Tea Partiers say you don’t understand them because you don’t understand American history. That’s probably true, but not in the way they want you to think.

Late in 2012, I came out of the Lincoln movie with two historical mysteries to solve:

- How did the two parties switch places regarding the South, white supremacy, and civil rights? In Lincoln’s day, a radical Republican was an abolitionist, and when blacks did get the vote, they almost unanimously voted Republican. Today, the archetypal Republican is a Southern white, and blacks are almost all Democrats. How did American politics get from there to here?

- One of the movie’s themes was how heavily the war’s continuing carnage weighed on Lincoln. (It particularly came through during Grant’s guided tour of the Richmond battlefield.) Could any cause, however lofty, justify this incredible slaughter? And yet, I realized, Lincoln was winning. What must the Confederate leaders have been thinking, as an even larger percentage of their citizens died, as their cities burned, and as the accumulated wealth of generations crumbled? Where was their urge to end this on any terms, rather than wait for complete destruction?

The first question took some work, but yielded readily to patient googling. I wrote up the answer in “A Short History of White Racism in the Two-Party System“. The second turned out to be much deeper than I expected, and set off a reading project that has eaten an enormous amount of my time over the last two years. (Chunks of that research have shown up in posts like “Slavery Lasted Until Pearl Harbor“, “Cliven Bundy and the Klan Komplex“, and my review of Ta-Nehisi Coates’ article on reparations.) Along the way, I came to see how I (along with just about everyone I know) have misunderstood large chunks of American history, and how that misunderstanding clouds our perception of what is happening today.

Who really won the Civil War? The first hint at how deep the second mystery ran came from the biography Jefferson Davis: American by William J. Cooper. In 1865, not only was Davis not agonizing over how to end the destruction, he wanted to keep it going longer. He disapproved of Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, and when U. S. troops finally captured him, he was on his way to Texas, where an intact army might continue the war.

Who really won the Civil War? The first hint at how deep the second mystery ran came from the biography Jefferson Davis: American by William J. Cooper. In 1865, not only was Davis not agonizing over how to end the destruction, he wanted to keep it going longer. He disapproved of Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, and when U. S. troops finally captured him, he was on his way to Texas, where an intact army might continue the war.

That sounded crazy until I read about Reconstruction. In my high school history class, Reconstruction was a mysterious blank period between Lincoln’s assassination and Edison’s light bulb. Congress impeached Andrew Johnson for some reason, the transcontinental railroad got built, corruption scandals engulfed the Grant administration, and Custer lost at Little Big Horn. But none of it seemed to have much to do with present-day events.

And oh, those blacks Lincoln emancipated? Except for Booker T. Washington and George Washington Carver, they vanished like the Lost Tribes of Israel. They wouldn’t re-enter history until the 1950s, when for some reason they still weren’t free.

Here’s what my teachers’ should have told me: “Reconstruction was the second phase of the Civil War. It lasted until 1877, when the Confederates won.” I think that would have gotten my attention.

It wasn’t just that Confederates wanted to continue the war. They did continue it, and they ultimately prevailed. They weren’t crazy, they were just stubborn.

The Lost Cause. At about the same time my American history class was leaving a blank spot after 1865, I saw Gone With the Wind, which started filling it in like this: Sadly, the childlike blacks weren’t ready for freedom and full citizenship. Without the discipline of their white masters, many became drunks and criminals, and they raped a lot of white women. Northern carpetbaggers used them (and no-account white scalawags) as puppets to control the South, and to punish the planter aristocrats, who prior to the war had risen to the top of Southern society through their innate superiority and virtue.

The Lost Cause. At about the same time my American history class was leaving a blank spot after 1865, I saw Gone With the Wind, which started filling it in like this: Sadly, the childlike blacks weren’t ready for freedom and full citizenship. Without the discipline of their white masters, many became drunks and criminals, and they raped a lot of white women. Northern carpetbaggers used them (and no-account white scalawags) as puppets to control the South, and to punish the planter aristocrats, who prior to the war had risen to the top of Southern society through their innate superiority and virtue.

But eventually the good men of the South could take it no longer, so they formed the Ku Klux Klan to protect themselves and their communities. They were never able to restore the genteel antebellum society — that Eden was gone with the wind, a noble but ultimately lost cause — but they were eventually able to regain the South’s honor and independence. Along the way, they relieved their beloved black servants of the onerous burden of political equality, until such time as they might become mature enough to bear it responsibly.

A still from The Birth of a Nation

That telling of history is now named for its primary proponent, William Dunning. It is false in almost every detail. If history is written by the winners, Dunning’s history is the clearest evidence that the Confederates won. [see endnote 1]

Margaret Mitchell’s 1936 novel had actually toned it down a little. To feel the full impact of Dunning-school history, you need to read Thomas Dixon’s 1905 best-seller, The Clansman: a historical romance of the Ku Klux Klan. Or watch the 1915 silent movie made from it, The Birth of a Nation, which was the most popular film of all time until Gone With the Wind broke its records.

The iconic hooded Klansman on his horse, the Knight of the Invisible Empire, was the Luke Skywalker of his day.

The first modern war. The Civil War was easy to misunderstand at the time, because there had never been anything like it. It was a total mobilization of society, the kind Europe wouldn’t see until World War I. The Civil War was fought not just with cannons and bayonets, but with railroads and factories and an income tax.

If the Napoleonic Wars were your model, then it was obvious that the Confederacy lost in 1865: Its capital fell, its commander surrendered, its president was jailed, and its territories were occupied by the opposing army. If that’s not defeat, what is?

If the Napoleonic Wars were your model, then it was obvious that the Confederacy lost in 1865: Its capital fell, its commander surrendered, its president was jailed, and its territories were occupied by the opposing army. If that’s not defeat, what is?

But now we have a better model than Napoleon: Iraq.

After the U.S. forces won on the battlefield in 1865 and shattered the organized Confederate military, the veterans of that shattered army formed a terrorist insurgency that carried on a campaign of fire and assassination throughout the South until President Hayes agreed to withdraw the occupying U. S. troops in 1877. Before and after 1877, the insurgents used lynchings and occasional pitched battles to terrorize those portions of the electorate still loyal to the United States. In this way they took charge of the machinery of state government, and then rewrote the state constitutions to reverse the postwar changes and restore the supremacy of the class that led the Confederate states into war in the first place. [2]

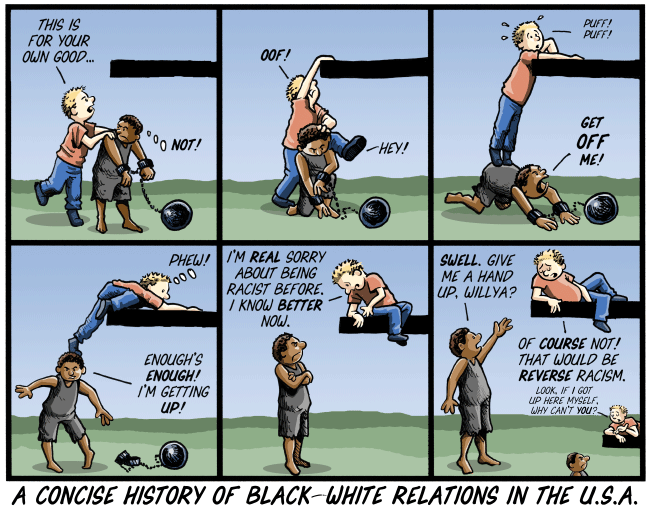

By the time it was all over, the planter aristocrats were back in control, and the three constitutional amendments that supposedly had codified the U.S.A’s victory over the C.S.A.– the 13th, 14th, and 15th — had been effectively nullified in every Confederate state. The Civil Rights Acts had been gutted by the Supreme Court, and were all but forgotten by the time similar proposals resurfaced in the 1960s. Blacks were once again forced into hard labor for subsistence wages, denied the right to vote, and denied the equal protection of the laws. Tens of thousands of them were still physically shackled and subject to being whipped, a story historian Douglas Blackmon told in his Pulitzer-winning Slavery By Another Name.

So Lincoln and Grant may have had their mission-accomplished moment, but ultimately the Confederates won. The real Civil War — the one that stretched from 1861 to 1877 — was the first war the United States lost.

In particular, 1865 was a moment when reparations and land reform were actually feasible. Late in the war, some of Lincoln’s generals — notably Sherman — had mitigated their slave-refugee problem by letting emancipated slaves farm small plots on the plantations that had been abandoned by their Confederate owners. Sick or injured animals unable to advance with the Army were left behind for the slaves to nurse back to health and use. (Hence “forty acres and a mule”.) Sherman’s example might have become a land-reform model for the entire Confederacy, dispossessing the slave-owning aristocrats in favor of the people whose unpaid labor had created their wealth.

Instead, President Johnson (himself a former slave-owner from Tennessee) was quick to pardon the aristocrats and restore their lands. [3] That created a dynamic that has been with us ever since: Early in Reconstruction, white and black working people sometimes made common cause against their common enemies in the aristocracy. But once it became clear that the upper classes were going to keep their ill-gotten holdings, freedmen and working-class whites were left to wrestle over the remaining slivers of the pie. Before long, whites who owned little land and had never owned slaves had become the shock troops of the planters’ bid to restore white supremacy.

Along the way, the planters created rhetoric you still hear today: The blacks were lazy and would rather wait for gifts from the government than work (in conditions very similar to slavery). In this way, the idle planters were able to paint the freedmen as parasites who wanted to live off the hard work of others.

The larger pattern. But the enduring Confederate influence on American politics goes far beyond a few rhetorical tropes. The essence of the Confederate worldview is that the democratic process cannot legitimately change the established social order, and so all forms of legal and illegal resistance are justified when it tries.

That worldview is alive and well. During last fall’s government shutdown and threatened debt-ceiling crisis, historian Garry Wills wrote about our present-day Tea Partiers: “The presiding spirit of this neo-secessionism is a resistance to majority rule.”

The Confederate sees a divinely ordained way things are supposed to be, and defends it at all costs. No process, no matter how orderly or democratic, can justify fundamental change.

When in the majority, Confederates protect the established order through democracy. If they are not in the majority, but have power, they protect it through the authority of law. If the law is against them, but they have social standing, they create shams of law, which are kept in place through the power of social disapproval. If disapproval is not enough, they keep the wrong people from claiming their legal rights by the threat of ostracism and economic retribution. If that is not intimidating enough, there are physical threats, then beatings and fires, and, if that fails, murder.

That was the victory plan of Reconstruction. Black equality under the law was guaranteed by the 14th Amendment. But in the Confederate mind, no democratic process could legitimate such a change in the social order. It simply could not be allowed to stand, and it did not stand.

In the 20th century, the Confederate pattern of resistance was repeated against the Civil Rights movement. And though we like to claim that Martin Luther King won, in many ways he did not. School desegregation, for example, was never viewed as legitimate, and was resisted at every level. And it has been overcome. By most measures, schools are as segregated as ever, and the opportunities in white schools still far exceed the opportunities in non-white schools.

Today, ObamaCare cannot be accepted. No matter that it was passed by Congress, signed by the President, found constitutional by the Supreme Court, and ratified by the people when they re-elected President Obama. It cannot be allowed to stand, and so the tactics for destroying it get ever more extreme. The point of violence has not yet been reached, but the resistance is still young.

Today, ObamaCare cannot be accepted. No matter that it was passed by Congress, signed by the President, found constitutional by the Supreme Court, and ratified by the people when they re-elected President Obama. It cannot be allowed to stand, and so the tactics for destroying it get ever more extreme. The point of violence has not yet been reached, but the resistance is still young.

Violence is a key component of the present-day strategy against abortion rights, as Judge Myron Thompson’s recent ruling makes clear. Legal, political, social, economic, and violent methods of resistance mesh seamlessly. The Alabama legislature cannot ban abortion clinics directly, so it creates reasonable-sounding regulations the clinics cannot satisfy, like the requirement that abortionists have admitting privileges at local hospitals. Why can’t they fulfill that requirement? Because hospitals impose the reasonable-sounding rule that their doctors live and practice nearby, while many Alabama abortionists live out of state. The clinics can’t replace them with local doctors, because protesters will harass the those doctors’ non-abortion patients and drive the doctors out of any business but abortion. A doctor who chooses that path will face threats to his/her home and family. And doctors who ignore such threats have been murdered.

Legislators, of course, express horror at the murder of doctors, just as the pillars of 1960s Mississippi society expressed horror at the Mississippi Burning murders, and the planter aristocrats shook their heads sadly at the brutality of the KKK and the White Leagues. But the strategy is all of a piece and always has been. Change cannot stand, no matter what documents it is based on or who votes for them. If violence is necessary, so be it.

Unbalanced. This is not a universal, both-sides-do-it phenomenon. Compare, for example, the responses to the elections of our last two presidents. Like many liberals, I will go to my grave believing that if every person who went to the polls in 2000 had succeeded in casting the vote s/he intended, George W. Bush would never have been president. I supported Gore in taking his case to the courts. And, like Gore, once the Supreme Court ruled in Bush’s favor — incorrectly, in my opinion — I dropped the issue.

For liberals, the Supreme Court was the end of the line. Any further effort to replace Bush would have been even less legitimate than his victory. Subsequently, Democrats rallied around President Bush after 9/11, and I don’t recall anyone suggesting that military officers refuse his orders on the grounds that he was not a legitimate president.

Barack Obama, by contrast, won a huge landslide in 2008, getting more votes than any president in history. And yet, his legitimacy has been questioned ever since. The Birther movement was created out of whole cloth, there never having been any reason to doubt the circumstances of Obama’s birth. Outrageous conspiracy theories of voter fraud — millions and millions of votes worth — have been entertained on no basis whatsoever. Immediately after Obama took office, the Oath Keeper movement prepared itself to refuse his orders.

A black president calling for change, who owes most of his margin to black voters — he himself is a violation of the established order. His legitimacy cannot be conceded.

Confederates need guns. The South is a place, but the Confederacy is a worldview. To this day, that worldview is strongest in the South, but it can be found all over the country (as are other products of Southern culture, like NASCAR and country music). A state as far north as Maine has a Tea Party governor.

Gun ownership is sometimes viewed as a part of Southern culture, but more than that, it plays a irreplaceable role in the Confederate worldview. Tea Partiers will tell you that the Second Amendment is our protection against “tyranny”. But in practice tyranny simply means a change in the established social order, even if that change happens — maybe especially if it happens — through the democratic processes defined in the Constitution. If the established social order cannot be defended by votes and laws, then it will be defended by intimidation and violence. How are We the People going to shoot abortion doctors and civil rights activists if we don’t have guns?

Gun ownership is sometimes viewed as a part of Southern culture, but more than that, it plays a irreplaceable role in the Confederate worldview. Tea Partiers will tell you that the Second Amendment is our protection against “tyranny”. But in practice tyranny simply means a change in the established social order, even if that change happens — maybe especially if it happens — through the democratic processes defined in the Constitution. If the established social order cannot be defended by votes and laws, then it will be defended by intimidation and violence. How are We the People going to shoot abortion doctors and civil rights activists if we don’t have guns?

Occasionally this point becomes explicit, as when Nevada Senate candidate Sharron Angle said this:

You know, our Founding Fathers, they put that Second Amendment in there for a good reason and that was for the people to protect themselves against a tyrannical government. And in fact Thomas Jefferson said it’s good for a country to have a revolution every 20 years. I hope that’s not where we’re going, but, you know, if this Congress keeps going the way it is, people are really looking toward those Second Amendment remedies and saying my goodness what can we do to turn this country around? I’ll tell you the first thing we need to do is take Harry Reid out.

Angle wasn’t talking about anything more “tyrannical” than our elected representatives voting for things she didn’t like (like ObamaCare or stimulus spending). If her side can’t fix that through elections, well then, the people who do win those elections will just have to be intimidated or killed. Angle doesn’t want it to come to that, but if liberals won’t yield peacefully to the conservative minority, what other choice is there?

Gun-rights activist Larry Pratt doesn’t even seem regretful:

“The Second Amendment is not for hunting, it’s not even for self-defense,” Pratt explained in his Leadership Institute talk. Rather, it is “for restraining tyrannical tendencies in government. Especially those in the liberal, tyrannical end of the spectrum. There is some restraint, and even if the voters of Brooklyn don’t hold them back, it may be there are other ways that their impulses are somewhat restrained. That’s the whole idea of the Second Amendment.”

So the Second Amendment is there not to defend democracy, but to fix what the progressive “voters of Brooklyn” get wrong.

It’s not a Tea Party. The Boston Tea Party protest was aimed at a Parliament where the colonists had no representation, and at an appointed governor who did not have to answer to the people he ruled. Today’s Tea Party faces a completely different problem: how a shrinking conservative minority can keep change at bay in spite of the democratic processes defined in the Constitution. That’s why they need guns. That’s why they need to keep the wrong people from voting in their full numbers.

It’s not a Tea Party. The Boston Tea Party protest was aimed at a Parliament where the colonists had no representation, and at an appointed governor who did not have to answer to the people he ruled. Today’s Tea Party faces a completely different problem: how a shrinking conservative minority can keep change at bay in spite of the democratic processes defined in the Constitution. That’s why they need guns. That’s why they need to keep the wrong people from voting in their full numbers.

These right-wing extremists have misappropriated the Boston patriots and the Philadelphia founders because their true ancestors — Jefferson Davis and the Confederates — are in poor repute. [4]

But the veneer of Bostonian rebellion easily scrapes off; the tea bags and tricorn hats are just props. The symbol Tea Partiers actually revere is the Confederate battle flag. Let a group of right-wingers ramble for any length of time, and you will soon hear that slavery wasn’t really so bad, that Andrew Johnson was right, that Lincoln shouldn’t have fought the war, that states have the rights of nullification and secession, that the war wasn’t really about slavery anyway, and a lot of other Confederate mythology that (until recently) had left me asking, “Why are we talking about this?”

By contrast, the concerns of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and its revolutionary Sons of Liberty are never so close to the surface. So no. It’s not a Tea Party. It’s a Confederate Party.

Our modern Confederates are quick to tell the rest of us that we don’t understand them because we don’t know our American history. And they’re right. If you knew more American history, you would realize just how dangerous these people are.

Endnotes

[1] The other clear evidence stands in front of nearly every courthouse in the South: statues of Confederate heroes. You have to be blind not to recognize them as victory monuments. In the Jim Crow era, these stone sentries guarded the centers of civic power against Negroes foolish enough to try to register to vote or claim their other constitutional rights.

Calhoun way up high

In Away Down South: a history of Southern identity, James C. Cobb elaborates:

African Americans understood full well what monuments to the antebellum white regime were all about. When Charleston officials erected a statue of proslavery champion John C. Calhoun, “blacks took that statue personally,” Mamie Garvin Fields recalled. After all, “here was Calhoun looking you in the face and telling you, ‘Nigger, you may not be a slave but I’m back to see you stay in your places.’ ” In response, Fields explained, “we used to carry something with us, if we knew we would be passing that way, in order to deface that statue — scratch up the coat, break up the watch chain, try to knock off the nose. … [C]hildren and adults beat up John C. Calhoun so badly that the whites had to come back and put him way up high, so we couldn’t get to him.”

[2] The vocabulary of this struggle is illuminating. A carpetbagger was a no-account Northerner who arrived in the South with nothing more than the contents of a carpetbag. A scalawag was a lower-class Southern white who tried to rise above his betters in the post-war chaos. The class-based nature of these insults demonstrates who was authorizing this history: the planter aristocrats.

For a defense of the claim that the aristocrats intentionally led the South into war, see Douglas Egerton’s Year of Meteors: Stephen Douglas, Abraham Lincoln, and the Election that Brought on the Civil War.

[3] Though Congress had to find other “high crimes and misdemeanors” for their bill of impeachment, Johnson’s betrayal of the United States’ battlefield victory was the real basis of the attempt to remove him.

[4] Jefferson Davis and the Confederates also misappropriated the Founders. It started with John Calhoun’s Discourse on the Constitution and Government of the United States, published posthumously in 1851, which completely misrepresented the Founders and their Constitution. Calhoun’s view (that the Union was a consortium of states with no direct relationship to the people) would have made perfect sense if the Constitution had begun “We the States” rather than “We the People”.

Calhoun disagreed with Jefferson on one key point: All men are not created equal.

Modern conservatives who attribute their views to the Founders are usually unknowingly relying on Calhoun’s false image of the Founders, which was passed down through Davis and from there spread widely in Confederate folklore.