The great tactical disadvantage for all those of us who will fight for democracy is that you have one tool to do it: democracy. You must use democratic means to defeat anti-democratic forces. And that can feel like fighting with one hand tied behind your back. But you’re either a democrat or you’re not.

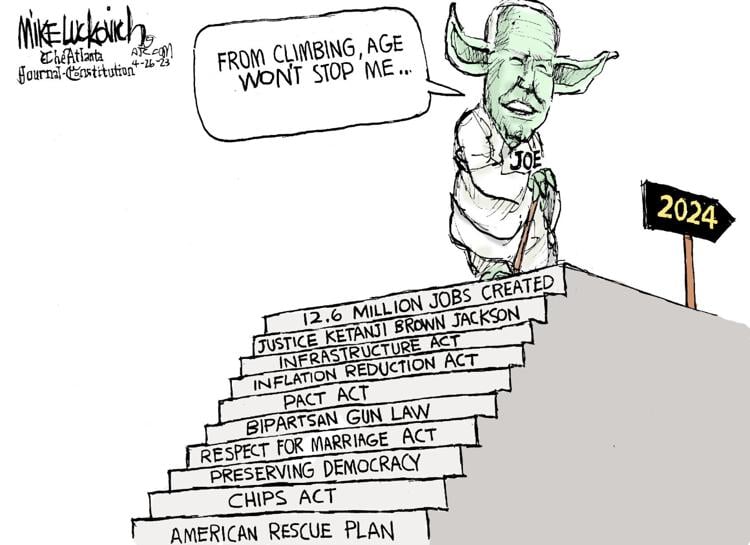

This week’s featured post is “The Remarkable Biden Economy“.

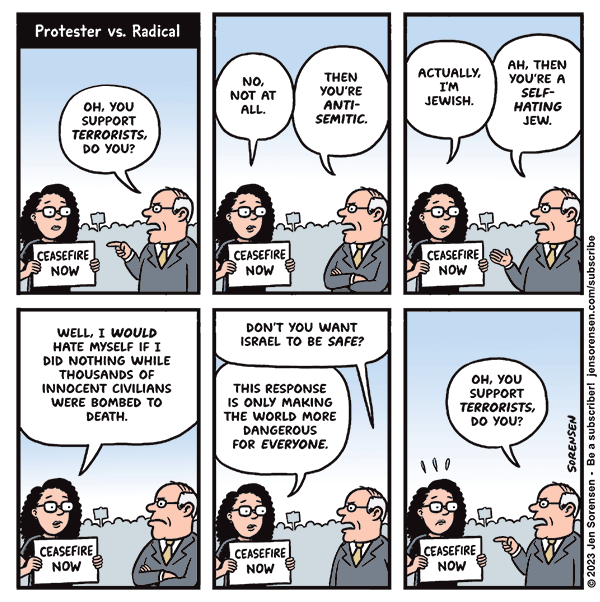

This week everybody was talking about the hostage release in Gaza

The long-rumored ceasefire-with-prisoner-exchange deal between Israel and Hamas took effect Friday. The ceasefire started then and was supposed to last four days. Talks are underway to extend that period and perhaps free more hostages. Otherwise, fighting will resume tomorrow.

Any agreement that results in real actions is a good sign: The two sides have ways to talk to each other, and are building trust that agreements made can be carried out. But there’s still a long, long way to go. (Late-breaking reports say the truce will last another two days.)

and the Dutch election

Anti-Islam and anti-EU politician Geert Wilders led his Party for Freedom to a surprisingly good showing in the parliamentary elections Wednesday. Still far from a majority, his 35 seats is the most by any individual party in the 150-seat parliament. He will get the first chance to put together a majority coalition.

I’m not sure the WaPo is correct in interpreting this result as showing a rising right-wing momentum in Europe, especially given the Polish election results in October. But it bears watching.

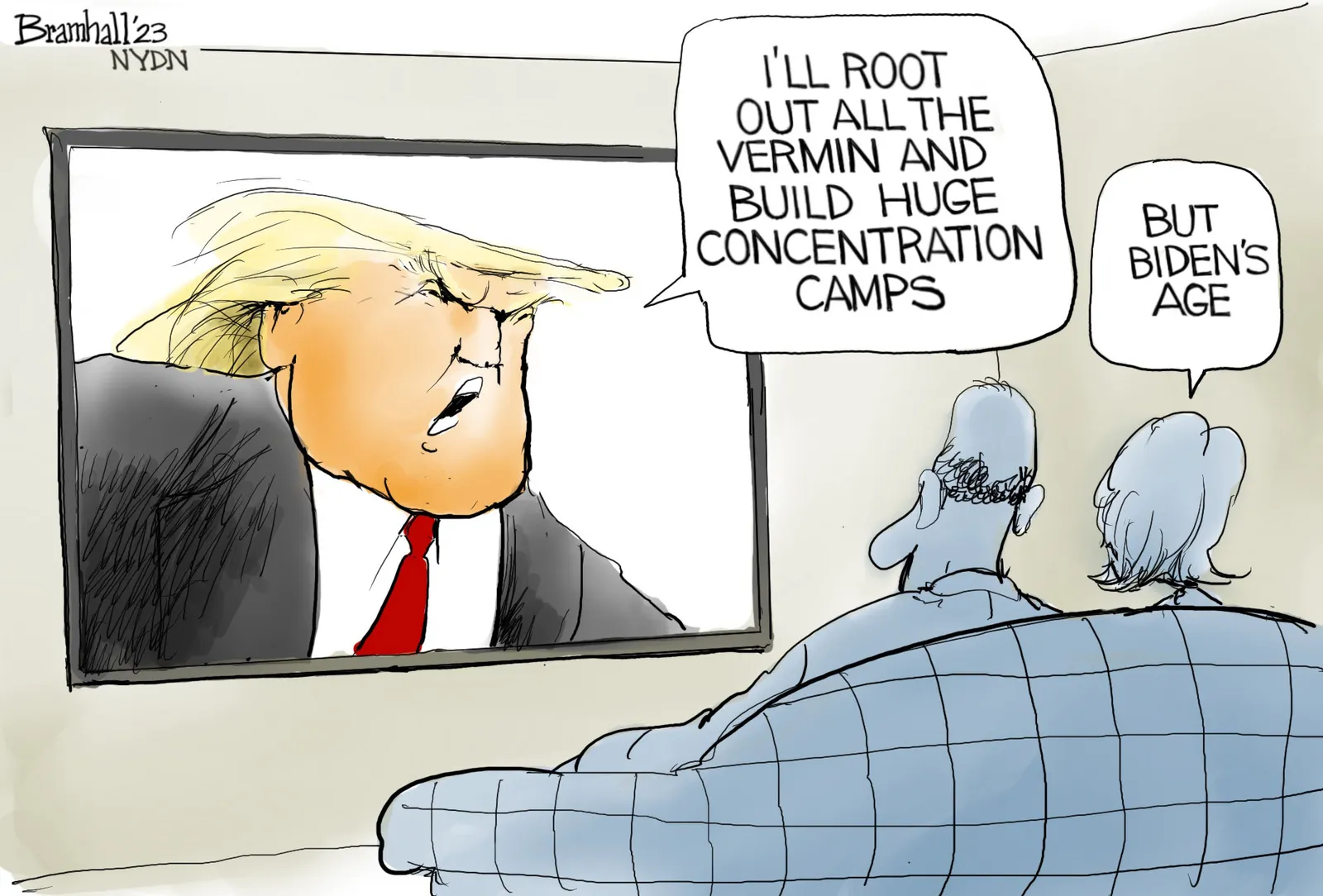

but we should talk more about how Trump gets covered

Major media still seems to be having a hard time figuring out how to cover Trump. In 2015, he was a man-bites-dog story who clearly was never going to be president anyway, so he got millions and millions of dollars worth of free media coverage. Entire Trump speeches were broadcast live on CNN, and quotes the media determined to be “gaffes” got repeated again and again.

Eventually, outlets noticed that they had become vehicles for disinformation. Unlike the typical presidential candidate, Trump was not embarrassed to be caught in a lie, and would keep repeating the lie long after fact-checkers had debunked it. In fact, he had more persistence than the fact-checkers, so he would keep lying, while fact-checkers found it pointless to keep repeating the same debunking columns. This led WaPo’s Glenn Kessler to invent the “bottomless Pinocchio”:

The bar for the Bottomless Pinocchio is high: The claims must have received three or four Pinocchios from The Fact Checker, and they must have been repeated at least 20 times. Twenty is a sufficiently robust number that there can be no question the politician is aware that his or her facts are wrong.

Similarly, Trump’s “gaffes” were not the usual sort of political misstatements: slips of the tongue or half-truths that got stretched to the point of hyperbole, like Hillary Clinton’s harrowing tale of landing in Bosnia under sniper fire. Trump wasn’t misspeaking, he was intentionally trolling; he said outrageous things strategically, to get attention and change the direction of the national conversation. (You can see that happening now with his trials. Are the news headlines about the damning and unanswerable evidence of his criminality? Of course not. They’re about some attack on a court official or witness or prosecutor that is likely to get somebody killed eventually.)

What many outlets came down to was a non-amplification policy: Let Trump say whatever he wants, and if it’s too outrageous we just won’t pay attention. At a surface level that made sense: If he is saying these things to manipulate our attention, ignore him.

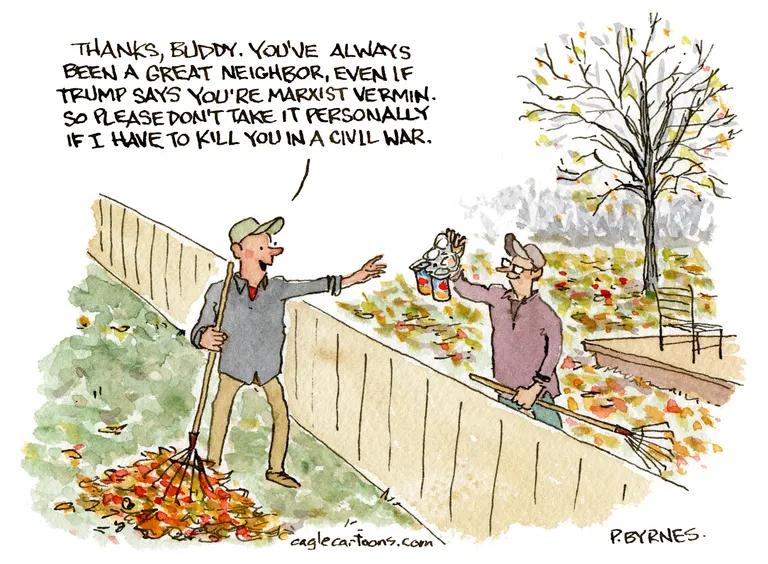

Now, though, we’re seeing the downside of that policy as well: For years, right-wing politicians have used “dog whistles”, turns of phrase that may sound innocuous to the average voter, but communicate a more sinister message to the politician’s extremist base. So, for example, you didn’t need to say openly racist things about Black people; if you simply talked about “the inner city”, your racist supporters would get your message.

Non-amplification, though, lets Trump get all the benefits of a dog whistle while opening saying what he means. For example, when he called his political enemies “vermin” a couple weeks ago, the major news outlets didn’t cover it right away. So his followers on Truth Social got the message, but the people he was implicitly threatening to exterminate didn’t. Likewise, his sharing of a fan’s fantasy of performing a “citizen’s arrest” on NY AG Letitia James and Judge Arthur Engoron escaped immediate national attention.

I don’t know why this is so hard: You don’t give Trump a live microphone to pass on disinformation. You never quote him without an immediate fact-check. But you do cover the fact of him making racist, violent, or authoritarian remarks.

Five co-authors at Columbia Journalism Review researched similar issues, and found that almost none of the major-outlet coverage of politics informed readers/viewers about the policy issues at stake.

Instead, articles speculated about candidates and discussed where voter bases were leaning.

The authors also found a major difference between the choices made on the front pages of The New York Times as opposed to The Washington Post: In the lead-up to the 2022 elections, The Times consistently emphasized issues that favored Republican narratives, while the Post was more balanced.

Exit polls indicated that Democrats cared most about abortion and gun policy; crime, inflation, and immigration were top of mind for Republicans. In the Times, Republican-favored topics accounted for thirty-seven articles, while Democratic topics accounted for just seven. In the Post, Republican topics were the focus of twenty articles and Democratic topics accounted for fifteen—a much more balanced showing. In the final days before the election, we noticed that the Times, in particular, hit a drumbeat of fear about the economy—the worries of voters, exploitation by companies, and anxieties related to the Federal Reserve—as well as crime. Data buried within articles occasionally refuted the fear-based premise of a piece. Still, by discussing how much people were concerned about inflation and crime—and reporting in those stories that Republicans benefited from a sense of alarm—the Times suggested that inflation and crime were historically bad (they were not) and that Republicans had solutions to offer (they did not).

and you also might be interested in …

Heather Cox Richardson reminds us of the true origin of Thanksgiving: The mythic “first Thanksgiving” of Native Americans and Pilgrims had been long forgotten when it resurfaced in 1841, and inspired a nation torn by the slavery question to imagine reconciliation. A Thanksgiving holiday did not become official until President Lincoln began proclaiming days of thanksgiving during the Civil War.

Cory Doctorow is one of the most interesting voices to listen to about technology and its influence on society. In this article, he talks about why the internet keeps getting less useful and more annoying, which he labels “the Great Enshittening”. X/Twitter is an obvious case in point, but it’s far from the only example.

The problem, he says, is structural change, not that tech people suddenly became villains.

Tech has also always included people who wanted to enshittify the internet – to transfer value from the internet’s users to themselves. The wide-open internet, defined by open standards and open protocols, confounded those people. Any gains they stood to make from making a service you loved worse had to be offset against the losses they’d suffer when users went elsewhere.

It follows, then, that as it got harder for users to leave these services, it got easier to abuse users.

In other words, inside tech companies there have always been arguments between people who want to extract more value from their users and people who want to give their users better service. But the argument against exploiting users was “if we do that, they’ll leave”.

In today’s internet, though, it gets harder and harder to leave an abusive platform for a less abusive one. (I’m still using X, for example, even as I experiment with alternatives.) So “if we do that, users will leave” isn’t as persuasive an argument as it used to be.

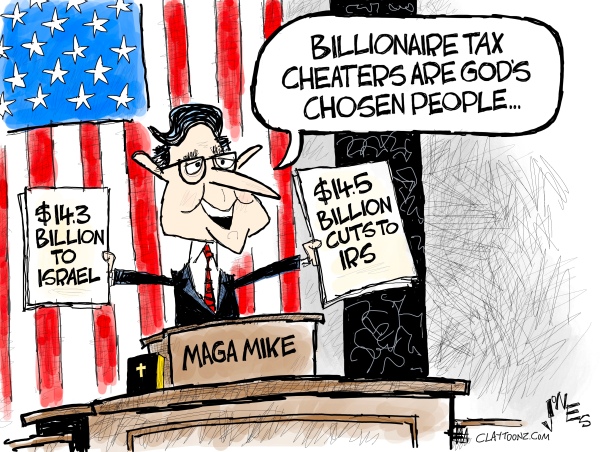

HuffPost has an article about the work Speaker Mike Johnson used to do as an attorney for the Alliance Defense Fund, a group trying to get the courts to recognize special rights for Christians. The article quotes Johnson making a point he still makes, claiming that “separation of church and state” is not only a “misunderstood” concept, but that when Thomas Jefferson originally used the phrase, he didn’t really mean what we think.

What he was explaining is they did not want the government to encroach upon the church, not that they didn’t want principles of faith to have influence on our public life.

Johnson is counting on people not looking up the letter where Jefferson coined the phrase. Here’s the key paragraph.

Believing with you that religion is a matter which lies solely between Man & his God, that he owes account to none other for his faith or his worship, that the legitimate powers of government reach actions only, & not opinions, I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their legislature should “make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,” thus building a wall of separation between Church & State. Adhering to this expression of the supreme will of the nation in behalf of the rights of conscience, I shall see with sincere satisfaction the progress of those sentiments which tend to restore to man all his natural rights, convinced he has no natural right in opposition to his social duties. [italics added]

The obvious corollary to Jefferson’s letter is that government can restrict actions, even if you justify your actions with some religious belief. So it’s fine if you want to believe that gays or transfolk are immoral, but if you want to turn same-sex couples away from your wedding-cake shop, that’s an action, not an opinion.

This week in When Bad Things Happen to Bad People: Derek Chauvin, the police officer convicted of murdering George Floyd, got stabbed in prison. And Kyle Rittenhouse, who became a right-wing hero after killing two people and shooting a third during the unrest following a police shooting in Kenosha, Wisconsin, is now broke, according to his lawyer.

He is working, he is trying to support himself. Everybody thinks that Kyle got so much money from this. Whatever money he did get is gone.

Not to worry, though, Rittenhouse has a book coming out. Crime may pay yet.

and let’s close with some holiday self-defense

Perhaps you’ve been lucky so far, and a few of your local retailers didn’t start playing “Jingle Bell Rock” until Black Friday. But for the next month or so all restraint is off, so you won’t be able to leave the house without hearing “Santa Baby” coming from somewhere.

I mean, some Christmas music is fine, and I’d probably miss it if I went a full season without any. But December is a whole month, and the Christmas playlist just isn’t that long. Even “O Holy Night” gets old if you hear it night after night after night.

So what you’ll need by December 25 is some off-beat Christmas music no one else is going to play, or maybe even some anti-Christmas music to channel your building resentment before it blows. Here are some of my favorites.

If you dread getting together with your dysfunctional extended family, the Dropkick Murphys have it worse than you do, and sing about it (with a very catchy tune) in “The Season’s Upon Us“.

You know that face you make when you were hoping for one kind of present and get something else entirely? Garfunkel and Oates have a song about it: “Present Face“.

It seems like every kind of place has a song explaining why Christmas so wonderful there. It’s become a formula and you can do it for anywhere, as Weird Al proved by collecting Cold War nostalgia in “Christmas at Ground Zero“. Similarly, the makers of South Park cranked out “Christmastime in Hell“.

South Park, it turns out, has an entire page of Christmas songs. Or if you want offbeat or unusual Christmas songs no one else knows about, there are entire playlists available on the web. You’re welcome.

Feel free to share your own rebellious seasonal music in the comments.