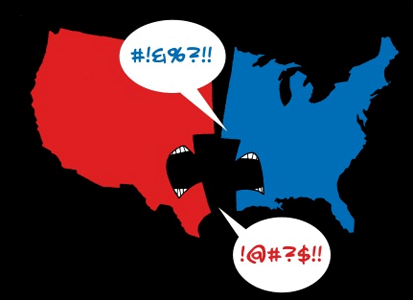

In a polarized world, it’s tempting and satisfying to think: My side is right and the other side is wrong. We represent truth, justice, and all that is good; they represent lies, corruption, and all that is evil. So the most direct way to improve the world is for Us to kick the crap out of Them.

As a liberal, though, I sometimes find it just as tempting (and satisfying in a different way) to think: No one has a monopoly on Truth; there are wise and good people on all sides. Democracy doesn’t work without compromise, and for any conflict there’s usually a higher Truth that transcends both poles. So it’s important for the wise and good people on all sides to stay in dialog and work towards understanding and consensus. Only then can we achieve the kind of win/win solutions that move humanity forward.

On one path, anger and self-righteousness provide energy and direction. On the other, identification with the yet-to-be-discovered wisdom of the future yields a softer (but perhaps more lasting) determination.

Each attitude (if I’m being really honest) offers its own kind of ego boost. In one, I’m superior to those stupid and corrupt conservatives; in the other I’m superior to everyone who hasn’t been to the mountaintop and seen my vision – or at least the vision that I plan to see when I get to the mountaintop.

In the blogosphere, kick-the-crap-out-of-them liberals and find-the-higher-truth liberals have their own polarization, which often manifests in bitter fights between idealists and pragmatists. So in this post, I’m doing what any good meta-liberal would do: I’m searching for the higher truth that transcends the conflict between crap-kicking liberals and conflict-transcending liberals.

The text for my sermon is Jonathan Haidt’s recent book The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion. Obviously, Haidt hails from the conflict-transcending tribe. He describes himself as a life-long liberal from academia, but living among the common people in India opened his eyes to the worthiness of conservative values like in-group loyalty and respect for authority, and the data he has collected since convinces him that there is wisdom on both sides.

Now if only all the wise and good people could transcend polarization and get into dialog.

Not so fast. If Haidt had completely convinced me, I would write a polemic about how conflict-transcending liberals need to kick the crap out of the crap-kicking liberals who poison the dialog that we otherwise could be having with wise and good conservatives.

But I also read Charles Blow’s post in February, showing that compromise itself is a liberal value conservatives don’t share. In poll after poll, Democrats say their leaders should compromise to get something done, while Republicans say their leaders should stick to conservative principles.

Given that difference, the path of least resistance is for Democrats to compromise and Republicans to move ever further to the right. So the Heritage Foundation’s conservative alternative to HillaryCare begets ObamaCare, which Heritage now denounces as an unconstitutional Marxist plot to take over the economy.

I sometimes imagine inviting the Ricks (Santorum and Warren) to a dialog aimed at finding a truth that transcends both my secularism and their Christianity. It’s a non-starter. To the Ricks, the very idea of a truth transcending Christianity is Satanic. Even liberal Christianity might be Satanic.

Worse, you can’t negotiate with Wisdom and Goodness when Lies and Corruption are in the driver’s seat. Think about climate change: The “controversy” over global warming comes not from the laboratories of dissident scientists, but from the board rooms of Exxon-Mobil and Koch Energy.

Corporations are sociopaths; they aren’t influenced by arguments about truth and goodness. So whatever evidence emerges, fossil-fuel companies (and their PR firms, lobbyists, and senators) will challenge the scientific consensus on global warming until they’ve sold the last trainload of coal to the last power plant to run the last air conditioner.

How do you find common ground with that? Don’t we just have to win?

Haidt’s case. Armored with appropriate skepticism, then, let’s look at what Haidt has to say.

Haidt has very artfully organized his book to illustrate his own principles. He believes people first react to an idea intuitively, and only then engage their rational minds to justify their reaction. So Haidt knows that if he turns people off on page 1, none of the evidence he offers later will get a fair hearing. So instead he engagingly tells the story of how he got to his conclusions while saving the conclusions themselves until the end.

He offers (and supports with data) a model of how this all-powerful moral intuition works: Humans have evolved to ‘taste’ six different moral ‘flavors’. Four are easy to describe:

- Care/harm. Don’t hurt the innocent, especially if they’re cute and helpless.

- Loyalty/betrayal. Don’t break your agreements or sabotage the team.

- Authority/subversion. Don’t get uppity and disrespect your betters.

- Sanctity/degradation. Don’t break your community’s fundamental taboos.

Haidt spells out the emotions these flavors evoke – violations of sanctity evoke disgust, for example, while violations of loyalty evoke rage – and how these responses (even the ones that contradict others) might have evolved.

Originally fairness was a fifth flavor, but eventually he realized that this word is used ambiguously for two different flavors.

- Liberty/oppression. Nobody is inherently better than anybody else. Example: Count each person’s vote equally.

- Fairness/cheating. Rewards should be proportional to contributions. Example: People who worker harder should make more money.

The punch line is that liberal moral arguments focus on Care and Liberty, while conservatives season their arguments with all six flavors. (Again, there’s supporting data.)

Politically, Haidt’s book has two big takeaways for liberals: (1) We should learn how to appeal to a wider palate. (2) Conservatives aren’t evil, they just taste different flavors of morality.

Not so fast, part II. I can buy (1), but I’ve got problems with (2). First, I taste those other flavors, I’m just deeply ambivalent about them, because I understand how they can serve evil purposes as easily as good: Being a team player and respecting authority can be bad (say, when you’re in Nazi Germany). Sanctity provides the ugh-factor that justifies oppression of out-groups like homosexuals. Distributing rewards proportionately to contributions can hide an unequal distribution of the opportunities to contribute.

I love a good strong salty taste, but it makes me worry about the value of what I’m eating.

Second, go back to my Exxon-Mobil example: Corporations don’t taste any flavors of morality, they just know how to manipulate the people who do. Fry up some pink slime, add a bunch of salt, and it tastes great!

Second, go back to my Exxon-Mobil example: Corporations don’t taste any flavors of morality, they just know how to manipulate the people who do. Fry up some pink slime, add a bunch of salt, and it tastes great!

How understanding do I want to be? But now I’m leaning too far over in the crap-kicking direction. I promised some transcendence. So here’s how much of Haidt I take to heart:

First, liberals need to distinguish what we’re fighting for from who we’re fighting with.

That dittohead friend from high school or the cousin who forwards right-wing viral emails – you probably already realize that they’re not bad people. If you can stand to talk politics at all with them, Haidt has a lot to tell you: You’re never going to convince them by yelling your liberal values back at them. To be convincing, you need to understand what flavor of morality they find in the positions they’re taking, echo that value to the extent you honestly can, and then detach it from the case at hand while you add liberal flavors to the stew.

But lies are poison, no matter how they’re flavored. You can cut some slack for the woman in the next cubicle who tells you Obama is a Kenyan. But you can’t cut any slack for the lie itself. “Why do you believe that?” invites dialog, but “You might be right” just surrenders.

And that TV-talking-head that a Koch-Brothers astroturf group pays to lie for them? He’s evil. Don’t waste your compassion trying to understand anything deeper about him than his paycheck.

Compromise on proposals, not principles. There’s nothing wrong with supporting the best proposal you can pass, even if the other side also manages to get some of its agenda in as well. That’s how democracy works.

For example, the 15th Amendment guaranteed black men the right to vote. Some feminists opposed it, because it should have given women the right to vote as well.

In principle, they were right: It should have. But I’m glad the 15th Amendment passsed, especially since the 19th Amendment eventually followed.

But no post-Civil-War liberal should have said, “It’s good that the 15th Amendment doesn’t apply to women.” Pass as much as you can, but never surrender your intention to come back for more.

Liberal/conservative isn’t symmetric. Haidt is right that six-flavor conservatism has an inherent advantage over two-flavor liberalism. We just don’t have as many ways to provoke a knee-jerk response. That’s why conservatism corrolates with low-effort thought.

That’s also why we can’t just invert the knee-jerk arguments of the right. The correct response to “Black people are bad” isn’t “White people are bad.” “America is always right” shouldn’t lead to “America is always wrong.”

Our side needs nuance. We need to engage thought rather than shut it down.

In particular, we need nuance when we respond to books like The Righteous Mind. The proper response to “Conservatives are good people” isn’t “Conservatives are bad people.” It’s “In what cases and what ways are conservatives good, and how can we engage them there without betraying our own values?”

When extremists have been shouting — and sometimes shooting — at each other for generations, the center is a hard position to hold. Each side has its own version of history, which begins with its own people minding their own business and being horribly victimized by the other side. Each side has its own framing of law and justice and human rights, in which it has always been right and the other side has always been wrong. Even the horrible things that are undeniable — the killing of innocents, the torture of helpless prisoners — were only done to prevent (or in reprisal for) something worse perpetrated by the other side.

When extremists have been shouting — and sometimes shooting — at each other for generations, the center is a hard position to hold. Each side has its own version of history, which begins with its own people minding their own business and being horribly victimized by the other side. Each side has its own framing of law and justice and human rights, in which it has always been right and the other side has always been wrong. Even the horrible things that are undeniable — the killing of innocents, the torture of helpless prisoners — were only done to prevent (or in reprisal for) something worse perpetrated by the other side.