If we knew our history, we’d realize that the country is more resilient than we think.

Unprecedented. Every year, dictionary publisher Merriam-Webster announces a “word of the year“: a single term that in some way tells you what the year was about. Typically, it’s not a new coinage, but a common word suddenly getting more use. 2021’s word of the year was vaccine (though insurrection was a competitor), and 2020’s was pandemic. 2019’s word was an old pronoun being used in a new way: the singular they.

I don’t know what Merriam-Webster has in mind for 2022, but if it were up to me, the word of 2022 would be unprecedented. I seldom go a day without running across it somewhere.

All kinds of recent events are being cast as unprecedented. Just this week, Delta Airlines described a surge in fall air traffic as “unprecedented”. An ergonomic research group claimed recent strains on industrial workers are “unprecedented”. Tennessee Governor Bill Lee pitched an anti-crime proposal with a twofer: “Unprecedented times call for unprecedented measures.”

Both the Covid-19 pandemic and policies for containing it have been labeled “unprecedented”. Climate change has brought on all sorts of unprecedented events: not just heat waves, but droughts, storms, and floods.

But what makes unprecedented the word of 2022 is its eruption into American political news and discussions about the state of our democracy. No matter which side of the partisan divide you’re on, you see the other side doing unprecedented things that pose an unprecedented threat.

The FBI’s search of Mar-a-Lago was unprecedented, but so was the criminal activity that made it necessary. If the ultimate result is an indictment of a former president, that too would be unprecedented. The January 6th Committee’s vote to subpoena Trump wasn’t quite unprecedented, but sets up an “unprecedented” confrontation. The Committee’s hearings themselves have been unprecedented, but so was the riot (or insurrection or failed coup) they are tasked with investigating. A Trump-and-January-6 documentary released this summer was titled Unprecedented.

Day after day, we are being told that the current threat to American democracy is unlike anything that has ever happened before.

It’s a discouraging, dispiriting message, because it implies that we are on our own. History has nothing to teach us and offers no reassurances. If American democracy is Patient Zero of an previously unknown disease, who can advise us or make any predictions about our survival?

But what if our current predicament isn’t unprecedented? What if American democracy has faced crises before and muddled through them?

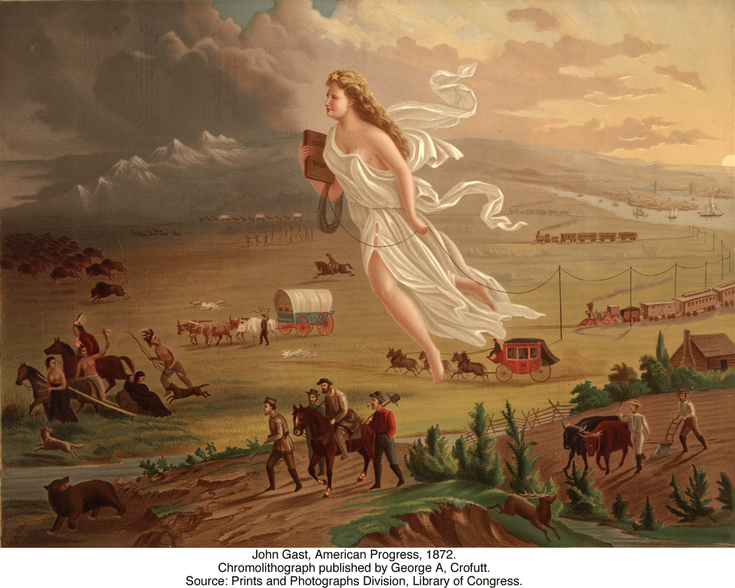

Historic blind spots. This is a point where the patriotic version of US history that most of us learned in high school fails us. We know about the Civil War, of course, and the Native American genocide (which used to be known as “how the West was won”). We know that Jim Crow walled Black Americans out of democracy in the South, and that women didn’t get the vote until 1920. Various consensual sexual acts were illegal for much of our history, and same-sex couples couldn’t marry until fairly recently.

But still.

The history I learned in school embedded those failings in a narrative of progress, in which democracy and human rights were constantly expanding. We made mistakes, but we fixed them. The villainies of our past are simply backstory for the heroic saga that followed.

This upbeat narrative is what Ron DeSantis wants Florida schools to teach today:

It was the American Revolution that caused people to question slavery. No one had questioned it before we decided as Americans that we are endowed by our Creator with unalienable rights and that we are all created equal.

So (in this telling) when Thomas Jefferson enslaved hundreds of human beings, took sexual advantage of at least one of them, and then raised his own children as slaves, he was foreshadowing abolition. His vision of human equality wasn’t hypocritical, it was prophetic.

While that onward-and-upward story may fill at least some Americans with a warm glow, it fails us in moments like these, when democracy itself is in trouble and human rights may be starting to contract. How can we cope with such unprecedented challenges?

But what if they aren’t unprecedented?

This week I spent some time examining two of the darker eras of American politics: I listened to the opening episodes of Rachel Maddow’s new podcast “Ultra“, about a fascist plot to overthrow FDR. And I read the new book by Smithsonian curator Jon Grinspan about the hyper-partisan politics of late 1800s, which he has dubbed The Age of Acrimony.

Ultra. The first episode of “Ultra” includes its own best introduction:

This is a story about politics at the edge. A violent, ultra-right authoritarian movement, weirdly infatuated with foreign dictatorships. Support for that movement among serving members of Congress who prove willing and able to use their share of American political power to defend the extremists, to protect themselves, to throw off the investigation. Violence against government targets. Plots to overthrow the United States government by force of arms. And a criminal justice system trying, trying, but ill-suited to thwart this kind of danger. …

This is a story of treachery, deceit and almost unfathomable actions on the part of people who are elected to defend the constitution, but who instead got themselves implicated in a plot to undermine it. A plot to end it. …

Perhaps most importantly, this is also the story of the Americans— mostly now lost to history— who picked up the slack in this fight, who worked themselves to expose what was going on, to investigate it, to report on it, ultimately to stop it.

And there’s a reason to know this history now. Because calculated efforts to undermine democracy, to foment a coup, to spread disinformation across the country, overt actions involving not just a radical band of insurrectionists, but actual serving members of congress working alongside them, that sort of thing is… that’s a lot of things. It’s terrible. But it is not unprecedented.

We are not the first generation of Americans to have to contend with such a fundamental threat. Lucky for us, the largely forgotten Americans who fought these fights before us, they have stories to tell.

“Ultra” begins with a mysterious 1940 plane crash that killed Minnesota Senator Ernest Lundeen, along with several government agents who had begun to shadow him. Lundeen was on his way to deliver a Labor Day speech that not only urged America to stay out of the war in Europe (where Hitler had already taken over France and was threatening Britain), it was openly pro-German, and “had been ghost-written for Senator Lundeen … by a senior, paid agent of Hitler’s government operating in America”.

There was a time when I considered myself a World War II buff. But I had never heard of Senator Lundeen, or of the insurrection plot described in Episode 2, for which 18 members of the Christian Front were arrested.

The participants in that plot were never convicted, largely because of the popularity of their cause.

Prosecutors were blamed for not appreciating— not factoring in to their jury presentation— just how favorably the Christian Front was viewed in the community where the trial was held. The local press affectionately nicknamed them “The Brooklyn Boys.” The local Catholic Church supported them loudly. Nobody who was Jewish was allowed to sit on the jury. There was a local Catholic priest who was advising the Christian Front, who had been leading rallies to support them, who was close to [Father Charles] Coughlin [who coined the term “Christian Front”]. His first cousin was picked as the foreman of the jury.

And yet democracy was not overthrown by fascism, not in 1940 and not since. We’ll have to wait for future episodes (Episode 3 just posted this morning) to find out what Rachel thinks we can learn from democracy’s survival.

The Age of Acrimony. Eight years ago, in the most popular Sift post ever, I first pointed to the biggest hole in my US history education: Reconstruction.

In my high school history class, Reconstruction was a mysterious blank period between Lincoln’s assassination and Edison’s light bulb. Congress impeached Andrew Johnson for some reason, the transcontinental railroad got built, corruption scandals engulfed the Grant administration, and Custer lost at Little Big Horn. But none of it seemed to have much to do with present-day events.

And oh, those blacks Lincoln emancipated? Except for Booker T. Washington and George Washington Carver, they vanished like the Lost Tribes of Israel. They wouldn’t re-enter history until the 1950s, when for some reason they still weren’t free.

Reconstruction and much of the Gilded Age get skipped over because (in every area but technological advancement and GDP growth) they don’t fit very well into the ever-upward narrative of American progress. As Grinspan tells the story:

Americans claim that we are more divided than we have been since the Civil War, but forget that the lifetime after the Civil War saw the loudest, roughest political campaigns in our history. From the 1860s through the early 1900s, presidential elections drew the highest turnouts ever reached, were decided by the closest margins, and witnessed the most political violence. Racist terrorism during Reconstruction, political machines that often operated as organized crime syndicates, and the brutal suppression of labor movements made this the deadliest era in American political history. The nation experienced one impeachment, two presidential elections “won” by the loser of the popular vote, and three presidential assassinations. Control of Congress rocketed back and forth, but neither party seemed capable of tackling the systemic issues disrupting Americans’ lives. Driving it all, a tribal partisanship captivated the public, folding racial, ethnic, and religious identities into two warring hosts.

In hindsight, it’s hard to cast either Democrats or Republicans as the heroes of late 19th-century politics. Democrats were the proud descendants of the Confederacy in the South, combined with the corrupt big-city political machines of the North. On the other side, Republicans soon abandoned the ideals of Reconstruction and 15th Amendment’s new Black voters in favor of the vast business empires of the Rockefellers and Morgans.

More and more of the country was being herded into an impoverished urban proletariat that neither party truly represented. Republicans were on the opposite side entirely, while Democrats would “help” by distributing patronage jobs to loyal party members. Neither party saw a structural problem requiring the kinds of solutions that wouldn’t appear until the 20th century: a minimum wage, workplace safety laws, bans on child labor, unemployment insurance, an old-age pension, and protection for union organizers.

What political campaigns lacked in substance, they made up in noise. Both parties had militaristic marching clubs not entirely unlike the Nazi storm troopers of the 20th century, and torchlight parades were common demonstrations of political strength. Neighborhood political centers were typically saloons where glad-handing ward bosses would pour free drinks in exchange for votes.

The spoils system, in which the victorious party handed out government jobs to those who worked hardest on the campaign, was not a dirty secret, but rather an orderly process that people counted on. President Garfield was assassinated not by an ideological terrorist or a lunatic looking for fame, but by a disgruntled member of his own party who felt his electioneering efforts should have earned him a plum appointment.

The result of all this was a widespread belief that democracy had failed. In 1878, one of the era’s top American historians, Francis Parkman, wrote “The Failure of Universal Suffrage“.

When a man has not sense to comprehend the questions at issue, know a bad candidate from a good one, or see his own true interests — when he cares not a farthing for the general good, and will sell his vote for a dollar — when, by a native instinct, he throws up his cap at the claptrap declamation of some lying knave, and turns with indifference or dislike from the voice of honesty and reason — then his vote becomes a public pest. Somebody uses him, and profits by him.

Rule by the majority, it seemed, meant rule by the ignorant and the easily manipulated. No one appeared to know what to do about it. Parkman, for example, didn’t want a king, and thought any attempt to restrict the vote would be impractical: The People would never give up their power voluntarily, no matter how little good it was doing them. And politicians would never agree to change the system that had put them in power.

Journalist Lincoln Steffens examined seven large political machines, and assembled his conclusions in magazine articles that were reprinted in his 1904 book The Shame of the Cities.

When I set out on my travels, an honest New Yorker told me honestly that I would find that the Irish, the Catholic Irish, were at the bottom of it all everywhere. The first city I went to was St. Louis, a German city. The next was Minneapolis, a Scandinavian city, with a leadership of New Englanders. Then came Pittsburg, Scotch Presbyterian, and that was what my New York friend was. “Ah, but they are all foreign populations,” I heard. The next city was Philadelphia, the purest American community of all, and the most hopeless.

The problem, Steffens concluded, wasn’t any specific group, and it wasn’t the politicians. It was the people in general. Hoping that electing businessmen would improve the system (a perennial claim of businessmen) was pointless, because the politicians were already businessmen. They supplied what the electoral market wanted: corruption.

If we would vote in mass on the more promising ticket, or, if the two are equally bad, would throw out the party that is in, and wait till the next election and then throw out the other party that is in—then, I say, the commercial politician would feel a demand for good government and he would supply it.

But the electorate wouldn’t do that, leading Steffens to this conclusion:

The misgovernment of the American people is misgovernment by the American people.

And yet, somehow, things began to turn around. They had, in fact, already started their long slow turn when Steffens was making his tour.

Solutions? One aspect of Grinspan’s book that is alternately annoying and satisfying is that he has no concise explanation of how change happened. He’s very clear that it didn’t happen all at once, and there was no obvious turning point. Neither party took on the job of reform, and no Gilded Age Solon designed an improved political system.

The change seems to have been primarily cultural rather than political or legal. Systemic changes were the result, not the cause.

It is tempting to tell this story solely as an evolution of law, of amendments ratified granting wider and wider access. But the driving force behind our changing system has been America’s popular culture, the way we use politics.

The widespread conviction by people of both parties that the current system was distasteful and embarrassing led, over time, to a long series of changes, no one of which stands out as the pivot point.

- Secret ballots. Believe it or not: “Before the final years of the 19th century, partisan newspapers printed filled-out ballots which party workers distributed on election day so voters could drop them directly into the boxes.” Between 1885 and 1891, all the states (acting on their own) switched to more-or-less the current system: An official ballot is printed by the government and given to voters at the polling place, where they fill it out in secret.

- Civil service. The Pendleton Act was passed in 1883, establishing a merit system for jobs in the federal bureaucracy. State governments soon began passing their own versions.

- Mass-market advertising. The new business model of newspapers and magazines aimed at offering advertisers near-universal distribution, rather than niche-marketing to a partisan audience. (Why would Coca-Cola want to be known as a Republican or Democratic drink?) This paved the way for standards of objectivity. Mass media has never truly been objective, and there’s some debate whether that idea even makes sense. But prior to, say, 1920, objectivity was not even an aspiration for most newspapers.

- Parties changed their campaign styles. The torchlight parades and saloon headquarters became unfashionable, too reminiscent of the fat-cat politicians skewered by the newspaper cartoonists. Campaigns started focusing more on platforms, pamphlets, and buttons — things that you read or wore rather than things that you did.

- Reformers began learning the nuts-and-bolts of politics and getting their hands dirty. In the post-Civil-War era, politics was considered a odious profession, unbecoming to a gentleman. One positive point in Parkman’s essay is a plea for idealistic and well-educated people to run for office. Over the next few decades many did.

- States provided tools for direct democracy. The referendum and recall processes come from this era.

- Political energy shifted away from the two major parties and into causes. Rather than crusading as a Republican or Democrat, you might instead devote yourself to temperance or free coinage of silver or women’s suffrage.

Very little of this was decided in elections. For example, neither party was visibly for or against the secret ballot. it didn’t take hold in one part of the country but not another.

Not all the changes were positive: This was also the era when Jim Crow was being established in the South, and the Chinese Exclusion Act passed.

And some of the beneficial developments had dark sides that we have since forgotten. A printed ballot listing all candidates also served as voter suppression: Illiterate or drunk voters might not be able to recognize candidates’ names. Southern Democrats supported the Pendleton Act because the spoils system kept allowing Republican presidents to give good jobs to their Black supporters. Temperance was a way of shutting down the saloons and taverns where working people might gather and plan.

Today, saying that a change requires a constitution amendment is equivalent to admitting that it can’t be done. But four constitutional amendments passed between 1913 and 1920: the federal income tax, direct election of senators, prohibition, and women’s suffrage.

Perhaps the oddest story of the change concerns women’s suffrage. The proposal was going nowhere in the 1880s, because politics was so obviously masculine. Who wanted his wife or daughter marching with a partisan militia, and possibly brawling with a similar group from the other party? Or hanging around in saloons getting men drunk and asking for their votes?

In a weird way, women’s inability to vote or run for office stimulated the push towards causes. Women were largely immune to the hoopla that gave men their political identities, and often diverted them away from their real interests. Undistracted by party politics, a woman might instead devote her energy to crusading for temperance or against lynching. She might organize a union or co-found the NAACP.

Giving women the vote in 1920 isn’t what changed politics. It was only because politics had changed that men could imagine including women in it.

What can we learn? Neither the 1940s nor the Gilded Age is exactly like the present era, and neither provides a blueprint for democracy’s survival. But both, I think, provide a context that give us reasons to hope.

A rose-colored view of our history, one that tells our story as one of continuous progress towards freedom and inclusion, can make us feel uniquely beset today. But in many ways democracy has always been a struggle, and the battle is never completely won.

But knowing about our past struggles may allow us to hope that American democracy is more resilient than we have been thinking. Reforms that seem impossible in one decade can become obvious in the next. The pivotal moments of history are hard to spot, because they’re probably happening inside the culture rather than in Congress.

Things may have already started to turn, and we just don’t see it yet.

Comments

Thanks, Doug, for identifying this podcast and this book. They’re both on my listen/read lists.

Rich

Doug, more than any other of your essays, this belongs in the Washington Post or NY Times. – a well documented, fresh look at the tsunami below the tides of social ferment.

Thank you. I’ve been extremely anxious as the election draw nearer, and I’ve noticed an alarming hysteria from too many news sources. I live in a semi-rural area, and have been harassed for daring to post pro-Democrat signs on my own property! Lately the harangues and threats have gotten louder and fouler. I remain convinced that means the bullies are absolutely terrified they are losing. This piece really boosted my resolve to not back down.

I don’t read this blog every day, but when I do, it’s always a blockbuster!

I just turned 75 the other day, and I find myself trying to remember history from my school days. (I graduated from HS in 1965.) I’m learning more American history now than I ever did back in the day.

“The history I learned in school embedded those failings in a narrative of progress, in which democracy and human rights were constantly expanding. We made mistakes, but we fixed them. The villainies of our past are simply backstory for the heroic saga that followed.”

The truth of the above statement is still (and maybe more) true today.

Pulitzer Prize material here.

Reminded of the lion statues at New York’s Public Library named during the Depression: Patience and Fortitude.

This is excellent, Doug. I try not to fall into the “first they came for the Jews” way of thinking, even in scary times. There are decades of social and evolutionary psychological research into our binary, good-and-evil habits of viewing the world, with the upshot being pretty much that we just don’t deal well with complexity (i.e., the real world). And, of course, social media has turbocharged demonizing-and-idolizing. We want simple cause-and-effect explanations (and predictions), and seem all but incapable of recognizing that contingency is ever present. The future throws us curveballs all the time. Thanks!

To feel optimistic again, read Thomas Piketty

about the historical, albeit, dialectical road to equality. Start with Capital and Ideology, then read Brief History of Equality, backed by historical anslysis and social science data.

I can’t share your optimism. The comparisons to history are too different. We’re not facing a serious risk of a violent coup. January 6 was our Beer Hall Putsch; an important warning, but not itself a real danger. We’re also not facing a simple flip-flopping of power as greedy parties fight dirty.

One party has abandoned any pretext of caring about the law while simultaneously rewriting the rules to cripple their law-abiding opponents.

So I look to Venezuela. A Supreme Court captured by authoritarians that proceeds to ignore precedent and obvious constitutional limitations to just hand the authoritarians what they want. What are Democrats going to do if our Supreme Court announces that despite no evidence there was rampant fraud and so Trump wins the 2024 election?

And I look to Hungary. A constitution that leads to parties regularly getting legislative seats wildly out of alignment with voting results. A party willing to use the law to attack businesses that don’t toe the line. Aggressive gerrymandering for political advantage. An equivalent of our Senate, where a low-population, pro-authoritarian district gets the same number of representatives as a high-population, opposition district. First-past-the-post elections. Fake candidates and parties to confuse and divide the opposition. These are challenges we have today, and the Democrats have shown a complete inability to deal with them.

despite excellence of your research weekly -thank you- you neglect the populist party, the wobblies, the socialists , the farmers alliance, eugene debs , the nascent labor movement etc- there IS an answer to your query about how did it change – hard grass roots effort

These coup-plots are more frequent than we realize. Google “plot to overthrow FDR” to find information about a plot by Wall Street bigwigs to overthrow FDR just 8 years before the Ultra plot.

Linda

Honestly, I don’t particularly want to live the rest of my life having to refight these battles that were already won. Or live through another Gilded Age or Great Depression because we elect corrupt elites who are allowed to operate above the law and without responsibility while making life more difficult, if not impossible, for the rest of us. I’m 51 years old, so my personal experience with history (that I can actually remember) doesn’t really start until at least the late 1970s. But I was under the impression that people like my Grandmother fought these battles so I wouldn’t have to. That there are so many people who want to do it all again is the existential threat. Even if Democracy survives and later thrives in the US, there’s the threat that I will have to watch my children suffer through the interim while Ted Cruz gets fatter and fatter.

Good current reforms would be ranked choice voting and ending gerrymandering. It would also be good to come up with a ggod name for the opposite of gerrymandering. Then we could talk about what we want, rather thn what we don’t want.

Trackbacks

[…] This week’s featured post is “American Democracy has been in trouble before“. […]

[…] https://weeklysift.com/2022/10/17/american-democracy-has-been-in-trouble-before/ American democracy has been in trouble before […]