Tim Alberta indicts the religion he grew up in, but ends on a hopeful note. How convincing is that?

In the news sources I follow, Tim Alberta and his new book The Kingdom, the Power, and the Glory: American Evangelicals in an age of extremism have been everywhere lately. As of yesterday, it was the #1 best seller in Amazon’s “Christian Church history” category. The book’s web page boosts it as a “New York Times Bestseller, one of Barack Obama’s Favorite Books of the Year, and an Air Mail best book of the year.” An excerpt — the book’s prologue, in which Alberta reminisces about his Evangelical-preacher father and describes how his father’s flock assailed Alberta for his politics when he returned to the megachurch his father founded for his father’s funeral — has appeared in The Atlantic. He’s been interviewed on numerous MSNBC shows, including The 11th Hour. Michelle Goldberg wrote a column about his book, though I can’t find any clue that she read all the way to the end.

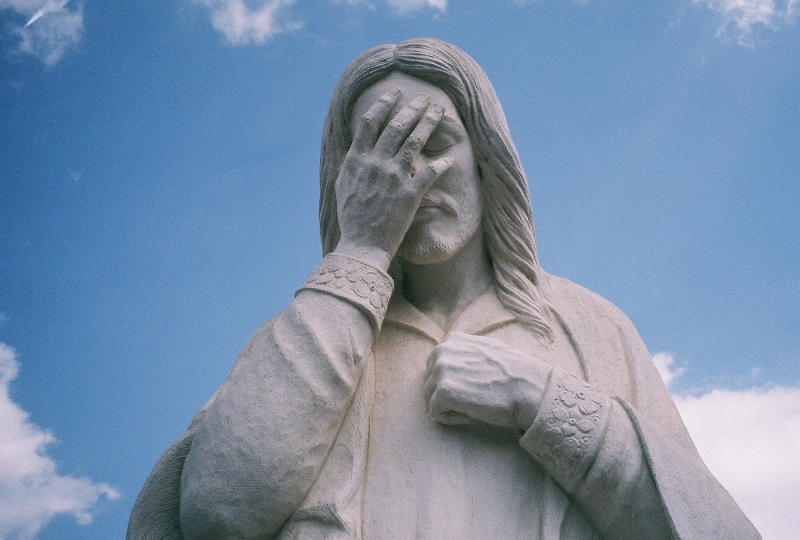

So chances are you’ve heard about Alberta, and maybe you know the thesis of his book: He surveys how right-wing politics has taken over the Evangelical movement, which today is often more about Trump than about Jesus, and whose Promised Land is not Heaven, but an America re-dominated by Christian leaders (who are probably White, male, and Republican, and definitely straight). Christianity, whose “kingdom is not of this world“, has been corrupted by a very worldly American nationalism.

What is special about Alberta’s perspective is that he critiques Evangelicalism from the inside. The fundamental problem he sees in Christian Nationalism isn’t that it violates the Constitution or opposes democracy or goes down the rabbit holes of absurd conspiracy theories, but that it is a heresy. Worshiping America (or Trump) is a form of idolatry. Jesus, in Alberta’s view, would have us change the world by channeling God’s love, not by promoting an angry, fearful, hateful brand of politics. God is eternal, and He cares little about nations, which come and go. (Galatians 3:28 says “There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither bond nor free, there is neither male nor female: for ye are all one in Christ Jesus.”)

Access. Alberta’s book demonstrates a level of access that I find hard to imagine. Some of the most famous — and most outrageous — characters in American Christianity sit down with him and share their unguarded (or barely guarded) thoughts.

- Robert Jeffress (the Dallas megachurch pastor who was key in bringing Evangelicals to Trump in 2016 and in defending his worst excesses) discussed his post-1/6 doubts about how far he went to promote Trump. “I had that internal conversation with myself — and with God, too — about, you know, when do you cross the line? When does the mission get compromised?” Alberta pushed on that a little and Jeffress confessed, “I think it can be [compromised]. I think it even was, these last few years.” (Jeffress is back in the Trump fold now.)

- Greg Locke, the Tennessee preacher whose church mushroomed when he defied public-health restrictions to stay open during the pandemic, and instead turned his church into a center of anti-vax, anti-liberal, and anti-government conspiracy theories, tells Alberta, “I’ve grown. … Are there times that it’s been perceived that I cared more about the kingdom of earth than the kingdom of heaven? Probably. And that was probably my fault. I probably shot myself in the foot and got a little too animated about things.” (Maybe he meant it.)

- On election day 2022, Alberta had breakfast with the Christian Coalition founder Ralph Reed, who predicted a big night for Senate candidate Herschel Walker.

- He reports numerous conversations with Russell Moore, a central character in the right/left struggles of the Southern Baptist Convention. And with Jerry Falwell Jr., who was pushed out as president of Liberty University under a cloud of scandal.

It goes on like that. List everybody you wish you could talk to about these issues, and Alberta talked to them. They appear to have taken his questions seriously rather than stiff-arming him as part of the liberal media. People who usually take a double-down, show-no-weakness attitude towards probing questions seem to have wanted Alberta to understand them and their points of view.

What point of view? Because we so seldom get our questions answered, people like me have a hard time piecing together how Evangelicals look at themselves and come to their (to me) bizarre-looking political positions. As best I can piece it together now, the logical order goes like this: Over the last 50 years or so, American culture has either de-emphasized or outright rejected many conservative Christian ideas about morality. So now abortion, homosexuality, interracial marriage, same-sex marriage, pre- and extra-marital sex, and even (in some communities) transsexuality are all OK. Evangelicals see this creep of standards as moving primarily against them, rather than in favor of previously oppressed groups like, say, gays. So they extrapolate forward to a society where they will be persecuted the way the early Christians were by Rome. When churches were closed during the pandemic — along with theaters, sporting events, and any other place where crowds typically assemble — they took it personally, as the first act of a liberal Deep State that is eager to shut them down.

This interpretation and this fear looks paranoid to me. (After all, I’m pretty liberal and I never run into anybody who is eager to shut down churches permanently and persecute their members. The suggestion just never comes up.) So I have no idea who in particular they should be afraid of. But it’s very real to them, which is why many of them have a we-are-facing-the-apocalypse mindset. Preachers and politicians have promoted this fear, preyed on it, and taken advantage of it. The result is a sense of desperation, a willingness to believe ridiculous conspiracy theories, and an eagerness approve some very un-Christ-like tactics.

That result looks to Alberta like a profound loss of faith in the message of Jesus, who said “Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, that you may be children of your Father in heaven.” Instead, Evangelicals find themselves looking for someone more badass than Jesus, which is what they like about Trump.

Structure. Alberta’s book is made up of three parts: The Kingdom is his tour of Evangelical churches, where he talks to the Trumpiest pastors he can find, as well as to pastors who are struggling not to lose their churches to this Christian Nationalist movement. One such church is Cornerstone Evangelical Presbyterian Church in Brighton, Michigan, which was founded by Alberta’s father and is where Tim grew up. In Chapter 1 we meet his father’s hand-picked successor, Chris Winans, who isn’t willing to endorse right-wing politics from the pulpit, and so is watching his membership plummet. But in Chapter 7 we meet Bill Bolin, whose Floodgate church in the same town is riding the right-wing wave — stolen election, vaccine horror stories, looming Christian persecution — to grow and prosper.

Part II, The Power, focuses on politicians and political operatives who are harnessing Christian Nationalism, people like the fake historian David Barton, Ralph Reed, and Charlie Kirk of Turning Point USA. Alberta attends a session of Michael Flynn’s ReAwaken America tour, which is like a tent revival for QAnon types. But he also talks to an apostate of the religion-meets-rightwing-politics movement: Cal Thomas, who anticipated much of what ultimately went wrong in his 1999 book Blinded By Might.

Part III, The Glory, is the hopeful part of the book, which I found unconvincing. He focuses on people who have survived the right-wing wave, including a return to Winans at Cornerstone, who over a period of years has rebuilt the church’s membership while keeping his message Christian rather than nationalist. Activists who want the Southern Baptist Convention to address its sex-abuse issue win a vote, and then beat back a right-wing counterrevolution. Jerry Falwell Jr. gets ousted at Liberty University, and is replaced by people who maybe maybe will start to take LU’s stated mission seriously. Stuff like that.

In the final chapter, one of the book’s sympathetic characters, LU Professor Nick Olson, delivers this optimistic vision of a revitalized Christian church:

I think the first step is reimagining the Christian worldview. And that means replacing our dominant metaphor — culture war — with something different. That’s been the running theme for evangelicals: we’re always embattled, always fighting back. But what if we laid down our defense mechanisms? What if we reframed our relationship to creation, to our neighbors, to our enemies, in ways that are more closely aligned to the Sermon on the Mount? What if we were willing to lay down our power and our status to love others, even if that comes at cost to ourselves?

Good luck with that, Nick. It’s a beautiful thought, but the currents still seem to me to be running in the other direction.

My response. In his hopeful Part III, I think Alberta underestimates how deep the structural problems in Christianity run, a case I made in a 2022 post “How did Christianity become so toxic?“.

In my experience, the style of motivated reasoning we see in the Trumpist movement (where, for example, Bill Clinton’s sexual excesses were disqualifying, but Donald Trump’s as-bad-or-worse actions are just part of his charm) began a long time ago. The willingness of Christians to deny facts, to seize on any useful misrepresentation, and to apply more favorable standards to people on their own side — I was running into this back in the 70s when fundamentalists argued against evolution, and probably it had been going on for decades before that.

Over time, anti-evolution became a template for denying anything conservative Christians didn’t want to believe: global warming, the effectiveness of vaccines, anything. The nonsense put out by the anti-abortion movement — that six-week-old fetuses have a heartbeat, 15-week fetuses feel pain, abortion can cause breast cancer, and so on — is unkillable, because conservative Christians live in a world where facts and science don’t matter. If some argument advances your position, then it must be true. Standing against this kind of nonsense means that you have turned against your faith.

Any serious attempt to clean this all up and teach sound reasoning will cost Evangelicals things they value far more than the truth. They’ll have to admit that the Earth has been around far longer than a few thousand years, that the diversity of human languages must have started much earlier than the Tower of Babel, that there never was a worldwide flood, and so on. They’ll have to account for obvious contradictions in the Bible. (The clearest, I think, is between the two genealogies of Jesus in Matthew and Luke. It’s not just a matter of the names being different; they don’t have the same number of generations between David and Jesus.)

They won’t have to give up on the teachings of Jesus, but they’ll be left with a faith far more complicated than “that old time religion” they want to believe in.

Above all else, Evangelicals believe the things they want to believe. So it’s not going to happen — which means that even if the Trumpist heresy ultimately fails, there will soon be another one, because the tools to build one are so widely distributed and easy to use.

And then there’s the propensity to invent paranoid conspiracy theories. This is baked into the theology at a very deep level: There is a Devil, who represents ultimate evil and has human minions to work his will.

When rational people confront a conspiracy theory, the unraveling usually begins with one question: Who would do all this and why? But Evangelical theology provides a ready-made answer: The Devil and his minions would do this because they’re evil. The diverse pieces of the conspiracy may have no apparent contact with each other, but they share inspiration from a being not of this world. If in addition you allow them occasional acts of supernatural power, then there’s no conspiracy you can’t rationalize.

The paranoid part comes from the fact that Devil’s primary goal is to destroy the One True Church and persecute its followers. You may belong to the biggest, richest, most powerful religion on the planet, and your pastor may meet regularly with the President of the United States, but it doesn’t matter. Some powerful entity is trying to persecute you, and you will never be safe from him.

This is not to say that all Evangelicals are necessarily paranoid and captured by false narratives that they cannot examine rationally. But the DNA of their faith makes them vulnerable to paranoia and false narratives. If they understood that fact, they could guard against those traps and call each other back when they fall down those rabbit holes. But the vulnerability that their faith builds into their thinking processes is the very first thing they are driven to deny.

POSTSCRIPT

After reading the comments, I feel like I should post some general remarks about my attitude toward religion.

I am not, in general, against religion. I belong to a church myself, albeit a Unitarian Universalist church, which some people would say is not really a religion. (I disagree.)

There are obvious social advantages in belonging to a church: In our atomized society, we usually only meet people in specific roles, and it’s hard to form the kind of relationships where the whole of my life is involved in the whole of somebody else’s life. In a church, you not only meet a person, you may also meet the person’s spouse, kids, possibly parents, and some of their friends. Deeper conversations about what we’re each trying to do with our lives and what’s stopping us from doing it — they don’t violate our roles, the way they might in another setting.

But beyond the social, a weekly church service is a way to regularly remind myself, and for a community of people to remind each other, that we want to be better than this. Overall American culture places such importance on money, status, fame, career success, and so on. It can be hard to remember that life should be about more than that.

At its best, religion can posit what a better world looks like: a place where everyone is treated with respect, where people care about each other too much to let them fall through society’s cracks, where we aspire to find truth and beauty, and where everyone has a chance to become their best self. It’s valuable to know that this vision is not just some crazy idea I dreamed up, but that a community of people shares it.

So far I haven’t said anything about God, because traditional notions of God don’t play a big role in my thinking. I sometimes describe myself as a “functional atheist”. If you have a vision of God that is meaningful for you and helps you be a better person, I won’t try to talk you out of it. I may even use your God-language in our conversations, if it helps get an idea across. But “this is what God wants me to do” usually doesn’t come up when I’m trying to make decisions in my own life.

That said, I have an appreciation of even theistic religion. If a religious community has its vision of a better world right (or even close to right), the idea that God wants this for us can be powerful. If a religion motivates its believers to do the hard work of improving the world, I’m not eager to change their minds.

Now, obviously, a lot of religion isn’t like that. Communities of people can get together each week to justify being their worst selves, or to share a vision of a world where large parts of humanity are made to suffer. I’m not defending that. I just don’t think that religion necessarily has to turn out that way.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/58388775/619309888.jpg.0.jpg)