Most administrations come and go

without credible evidence of a crime by a cabinet official.

There were two this week alone.

In January of 2017, as Barack Obama was getting ready to hand the presidency over to Donald Trump after eight years in office, the Heritage Foundation’s Hans von Spakovsky pushed back on the “myth” that Obama had presided over a “scandal-free administration”. Von Spakovsky listed six of what he described as “some of the worst scandals of any president in recent decades”.

One — using the IRS to “target political opponents” — was nothing more than a canard that circulated inside the conservative information bubble. (The IRS was skeptical of the tax-exempt status of new political organizations founded to take advantage of the Supreme Court’s Citizens United ruling. Most of the investigated organizations were conservative, but that was due to the flow of money rather than specific targeting of conservative organizations. In the end, nearly all of them were recognized as tax-exempt. More importantly: No link back to the White House was ever established.)

Others — Benghazi, government personnel records getting hacked, losing track of guns allowed into Mexico as part of a smuggling investigation, veterans dying while waiting for appointments at the VA — were screw-ups not rooted in any nefarious intentions.

Only one — the Hillary Clinton email controversy — involved any credible accusation of a crime. That was investigated by the State Department during the first Trump administration, and the report found “no persuasive evidence of systemic, deliberate mishandling of classified information.” No one was ever charged with a crime, much less convicted.

That’s not unusual. Crime in the cabinet is exceedingly rare. In the history of the United States, no cabinet official was convicted of a crime until 1929, when former Interior Secretary Albert Fall was found guilty of taking bribes in the Teapot Dome scandal. Three Nixon cabinet members and his vice president were convicted of crimes, which is one reason why the Nixon administration is remembered for its corruption.

But the Trump administration has a way of wearing down our standards and making us forget that lawlessness high in the executive branch used to be exceptional. For example, Trump officials violate the Hatch Act (banning government officials from using their offices for political activity) just about every day. Such violations went unpunished in the first Trump administration, so hardly anyone notices any more.

Even so, it was striking to hear two independent credible accusations of crimes by Trump cabinet officials in the same week.

- DHS Secretary Kristi Noem all but confessed to contempt of court yesterday when she admitted she knew a federal judge had ordered a plane carrying detainees to El Salvador to turn around, but she ordered it to continue.

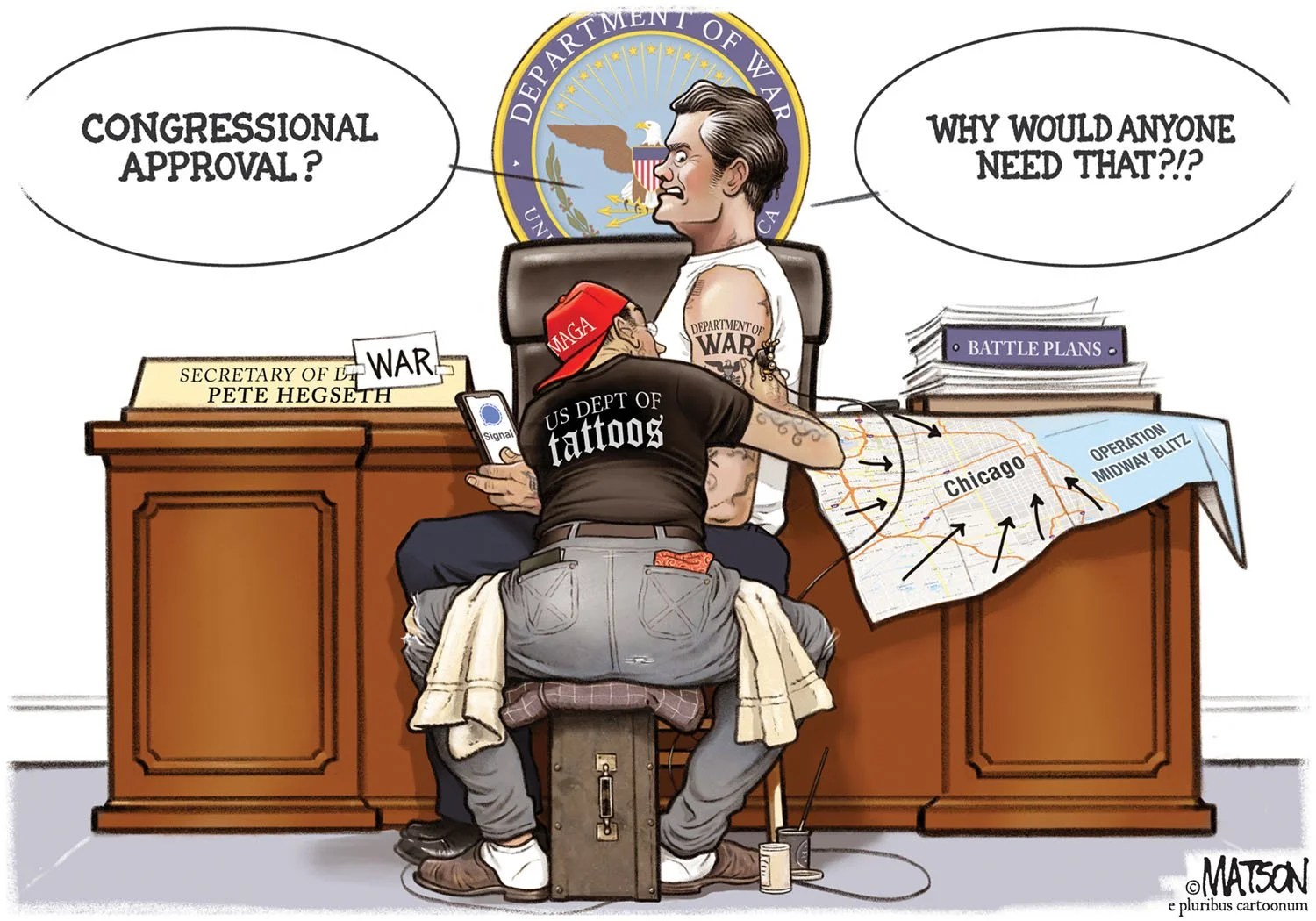

- Department of

WarDefense Secretary Pete Hegseth reportedly gave an order to “kill everybody” in an attack on an alleged drug-smuggling boat in the Caribbean. Two survivors clinging to wreckage were then killed in a second attack. Even if the initial attack were legitimate (which it wasn’t), killing defenseless survivors is a war crime.

The second crime is more serious than the first, so let’s start there.

“Kill everybody”. Since September 2, the Trump regime has launched at least 21 attacks against boats on the high seas that it claimed were smuggling drugs, killing at least 83 people. Friday, that story got even worse, when the Washington Post published a report that Defense Secretary Hegseth had given a “kill everybody” order for the first attack. Two people survived the initial attack and were clinging to the wreckage when a second attack was ordered. It blew the survivors to bits.

If true, that incident is a clear war crime attributed to a specific person, Hegseth.

Horrifying as that is, I think it would be a mistake to lose sight of the larger picture: If we frame this wrong, it might seem as if the air campaign against the boats was fine until helpless survivors were targeted. It wasn’t. Whether Hegseth ever said “Kill everybody” or not, under his command the Department of Defense has committed 83 murders.

No operational consideration justifies the attacks. They are not like the drone attacks that have assassinated terrorist leaders, controversial and morally dubious as those might have been. In those cases, the targets might not have stayed in known locations long enough for a strike team to get there. Or the host country might not have allowed our strike team in. Often, the choice was either to send a drone or let the terrorists go on about their business.

That’s not the case here. These boats were in open seas dominated by our Navy. They could have been seized and could not have gotten away. Whatever drugs they might have been carrying would never have reached American consumers. The crews could have been captured alive, and might have given us valuable information about their suppliers or distributors.

So attacking the boats achieved nothing that couldn’t have been achieved without killing people. Instead, the Trump regime chose to kill 83 people.

Remember: Smuggling drugs is not a capital crime. Even if the alleged smugglers had been captured and given due process, they could not have legally been sentenced to death.

It’s worthwhile to put this in a more familiar context. In Clint Eastwood’s Dirty Harry movies, Harry Callahan is a cop who chafes under the legal restrictions that bind him, and that allow criminals to eventually go free. In the first movie, Harry dares a suspect to go for a gun so that he can legally kill him.

But the second movie, Magnum Force, pits Harry against a death squad of rogue cops who start a campaign of assassinations against the city’s underworld kingpins. The squad expects Harry to join them, but rogue assassinations are too much even for him. “A man’s got to know his limitations,” Harry says.

That’s what we’re seeing now: Trump and Hegseth have turned the US Navy into a rogue assassination squad. They see enough evidence to convince themselves boats are smuggling drugs, show that evidence to no one, and kill the alleged smugglers on their own authority.

Even if you’re as tough on crime as Dirty Harry, you shouldn’t approve. A government has got to know its limitations.

The Trump regime gives two justifications: First, the end justifies the means (which is precisely what Dirty Harry’s rogue cops argued). On October 23rd, Trump made the ridiculous claim that each boat blown up saves the lives of 25,000 Americans. (This is the same kind of math that caused Pam Bondi to claim that drug seizures during Trump’s first 100 days had saved 119-258 million lives.) He postulated that if he told the Congress about the operation (not to seek their authorization, which he says he doesn’t need) “I can’t imagine they’d have any problem with it. … What are they going to do, say ‘We don’t want to stop drugs pouring in’?”

Again, those boats could be stopped without blowing them up or killing anybody.

Second, the regime stretches the definition of “war” to cover this operation. The drug cartels, say Hegseth and Trump, are like ISIS or Al Qaeda. This is typical of the way the regime perverts language, so that reminding soldiers of their legal responsibility not to follow unlawful orders is “sedition”, or individuals deciding to cross our border is an “invasion”.

Smuggling has been part of the American economy since before the Revolution, from British tea to Prohibition whiskey to Colombian cocaine. It has never been considered an act of war. Those 83 people on those fishing boats were not soldiers and were not at war with the United States. They’re murder victims.

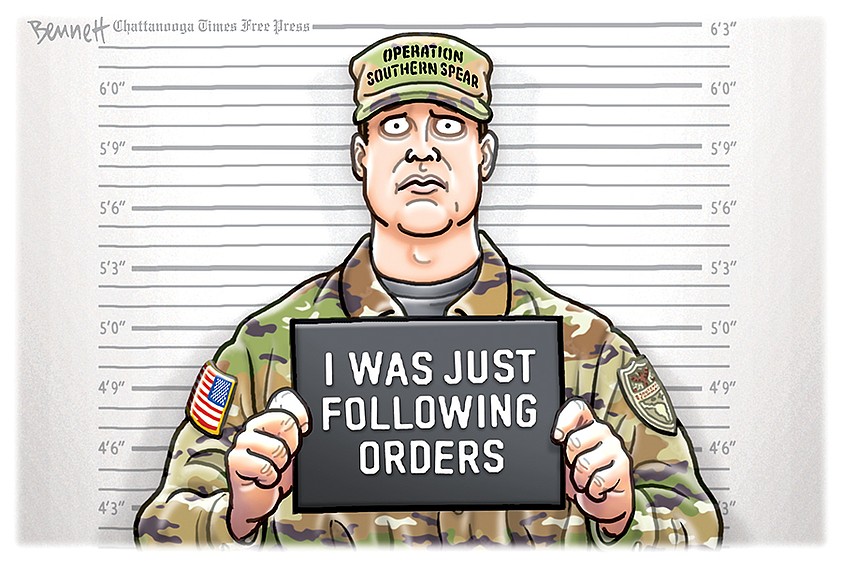

But just for a moment, grant the claim that these attacks are part of a war. That’s where the Post’s new revelations come in: Once your enemies are disarmed and helpless, it’s a war crime to kill them. If the report is true, Pete Hegseth and those down the chain who carried out his orders are guilty of war crimes.

It appears, at least for the moment, that Republicans in Congress are not going to cover this up.

Republican Sen. Roger Wicker of Mississippi, chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, and its top Democrat, Rhode Island Sen. Jack Reed, said in a joint statement late Friday that the committee “will be conducting vigorous oversight to determine the facts related to these circumstances.”

That was followed Saturday with the chairman of the House Armed Services Committee, Republican Rep. Mike Rogers of Alabama, and the ranking Democratic member, Washington Rep. Adam Smith, issuing a joint statement saying the panel was committed to “providing rigorous oversight of the Department of Defense’s military operations in the Caribbean.”

Hegseth denies giving the order and calls the Post’s report “fake news”.

And before I leave this topic, there is one more dot worth connecting: Military judge advocate generals (JAGs) are supposed to vet these legal issues for the armed forces. But Hegseth purged the JAGs back in February, about a month into his term:

Hegseth told reporters Monday that the removals were necessary because he didn’t want [the JAGs] to pose any “roadblocks to orders that are given by a commander in chief.”

The plan from the beginning was to give illegal orders and remove all obstacles to carrying them out.

Kristi Noem’s contempt of court. Remember back in March, when a judge ordered DHS not to deport a bunch of Venezuelans to the CECOT concentration camp in El Salvador, including turning around planes already in the air? And DHS in fact did not turn those planes around, defying the judge’s order?

The judge, James Boasberg, has kept pursuing the question of who is responsible and whether they should be charged with criminal contempt of court. Tuesday, government lawyers answered the first question: DHS Secretary Kristi Noem made the call, after consulting with Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche, Principal Associate Deputy Attorney General (now federal appellate judge) Emil Bove, and DHS acting general counsel Joseph Mazzara.

Dean Blundell cuts through the spin and legalese to draw this conclusion: The regime just threw Noem under the bus. Government lawyers say they’ll be happy to answer any further questions in writing, but that “No live testimony is warranted at this time.” In other words: We’ll answer the questions we want to answer with very carefully crafted spin, and we don’t want to give the court or anybody else the ability to frame their own questions or insist on clear answers.

Blundell summarizes:

- They’re naming Noem now.

- They’re trying to keep her off the stand.

- And they’re trying to keep other insiders and whistleblowers from testifying live

Noem responded yesterday in an interview with ABC’s Jonathan Karl:

KARL: So, I have two questions on that. First of all, is that right? Does the — does the buck effectively stop with you on this? Was this your responsibility? And had you known the judge had ordered those planes to be turned around when that order was issued?

NOEM: Yes, I made that decision. And that decision was under my complete authority and following the law and the Constitution and the leadership of this president, who is dedicated to getting dangerous criminal terrorists and gangs and cartels out of our country. And I’m so grateful that we get the opportunity every day to do that and to make decisions that will keep America safe.

KARL: Did you know about — did you know about the judge’s order when you issued your order for the planes to go (ph)?

NOEM: You know, this is an activist judge. And I understand, you know, we’re still in litigation with this against this activist judge who’s continuously tried to stop us from protecting the American people.

We continue to win. His ridiculous claims are not in good standing with the law or the Constitution. We’ll win this one as well. And we comply with all federal orders that are lawful and binding and we will continue to do that.

But I’m proud of the decision that I’ve made. Proud to work for this president each and every day to keep America safe.

So there you have it: It’s up to the regime, and not the courts, to decide what is “lawful and binding”. She disagreed with the judge, so she ignored his order. If that’s not contempt of court, I don’t know what is.