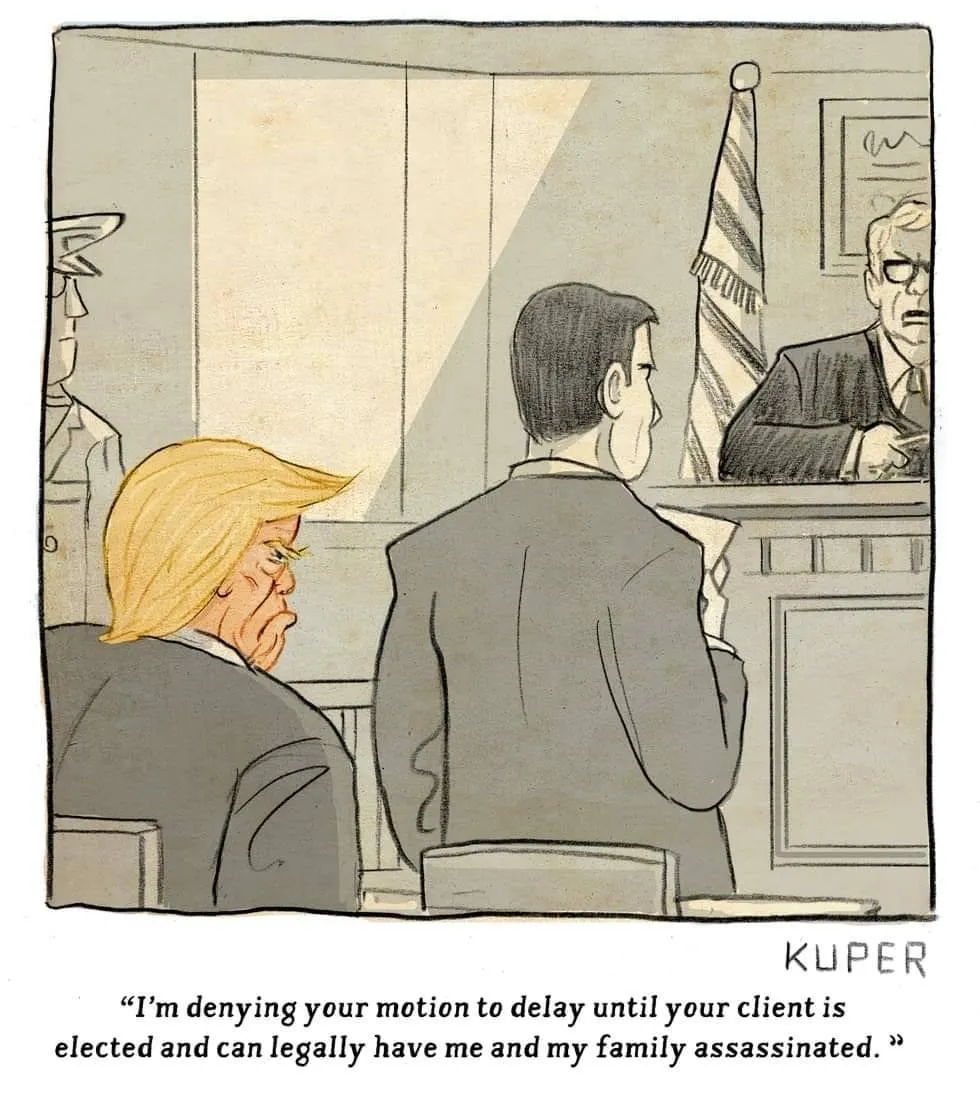

[1] And indeed, he is shaking things up. In my opinion, however, the parts of the status quo he is attacking are the best parts: the rule of law, the separation of powers, and the independence of federal institutions like the Department of Justice and the military, just to name a few.

Trump’s attacks on what he calls “the Deep State” are telling. If you know any federal employees, you probably understand that there is a Deep State, but it’s not the monster Trump paints it as.

The Deep State consists of federal workers who are more committed to the mission of their agencies than they are to the current administration. So career EPA officials will resist a president who wants to harm the environment, career prosecutors will drag their feet about harassing the current administration’s political enemies, career public health officials will do their best to support best practices against pressure from above, and so on. To the extent that the agencies are well set up and well motivated, their employees’ loyalty to the agency mission is a good thing, not a bad thing.

[2] Populism is literally just a place to start. I’m going to be delving into other aspects of the 1870-1941 period in future posts.

[3] Something similar happened to miners and factory workers who were paid in vouchers that could only be redeemed at company-approved merchants, who used that monopoly power to drive workers ever deeper into debt. As 16 tons puts it “I owe my soul to the company store.”

[4] Another movement that benefits from Graeber’s political-common-sense standard is the French Revolution. It is frequently judged a failure (especially by comparison to the American Revolution) because it didn’t achieve a lasting Republic, but instead devolved into the Reign of Terror and the dictatorship of Napoleon. However, the French Revolution changed political history. Before the revolution, absolute monarchy was still seen as a valid and plausible form of government. Afterwards, it wasn’t. The Czars of Russia might hang on for another century or so, but the writing was on the wall.

[5] It is unfortunate that farmers alliances and labor unions didn’t peak at the same time. Combined, they might have achieved significant political power.

[6] MAGA precursors, like the John Birch Society and the Tea Party, always had wealthy donors. You can see the pattern in present-day groups like Moms for Liberty. While there are indeed concerned moms in Moms For Liberty, the group’s expansion has been greased by professional consulting and seed money from wealthy establishment groups like the Heritage Foundation.