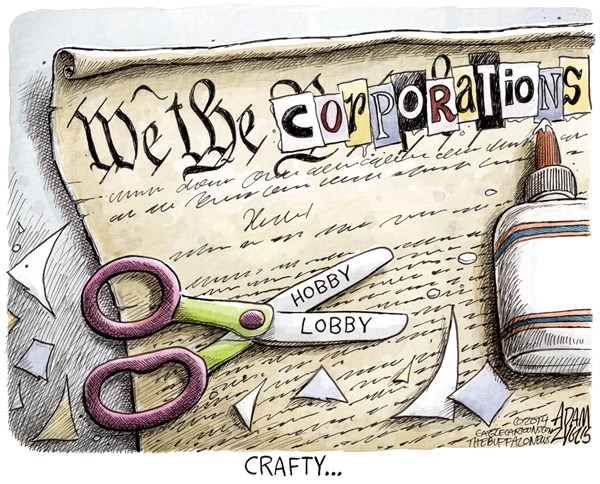

The Court’s five male Catholic justices outvoted its three Jews and lone female Catholic. Is that a problem?

It is easy to be confused by the commentary on the Supreme Court’s 5-4 ruling that Hobby Lobby and Conestoga are exempt from the contraception mandate of the Affordable Care Act. The ruling, say some, is narrow; it will affect only a handful of business-owners in a more-or-less identical situation, and their female workers’ coverage will not suffer. No, say others, the consequences of the ruling are sweeping; it puts all workers’ health coverage at the mercy of whatever religions their employers’ corporations decide to adopt, and could have further consequences unrelated to healthcare.

Each of those views is right in its way. Justice Alito’s majority opinion emphasizes its limitations; cases that seem analogous, he says several times, may turn out differently. An important point in Alito’s argument is that the government might easily achieve its purpose — covering contraceptive care for women whose employers have religious objections — by pushing the small expense of the coverage back on the insurance companies, as it already does for some religious organizations like churches, hospitals, and colleges. Such a simple fix is probably unavailable if companies object to covering vaccines or blood transfusions, much less seeking exemptions from civil rights laws.

But Justice Ginsburg was not comforted by Alito’s assurances of what may or might happen. Analogous cases may turn out differently, but they might not. Countless numbers of them will work their way through the system for years to come, creating unnecessary chaos as lower courts explore the consequences of Alito’s new interpretations of religious liberty and corporate law.

And who knows? The Court has committed itself to nothing, so maybe those cases will lead to new sweeping rulings by the Court’s increasingly activist conservative (and male Catholic) majority. The government’s “easy” fix to the contraception mandate is itself challenged in a case that the Court will probably hear next year; immediately after the Hobby Lobby ruling, the Court issued an emergency order demonstrating that it takes that case seriously.

What does the ruling say? Here’s the full opinion of the Court — Alito’s 49-page ruling and Ginsburg’s 35-page dissent, plus a few paragraphs from other justices. Law professor Eugene Volokh summarized Alito’s ruling in 900 words, and Ezra Klein got it down to three sentences:

-

A federal law called the Religious Freedom Restoration Act was written to protect individuals’ religious freedoms — and on Thursday, the Supreme Court ruled that, under RFRA, corporations count as people: their religious freedoms also get protection.

-

The requirement to cover contraception violated RFRA because it mandated that businesses “engage in conduct that seriously violates their sincere religious belief that life begins at conception.”

-

If the federal government wanted to increase access to birth control — which they argued was the point of this requirement — the Court thinks it could do it in ways that didn’t violate religious freedom, like taking on the task of distributing contraceptives itself.

Alito clearly thinks (or wants us to think) that his ruling is narrowly targeted:

This decision concerns only the contraceptive mandate and should not be understood to hold that all insurance-coverage mandates, e.g., for vaccinations or blood transfusions, must necessarily fall if they conflict with an employer’s religious beliefs. Nor does it provide a shield for employers who might cloak illegal discrimination as a religious practice.

But Ginsburg’s dissent begins:

In a decision of startling breadth, the Court holds that commercial enterprises, including corporations, along with partnerships and sole proprietorships, can opt out of any law (saving only tax laws) they judge incompatible with their sincerely held religious beliefs.

And later she explains:

Although the Court attempts to cabin its language to closely held corporations, its logic extends to corporations of any size, public or private. Little doubt that RFRA claims will proliferate, for the Court’s expansive notion of corporate personhood—combined with its other errors in construing RFRA—invites for-profit entities to seek religion-based exemptions from regulations they deem offensive to their faith.

Ginsburg sees four dangerous new principles in Alito’s ruling:

- Originally, the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993 was meant to restore an interpretation of the First Amendment’s free-exercise clause that the Supreme Court backed away from in 1990. Alito has cut the RFRA loose from history of First Amendment interpretation, giving future Courts broad license to expand the notion of religious liberty.

- Alito has granted RFRA rights to for-profit corporations, extending the legal fiction of corporate personhood into a previously unexplored realm, and blowing away the long-observed distinction between for-profit corporations and specifically religious organizations (like churches) created to serve their members.

- The meaning of a “substantial burden” on religious liberty has been significantly weakened and made subjective.

- The “corporate veil” — the legal separation between corporations and their shareholders — has been turned into a one-way gate. The rights of the shareholders now flow through to the corporation, but the debts, crimes, and responsibilities of the corporation still don’t flow back to the shareholders.

Let’s take those one by one.

The RFRA goes beyond any previous history of First Amendment interpretation.

For decades, the Court applied what it called the Sherbert test to First Amendment, religious-liberty-infringement cases: A law could require a person to violate his/her religion — say, by working on the Sabbath — only if the law was the least restrictive way to achieve a compelling government interest. But in 1990 it backed away from that principle in the Smith decision: If a law had a larger purpose and didn’t specifically target a religion, it didn’t have to be quite so accommodating.

Congress then passed the Religious Freedom Restoration Act to reinstate the Sherbert Test by statute. That’s what the law says and that’s how it has been interpreted. But you can’t justify the Hobby Lobby decision from the pre-Smith precedents, because you run into the 1982 Lee decision, concerning whether an Amish employer had to pay Social Security taxes:

Congress and the courts have been sensitive to the needs flowing from the Free Exercise Clause, but every person cannot be shielded from all the burdens incident to exercising every aspect of the right to practice religious beliefs. When followers of a particular sect enter into commercial activity as a matter of choice, the limits they accept on their own conduct as a matter of conscience and faith are not to be superimposed on the statutory schemes which are binding on others in that activity. Granting an exemption from social security taxes to an employer operates to impose the employer’s religious faith on the employees.

Alito doesn’t answer Lee, he just blows it away:

By enacting RFRA, Congress went far beyond what this Court has held is constitutionally required.

In other words, in spite of its name the RFRA doesn’t “restore” anything; it’s a revolutionary assertion of new religious rights unrelated to the First Amendment. How far do those new rights go? Alito doesn’t say. A more detailed analysis of this issue is in Slate. Daily Kos’ Armando has an interesting response: If the RFRA really does mean what Alito claims, then the RFRA itself is an unconstitutional establishment of religion.

The RFRA extends to for-profit corporations.

The RFRA uses the word person and doesn’t define it, so Alito argues that the definition must come from the Dictionary Act of 1871, which says

The RFRA uses the word person and doesn’t define it, so Alito argues that the definition must come from the Dictionary Act of 1871, which says

the words ‘person’ and ‘whoever’ include corporations, companies, associations, firms, partnerships, societies, and joint stock companies, as well as individuals.

(If the Dictionary Act rings a bell in your head, here’s where you’ve heard of it before: The way the Defense of Marriage Act affected thousands of laws in one swoop was by amending the Dictionary Act’s definition of marriage.) But Ginsburg points out that the Dictionary Act “controls only where context does not indicate otherwise.” Since “the exercise of religion is characteristic of natural persons, not artificial legal entities” the context of a law concerning the exercise of religion already excludes corporations.

Alito wants to claim his ruling only applies to “closely-held corporations”, but that’s not what the Dictionary Act says. If Bank of America wants to admit that it worships Mammon — a religion at least as old and popular as Christianity — it can claim free-exercise rights.

Alito’s reasoning has already had one very unintended consequence: A Guantanamo detainee was previously denied protection of the RFRA, because a court decided that the meaning of “person” in his case was not the Dictionary Act definition. Now that the Supreme Court has gone on record saying the “person” in the RFRA has the Dictionary Act meaning, he is claiming his case should be re-considered.

The meaning of “substantial burden” was weakened.

ObamaCare didn’t require the owners of Hobby Lobby to use, manufacture, distribute, or even necessarily buy contraceptives. They were merely required to provide health insurance that would cover contraceptives if the employees decided to use them. If Hobby Lobby employees agreed with the owners’ scruples, no violation of those scruples would take place.

Ginsburg did not find this burden “substantial”.

It is doubtful that Congress, when it specified that burdens must be “substantial,” had in mind a linkage thus interrupted by independent decisionmakers (the woman and her health counselor) standing between the challenged government action and the religious exercise claimed to be infringed.

But Alito did:

The belief of the Hahns and Greens implicates a difficult and important question of religion and moral philosophy, namely, the circumstances under which it is immoral for a person to perform an act that is innocent in itself but that has the effect of enabling or facilitating the commission of an immoral act by another. It is not for the Court to say that the religious beliefs of the plaintiffs are mistaken or unreasonable.

But surely any clever person can find a link of some sort between whatever they don’t want to do and the commission of some act they consider immoral by someone else. Alito is encouraging Christians to develop hyper-sensitive consciences that will then allow them to control or mistreat others in the name of religious liberty, a pattern I described last summer in “Religious ‘Freedom’ Means Christian Passive-Aggressive Domination“.

I focus on Christians here for a very good reason: Given that this principle will produce complete anarchy if generally applied, it won’t be generally applied. Contrary to Alito’s assertion, judges will have to decide whether the chains of moral logic people assert are reasonable or not. For example, elsewhere in his opinion he brushes off the objection that corporations will claim religious benefits to increase their profits:

To qualify for RFRA’s protection, an asserted belief must be “sincere”; a corporation’s pretextual assertion of a religious belief in order to obtain an exemption for financial reasons would fail.

But how would it fail, if “it is not for the Court to say” whether asserted religious beliefs are unreasonable? If Randism is repackaged as a free-market-worshipping religion, won’t any regulation infringe on it? Who could claim that Koch Industries is “insincere” in its Randism?

In practice, a belief will seem reasonable if a judge agrees with it. That’s what happened in this case: Five male Catholic judges ruled that Catholic moral principles trump women’s rights. Three Jews and a female Catholic disagreed.

The nature of corporations was re-imagined.

The nature of corporations was re-imagined.

Ginsburg:

By incorporating a business, however, an individual separates herself from the entity and escapes personal responsibility for the entity’s obligations. One might ask why the separation should hold only when it serves the interest of those who control the corporation.

Alito brushes away this separateness:

A corporation is simply a form of organization used by human beings to achieve desired ends. An established body of law specifies the rights and obligations of the people (including shareholders, officers, and employees) who are associated with a corporation in one way or another. When rights, whether constitutional or statutory, are extended to corporations, the purpose is to protect the rights of these people.

Alito waves his hand at employees, but his ruling only applies to owners, i.e., rich people. So in Alito’s reading of corporate law, corporations protect rich people’s rights while shielding them from responsibilities. It is a way to write inequality into the law.

A friend-of-the-court brief written by “forty-four law professors whose research and teaching focus primarily on corporate and securities law and criminal law as applied to corporations” says Alito’s “established body of law” doesn’t work the way he says, and that making it work that way will open “a Pandora’s box”.

The first principle of corporate law is that for-profit corporations are entities that possess legal interests and a legal identity of their own—one separate and distinct from their shareholders. … [T]he most compelling reasons for a small business to incorporate is so that its shareholders can acquire the protection of the corporate veil. … Allowing a corporation, through either shareholder vote or board resolution, to take on and assert the religious beliefs of its shareholders in order to avoid having to comply with a generally-applicable law with a secular purpose is fundamentally at odds with the entire concept of incorporation. Creating such an unprecedented and idiosyncratic tear in the corporate veil would also carry with it unintended consequences, many of which are not easily foreseen.

The brief spells out some of the foreseeable consequences: battles between shareholders (perhaps spilling into court) about a corporation’s religious identity, weakening of the shareholders’ shielding against the debts and/or crimes of the corporation, corporations whose religious identities exempt them from certain laws might obtain advantages over their competitors, minority shareholders might sue a management that refused to take on an advantageous religious identity (because it failed to maximize profit), and many more. They conclude:

Rather than open up such a Pandora’s box, the Court should simply follow well-established principles of corporate law and hold that a corporation cannot, through the expedient of a shareholder vote or a board resolution, take on the religious identity of its shareholders.

Conclusion: The Box is Open.

More cases are already in the pipeline, cases that object to all forms of contraception, not just the four Hobby Lobby’s owners view as abortion-causing. One objects to paying for “related education and counseling”, so even seeing your doctor to discuss contraceptive options might be out. Religious employers are already asking to be exempt from rules about hiring gays and lesbians. Photographers and bakers want to be free to reject same-sex marriage clients. Beyond that, who can say what plans are being hatched in religious-right think tanks or corporate law offices?

The Court did not endorse these claims in advance, but it laid out sweeping new principles and did not provide any tests to limit them.

Comments

The Affordable Car Act? I LOL’d.

I wish I’d read your comment sooner. Fixed now. Thanks.

Darn! Next time, Affordable Cat Act. 😉

The 19th century version of the Affordable Car Act was the Affordable Mare Act.

#Lobbyhobby: I always understood that corporate entities exist at the pleasure of the State. And WE are ALL The State.

Why can’t corporations have beliefs? They have mission statements, core values, etc. These are reflections of the business ethics and morality of the corporation. BOTTOM LINE: if you don’t like it then DON’T. WORK. THERE.

Assuming you have a choice.

The larger question isn’t whether corporations can have core values written into their mission statements, but whether those values deserve the protection that the Constitution and the RFRA give to the consciences of real people.

Trackbacks

[…] This week’s featured article: “How Threatening Is the Hobby Lobby Decision?“ […]

[…] — it is, but the Supreme Court has five conservative judges who might be happy to issue another bogus partisan ruling against ObamaCare — but because the stock price of health insurance companies didn’t budge when the D. C. […]

[…] year I explained the Supreme Court’s Hobby Lobby decision, the Schuette decision about affirmative action, and the McCutcheon decision on campaign […]

[…] included the ability to build a house of worship.) Justice Alito’s majority opinion in the Hobby Lobby case more-or-less just laughed off the idea that employers with less mainstream religious views — […]

[…] opinion at the Supreme Court. I discussed what’s wrong with Alito’s decision in “How Threatening is the Hobby Lobby Decision?” But the more general piece I want to call attention to is the earlier “Religious […]

[…] That’s why I’ve never been moved by the plight of conservative Christian pharmacists forced to provide contraception they disapprove of, or Christian florists who get sued for discriminating against same-sex couples, or Christian employers whose workers might use their health insurance in ways forbidden by the employer…. […]

[…] I felt the same way about the Supreme Court’s Hobby Lobby decision. […]

[…] might try to force me to sell a gay couple the same cake I would sell a straight couple! Or to provide health insurance for my employees! It’s just exactly like the stoning of Stephen, or facing the lions in […]

[…] that simple clarity doesn’t mean that the Supreme Court will see it that way, because the Hobby Lobby case was also an easy call under the law: The owners had a legal responsibility to offer health insurance, and what the employees chose to […]

[…] Trump’s ban on accepting visitors or immigrants from certain Muslim-majority countries deserves the benefit of the Court’s doubt, and should not be interpreted in light of the unconstitutional Muslim Ban he campaigned on and sought to implement in two previous executive orders. Neither should the Court examine too closely the flimsy national-security justifications the administration offers. Justice Sotomayor’s dissent reviews Trump’s anti-Islam statements both before and after taking office, and concludes: “In sum, none of the features of the Proclamation highlighted by the majority supports the Government’s claim that the Proclamation is genuinely and primarily rooted in a legitimate national-security interest. What the unrebutted evidence actually shows is that a reasonable observer would conclude, quite easily, that the primary purpose and function of the Proclamation is to disfavor Islam by banning Muslims from entering our country.” She contrasts the Court’s unwillingness to consider Trump’s anti-Islam statements with the seriousness it ascribed to Colorado officials’ lack of respect for the baker’s Christian beliefs in the Masterpiece Cakeshop case. But those were Christians and these are Muslims. As I have pointed out many times in the past, this Court grants Christians special rights. […]

[…] You may find it bizarre that Obama, who (unlike Trump) was scrupulously polite to his opponents, is seen as “the bully”. As best I can tell, liberal “bullying” consists mostly of recognizing same-sex marriage, enforcing anti-discrimination laws, and requiring Christian businesses to offer their employees a full range of healthcare benefits. […]

[…] Hobby Lobby, where the Supreme Court ruled that an employer’s Christian beliefs trump the right of employees to make their own healthcare choices. […]

[…] is a very simple principle that would avoid all these cases (including the horribly-decided Hobby Lobby case): What employees do with their health insurance is not the employer’s business. The Little […]