American democracy only works if the Senate works.

At the moment the two biggest stories in American politics are the impeachment of Donald Trump and the long-anticipated inauguration of Joe Biden. Both stories, at their root, are about the continuance of democracy.

Biden’s inauguration may be sparsely attended, socially distanced, and observed by enough troops to conquer a medium-sized country, but fundamentally it will be a celebration of the peaceful transfer of power. In spite of a long list of bad-faith challenges, culminating in a right-wing mob attacking the Capitol itself, the American People will get the president they elected.

Trump’s impeachment is in some sense the flip side of that same coin. When a president tries to hang on to power in spite of the People, even to the point of inciting violence against the government he supposedly heads, there must be consequences. One lesson of history is that democracies must be willing to defend themselves. Letting would-be authoritarians walk away and try again only validates anti-democracy propaganda: that democracies are fundamentally weak, and that advocates of democracy secretly admire and envy the self-styled Leader and his followers for their love of country and the courage of their convictions. “If we got away with this,” the anti-democratic forces wonder, “what else can we get away with?”

So count me among those who approve of both these stories. But at the same time, I recognize that each offers our constitutional republic only a short-term salvation. The longer-term problem is the widespread perception that our system is not working, and that it grows more dysfunctional year by year. If Trump is convicted, American fascism might be stuffed back into its box for a few years. And if Biden uses his powers wisely, he may spark a short-term rise in the nation’s self-confidence. Certainly, he should be able to quickly reverse the corrosive effect of the last year, when our president appeared to have lost interest in a plague that killed (and continues to kill) thousands of Americans each day.

But long-term, the health of any democracy relies on public faith in one simple idea: The most effective and most legitimate way to seek change is to convince other citizens to agree with you, so that the public will elect a government that will achieve the changes you seek. Conversely, a democracy is in trouble if its citizens begin to see elections as empty spectacles that change nothing.

Legislative failure. In the past several cycles, Democrats and Republicans have each won wave elections that left the party in control of the presidency and both houses of Congress. But neither produced an FDR- or LBJ-like list of legislative accomplishments. Instead, each managed only one big thing: ObamaCare for the Democrats and the Trump tax cut for the Republicans.

In spite of broad support from their voters, the Democrats couldn’t pass cap-and-trade to fight climate change, ObamaCare’s public option, any significant gun control, or immigration reform. Republicans couldn’t repeal ObamaCare, pass an infrastructure program, or fund Trump’s wall.

Voters on both sides were left wondering: What was all that for?

Admittedly, both parties faced obstacles beyond the Senate filibuster. Obama thought he had more time: His filibuster-proof 60-Democrat Senate didn’t last two years, but only half a year; Republican lawsuits delayed Al Franken’s arrival in the Senate until July, and the next January the Democrats unexpectedly lost the Massachusetts seat vacated when Ted Kennedy died. (Only a parliamentary maneuver allowed ObamaCare to become law.)

Trump’s GOP suffered from a lack of real programs to pass. “Repeal and replace ObamaCare” turned out to be an empty slogan; neither Trump nor any other Republican had a replacement plan, and three Republican senators wouldn’t vote for repeal without one. Trump eventually announced an infrastructure plan, but couldn’t get his own party to buy into it.

Each party suffered from the implacable opposition of the other. It is striking to look back at big legislation of the past. Medicare got 70 votes in the Senate, including 13 Republicans. Social Security got 77 votes (16 Republicans), and the Voting Rights Act got 77 (30 Republicans; the main opposition came from Southern Democrats). The National Environmental Protection Act (which, among other things, established the EPA) passed unanimously. But both ObamaCare and the Trump tax cut were party-line votes.

In part, the polarization of the Senate is due to the polarization of the voters. But the polarization of each party’s special interests is also an important factor. Polls show considerable bipartisan support for giving some kind of legal status to the Dreamers (undocumented immigrants brought into the US as children, many of whom remember no other country), for simple gun-control measures like universal background checks, for limits on medical malpractice lawsuits, and a number of other measures. But base voters oppose them, and so do organizations like the NRA or the National Trial Lawyers. So they don’t pass, to the great frustration of the majority of Americans.

Issues that used to be negotiable have now been cast as matters of principle. Republicans cannot support any tax increase, no matter what concession they might get in exchange. Many Democrats draw a line in the sand on entitlement reform. As recently as 2013, the Senate could pass a bipartisan immigration reform bill. But today that bill (which might also have passed the House if Speaker Boehner had allowed a vote) seems like a relic from a bygone era.

But all these factors come back to how easy it is to block things in the Senate. In a polarized environment with powerful special interests, it’s hard to get 60 votes for even the most popular bills. One of the levers that previously induced senators to compromise was the argument: “This bill is going to pass anyway. You might as well get on board and see if you can win any concessions in exchange for your support.” (This still works for must-pass bills like the ones that keep the government open.) But if the bill is likely not going to pass, why risk the attack ads that a yes-vote might generate?

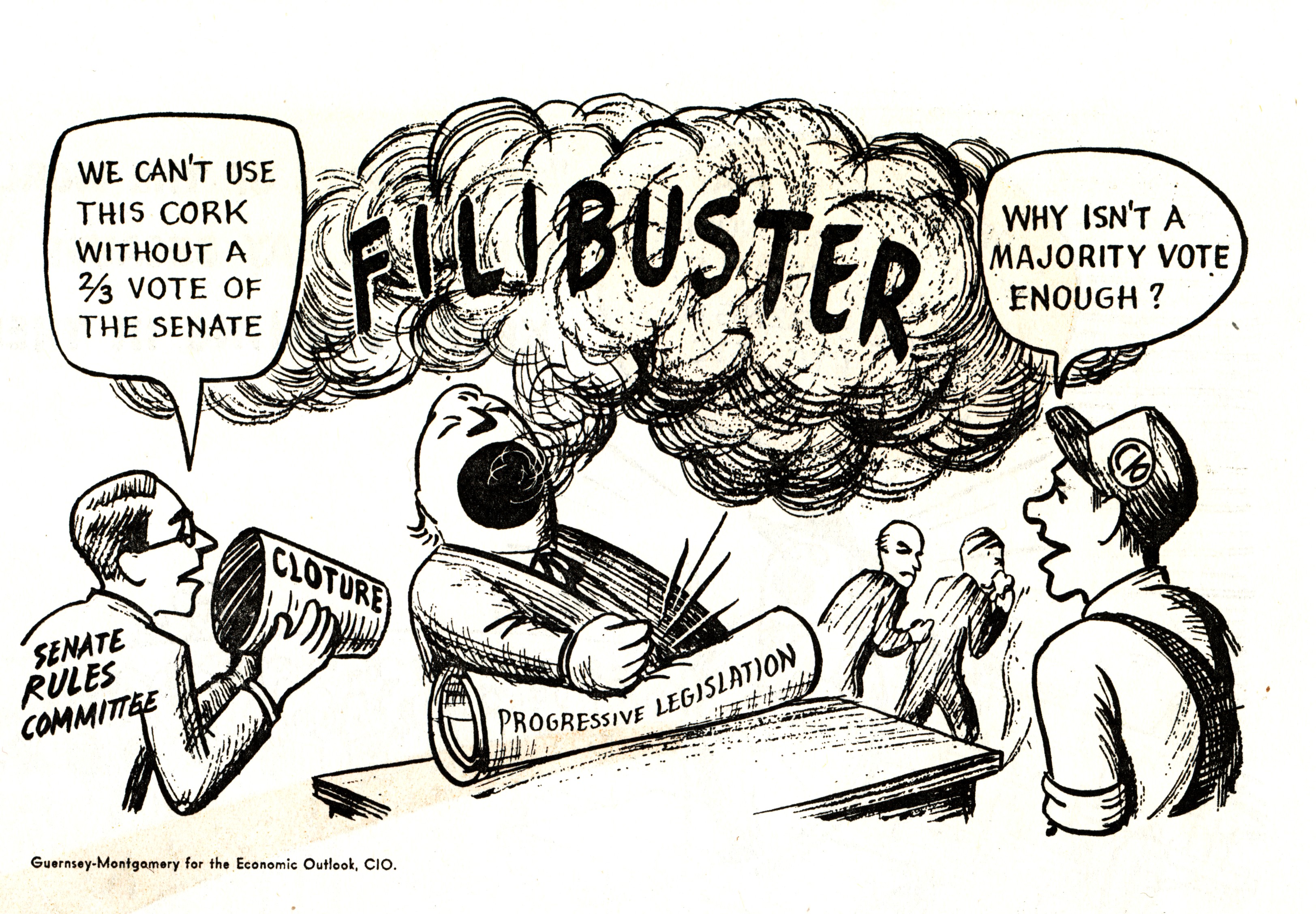

Filibusters have become the rule, not the exception. The filibuster has existed since a rule change in 1806, which is sometimes blamed on the villainous Aaron Burr. It is not in the Constitution. On the contrary, the Constitution explicitly requires Congress to have supermajorities only for a few highly significant actions: removing a President or other official via impeachment, passing a constitutional amendment, and ratifying a treaty. But the Founders never intended a supermajority requirement to apply to ordinary legislation. In Federalist #22, Alexander Hamilton railed against those who would ask for a supermajority provision:

The public business must, in some way or other, go forward. If a pertinacious minority can control the opinion of a majority, respecting the best mode of conducting it, the majority, in order that something may be done, must conform to the views of the minority; and thus the sense of the smaller number will overrule that of the greater, and give a tone to the national proceedings. Hence, tedious delays; continual negotiation and intrigue; contemptible compromises of the public good. And yet, in such a system, it is even happy when such compromises can take place: for upon some occasions things will not admit of accommodation; and then the measures of government must be injuriously suspended, or fatally defeated. It is often, by the impracticability of obtaining the concurrence of the necessary number of votes, kept in a state of inaction. Its situation must always savor of weakness, sometimes border upon anarchy.

… When the concurrence of a large number is required by the Constitution to the doing of any national act, we are apt to rest satisfied that all is safe, because nothing improper will be likely TO BE DONE, but we forget how much good may be prevented, and how much ill may be produced, by the power of hindering the doing what may be necessary, and of keeping affairs in the same unfavorable posture in which they may happen to stand at particular periods.

Filibusters were purely theoretical until the 1830s, and fairly rare thereafter. The Senate tended to think of itself as a gentlemen’s club; grinding business to a halt was ungentlemanly behavior. For years, filibusters were reserved for only the most important issues. For example, Southern senators used them to stifle civil-rights legislation, which they saw as a direct threat to the white supremacist society of the Jim Crow states. (Filibustering was, in essence, an alternative to seceding again.) But then the frequency of filibusters took off.

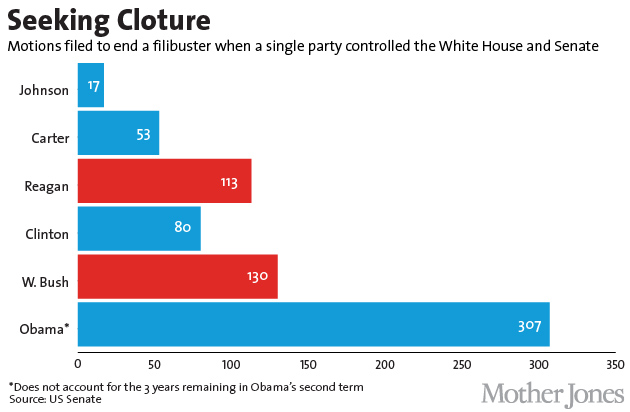

Today, the press simply takes for granted that everything will be filibustered, and routinely reports that it takes 60 votes to get anything through the Senate. For example, the post-Sandy-Hook-massacre effort to get background checks through the Senate failed 54-46, with the 54 voting for it. This was reported as if it were business as usual. Effectively, the Senate now has the supermajority requirement that Hamilton so opposed, with exactly the unfortunate results he predicted.

Spreading effects of Congressional dysfunction. People from both parties (or neither) frequently complain about two other unfortunate trends in American governance: the imperial presidency and the ever-expanding reach of the Supreme Court. Both of these developments are promoted by the dysfunction of Congress.

Increasingly, presidents push the boundaries of executive orders. It’s easy to criticize Trump’s excesses, like the phony emergency he declared in order to redirect money to his border wall. But it’s also instructive to note Obama’s overreaches, like DACA, which protected the Dreamers from deportation and allowed them to work legally, and the DAPA program that would have covered parents of American citizens if the Supreme Court had allowed it.

In Obama’s remarks announcing DACA, he pleaded for Congress to turn a popular cause into a law.

Now, let’s be clear — this is not amnesty, this is not immunity. This is not a path to citizenship. It’s not a permanent fix. This is a temporary stopgap measure that lets us focus our resources wisely while giving a degree of relief and hope to talented, driven, patriotic young people. … Precisely because this is temporary, Congress needs to act. There is still time for Congress to pass the DREAM Act this year, because these kids deserve to plan their lives in more than two-year increments. And we still need to pass comprehensive immigration reform that addresses our 21st century economic and security needs.

He stretched the power of executive orders because the American people supported something that Congress refused to do, or even bring to a vote. This is a common pattern in executive orders: Something needs to happen and Congress is log-jammed, so the president just does it on dubious authority.

Trump’s trade wars followed the same pattern. Tariffs are supposed to be set by Congress, but an obscure and seldom-used clause of a law delegated that power to the president under extreme circumstances. Trump decided those conditions were met and abused this power. But getting tougher on foreign imports was popular, so Congress did nothing to reclaim its prerogatives.

Much judicial overreach is similar. Take, for example, John Roberts’ rewrite of the Affordable Care Act. He was part of a conservative majority that ruled (wrongly, in my opinion) that the law’s insurance mandate couldn’t be justified by previous Supreme Court interpretations of the Constitution’s interstate commerce clause. Roberts, however, recognized that Congress has sweeping constitutional power to tax, so he reinterpreted the mandate’s penalty as a tax, allowing ObamaCare to stand.

In earlier eras, the Court might simply have voided the law, but delayed the implementation of its ruling to allow Congress to adjust. After a simple legislative fix — change the word “penalty” to “tax” — the program would have gone forward. But Roberts knew that in the current era, legislation only passes when the planets align. Voiding ObamaCare for any reason would have meant ending it for the foreseeable future. He wasn’t willing to be the reason why tens of millions of Americans lost their health insurance, so instead he rewrote the law himself.

A similar pattern accounts for the various administrative changes Obama made during the implementation of the ACA. It is common for big new programs to need fine tuning, because nothing complicated ever works exactly as its designers expect. In past eras, Congress would quickly pass such changes, recognizing that they improved an ongoing program. But ObamaCare’s opposition wanted to see it crash, and would not allow any legislative fine tuning. So Obama stretched his executive power to make the program work.

In the Founders’ vision, Congress is the vehicle for channeling public opinion into action. But that channel is blocked, so the other branches of government expand their power to compensate. This is not healthy for democracy: The expanding power of the president tilts us in the direction of an elected dictatorship, while the the Supreme Court’s extended range of action removes power from the political system entirely. But complete inaction in the face of well-recognized problems is also not healthy for democracy.

Stop the decay. The danger in this process should be obvious, because we see it happening all around us: People are becoming more cynical, and losing faith in the power of their vote. If passing, say, Medicare for All requires electing 60 Democratic senators, what’s the point of trying? Even expanding ObamaCare is more likely to happen via a Biden executive order than by an act of Congress. And if you oppose that executive power grab, you will look to the Supreme Court to save you, not Congress.

The filibuster is far from the only anti-democratic provision in our system. The Senate itself allows a collection of small states that represent far fewer than half the country to gain control. The Electoral College makes it possible for a minority to elect the president. Gerrymandering and voter suppression make the House undemocratic.

But the simplest and most direct way to restore the vitality of Congress is to end the filibuster. If you can convince enough people to agree with you to elect majorities in both houses, you should be able to get legislation passed. If that legislation turns out badly, a new majority should be able to get it repealed. That’s what makes elections meaningful.

If elections stop being meaningful, people will not stop seeking change. They’ll just have to promote it through undemocratic means. Eventually, a Caesar will come and sweep the whole jammed system aside. And the People will probably cheer, just as the People cheered Caesar.

Comments

Agreed 100% that the filibuster must go. Else all will be stalled by the Rs. Well reasoned and argued as usual by Mr. Mader.

After the filibuster goes, unblocking the Senate, it would be nice to have a rule that bills passed by one chamber must be brought to a vote in the other… if this had been in place in 2013, we would likely have immigration reform, as you noted.

I think we also need transferrable, instant runoff votes the way fairvote.org advocate them, and ideally also multi-member legislative districts next. And then… if we can reform that Constitutional compromise that is every-state-get-2-senators…

The requirement that every state get the same number of senators cannot be changed. Article 5 says “that no state, without its consent, shall be deprived of its equal suffrage in the Senate” so essentially any amendment to have unequal number of senators would have to be unanimous, which will never happen. It’s unclear if you could do amendments that strip the senate of its powers, so that it wouldn’t matter how many senators each state had. I think the one plausible action that could lessen the anti-democratic aspects of the senate is to vastly increase the number of Representatives. If you had 1000 (or more) Representatives, that would make the electoral college much less anti-democratic. This would only take a law, not an amendment.

Yup, that’s why I put it last. It would require a constitutional amendment, the others don’t.

I forgot to also mentiom the National Popular vote compact, but that is an interstates initiative that Congress doesn’t get involved in anyway

I think that the Senate Majority Leader should not have the sole power to decide which bills can be discussed by his dominion over what comes to the floor.

What if a bill were given to a subgroup of, say, 6 senators (3each party) to be sort of pre-triaged: Have some discussion of pros, cons, adjustments that might create compromise. That gap votes on whether to put it in line for the full body, or return it to sponsors w “Not at this time because…too many other bills more urgent, benefits of it very one-sided/single-issue, proposals too vague and need development…

Have the subgroup be pple w some interest in the focus of the bill but from varied regions. Subgroups named afresh for each bill.

A suggestion I’ve heard is to allow anonymous discharge petitions. A discharge petition in the House can bring a bill to the floor if a majority of representatives sign on. This never happens because the Speaker will take revenge on members of his/her party who sign it. But an anonymous petition could successfully release a bill that the Speaker has blocked.

Something similar could be implemented in the Senate.

There’s another thread here, in addition to the filibuster,

“But the polarization of each party’s *special interests* is also an important factor.”

“But base voters oppose them, and *so do organizations like the NRA or the National Trial Lawyers.* So they don’t pass, to the great frustration of the majority of Americans.”

“In a polarized environment with *powerful special interests,* it’s hard to get 60 votes for even the most popular bills.”

Do you see it? Money in politics.

Of course. But the filibuster gives money a lower hurdle to jump.

Vis-a-vis the Filibuster, I think Harry Reid got it exactly backwards when he removed the filibuster from court appointments. I firmly believe that lifetime appointments SHOULD require a supermajority. That way we will get much more centrist judges, as the radicals, both left and right, simply won’t get voted in. It is everyday legislation which should only require 51 votes.

As to bringing bills to the floor, there is a way around the Majority Leader’s obstinance. It is a “discharge petition.” Look it up.

In the current environment, I’m afraid we just wouldn’t replace judges at all. A supermajority provision would have to be coupled with something to empower the center rather than the fringes.

“Roberts, however, recognized that Congress has sweeping constitutional power to tax, so he reinterpreted the mandate’s penalty as a tax, allowing ObamaCare to stand.”

This is fine actually. The law isn’t a code that can be worked in your favor by pinging the right phrases. Whether something is a tax or a penalty is not a matter of the words the legislation uses but a matter of what the law does. Its for reasons like this that the court needs to exist, as otherwise the congress could write unconstitutional laws and call whatever aspect of them as a part of a power they do have. They could, for instance, say that you’re being taxed by allowing troops to say in your home. Those troops are not being “quartered” and so this does not trigger the provision in the bill of rights. Congress has the power to do this because its a “tax” and congress has the broad authority to tax. Except no, such a thing is ridiculous. Congress cannot just label things other things in order to avoid what they truly are. And tax penalties are common things that exist in plenty of situations and this structure is more or less uncontested. To rule that the mandate penalty wasn’t a tax would negate a huge portion of all currently written regulation.

Now, Roberts was wrong to consider the mandate unconstitutional as a penalty. The argument against, that it is dumb, is itself dumb*. The government has the power to do lots of dumb things but this does not mean that the government cannot do things. But he was right to say that the penalty was a tax and within the broad authority to tax.

*Specifically the “does the government have the power to make you purchase broccoli?” has the implied answer of “no because that is dumb” and then this is to extend to “does the government have the power to force you to buy insurance?” but the proper answer is “yes because the congress has the power to regulate commerce and that is a commercial regulation whether or not its dumb. Just as the congress has the power to implement a 100% tax because they have the power to tax they have the power to force you to purchase broccoli even if both are dumb”

I agree with everything in your comment except the beginning. I think a law should BOTH correspond to Congress’ constitutional power and call things by their proper names. If the mandate were only constitutional as a tax (which I agree is a mistaken interpretation), then I think it’s up to Congress to call it a tax.

I shared this and an astute friend commented as follows. I concur…

“Also, restore the Vice President as president of the Senate, and stop giving the majority leader absolute control over its proceedings.”

Per Article I, Section 3, the Consitution, the Vice President is the President of the Senate. Full stop. Previous Vice Presidents have deferred to the Majority Leader for day-to-day business because their presence was not usually required. Kamala Harris is no fool and I think, if election results had left the Senate with a one- or two-R majority, the President of the Senate would have chosen to preside and set the agenda instead of the Majority Leader. As it is, even with a 50-50 split, I suspect Vice President Harris will be much more active as Senate President than previous Vice Presidents have been.

This makes sense to me, but I can’t help thinking that if it worked, somebody would have used it by now. Why did Nixon let Mike Mansfield run the Senate rather than insisting Spiro Agnew do it?

Trackbacks

[…] This week’s featured posts are “The Orwellian Misuse of ‘Orwellian’” and “To Save Democracy, End the Filibuster“. […]

[…] I’ve discussed elsewhere, all the issues facing the Biden administration have a background theme: proving democracy still […]

[…] weeks ago, I wrote about why the Senate should abolish the filibuster. (My argument transcended any particular legislation that might get filibustered: If a tiny slice […]

[…] enters its sixth week, the action has shifted to Congress. Congress (as I have pointed out before) is the most dysfunctional branch of American government, and its weakness is the root cause the […]

[…] filibuster. Which brings us back to the filibuster. I already made my case for ending the filibuster back in January, so I won’t repeat it. The Democrats have the power to end the filibuster, […]

[…] the Supreme Court and it isn’t the Biden administration. As I’ve observed before, the dysfunction of Congress forces the other two branches to […]