After same-sex marriage, is polygamy a further slide down the slippery slope, the next step of progress, or a separate issue entirely?

After same-sex marriage, is polygamy a further slide down the slippery slope, the next step of progress, or a separate issue entirely?

For the last 10-15 years, people who brought polygamy into a discussion were usually talking about something else. Polygamy was supposedly the next stop on the slippery slope we would step onto if we legalized same-sex marriage: Once you start fiddling with the definition of marriage, the doomsayers prophesied, there is no clear place to stop. In the Supreme Court’s recent marriage decision, Chief Justice Roberts brought that argument into his dissent:

One immediate question invited by the majority’s position is whether States may retain the definition of marriage as a union of two people.

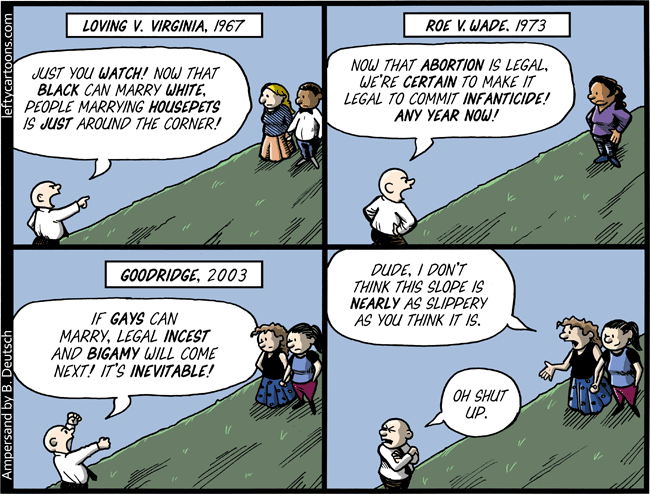

Slippery-slope arguments are often a way to create flashy distractions from the issues that are actually present: If you have no coherent case to make about why a loving, committed same-sex couple shouldn’t be married, you talk instead about legalized polygamy, incest, pedophilia, and bestiality. Maybe no one is actually making those proposals yet, but they could at some point down the road.

On the other hand, some slippery-slope arguments actually are prophetic. In his Lawrence dissent in 2003, Justice Scalia warned:

This reasoning leaves on pretty shaky grounds state laws limiting marriage to opposite-sex couples.

Twelve years later, here we are.

And sometimes, when we look back on prophets of doom, our modern eyes see them as unintentional prophets of progress. The downward slide they feared, we recall proudly. For example, shortly after the Civil War, Rev. R. L. Dabny published a retrospective justification of slavery and secession: A Defence of Virginia. In it he warned the North of the horrors its abolitionist notions would ultimate bring to pass:

But other consequences follow from the abolitionist dogma. “All involuntary restraint is a sin against natural rights,” therefore laws which give to husbands more power over the persons and property of wives, than to wives over husbands, are iniquitous, and should be abolished. The same decision must be made upon the exclusion of women, whether married or single, from suffrage, office, and the full franchises of men. … But when God’s ordinance of the family is thus uprooted, and all the appointed influences of education thus inverted; when America has had a generation of women who were politicians, instead of mothers, how fundamental must be the destruction of society, and how distant and difficult must be the remedy!

Wives owning property! Women voting and running for office! Surely society must collapse from the unnatural strain of such abominations. Why didn’t we listen when Dabny warned us? If only we’d kept blacks in slavery, we could have avoided all this.

[You knew that was sarcasm, right?]

So OK: But for a few dead-enders, same-sex marriage is a done deal now. So polygamy’s usefulness as a slippery-slope horror is over. But are the predictions correct? Is that where we’re heading next? And if we get there, will it be a downward slide or an upward climb?

In Politico Magazine, Fredrik deBoer got right to work with “It’s Time to Legalize Polygamy“. Jonathan Rauch then answered with “No, Polygamy Isn’t the Next Gay Marriage“. And deBoer responded on his blog with “every bad argument against polygamy, debunked“. Another worthwhile piece promoting polygamy (with a better collection of links) is William E. Smith’s “Who’s Scared of Polygamy?” on Religion Dispatches.

I’m not going to take a pro or con position, but I would like to shape the discussion a little.

If you’re worrying (or hoping) that some judge will legalize polygamy next week, stop. Think about how hard it would have been to implement same-sex marriage during the Washington administration: At the dawn of the American Republic, men and women had different legal rights, and husband and wife were unequal legal roles. Same-sex marriage would have been absurd then, because women were legally incapable of playing the husband role, and before they could become wives, men would have to give up inalienable constitutional rights. To make same-sex marriage legal then, the whole legal relationship of men and women — which was embedded in countless laws — would have had to change.

But everything was different by 2003, when the Massachusetts Supreme Court considered the question. Massachusetts had passed an Equal Rights Amendment into its Constitution in 1976, so men and women were equal under the law. The U.S. Supreme Court had thrown out Louisiana’s Head and Master law in 1981, so husband and wife were legal equals. All that really had to happen to make same-sex marriage a reality was to change the forms from Husband and Wife to Spouse and Spouse.

(You can accurately describe American marriage after 1981 in a lot of ways, but “traditional marriage” is not one of them. I don’t know of any traditional society where husbands and wives have been equal under the law.)

Polygamy today resembles same-sex marriage in the Washington administration. Changing the forms to allow an indefinite number of spouses wouldn’t come close to defining it. Are we talking about Biblical (or Mormon) polygamy, where one man marries several women? Jacob and Leah and Rachel, say, or Solomon with his “seven hundred wives of royal birth and three hundred concubines“? Or a group marriage where everybody listed is married to everybody else? Or maybe a chain marriage, where Bob marries Carol marries Ted marries Alice, but Bob and Alice are just friends? Or is some central couple the prime relationship, with other spouses secondary? The possibilities are endless, and the law would have to account for them.*

However you picture it, giving polygamy legal recognition would mean establishing legal infrastructure to answer questions that don’t come up in binary marriages. In a group marriage, can one spouse divorce the others, or does the whole relationship dissolve and need to be reformed? What’s the property settlement look like? Do all spouses have equal rights and responsibilities regarding the children, or do biological parents have a stronger legal bond? In a Biblical polygamous marriage, are all the wives equal, or does the first wife have a special role?

In any of the polygamy models, it doesn’t take much imagination to spin out questions that may not be unanswerable, but aren’t answered in any obvious way by current law. Such questions go all the way down to the most trivial level: What fee should a clerk charge for a plural marriage license? Are current fees based on per-person or per-marriage logic? That question never comes up as long as all marriages are between two people, but someone would need to decide God-knows-how-many minor issues like that.

Consequently, a court can’t simply order to a county clerk to issue a three-person marriage license. The judge would have to rewrite big chunks of the legal code, which a judge is not equipped to do, even if one thought he or she could get away with asserting that kind of power.

Is polygamy a legal right? A somewhat more realistic fantasy/nightmare goes like this: A judge might find that three or more people have a right to the legal advantages marriage offers, even if the judge can’t say exactly how that right should be implemented. That would have to go through a legislature, which is equipped and empowered to rewrite large chunks of the legal code.

So a judge could order the legislature to rectify the situation within a specified time. The legislature would probably refuse, and then the judge could assess damages against the state, which the governor could refuse to pay, and from there who knows where it all goes.

A key part of that scenario, though, is that the legal argument for a right to polygamy is sitting there inside the same-sex-marriage jurisprudence, waiting for some bold judge to notice it. In spite of John Roberts’ dissent, I don’t think that’s true.

In order to have this discussion, though, we need to set aside the particular opinion Justice Kennedy wrote, which really is as bad as the dissents claim. (I covered that when it came out.) It’s not at all typical of marriage-equality opinions, and it contains little in the way of a legal framework that could be extended to polygamy or anything else. I suspect it will have the same kind of influence that Kennedy’s similarly mushy DOMA opinion had: In subsequent lower-court decisions, judges made their rulings consistent with the outcome of the DOMA case, but didn’t attempt to apply Kennedy’s reasoning, such as it was.

The way pro-marriage-equality judges other than Kennedy have approached the issue is through the equal protection of the laws, a position I summarized in May: The opposite-sex marriage laws create an advantageous institution (marriage) and extend its benefits only to opposite-sex couples, when same-sex couples could be included by simply editing the license form, and no credible evidence suggested that negative consequences relevant to the mission of the government would ensue. (The possible offense to God claimed by anti-gay activists is not something the Constitution instructs the government to take notice of. Read the Preamble.) Under those circumstances, there’s really no way to claim that gays and lesbians are being granted the equal protection of the laws promised by the 14th Amendment.

What lies in the background of that argument is that the separation between gays/lesbians and the benefits of marriage is not something the affected individuals can easily fix on their own. Sexual orientation may or may not be innate, but it is not generally changeable in adulthood. And while legally, a gay or lesbian person could enter into a marriage with someone of the opposite sex, it’s hard to see that as a satisfactory solution. Consequently, because of who you are, you might be unable to take advantage of the marriage laws.

What lies in the background of that argument is that the separation between gays/lesbians and the benefits of marriage is not something the affected individuals can easily fix on their own. Sexual orientation may or may not be innate, but it is not generally changeable in adulthood. And while legally, a gay or lesbian person could enter into a marriage with someone of the opposite sex, it’s hard to see that as a satisfactory solution. Consequently, because of who you are, you might be unable to take advantage of the marriage laws.

That argument is much harder to make for polygamy, which feels more like a lifestyle choice than an innate orientation. The government set up an advantageous path hoping to induce you to live one way, but you decided to live another way. I would defend your right to make that choice, but I don’t see how it gives you a right to the advantages of the other lifestyle.

Maybe some other legal argument for a right-to-polygamy is possible, but I don’t know what it is. I think you’d need to show that favoring binary relationships is an irrational thing for the government to do, and can’t conceivably lead to any social benefit the government might reasonably want to achieve. Constructing such an argument would be much harder than just cutting and pasting from the same-sex marriage arguments.

If polygamy isn’t a right. If polygamy isn’t a right inherent in the laws currently on the books, then if people want it, they need to convince legislatures to pass new laws. And that means convincing a large chunk of the electorate (who may or may not have polygamous fantasies) that a society that openly includes polygamous households is better — or at least no worse — than the society we have now.

If we’re debating in a legislature rather than before a judge, then I think the burden of proof shifts a little on both sides. To win in court, a polygamy supporter would need to show that banning it is completely irrational. To win in a legislature, they’d just need to argue that allowing it makes more sense than banning it. deBoer sums up:

my argument for polygamy is that there are people in the world who want it, and I recognize the inherent and total equality of the dignity and value of their relationships in comparison to two-person relationships.

As in same-sex marriage, we’re talking about real people doing real things. What’s our basis for telling them not to? I’m not saying there is no basis, I just can’t explain what it is off the top of my head.

On the other side, a legislature would have to debate a real proposal, not just an idea. Exactly what relationships are we giving legal form? How do all the details work? In particular, a law shouldn’t create holes in the system, which would be easy to do. (If my health insurance plan covers my spouse, maybe I could establish universal health care by marrying everybody. Or maybe I could solve the immigration problem by marrying all of the undocumented immigrants. Yes, those examples are ridiculous. But it’s not hard to imagine more realistic unintended scenarios, where groups might redefine themselves as marriages to take advantage of a poorly phrased law.) deBoer argues that the difficult logistics of polygamy isn’t a reason not to do it. But a real proposal would have to deal with those logistics.

In short, I would tell both deBoer and Rauch the same thing: I’m convincible, but I’m not convinced. The anti-polygamy argument isn’t sharp enough, and the pro-polygamy argument isn’t detailed enough. But however the issue eventually comes out, it will do so on its own merits, and will not follow automatically just because gay couples or lesbian couples are getting married.

* I’ve questioned whether I should even use the word polygamy to cover all these possibilities, since it often refers specifically to Biblical polygamy, with polyandry referring to a woman with many husbands. But the articles I’ve referenced are comfortable with that usage, so I have reluctantly followed it.

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/2912048/Charlie_Hebdo_Mohammed_overwhelmed.0.png)