Presidential elections are rigged in favor of Republicans. North Dakota wants to keep it that way.

As we’ve seen in the last two elections, the Electoral College gives the Republican candidate about a 3-4% advantage, which might be growing as the rural areas (which the EC over-weights) get more conservative and the cities (which it underweights) more liberal.

Hillary Clinton won the 2016 popular vote by 2.1% but still lost the election, and Biden’s 4.4% victory in 2020 goes away if you lower his margin by .7% across the board. (He loses Arizona, Georgia, and Wisconsin, leading to a 269-269 tie that the House — with one vote per state delegation — would have decided in Trump’s favor.) Hillary would still have lost if you similarly boosted her margin in every state by .7%.

So the Electoral College’s thumb-on-the-scale was worth about 2.8% in 2016 and 3.7% in 2020. Republicans like to talk about “rigged elections”. Well, they’re right: Presidential elections are rigged in their favor.

The straightforward way to unrig our elections would be to pass a constitutional amendment eliminating the Electoral College and awarding the presidency to the candidate who gets the most votes. But that path requires a 2/3rds majority in both houses of Congress and ratification by 3/4ths of the states, so it can’t pass without bipartisan support. Few Republicans have a sense of fair play or respect for democracy, so they’re not going to give up the unfair advantage the EC gives them. [1]

An alternative scheme for unrigging our elections is the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact: States agree to appoint electors for the candidate who wins the national popular vote, even if that candidate didn’t win in their particular state. If states representing 270 electoral votes all passed a law joining the compact and fulfilled their commitments, the Electoral College would never screw the American people again.

I have mentioned before that, as much as I like this idea, I would never trust this agreement. In 2020, we saw how many bad-faith actors hold positions of authority in the Republican Party. (Though most Republican election officials did their jobs honestly; Biden could not have won without them.) It was hard enough to feel secure that Republican legislatures wouldn’t step in and illegitimately award their electors to Trump, even though he got fewer votes both in their states and in the nation as a whole. If a Republican legislature in a place like Georgia or Wisconsin could give a Republican the White House just by agreeing with the voters in their state, I have to believe they would, no matter what commitments they might have made previously. [2]

Well, it looks like messing up the NPVIC is even easier than I had thought. North Dakota, owner of exactly three electoral votes, may be about the skewer the whole thing: The state senate has passed a law that forbids state election officials to release their popular vote totals until after the Electoral College meets.

[A] public officer, employee, or contractor of this state or of a political subdivision of this state may not release to the public the number of votes cast in the general election for the office of the president of the United States until after the times set by law for the meetings and votes of the presidential electors in all states

The upshot is that there would be no official national popular vote total. Compare this to the process laid out in the NPVIC:

Prior to the time set by law for the meeting and voting by the presidential electors, the chief election official of each member state shall determine the number of votes for each presidential slate in each State of the United States and in the District of Columbia in which votes have been cast in a statewide popular election and shall add such votes together to produce a “national popular vote total” for each presidential slate.

The chief election official of each member state shall designate the presidential slate with the largest national popular vote total as the “national popular vote winner.”

The presidential elector certifying official of each member state shall certify the appointment in that official’s own state of the elector slate nominated in that state in association with the national popular vote winner.

If everyone involved would carry out the spirit of this agreement in good faith, probably there would be no problem. It’s extremely unlikely that North Dakota’s votes would make the difference in the national popular vote, so even without knowing their totals, the popular-vote winner should be apparent. In 2016, for example, only 344K votes were cast in North Dakota, and Hillary won nationally by 2.9 million.

But now let’s talk about the real world, where bad-faith actors abound. If I’m, say, a Republican official in 2016 Wisconsin, where a good-faith application of the NPVIC would have me appoint pro-Hillary electors even though Trump won my state, I can claim that without the North Dakota votes the conditions of the NPVIC have not been fulfilled. Would the Republican legislature or a Republican-appointed judge overrule me? I kind of doubt it.

So I think the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact is dead. This particular hole could be patched without a constitutional amendment, if Congress could pass a law (over a Republican filibuster) mandating that states release their vote totals in a timely fashion. But I think this would just start a game of whack-a-mole. And what if a red state whose vote totals do matter, like Texas, decides to play?

I think the monkey-wrenchers win this battle, and we’re stuck with the Electoral College until we can muster a constitutional amendment.

[1] Electoral College advocates sometimes hide their partisan intentions by making arguments that sound good, but don’t hold up to even a small amount of scrutiny. For example:

A presidential campaign aimed at achieving a popular vote majority would completely ignore most states and focus, instead, on a few populous states containing the nation’s largest cities. This urban-centric strategy would silence the political voice of most regions of the country.

Anybody who has lived in a state with a big city knows this isn’t true. If it were, no Illinois candidate would ever leave Chicago, Texas campaigns would only happen in Houston and Dallas, and Florida candidates would camp out in Miami. They don’t — and for good reason. Consider, for example, the map of the Ted Cruz/Beto O’Rourke Senate race of 2018. Cruz lost just about all the cities — Houston, Dallas, San Antonio, El Paso — but won anyway because the rural areas came through for him.

In a popular-vote system, candidates look for votes wherever they think they can get them, because all votes count the same. Convincing somebody to vote for you in Chugwater, Wyoming counts just as much as convincing somebody in Los Angeles.

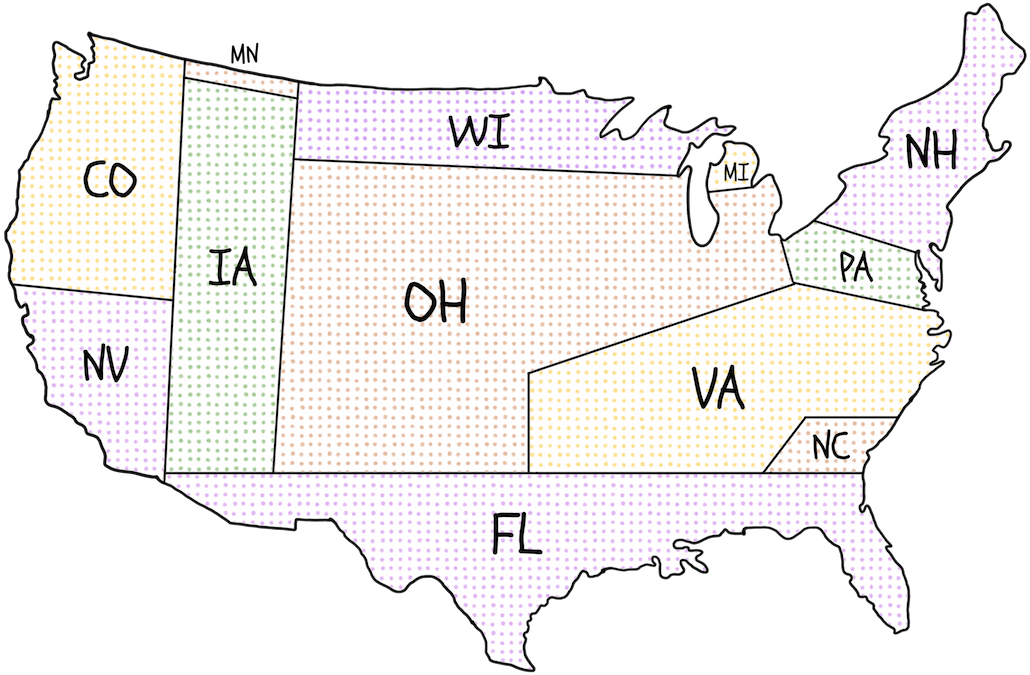

In fact, if you apply the make-them-campaign-everywhere argument honestly, it will point you in exactly the opposite direction: Because of the Electoral College, presidential candidates only campaign in swing states like Pennsylvania and Florida, and ignore most of the American people. Here’s a map where states are sized according to how many presidential campaign events happened there in 2012. Three of the four biggest states — California, Texas, and New York — don’t even show up. But neither do small states like Alaska, Utah, or Rhode Island, because nobody bothers to compete in states where the electoral votes aren’t up for grabs.

In a popular-vote system, it would make sense for a Democratic candidate to campaign in, say, the Black neighborhoods of Memphis or the Hispanic areas around El Paso — because there are people there who might be convinced to vote for you. Similarly, a Republican candidate should hold rallies in upstate New York or conservative Chicago suburbs. But they don’t, because in the Electoral College system, competing for votes that won’t tip a whole state is wasted effort.

So in fact it’s the Electoral College that silences “the political voice of most regions of the country”.

[2] The Compact tries to deal with the question of states changing their minds:

Any member state may withdraw from this agreement, except that a withdrawal occurring six months or less before the end of a President’s term shall not become effective until a President or Vice President shall have been qualified to serve the next term.

But there is no enforcement mechanism, and a basic principle of our system of government says that no legislature can claim power over a future legislature. (As Jefferson put it: “The dead should not rule the living.”) So if Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and Michigan had joined the compact in 2015, and then in 2016 one of them passed a law refusing to award their electors to Hillary, I think Trump still becomes president. States might sue each other later, but the deed would be done.

Comments

That is a very clever move, but really unfortunate that the net effect of the NPV so far might be to degrade democracy by reducing transparency. The Constitution does not require states to even conduct a vote. That aside, my preference would be to not accept the electoral college votes of any state that did not publish their vote totals, preferably at the district level so it can be checked.

If the compact were in place by a state before the election and it was in effect due to enough states having joined there would be a pretty good case to enforce that the state abides by the compact.

The way that the compact is enforced is through state law. States can change the law, but that does not mean that they can change the law of an election after the election has occurred.

Have you previously explained Elizabeth Warren’s wealth tax? I love the idea of having the richest of the rich pay their fair share but I worked at IRS for 30 years and I cannot imagine how someone’s “wealth” could be identified in order to be taxed. Wouldn’t it be more accurate to just revise the tax rates and close loopholes? Jackie Reilly Kyle, TX

Until we get a constitutional amendment that institutes a popular vote, I suggest we fix what we can. The ‘easiest’ fix would be to increase the membership of the House of Representatives. Because the number has been fixed since the early 1900’s (for over 100 years) and every state gets at least one house member, there are 7 states (AK, DE, MT, ND, SD,VT, WY) with populations so low they get only one house member. That means people in more large population states are under represented. California has only 53 representatives in the house, whereas, if California districts matched the population size of Wyoming they’d have 68! That is a 20% under representation! The fix is easier than a constitutional amendment. Just pass a law that says that the number of representatives in a state is based on its population size divided by the lowest population state, with some provision for rounding up or down. Will it fix all the problems? No. It will address an institutional bias in the law that doesn’t need to be there. And it can pass with simple majorities in Congress and the president’s signature. Seem like a much easier lift. And the electoral college vote will more closely match the popular vote.

Jacoby, that’s a nice idea about changing the number of representatives per state.

Another fix would be fairly simple, though it would still rely on getting a few more states to join the NPV compact: each of the states in the compact would have to pass a small amendment stating that in case a state doesn’t release their vote totals, that state’s votes wouldn’t be counted.

A data point: I calculate the lowest popular vote that could still win the presidency to be 22.87%, much lower than I expected. That assumes the extreme case where a candidate wins all of the smallest population states by one vote. Amazing what 2 extra electoral votes can accomplish.

mikelabonte, I would love to see your list of states that can win the election with just 22.87% of the national popular vote. Does it turn out to be a list of all the lowest population states until you get up to 270 electoral votes?

Yes pauljbradford, it is simply a matter of putting the states in order of population and cutting off once 270 electors are accumulated, using a margin of just one vote in each state. The spreadsheet does not try to consider turnout or even eligibility to vote; it assumes everyone can vote. The assumption is that those scale to the population, and in the end we get just a percentage anyway. It also assume NE and ME are winner-take-all states, which they aren’t.

https://www.icloud.com/iclouddrive/04W3HAjQzbDeB-Laj24umb3Xg#LowestPopularVoteCalc

The spreadsheet starts with Wyoming and New Jersey becomes the state that brings the elector total to 279. At that point voters representing 75 million out of 327 million people have elected the winner.

Trackbacks

[…] North Dakota Is About to Kill the National Popular Vote Compact — The Weekly Sift […]

[…] week’s featured posts are “North Dakota Is About to Kill the National Popular Vote Compact” and “The Action Shifts to […]

[…] https://weeklysift.com/2021/03/01/north-dakota-is-about-to-kill-the-national-popular-vote-compact/ North Dakota Is About to Kill the National Popular Vote Compact […]