In every other aspect of life, we assume that the poor can get by with fewer goods of lower quality than the rest of us consume. But when it comes to health insurance, the exact opposite is true.

One common assumption runs through all our anti-poverty programs: The poor and less well-to-do don’t need to live as well as the rest of us. So public housing consists largely of small, poorly appointed apartments in bad neighborhoods, not mansions or suburban ranch houses. It is considered scandalous if food stamps are used to buy luxury foods like steak or lobster, and several states have put long lists of restrictions on how welfare benefits can be spent (even if there’s little evidence they were ever being spent that way). Conservative media often expresses surprise at how many poor families have ordinary modern conveniences like refrigerators and dishwashers, not to mention Xboxes or iPhones.

In its extreme manifestations this attitude becomes petty, but there is also some widely held common sense behind it: If I’m going to pay taxes to support someone else’s lifestyle, at the very least they shouldn’t live better than I do.

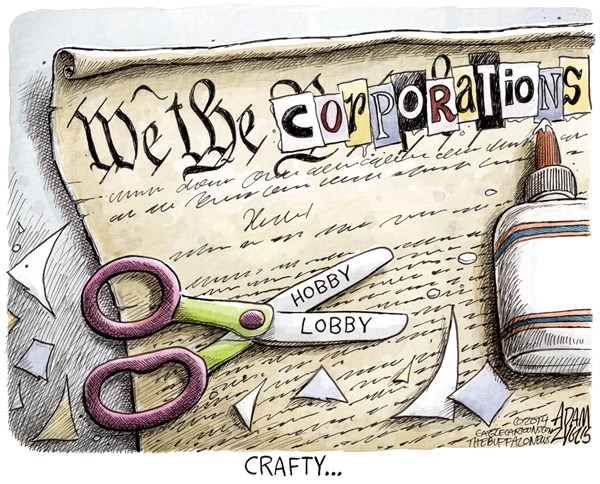

So it’s no surprise that the same idea has percolated through to healthcare policy. It’s not controversial that Medicaid patients lack the same choice of doctors as the rest of us, and may have to wait longer for an appointment. And when ObamaCare offered to subsidize health insurance for families with incomes beyond the Medicaid cut-off (which it tried to increase, but was thwarted in 19 states), the fact that many families could now only afford “bronze” plans, with high co-pays and deductibles, wasn’t a big issue: Shouldn’t they be happy to have health insurance at all?

Now that Republicans control Congress and the presidency, even ObamaCare’s bronze plans are considered too luxurious. Their ObamaCare replacement bill calls for the Medicaid extension to be phased out beginning in 2020, and its block-grant provision puts financial pressure on states to throw more and more people off of Medicaid as the years go by. Health-insurance subsidies for the working poor and lower middle class will be turned into tax credits based on age, not income, and generally made smaller. Regulations will be relaxed so that insurance companies can offer plans with fewer benefits and higher co-pays and deductibles — and presumably lower premiums. Economic necessity will force many low-income families (who will have less government help) into these low-premium, low-benefit, high-co-pay policies, or to forego health insurance altogether.

For many middle-class and upper-class Americans, these facts do not set off alarm bells. After all, it’s just common sense that the poorer people have to get by with less. What’s the advantage of making money if those with lower incomes get the same quality of health insurance we have?

In this article I want to argue that health insurance is a unique commodity, and in this instance our common sense is just wrong: The poorer you are, the better your health insurance needs to be. In this one situation, it’s the poor who should get the mansions and lobsters, while the rest of us occasionally make do with less.

I understand how outrageous that sounds. And in order explain why, I’m going to have to back up and explain the basic logic of insurance in general.

1. Even good insurance is usually a bad deal. The first thing to understand about insurance is that, if it’s going to work at all, it has to be a bad deal for most of the people involved.

That’s easiest to see in the case of fire insurance. The reason fire insurance works is that most people’s houses never burn down. If that weren’t true, if houses were burning down left and right, then insurance companies would have to charge astronomical rates that most people couldn’t afford. But it is true, so fire insurance is affordable.

My parents, for example, were homeowners for almost 60 years, and never filed a fire-insurance claim. Year after year, they paid the insurance company, and the insurance company never paid them. What a crummy deal!

Most homeowners are like that. And even the ones who do file a claim or two in their lifetimes probably still lose out: They have a little kitchen fire that requires replacing some cabinets and countertops — but nothing like the value of a lifetime’s worth of premiums.

So fire insurance is not an investment. Unless you’re planning an arson fraud, you don’t buy it expecting to come out ahead.

Even so, it’s not a stupid thing to do. The reason you buy fire insurance is to protect your vision of the future. The odds of your house burning down might be small, but a house is such a large portion of your net worth that losing it would be catastrophic. Without insurance, not only couldn’t most people rebuild anything like their original home, but everything else they had planned to do with their money — retire, pay for their kids’ education, and so on — would be up in smoke as well. The life they had envisioned before the fire would be over.

2. How much insurance you need depends on how tight your finances are. Whenever you buy an electronic gadget, the store will also try to sell you some kind of insurance. Maybe they’ll call it a “buyer’s protection plan” or an “extended warranty”, but basically it’s insurance: If something bad happens to your new phone or computer or TV, they’ll replace it.

Like all insurance, it’s a bad deal for most people. Unless you’re incredibly unlucky or accident-prone, over your lifetime you’d be better off saving up that extended-warranty money and replacing broken gadgets yourself.

But there’s a situation where you might want to pay for the insurance anyway: Imagine you’re buying a very expensive camera to start your own photography business. You’ve stretched yourself really tight to start this business, so tight that if that camera broke, you wouldn’t be able to replace it and your fledgling business would go down the tubes. Now camera insurance starts to resemble fire insurance on your house: You need it to protect your vision of the future.

In general, the right question to ask when you’re thinking about insurance is: “If I don’t have insurance and the Bad Thing happens, what happens next?” If the answer is: “I’ll replace what I’ve lost and life will go on as before”, then you don’t need insurance. But if it’s “Important aspects of my vision of the future will have to change”, you do. So a typical middle-class American doesn’t need an extended warranty on a $100 camera, but does need fire insurance on a house.

3. If you’re rich, you can do without. This aspect of insurance is hard to wrap your mind around, because it works backwards from most of the other expenses in life. For most goods and services, you expect that if you got richer you’d buy the higher-priced version. If you’re living on mac-and-cheese now, you imagine that if you got rich you’d eat filet mignon. You’d trade in your 10-year-old rust-bucket for a new BMW. The apartment you share with friends would become a sprawling private mansion, and so on. You don’t picture doing without anything.

But rich people can afford to forego insurance that poor and middle-class people need. Think about it: If you own ten houses and can afford to buy ten more, why should you insure any of them? If one of them burns down, it’s like the $100 camera: you’ll just replace it and life will go on. Insurance is a bad deal you can afford not to make.

One place where middle-class people run into this consideration is with collision deductibles on their car insurance. If you have a high deductible, you’re essentially buying less insurance, so your premiums go down. If you can go a number of years without an accident and put aside what you save in premiums, you’ll easily cover a higher deductible.

So a high deductible is a good deal if you can afford it. If you have the money lying around, a $1,000 deductible on your repair bill can be an annoyance soon forgotten. But for the working poor and even many in the middle class, an unexpected $1,000 expense can be catastrophic: You can’t repair the car at all, and then you can’t get to work, and then your life spirals down the drain of poverty.

So a well-to-do person can afford to have less insurance, but a lower-income person needs more.

4. No matter what you owe, bankrupt is bankrupt. For someone who doesn’t have sufficient savings or credit, high-deductible collision insurance can be as bad as no insurance at all. Where a middle-class person might pay $1,000 of a $10,000 repair and be glad to have insurance, a minimum-wage worker could be driven into bankruptcy by a $1,000 expense just as surely as by a $10,000 expense. And bankrupt is bankrupt, so the difference between no insurance and high-deductible insurance becomes completely invisible.

5. Poor people’s bodies work just like rich people’s bodies. One thing that hides poorer people’s greater need for insurance is that richer people own more expensive stuff. So even though a millionaire family could replace an ordinary middle-class house without breaking a sweat, it probably lives in a well-furnished-and-decorated mansion that it can’t easily replace. Ditto for the new Mercedes compared to a burger-flipper’s aging Ford. So even though the rich have many more resources with which to replace losses, the increased scale of their possible losses means that they probably spend more on insurance than the poor do.

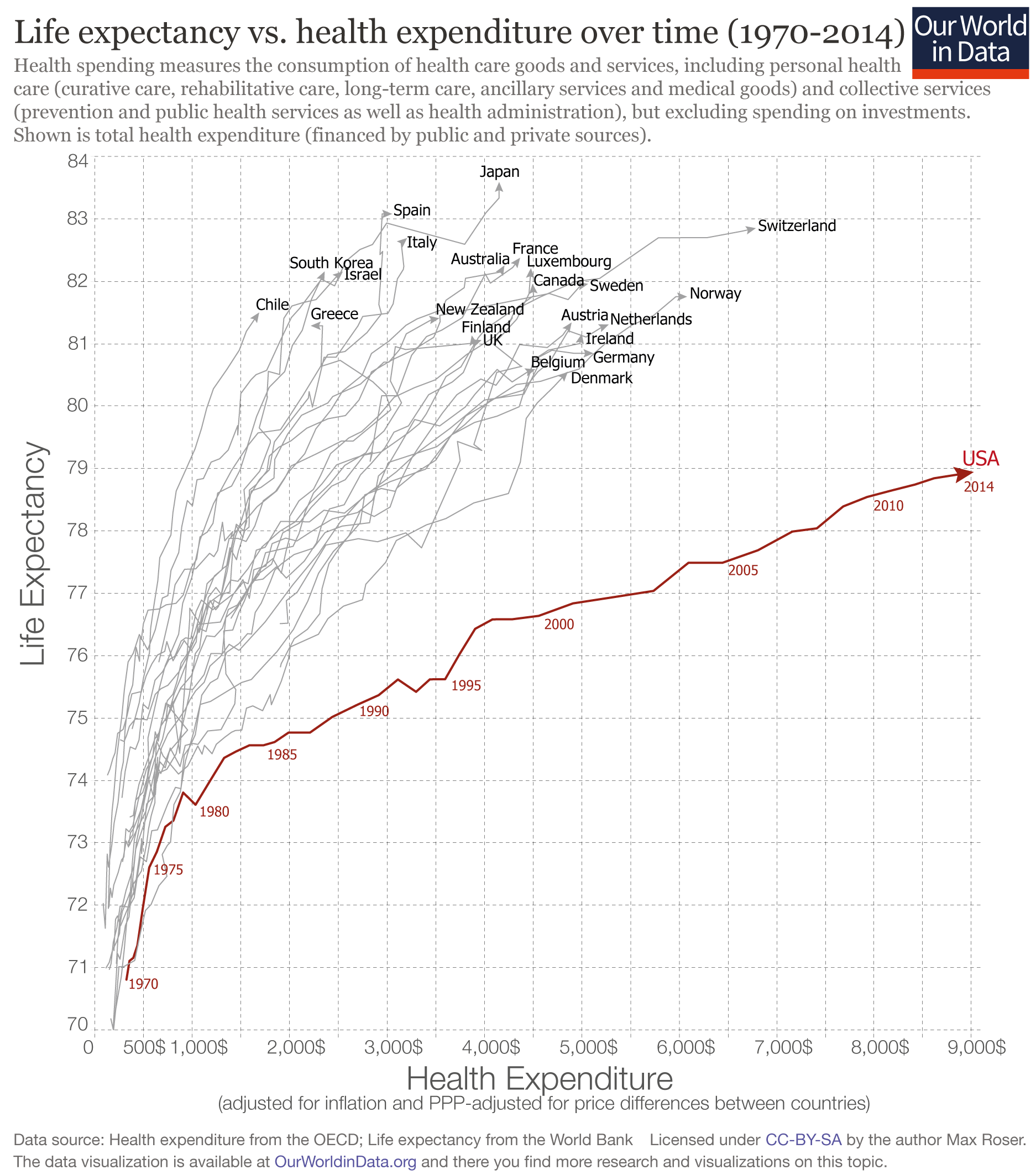

But that reasoning doesn’t apply when you talk about health insurance. A rich guy’s body works just like a poor guy’s body. It’s prone to the same diseases and accidents and breakdowns. (Maybe more, because poor neighborhoods are likely to be more polluted, and low-paying jobs are often riskier than high-paying jobs. Not many mine owners have died of black lung disease.) If she’s going to have the same chance to survive, a poor woman’s breast cancer needs the same treatments as a rich woman’s, and those treatments cost just as much to provide.

6. What is real health insurance? Having health insurance should mean that your vision of your financial future is protected against a health catastrophe. In other words, if you get sick:

- You get the care you need.

- You don’t go bankrupt paying for it.

(Even if you get the care you need, you still might die or wind up unable to work, and that might wreck your vision of your family’s future. But that’s death and disability insurance, which is different topic.)

Most discussions of the Affordable Care Act (a.k.a. ObamaCare) center on the number of uninsured: By some estimates there were 49 million Americans uninsured before the ACA, and that number has come down by something like 20-25 million. Similarly, the percentage of Americans who tell Gallup that they’re uninsured has dropped from 18% in 2013 (before ObamaCare fully took effect) to 10.9% at the end of 2016.

What the uninsured rate ignores, though, is that many of the people who thought they were insured before the ACA only had insurance only up to a point. Millions had policies with annual or lifetime caps on the benefits, or provisions that allowed the insurance company to drop them if they got too sick. In other words, they were covered if they broke a leg slipping on the ice, but they still faced bankruptcy if they waged a multi-year battle with cancer or an expensive chronic disease like MS or HIV.

What the uninsured rate ignores, though, is that many of the people who thought they were insured before the ACA only had insurance only up to a point. Millions had policies with annual or lifetime caps on the benefits, or provisions that allowed the insurance company to drop them if they got too sick. In other words, they were covered if they broke a leg slipping on the ice, but they still faced bankruptcy if they waged a multi-year battle with cancer or an expensive chronic disease like MS or HIV.

The best article about this is a Time cover story from March, 2009: Time‘s reporter on the healthcare-reform beat, Karen Tumulty, recounted how her brother thought he was insured until he was diagnosed with a chronic kidney disease.

When we talk about health-care reform, we usually start with the problem of the roughly 45 million (and rising) uninsured Americans who have no health coverage at all. But [Tumulty’s brother] Pat represents the shadow problem facing an additional 25 million people who spend more than 10% of their income on out-of-pocket medical costs. They are the underinsured, who may be all the more vulnerable because, until a health catastrophe hits, they’re often blind to the danger they’re in.

… While Pat had been continuously covered since 2002 by the same company, Assurant Health, each successive policy treated him as a brand-new customer. In looking back over Pat’s medical records, the company noticed test results from December, eight months earlier. Though Pat’s doctors didn’t determine the precise cause of the problem until the following July, his kidney disease was nonetheless judged a “pre-existing condition” — meaning his insurance wouldn’t cover it, since he was now under a different six-month policy from the one he had when he got those first tests.

The ACA did several things to turn kinda-sorta insurance like this into real insurance: eliminate caps and cancellations, as well as waivers that allowed insurance not to pay for pre-existing conditions. But there’s still a flaw.

7. Deductibles and co-pays. Just like car insurance, a healthcare policy might have a deductible: The company will only start paying after you’ve covered the first $500 or $5000 of your healthcare expenses for the year. The policy might also require co-pays: If you have 10% co-pay and run up a $1000 bill, you have to pay $100 of it.

Put together, those are called “out-of-pocket costs”, and they work just like the deductible on your car insurance: By accepting a higher out-of-pocket cost, you’re buying less insurance, so you’ll be charged a smaller premium.

And since insurance is a bad deal for most people, buying less insurance is a good deal for most people if you can afford it.

If you’re a middle-aged middle-class person and you have to pay the first $5,000 of the $200,000 treatments that cure your cancer, you’ll use the money you were saving for your next car or vacation, or get a home equity loan, or tap your IRA — and thank God you have insurance. If you’re too young to have established yourself financially yet, maybe you’ll stretch your credit cards and your middle-class parents will have to pitch in, but you’ll cover the $5,000 somehow.

Now suppose you’re a minimum-wage worker with no savings, no house, no credit, and no IRA, whose parents are in no better financial shape. To you, $5,000 is an astronomical sum; you can’t pay it, so you’ll have to go bankrupt. And bankrupt is bankrupt, whether it’s for $5,000 or $200,000.

So financially, your insurance has done you no good at all.

8. What does “affordable” really mean? ObamaCare caps out-of-pocket costs, but at a level that can be unapproachable for the working poor and lower-middle-class. The 2017 out-of-pocket limit is $7,150 for an individual or $14,300 for a family. That’s fine if you’re healthy, reasonably well off, and could afford a lower-out-of-pocket plan, but figure that you’ll come out ahead in the long run by buying less insurance. But if you’re forced into that plan because that’s the largest premium you can cover, you’re in a Catch-22: The only plan you can afford to pay the premiums on is one that you can’t afford to use.

8. What does “affordable” really mean? ObamaCare caps out-of-pocket costs, but at a level that can be unapproachable for the working poor and lower-middle-class. The 2017 out-of-pocket limit is $7,150 for an individual or $14,300 for a family. That’s fine if you’re healthy, reasonably well off, and could afford a lower-out-of-pocket plan, but figure that you’ll come out ahead in the long run by buying less insurance. But if you’re forced into that plan because that’s the largest premium you can cover, you’re in a Catch-22: The only plan you can afford to pay the premiums on is one that you can’t afford to use.

Fortunately, the designers of ObamaCare took that into account (at least up to a point). If your income is below a certain level — currently $29,700 for an individual and $60,750 for a family of four, increasing with each additional family member — you qualify for an additional out-of-pocket cost reduction: Below 4/5 of that number, the 2015 limit was $2,250 for an individual and $4,500 for a family, then increasing to $5,200 and $10,400. (Presumably, the 2017 limit has gone up with inflation, but I couldn’t lay my hands on it.)

I still have trouble imagining how a person making $23,760 a year comes up with $2,250, but at least it’s less than $7,150.

But that reduction is part of the income-based subsidies that are going away under TrumpCare. (This was hard to track down, but the web site ObamaCareFacts.com has a TrumpCare page that says: “The bill … gets rid of out-of-pocket cost assistance.”) So if you could imagine someone near the federal poverty limit wriggling through the Catch-22 of ObamaCare, that door is shut under TrumpCare.

9. TrumpCare slams the door on the working poor. For now, the very poor still have Medicaid, which is designed to have low out-of-pocket costs. But TrumpCare eventually jettisons federal responsibility for Medicaid, instead giving the states block grants whose value will not keep up with healthcare inflation. So whether Medicaid will remain as usable as it is now will depend on what state you’re in.

But those just above the Medicaid level — the people who get subsidies in the ObamaCare markets now — are going to wind up without usable insurance. Because they are less well off than the average American, their need for insurance is greater: They need not just coverage, but coverage whose out-of-pocket costs they can handle. A policy that would be fine for a rich or middle-class family will do them no good at all.

The relaxed regulations on coverages and out-of-pocket costs will probably bring premiums down somewhat, but that will only create the illusion of health insurance. Many will still face the horrible choice between foregoing treatment and going bankrupt. In other words, they won’t really be insured at all.

Up until now I’ve been unwilling to make this claim,

Up until now I’ve been unwilling to make this claim,

What the uninsured rate ignores, though, is that many of the people who thought they were insured before the ACA only had insurance only up to a point. Millions had policies with annual or lifetime caps on the benefits, or provisions that allowed the insurance company to drop them if they got too sick. In other words, they were covered if they broke a leg slipping on the ice, but they still faced bankruptcy if they waged a multi-year battle with cancer or an expensive chronic disease like MS or HIV.

What the uninsured rate ignores, though, is that many of the people who thought they were insured before the ACA only had insurance only up to a point. Millions had policies with annual or lifetime caps on the benefits, or provisions that allowed the insurance company to drop them if they got too sick. In other words, they were covered if they broke a leg slipping on the ice, but they still faced bankruptcy if they waged a multi-year battle with cancer or an expensive chronic disease like MS or HIV.

Again

Again