Did General Milley take steps to prevent a coup or to participate in one?

On paper, the American chain of command is simple: The Constitution makes the President commander-in-chief. Typically, he exercises that authority through a civilian Secretary of Defense and a hierarchy of generals, but nothing about that is necessary. On paper, the President can give orders to any soldier.

That authority over the entire military is summed up by an LBJ anecdote: As he was preparing to leave a military base, President Johnson walked toward the wrong helicopter until a young officer stopped him, saying “Your helicopter is over there, sir.” Johnson is supposed to have replied, “Son, they’re all my helicopters.”

At any level of the American military, though, there is an exception for illegal orders. If a superior tells you to execute prisoners, for example, you can say no. But you can well imagine that the bigger the gap in authority, the harder that “no” would be. Could a private or a green lieutenant really say no to a president?

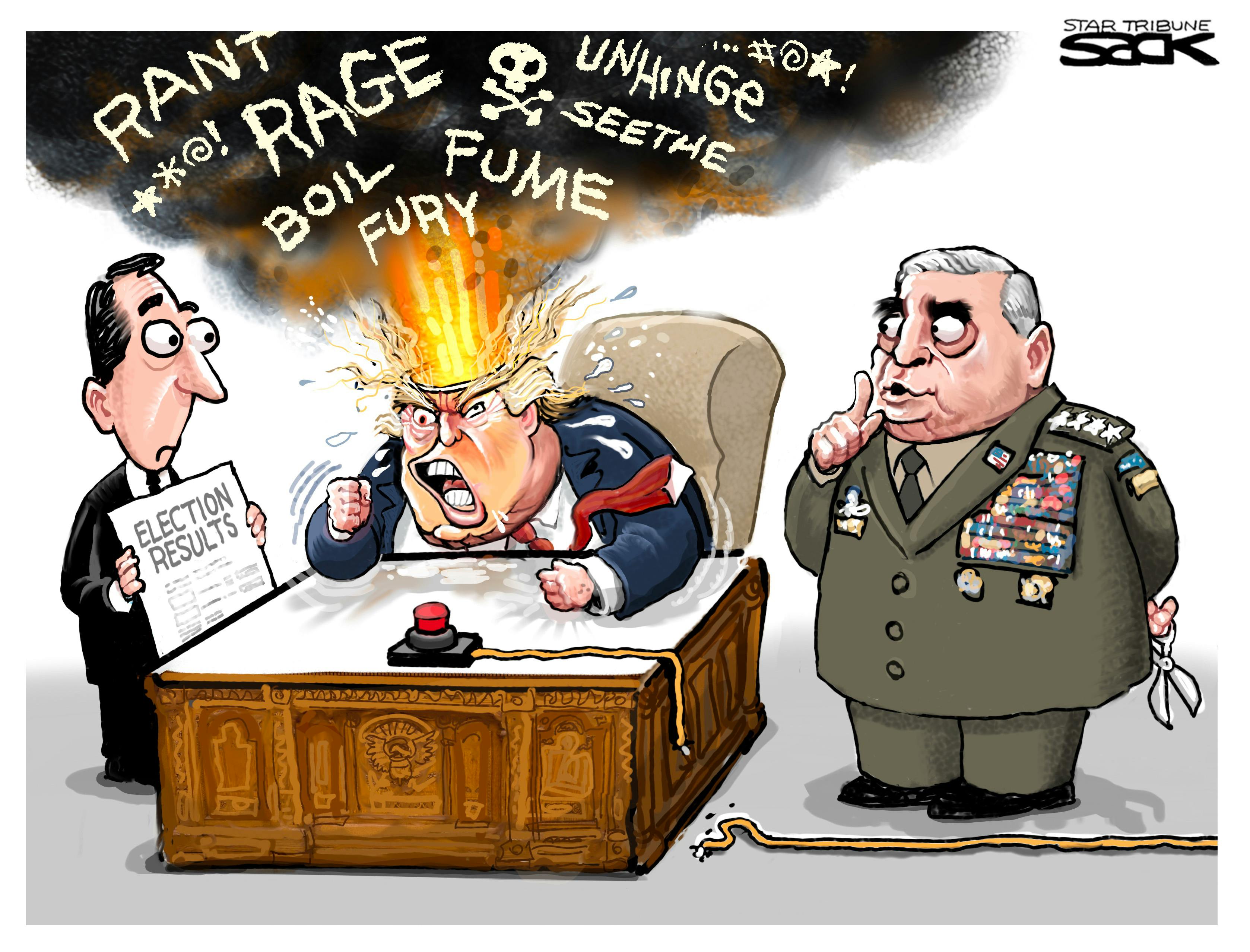

And that brings us to the aftermath of the January 6 insurrection. According to accounts from CNN and The Washington Post of the still-unpublished book Peril by Bob Woodward and Roberta Costa, Joint Chiefs Chair General Mark Milley did two questionable things in the late days of the Trump administration. [1]

- Milley made two phone calls (October 30, 2020 and January 8, 2021) to his Chinese counterpart to say that America was not planning an attack on China.

- He instructed military officers not to execute any attack orders from the White House without consulting him.

Critics have a made a big deal about the China calls, but this appears to be fairly normal behavior in crisis situations. American military officers frequently cultivate personal relationships with their counterparts in other countries, and use those connections to smooth over possible misunderstandings. Politico reports:

A defense official familiar with the calls said … the calls were not out of the ordinary, and the chairman was not frantically trying to reassure his counterpart.

The people also said that Milley did not go rogue in placing the call, as the book suggests. In fact, Milley asked permission from acting Defense Secretary Chris Miller before making the call, said one former senior defense official, who was in the room for the meeting. Milley also briefed the secretary’s office after the call, the former official said.

But the second revelation raises more serious issues.

Woodward and Costa write that after January 6, Milley ‘felt no absolute certainty that the military could control or trust Trump and believed it was his job as the senior military officer to think the unthinkable and take any and all necessary precautions.’Milley called it the ‘absolute darkest moment of theoretical possibility,’ the authors write.

Milley’s fear, I surmise, was that Trump would skip over the top military leadership and directly order some junior officer to take extreme (and possibly illegal) military action, which could be either a wag-the-dog foreign attack or a coup at home.

This apparently did not happen. But it was not an unreasonable scenario to plan for, especially given what was going on in the Justice Department, where Trump was going over the head of the Attorney General to push investigations and public statements in support of his stolen-election lie.

What Milley did, though, raises questions about civilian control of the military. Might the generals, at some point, simply refuse to obey presidential orders they disagreed with? And if those orders are illegal, or arise from “serious mental decline” (as the book says Milley believed about Trump), should they?

On paper, responsibility to protect the country from an insane or mentally incapacitated president lies with the vice president and the cabinet, who can remove the president via the 25th Amendment. No military officer plays any role in that process.

But what if they’re not doing their job? If you’re the person getting the crazy orders, does that responsibility fall to you, no matter what the Constitution says?

These questions point to a grey area in our system: If you believe that the train of constitutional government has already jumped its rails (say, because the president is planning or executing a coup), at what point do you take (or prepare to take) extra-constitutional actions yourself?

I don’t have a good answer to that question.

Republicans like Josh Hawley and Marco Rubio have called for Milley to be fired, while President Biden has expressed confidence in him.

I have trouble taking Hawley seriously, given his own treasonous inclinations. But I give more weight the critique of retired Lt. Colonel Alexander Vindman, who Trump fired (along with his brother) in retribution for Vindman’s testimony at Trump’s first impeachment. He also believes that Milley should resign or be fired.

In recent years, too many leaders have succumbed to situational ethics, and the public has looked the other way when people considered those leaders part of their faction. Doing the wrong thing, even for the right reasons, must have consequences. Many people in the Trump administration — including me — resigned or were fired exactly because they did the right things in the right way. Milley may have done the wrong thing for the right reasons. But the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff does not deserve greater consideration for doing the wrong thing — he deserves greater scrutiny. As my friend and former Pentagon official John Gans tweeted: “You can break norms for a greater good, but that often comes with a price. Paying it is the only way to ensure the norms survive for the next time.”

That do-it-and-face-the-consequences path reminds me of my analysis of the ticking-bomb scenario. Remember? The Bush administration believed CIA agents should be able to torture terrorism suspects, because doing so might save lives if the suspect knew about a ticking bomb. The law, I wrote at the time, should never authorize torture in advance. In the unlikely event that an American official found himself in a ticking-bomb situation, and was certain that torturing a suspect would save many lives, the right move would be to break the law, and then confess and trust the mercy of a jury. Do it if you think you must, but don’t hide from the consequences. An official who isn’t willing to risk a jury disagreeing shouldn’t be torturing anybody.

Similarly, I think Milley should have made a full public confession as soon as the crisis had passed. (After Biden’s inauguration, say.) In a roundabout way, he has done this by talking to Woodward and Costa. [2] He will be appearing before Senate Armed Services Committee a week from tomorrow, where I suspect he will be asked a lot of questions related to the Peril revelations.

However, I think Republicans should approach this hearing carefully. At some point a Democrat might ask, “What specific behavior did you witness personally that convinced you that President Trump had undergone ‘serious mental decline’ after his defeat in the November elections?” Whatever else the hearing might uncover, the answer to that question is likely to be the headline.

[1] When you think about this story, you need to bear in mind how far we are from the root facts: The general public can’t even see the book until tomorrow. CNN and the WaPo are summarizing what Woodward and Costa report that various newsmakers told them. Even if you trust everybody involved, it’s still third-hand information.

[2] I am assuming the quotes attributed to Milley come from direct interviews.

Comments

Regarding your last point, I think the exact wording matters a lot here. The military has a chain of command for a reason, and reminding subordinates they take their orders from you, and only you, is perfectly appropriate. If a superior wants something to happen, they should order you to direct it, and can remove you if you refuse. Going around you is wrong, and instructing subordinates to refer that person back to the chain of command is the right thing to do. All of which is subtly different from telling someone to disobey a direct order.

The absence of sourcing throughout Peril is understandable. In general, it is acceptable from such well regarded reporters as these two authors. Still, even if the source of these conversations was Gen. Milley, more needed to immediately surround the quoted passage for it to have less valid criticism and more impact.

I think your wording here needs work:

“According to accounts from CNN and The Washington Post of the still-unpublished published book Peril by Bob Woodward and Roberta Costa”

You should state “the soon-to-be-published book” and that will get the same content across instead of the sentence as is.

You’re right. The second “published” was a typo.

Regarding the 2nd revelation, “Milley ‘felt no absolute certainty that the military could control or trust Trump and believed it was his job as the senior military officer to think the unthinkable and take any and all necessary precautions.” While I get that its concerning that his thought process took him to this point, did he actually do anything wrong? I’m not seeing any action that would warrant his removal. I mean, I can think about robbing a bank all I want.

If the account in “Peril” is trustworthy, the agreement with other military people was of the wink-and-nod variety. I think they knew they were getting ready to disobey a presidential order if the wrong one came down, but no one precisely said that.

Even though juries are told to decide if the facts presented prove that the law was violated and that the defendant is guilty beyond a reasonable doubt, juries can and do nullify the law when they feel justice is best served by a not guilty verdict. The court and the lawyers won’t/can’t inform the jurors about jury nullification, but it’s a reality. Personally, I’d like to believe that our top career military leaders are like Milley, willing to exercise moral discretion when the stakes are high, and less like those who would without thought or question follow any command.

What concerns me about the hand-wringing over Milley’s behavior in this is that it is an example of legitimizing the behavior of the Trump Administration. Trump, and those around him, violated numerous norms to ruinous effect. If we insist that all of those serving his presidency were expected to follow all of the norms of a less extreme (and extremely dangerous) administration, the implication is that the administration was “normal.”

Sure, it would have been appropriate for Milley to come forward with an account of what he did and an explanation of why he did it once the dust had settled, but I think it is missing an important point to condemn him for breaking the norms in an extraordinary situation. That’s exactly when norms are supposed to be broken.

I wasn’t trying to condemn Milley, but rather point out that the account of his behavior in “Peril” raises some uncomfortable questions.

Trackbacks

[…] This week’s featured post is “Seven Days in January“. […]

[…] book Peril (that last week’s post “Seven Days in January” was indirectly based on) came out Tuesday, and I rushed to read it. I didn’t find any […]