The differences are less stark and less consequential than either the candidates or the pundits would have you believe.

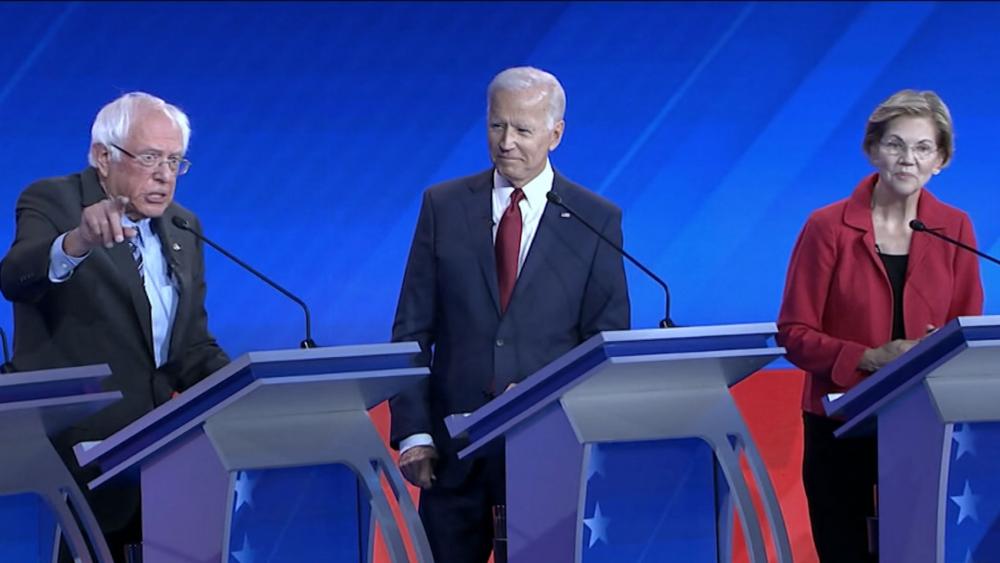

If you listened to the opening segment of Thursday’s Democratic debate, or the media discussion of it that followed, you might imagine that the ten candidates are sharply divided on healthcare. It’s easy to lose sight of the fact that the Democrats’ disagreements branch out from a fundamental agreement on two principles, both of which are wildly popular with the general public.

- When Americans get sick, they should get the care they need.

- Paying for needed care shouldn’t drive families into bankruptcy.

Republicans, by contrast, focus on cost rather than coverage, and plan to control costs by inducing money-conscious Americans to forego care. They envision a nation filled with people who over-use the healthcare system, and would do so even more if it weren’t so expensive (as if we all viewed a night in the ER as entertainment, and would happily schedule unnecessary colonoscopies just for kicks). And if those expenses result in hypertension patients trying to save money by doing without their prescriptions, or diabetics getting priced out of the insulin market … well, those are the sad-but-necessary results of keeping taxes low and profits high.

So the debate the Democrats are having, about how to achieve the twin goals of care without bankruptcy, just isn’t happening on the Republican side. [1] If you believe that sick Americans should get care that doesn’t bankrupt them, you should be a Democrat.

The debate. As you listen to the arguments among Democratic candidates, you need to bear that fundamental agreement in mind. The disagreements are all about how to achieve those goals: Go straight there with a massive expansion of Medicare to cover everyone, or move more gradually by adding a public option to ObamaCare? Replace the current private-insurance system (with its familiarity as well as its profiteering and inefficiency), or build on top of it?

The Trump administration, meanwhile, is backing a lawsuit that would declare ObamaCare unconstitutional and make all its provisions void. Insurance companies would once again be able drop coverage for people with preexisting conditions. [2]

Why the tax gotcha? One fundamental difference between Medicare-for-All and our current healthcare system is how it’s paid for: Many treatments that are currently paid for through premiums and co-pays would be paid by the government, i.e., through taxes. The taxes would be progressive, so the burden of payment would shift towards the wealthy.

I don’t fully understand why, but for some reason both the media and the candidates are treating this like a gotcha question: Interviewers are asking it in a challenging way and candidates are dodging it. I’m not sure why it’s so hard to say, “Payments you used to make through premiums and co-pays, you’ll now make through taxes, and unless you’re very rich you’ll probably pay a lot less.” If I were an MfA candidate, I’d back that up with a pledge: “By the time Congress has to vote on a package, independent analysts will have weighed in on the costs. And if it doesn’t save middle class households a substantial amount of money, we won’t do it.”

That said, there is one group of people who will pay more: Those who could afford to buy health insurance, but have been successfully betting that they won’t get sick. They’ll have to pay something in taxes rather than the nothing in premiums that they’re paying now.

How it will play out. The MfA vs. public-option debate comes down to two points.

- The Medicare-for-All candidates (mainly Sanders and Warren) are right about efficiency. A universal healthcare system that covered everybody for everything would deliver better healthcare at a lower price than we’re paying now. That price would fall entirely on the government, so government spending would go up even as total healthcare spending went down.

- The public-option candidates, who want to let the private health insurance industry keep running, but give people the option of a Medicare-like system, are right about the politics. Rightly or wrongly, large swathes of the public don’t trust the federal government enough to bet everything on a big government program with no alternatives.

Warren was right to point out that no one loves their insurance company. (Mine is Aetna right now, and no, I don’t love it.) But I think a lot of people like the idea of having another choice if MfA turns out not to be as great as advertised.

The problem is that some of the gains a universal MfA would produce depend on the universality: Doctors would only need to know one system. Public health programs with diffuse benefits could be instituted without worrying exactly who is going to pay what when. The public option would still be more efficient than private insurance, but not as good as it could be.

In the end, though, this debate is not going to make a difference, at least in the short run. Even if Sanders or Warren get elected, together with a Democratic House and Senate, the new president will still find that the votes aren’t there for Medicare for All. As we saw with ObamaCare, the program will be whatever it needs to be to get the last few votes. In other words, even with Democratic majorities and the elimination of the Senate filibuster, it is the 50th Democratic senator and the 220th Democratic representative who will call the tune. They will be moderates from swing districts.

So one way or the other, the program will get scaled back to a public option. If that program is allowed to go forward without sabotage (as Trump has been sabotaging ObamaCare), the public option will gradually gain public trust, setting up an eventual universal program that may well resemble Medicare for All.

[1] Given the wide popularity of the two fundamental Democratic points — sick people should get care without going bankrupt — Republicans generally avoid detailed discussions of healthcare. Block whatever the Democrats want to do and repeal ObamaCare, and then something will happen that solves everybody’s problems.

That came clear in the repeal-and-replace debate in 2017. The replace part was always vaporware whose details could only emerge after repeal.

That scam is still going on. WaPo’s Paige Winfield Cunningham reports that the White House has given up on the health care plan it said it was writing, to be released only after the 2020 election. “The Republican Party will become the Party of Great Healthcare!” Trump tweeted back in March. He promised “a really great HealthCare Plan with far lower premiums (cost) & deductibles than ObamaCare. In other words it will be far less expensive & much more usable than ObamaCare.”

Cunningham notes that there is no sign anyone is working on this. Groups that you’d expect to lead the charge for a Republican plan, like FreedomWorks, say they haven’t been told anything about it.

The problem is that there’s no Republican consensus for a plan to implement. RomneyCare was the only healthcare plan the GOP had, and their idea-pantry has been empty ever since Obama used Romney’s plan as the basis for his proposal.

The usual Republican answer, the free market, is a non-starter here. Private health insurance companies make money by insuring people who don’t get sick. Given its freedom, no company would insure sick people.

[2] Trump claims to want coverage for preexisting conditions, but has put forward no plan for how that would happen. BuzzFeed summarizes:

The GOP argument is that Obamacare disappearing would be so catastrophic — regulated markets would collapse, millions of low-income people would lose Medicaid, insurers could once again deny coverage to people with preexisting conditions — that Congress would have no choice but to set aside their differences and pass a replacement.

We saw something similar play out with the Budget Control Act of 2011. Supposedly, the automatic budget cuts (the “sequester”) that would set in if Congress couldn’t come to an agreement were so onerous that of course Congress would come to an agreement. We’ve been dealing with the sequester ever since.

In general, if somebody’s plan is so onerous that it can only be announced in the face of an emergency, I want no part of it.

Comments

Just a bit of context to add on MfA vs public option if I may, Doug. For those of us health advocates who can remember that far back, the public option was dangled as bait by Obama in 2007/2008 before, like Lucy, Charlie Brown, and the football, it was abruptly taken off the table once he got in power. The move was maybe predictable by those who were following the money, but the point is we’ve been here before. I don’t think skepticism around the public option, especially coming from the establishment/status quo/conservative dems, is unreasonable given the history. It also goes back to the loaf/half a loaf issue. If you come to the bargaining table asking for only half a loaf, don’t be surprised when you get crumbs.

Full disclosure, I’d be fine if we end up with an opt-out public option. If you find an employer or insurance company that is offering better coverage at better prices, go for it. The efficiencies of MfA would make stiff competition, but stranger things have happened. I just don’t trust “centrist” democrats to lead us there and not pull the football back at the last minute.

Warren and Sanders tried to explain how taxes would rise, but with no premiums or copays, overall household expenditures would be lower under MfA. However, the details are important. Most people get their healthcare through their employer, who pays a portion of premiums. Take the example of someone whose employer pays $300 while they pay $200, plus $100 in copays. The total cost is $600, but from the worker’s standpoint, he only pays $300. If under MfA, the worker now pays $400 in new taxes, it’s going to feel like an increase, unless his employer now hands over the $300 premium they had been paying as a wage increase. If the employer just pockets the money, the worker won’t see much benefit to the change.

If this were written into the law, it would be very easy to sell if we tell people that yes, their taxes would go up, but so would their wages.

Another option would be for the laws to say that whatever a company currently contributes toward employee healthcare remains the same under the new law, but now it goes to MfA, rather than private insurance companies.

Except one goal of MfA is to get away from the current model where people get their health insurance through their employer. That system started when unions negotiated health insurance as a worker benefit in the 1950s.

I lived in the UK for 3 years. What most Americans don’t understand is that there are two parallel systems in operation there; the National Health Service, which provides free care to all (including most prescriptions), and private medical insurance, available to those who want it. There are doctors who accept only NHS patients, only private patients, or both. So instituting a single payer system doesn’t automatically mean the end of private insurance.

I’m surprised there’s no mention of the successful, efficient and popular national health plans in place for decades in Europe and elsewhere. Private plans are also availabe to people who want them.

Under Sanders’ plan, private insurance would be illegal. Everyone would be under the public plan, with no special perks for people who could afford to pay more.

Trackbacks

[…] This week’s featured post is “The Democratic Healthcare Debate“. […]