This week’s eulogies told us more about the hero we need

than the man we’ve lost.

In the classic John Ford western The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, a senator from an unnamed western state (Ranse Stoddard, played by Jimmy Stewart) is a living legend, and the legend goes like this: Once an idealistic young lawyer from the East, he arrived in the West to discover a town being terrorized by the gunslinger and gangster Liberty Valance. Though he barely knew how to shoot, Stoddard’s refusal to run away landed him in a gunfight with Valance, which he somehow won. Then Valance was dead and his tyranny ended.

Stoddard himself was ashamed to have killed a man in a lawless gunfight, but ever after, he was the Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. On the strength of that reputation, he was chosen for the statehood convention, and then to represent the territory in Washington. When the territory became a state, he served three terms as its first governor, and then went on to the Senate. Now a national figure and a senior statesman, he is in line to be the next vice president.

But the truth about Stoddard is a bit more complicated: He did face Valance, got a shot off, and Valance wound up dead — but not because Stoddard’s shot killed him. Though he never promoted himself as Valance’s killer, he was never in a position to deny it either. So the story grew up around Stoddard and stuck with him because it was the myth that the West needed to tell: The Lawyer had killed the Gunslinger; the rule of law had ended the reign of violence.

Now Stoddard is finally able to tell the true story, because the man who did kill Valance is dead and can’t be tried for murder. But after he is done telling it, the local editor tears up his reporter’s notes and burns them. “This is the West, sir,” he explains. “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

This week we celebrated the memory of another legendary western senator, John McCain. And we did it in pretty much the same way: We told the legend of the hero we need. That legend intersects with John McCain’s actual life in a number of ways, but the story of the real man is much more complicated — and in many ways less relevant to those of us who didn’t know him.

So by all means, let us discuss the legend, because it tells us a great deal about the times we live in.

The Trump Era. No president in my lifetime (or maybe ever) has dominated the national conversation the way Donald Trump does. Whether you love him or hate him, whether he fills you with pride or disgust, it’s hard to talk about anything or anybody else for very long.

The Trump style is made up of bombast, rudeness, and above all, divisiveness. Unlike previous presidents, he does not reach out to those who voted against him. [1] When he speaks, he does not talk to the nation, he talks to his base. He lies constantly, and his personal life is a parade of sleaze. [2] Every issue, first and foremost, is about him.

Trump’s story is full of irony. Having run on a pledge to “Make America Great Again”, his character is defined by smallness. There is nothing magnanimous about him, and there seems to be no situation that he is able to rise above. He cannot laugh at himself, and rarely laughs at all. Every personal slight must be answered, every blow returned with double force. Gold Star parents, bereaved widows of soldiers, leaders of our closest allies — it doesn’t matter. No one must be allowed to cast a shadow on Trump’s fragile ego.

Having taken offense at every perceived disrespect for the symbols of America — the flag, the anthem, the police — his own loyalty to the nation is questionable; when the Russians attacked our system of government, his weak and subservient response added to the speculation that he is in league with them. Having pledged to “drain the swamp”, he has flaunted his conflicts of interest and presided over the most corrupt administration in many decades. Having won on the strength of the Evangelical vote, he has governed as the anti-Jesus [3], concentrating his cruelty on “the least of these” and favoring the rich man over Lazarus. Famous for saying “You’re fired!”, he actually has no stomach for face-to-face confrontations, preferring to let John Kelly do the dirty work, or to tweet something nasty after he has left the meeting.

Having taken offense at every perceived disrespect for the symbols of America — the flag, the anthem, the police — his own loyalty to the nation is questionable; when the Russians attacked our system of government, his weak and subservient response added to the speculation that he is in league with them. Having pledged to “drain the swamp”, he has flaunted his conflicts of interest and presided over the most corrupt administration in many decades. Having won on the strength of the Evangelical vote, he has governed as the anti-Jesus [3], concentrating his cruelty on “the least of these” and favoring the rich man over Lazarus. Famous for saying “You’re fired!”, he actually has no stomach for face-to-face confrontations, preferring to let John Kelly do the dirty work, or to tweet something nasty after he has left the meeting.

The hero we long for. What kind of hero do we need to celebrate in the Trump Era? One who embodies all the virtues that Trump so conspicuously lacks:

- higher purpose

- humility

- willingness to endure hardship

- courage

- magnanimity

- sense of humor

- devotion to principle

- idealistic vision of what America means and stands for

- respect for opponents and willingness to ally with them on issues of common concern

- compassion

- honesty even when the truth is not flattering

- willingness to confront facts and admit mistakes

It also wouldn’t hurt if that hero had a history of criticizing Russia. And it would be even better if he or she were a Republican, because a principled, virtuous, reasonable Republican Party is the single most conspicuous lack in America today. As a Democrat, I may yearn for a hero who can send the GOP into a long and well-deserved exile from power. But even better, I have to admit, would be to return to an America where the need to win was not so desperate, because Eisenhower-like Republicans could be trusted to preserve the Republic until we had a chance to make our case to the voters again.

McCain the legend. Was John McCain that hero? Sometimes. If we pick and choose properly, his life can bear the story we need to tell about it. [4]

He certainly endured hardship at the Hanoi Hilton, and in his final battle with cancer he showed that his fighter-pilot courage had not left him. President Obama said:

He had been to hell and back and yet somehow never lost his energy or his optimism or his zest for life. So cancer did not scare him.

Every time I heard him speak, at some point or other he stressed the importance of having a purpose higher than self. And it was there again (along with an idealistic vision of America) in his final message to the American people:

To be connected to America’s causes — liberty, equal justice, respect for the dignity of all people — brings happiness more sublime than life’s fleeting pleasures. Our identities and sense of worth are not circumscribed but enlarged by serving good causes bigger than ourselves.

McCain didn’t say it explicitly, but it’s clear that he didn’t envy the guy who lives in a golden penthouse and has sex with porn stars (who he then needs to pay off). “I have often observed that I am the luckiest person on earth,” he wrote.

Humility, sense of humor … I first saw McCain in 1999, when he was running against George W. Bush in the New Hampshire Republican presidential primary. I wasn’t blogging then, so I have no record of what he said beyond my own memory. I recall that he made a point about his campaign’s momentum (he would eventually win that primary) by joking about how unpopular he had been at the outset: “The first poll had me at 2%, and the margin of error was 5%. So I might have been at minus three.”

I was blogging by the time he ran in the 2008 cycle, so I have this:

He answers questions — even hostile questions — patiently and with empathy. (“Meeting adjourned,” he announces in response to the first gotcha. The room erupts in laughter, and then he answers.) He tells corny jokes and at the same time manages to wink at you, as if the real joke is that you have to tell jokes to win the world’s most serious job. He runs himself down, confessing to being fifth from the bottom of his class at the Naval Academy, saying that his candidacy proves that “in America anything is possible.” And yet no one in the room forgets that he is John McCain, and he has survived things that would have destroyed any mere mortal. It is an amazing balancing act.

McCain invited the two men who defeated his presidential campaigns, Bush and Barack Obama, to speak at his service in the National Cathedral on Saturday. (Trump was eventually invited to attend — by Lindsey Graham, with Cindy McCain’s approval — but spent the day playing golf.) Obama noted McCain’s humor, magnanimity, and respect for opponents:

After all, what better way to get a last laugh than to make George and I say nice things about him to a national audience? And most of all, it showed a largeness of spirit, an ability to see past differences in search of common ground.

Lindsey Graham noted the contrast between McCain’s magnanimity and Trump’s churlish response to McCain’s death. (He raised the White House flag back to full staff until public outrage made him lower it again.)

John McCain was a big man, worthy of a big country. Mr. President, you need to be the big man that the presidency requires.

Obama made a similar point more obliquely:

So much of our politics, our public life, our public discourse can seem small and mean and petty, trafficking in bombast and insult and phony controversies and manufactured outrage. It’s a politics that pretends to be brave and tough, but in fact is born of fear. John called on us to be bigger than that. He called on us to be better than that.

And Bush agreed:

To the face of those in authority, John McCain would insist: We are better than this. America is better than this.

Principle and respect for opponents were stressed by another of those opponents: former Vice President Joe Biden.

The way things changed so much in America, they look at him as if John came from another age, lived by a different code, an ancient, antiquated code where honor, courage, integrity, duty, were alive. That was obvious, how John lived his life. The truth is, John’s code was ageless, is ageless. When you talked earlier, Grant [Woods], you talked about values. It wasn’t about politics with John. He could disagree on substance, but the underlying values that animated everything John did, everything he was, come to a different conclusion. He’d part company with you if you lacked the basic values of decency, respect, knowing this project is bigger than yourself.

For Bush, McCain symbolized America, or at least the America we want to be:

Whatever the cause, it was this combination of courage and decency that defined John’s calling, and so closely paralleled the calling of his country. It’s this combination of courage and decency that makes the American military something new in history, an unrivaled power for good. It’s this combination of courage and decency that set America on a journey into the world to liberate death camps, to stand guard against extremism, and to work for the true peace that comes only with freedom.

And Meghan McCain drew the parallel most clearly, in a litany of statements about “the America of John McCain”, that culminated in:

The America of John McCain is generous and welcoming and bold. She is resourceful, confident, secure. She meets her responsibilities. She speaks quietly because she is strong. America does not boast because she has no need to. The America of John McCain has no need to be made great again because America was always great. That fervent faith, that proven devotion, that abiding love, that is what drove my father from the fiery skies above the Red River delta to the brink of the presidency itself.

McCain the man. Unless we are willing to massage their stories and avert our eyes from unfortunate facts, no actual human being is precisely the hero we need. So it is no insult to point out that the actual John McCain was not that hero.

McCain had a temper and could be verbally abusive. His commitment to campaign finance reform arose out of his own scandal. His opposition to torture was never as complete as it seemed. In order to get the Republican nomination in 2008, he embraced the same evangelical preachers he had called “agents of intolerance” in 2000. He famously corrected a supporter who questioned Obama’s citizenship and religion, but he also empowered Sarah Palin to rouse that same rabble.

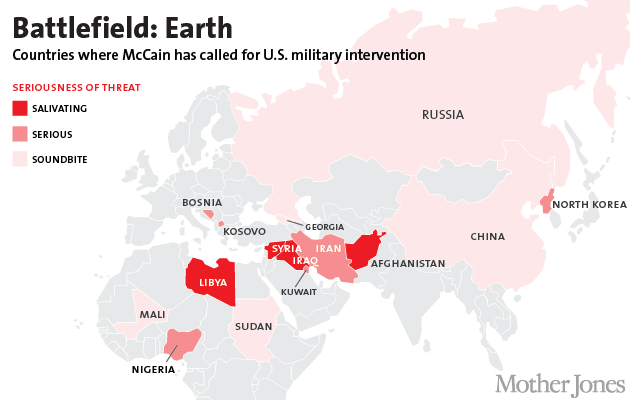

He vigorously supported the Iraq invasion, and opposed Obama’s withdrawal from that war. In 2013, Mother Jones published a map of all the places McCain had threatened with military intervention.

And despite that one key vote against repealing ObamaCare, McCain was not that big of an anti-Trump rebel; he voted with the president 83% of the time — more than 538’s model of his state’s electorate would predict.

He talked a good game against Trump, but how much did he actually do? He was chair of the Senate Armed Services Committee, which had only one more Republican than Democrat. With the Democrats, he could have led an anti-Trump majority. He had subpoena power; any Trump scandal with a national-security angle was within his purview. He did nothing with that power.

So no, the real John McCain was not the hero the Trump Era calls for. He was not the anti-Trump.

Should we be cynical about him? To a large extent, it was McCain himself who orchestrated this celebration of the anti-Trump hero. He had known he was dying, and gave serious thought to his funeral. He invited Bush and Obama to speak and stipulated that Trump not speak. He wrote an explicitly political last message to America.

He knew his death would be a political weapon, and he very intentionally set out to use it. His death, like his life, would serve a purpose bigger than himself.

As his daughter Meghan acknowledged, no one would have been more cynical about such a display than John himself:

Several of you out there in the pews who crossed swords with him or found yourselves on the receiving end of his famous temper or were at a cross purpose to him on nearly anything, are right at this moment doing your best to stay stone-faced. Don’t. You know full well if John McCain were in your shoes today, he would be using some salty word he learned in the Navy while my mother jabbed him in the arm in embarrassment. He would look back at her and grumble, maybe stop talking, but he would keep grinning.

It is tempting to denounce all this, as voices from both the left and the right have. And yet, I will not.

This era needs an anti-Trump hero. The perfect avatar of that ideal has not emerged yet. In the meantime, we have John McCain, whose life in so many ways can remind us of the thing we long for.

We should celebrate that; neither in ignorance nor in cynicism, but in hope. Someday the Trump Era will end. May that day come soon. And if the Legend of John McCain helps it come sooner, then I say: “Print the legend.”

[1] Liberals and conservatives, respectively, often think of George W. Bush and Barack Obama as divisive presidents. But each tried to appeal to those who voted against him.

Bush worked with Ted Kennedy on education policy. The day after winning re-election in 2004, he directed a portion of his speech to supporters of John Kerry: “We have one country, one Constitution and one future that binds us. To make this nation stronger and better, I will need your support, and I will work to earn it.” For his part, Kerry recounted his post-election conversation with Bush: “We talked about the danger of division in our country and the need — the desperate need for unity, for finding the common ground, coming together. Today I hope that we can begin the healing.”

Obama hoped to start his presidency with a bipartisan compromise: His stimulus package was smaller than many advisers recommended, and tax cuts made up about a third of the package. (In the end he got no Republican votes in the House and only three in the Senate.) Later in his term, a variety of “grand bargains” with House Speaker John Boehner attempted to address what (at that time) was the Republicans’ central issue: the long-term budget deficit. But Boehner was never able to pull together enough support within his caucus.

Trump, on the other hand, is still tweeting about “Crooked Hillary”, pushing his Justice Department to prosecute her, and promoting conspiracy theories about the investigation that cleared her. I have tried to think of a similar situation in American history, and I have not come up with one.

[2] Think about where the hush-money story has gone. A long series of denials have collapsed, and Trump no longer bothers to argue about whether he had sexual affairs with Stormy Daniels and Karen McDougal during his marriage to Melania. He admits his lawyer Michael Cohen paid each woman six-figure sums so that they wouldn’t tell their stories before the election. The new line of defense is that the payments weren’t illegal, because the money ultimately came from his personal funds and not from the campaign. That’s how deep in the sleaze the President has gotten. I-paid-her-myself is a defense now.

Remember what a presidential scandal looked like during the Obama years? He put his feet up on an Oval Office desk. He ordered a Marine to hold his umbrella. His Christmas cards were too secular. Michelle wore sleeveless dresses.

[3] I’m intentionally not saying “anti-Christ”, because that evokes all the speculative Book of Revelation interpretations that have distracted so many Christians from Jesus’ teachings. I’m not postulating some end-times role for Trump, I’m just noting that it’s impossible to imagine him saying a single line of the Sermon on the Mount. Well, maybe: “Blessed are you when others revile you and persecute you and utter all kinds of evil against you falsely on my account.” But the rest of it — turn the other cheek, love your enemies, blessed are the meek and the poor in spirit, “do not lay up for yourselves treasures on Earth” — no way.

[4] Something similar could be said about Ranse Stoddard, who really did have the virtues the myth assigned him. He didn’t kill Liberty Valance, but the people who thought he did were not disappointed when they met him.

The political scientist most connected with this idea is Stephen Skowronek, who introduced the concept of “

The political scientist most connected with this idea is Stephen Skowronek, who introduced the concept of “

The City on a Hill. I was home sick on Wednesday, so I spent the day reading a short new book called

The City on a Hill. I was home sick on Wednesday, so I spent the day reading a short new book called