China either is already the world’s largest economy or soon will be. In order to compete for world leadership in the coming decades, the US will need to represent a community of like-minded nations, not go it alone.

America First. The foreign policy Donald Trump ran on came down to two words: “America First!”

He never spelled out exactly what policy agenda that slogan entailed — Trump 2016 was never the kind of campaign that constructed 12-point plans or posted white papers on its web site — but the attitude it expressed was clear: Both economically and militarily, the United States is the world’s 800-pound gorilla, and we need to start acting like it.

According to Trump’s populist critique, past administrations of both parties worried too much about principles like free trade and human rights, and invested too much of their hopes in multinational organizations like the UN, the WTO, and NATO. The Bushes and Clintons and Obama — and basically every president since Truman — tried to create a world of rules and mutual commitments, and failed to recognize something Trump finds obvious: Rules protect the weak. A world without rules is governed by the Law of the Jungle, and under that law the 800-pound gorilla always wins. That’s why he felt confident promising us “so much winning“.

To Trump and his followers, it makes no sense that the US has been trying to lead the world by setting a good example, rather than dominate it by telling other countries how things are going to work. It’s been crazy to keep our markets open when other countries close theirs, respect their intellectual property when they don’t respect ours, or extend our military shield over allies who don’t invest in their own armed forces the way we do. Our strength ought to get us a better deal, but it doesn’t because we keep volunteering to take a worse one.

So if it meant anything, “America First!” meant that it was high time we stopped volunteering to take the short end of the stick. Stop trying to create a world of rules that apply equally to everyone and stop averting our eyes when other countries cut corners. Instead, deal with every country one-on-one, a situation where our superior power will let us tell them what’s what. And what we will tell them is: “You need us more than we need you. So we win, you lose.”

During the campaign, examples of how Trump pictured this working would occasionally pop out: If we were going to liberate the Iraqi people from Saddam Hussein’s tyranny, we should have taken their oil to make it worth our while. If our military is going to keep defending Europe, they should pay us. Shortly after taking office he told the CIA the principle we ought to live by: “To the victor belong the spoils.”

Short-term and long-term. A year and a half into the Trump administration, we’re still waiting for those white papers and 12-point plans. (An anonymous staffer recently summed up the Trump Doctrine by expanding “America First!” from a two-word to a three-word slogan: “We’re America, bitch!“) But the outlines of a Trump foreign policy are starting to become clear: no TPP; no Paris Climate Accord; no Iran denuclearization deal; no UN Human Rights Council. We move our embassy to Jerusalem because we’ve taken Israel’s side, and aren’t trying to broker peace any more. We don’t accept other countries’ refugees. We insult our allies and leave them in the dark about our intentions. We can act like that because we’re America, bitch.

Once the Trump administration gets outside the restrictions of multinational agreements and into bilateral negotiations, it makes big demands and waits for other nations to back down, threatening terrible consequences if they don’t. Strangely, these tactics have yet to work anywhere. Mexico still isn’t paying for the wall and just elected a government more resistant to American pressure than ever. No one — not China, not Canada, not the EU — is knuckling under to our trade demands. North Korea gave us some pretty words, but doesn’t seem inclined to abandon its nukes.

Those problems, the administration assures us, are just short-term. As soon as other countries understand that we’re serious, they’ll realize who has the upper hand. Thursday night, Trump told a rally in Montana: “We’re going to win [the trade war with China] because we have all the cards.”

So far, that hasn’t been true: We hit them, they hit back — as if we were equals or something. But who knows? Maybe in the medium term Trump’s strategy works out. Maybe over the next year or so Canada and Mexico will decide that they do need to renegotiate NAFTA so that it tilts more in our favor. Maybe China and the EU will drop their reprisal tariffs and be content to let us buy less from them. Maybe we’ll get a new Iran deal that restricts their nuclear program for longer than Obama’s deal did, or adds provisions about ballistic missiles or exporting terrorism. Maybe the North Korea denuclearization agreement will turn into more than a handshake and a photo op.

I’d be surprised, but what do I know? Stranger things have happened.

But now let’s expand our time horizon and recognize one obvious fact: In the long run, it’s China who will be the world’s 800-pound gorilla. If the world is running according to the Law of the Jungle in 2030 or 2050, they win, not us.

How the US and China stack up. At the moment, China has around 1.4 billion people, about 1/6th of the world’s population and four times America’s. Per capita, it’s still a much poorer country than we are, but the national totals are starting to even out.

Depending on how you measure, China either has already overtaken us as the world’s largest economy or soon will. [1] It’s more-or-less inevitable: As Japan and South Korea and Singapore have shown, it’s much easier to bring your people up to a standard that some other nation has already achieved than to create an entirely new standard of wealth. So China’s GDP grows over 6% in a bad year, while ours grows 3% in a good year. [2] Over time that adds up. If China ever manages to achieve a per capita income that is just half of ours, its total economy will be twice as large. That will give it a leading role on the world stage.

Over time that adds up. If China ever manages to achieve a per capita income that is just half of ours, its total economy will be twice as large. That will give it a leading role on the world stage.

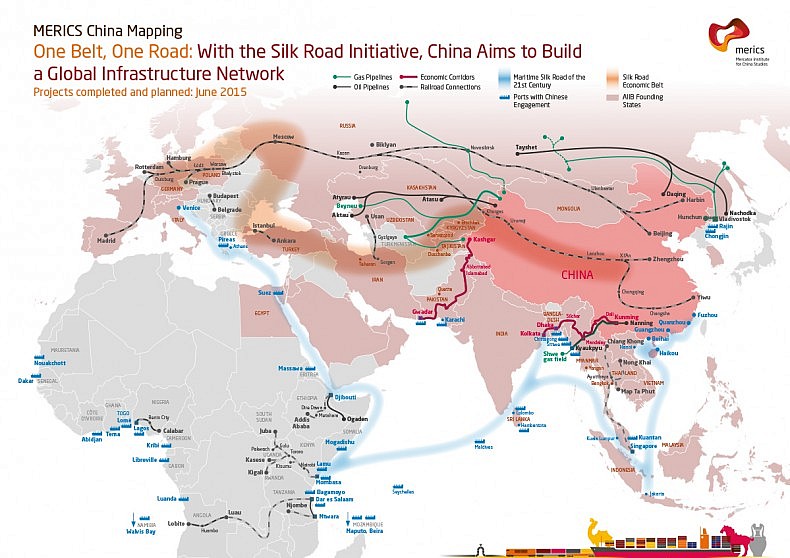

Already China is flexing its muscles in terms of soft power. Its Belt and Road Initiative is a multi-trillion-dollar plan to rebuild Eurasia’s infrastructure around China-centered trade routes and financial institutions.

Think about what this means diplomatically. China can approach Pakistan with its plan for a Pakistan-China Economic Corridor. What’s our vision for Pakistan? China foresees a high-speed-rail network that connects Shanghai to Singapore and Bangkok. What do we foresee?

It may not happen right away, but over time you have to expect China to exert the kind of world influence that comes with being the world’s largest economy. They will have the tax base to outstrip us in military spending eventually, if they choose to. Someday Shanghai or Hong Kong might replace New York as the world financial capital. Already, China can challenge us as a regional military power in Asia. Eventually it will have the resources, if it wants, to challenge us around world — at least if we are foolish enough to take them on by ourselves.

We need allies. We need institutions. In short, this is a uniquely bad time for the US to set up the world to be dominated by an 800-pound gorilla. Because before much longer, that gorilla won’t be us.

For the United States to continue to be the world’s most influential nation, we’re going to have to rely on two factors that Trump wants to turn his back on.

- We represent values that the world admires, not just our own money and power.

- We lead a community of nations who share those values.

If those two things are true, then America is the leading member of a coalition China won’t be able to bully for a very long time, or maybe ever: ourselves, the EU, Japan, the English-speaking parts of the British Commonwealth, South Korea, Taiwan, and maybe a few other countries. As India, Brazil, and other nations achieve relative economic equality with the countries in that coalition, there’s reason to hope that they will find it a club worth joining.

Whatever you may think of how the Trans-Pacific Partnership turned out in its final form, this was the geo-political vision that got it started: We would not negotiate trade with China by ourselves, but would get together with a large number of like-minded nations to write rules of the road. Long-term, we hoped that China might someday accept our rules in order to get the benefits of belonging to our club. There are many reasonable arguments against the TPP as it eventually was negotiated, but to scrap it and replace it with nothing will eventually prove to be a huge missed opportunity. (Pulling out of the WTO, which Trump is reported to be considering, would be even worse.)

Going forward, we want to live in a world of multinational institutions, because in a world of bilateral agreements, more and more it will be China who tells other nations how things are going to be.

The benefits of being a benign superpower. Since the end of World War II, the United States has been the chief promoter and protector of the international financial system. Trump and his followers see only the costs of this role and ignore all the ways that it has enhanced American power.

In the world today, the dollar is the international currency. National banks of almost all countries hold large reserves of dollars, and international trade is denominated in dollars. Just about any international transfer of money at some point passes through the US banking system.

What this means is that the market for dollars goes well beyond the needs of the US economy. The Federal Reserve creates dollars at zero cost, by entering numbers into its database. Many of those dollars go overseas eventually, and we get real goods in return: cars, iPhones, oil, steel, and Ivanka Trump’s fashion line. This is the seldom-discussed flip side of our trade deficit: We get away with running that deficit — consuming more than we produce — because the international economy needs a currency, and the dollar plays that role. The dollar is our chief export.

Similarly, US Treasury bills are the world’s default investment. This has allowed us to finance our budget deficit year after year, without suffering any of the ill effects that budget hawks are constantly predicting: Our national debt hasn’t caused inflation. The dollar’s value hasn’t collapsed. We don’t have to offer higher and higher interest rates to get investors to loan us money.

Short of military attack, the most potent weapon we can aim at an adversary is to cut them off from the US banking system. When fully enforced, that sanction can reduce another nation’s international trade to barter, and induce it to invent elaborate and expensive money-laundering schemes. The sanction that hurts Putin’s oligarchs most is the Magnitsky Act, which prevents sanctioned individuals from using the US banking system. The Atlantic explains:

What made Russian officialdom so mad about the Magnitsky Act is that it was the first time that there was some kind of roadblock to getting stolen money to safety. In Russia, after all, officers and bureaucrats could steal it again, the same way they had stolen it in the first place: a raid, an extortion racket, a crooked court case with forged documents—the possibilities are endless. Protecting the money meant getting it out of Russia. But what happens if you get it out of Russia and it’s frozen by Western authorities? What’s the point of stealing all that money if you can’t enjoy the Miami condo it bought you? What’s the point if you can’t use it to travel to the Côte d’Azur in luxury?

Once your wealth is expressed in dollars and recognized by the US banking system, you can take it anywhere and do anything you want with it. But otherwise, it’s barely money at all.

In a lot of ways, our banking power is better than military power. Unlike tanks or even nuclear missiles, our enemies have no answer for it. What are they going to threaten in return — to cut us off from the Russian or North Korean or Iranian banking system? Why would we care?

You might ask: How did we get power like this? Why do other nations let us keep it?

And the answer is that we have been entrusted with this kind of power because (for the most part) we have used it benignly. In theory, the other nations of the world could cut us out of the picture by deciding to use the yen or the Euro instead, or by getting together and creating a truly international currency and a truly international banking system to go with it. But the new currency would be like the Euro on a larger scale: negotiating and managing that new monetary system would be a huge headache, and who knows what holes and glitches it might develop? It’s just much more convenient for everybody to stick with the dollar and the US banking system, because our occasional abuses of that power have stayed within reasonable bounds.

In short, we have been fairly faithful stewards of other nations’ trust.

Or, translating the same idea into Trump-speak: We’ve been suckers. We haven’t put America first. We haven’t used every tool at our disposal to drive other nations to the wall and make them do what we want.

But that’s why other nations trusted us in the first place. And over time, we have benefited a great deal from that trust.

Bad timing. During this era, when we can see China gaining on us in the race for power (and in some areas already beginning to pass us), it’s tempting to try to squeeze all the juice we can out of our superpower status before we lose it. It’s also the worst strategic decision we could possibly make. At best, such a policy might produce a brief flare of American brilliance before our power winks out completely.

Now more than ever, the United States needs an international system based on principles and enforced by international institutions supported by multilateral agreements that all parties can live with and see benefit from. We need a system that isolates rogue nations and draws them into the rules-based community. We need to stand for universally attractive ideals like democracy, human rights, and opportunity for all. If China wants to compete with us for leadership, let it compete to lead the ideals-based coalition we have assembled. Let it compete to be a more admirable nation or a better steward of the world’s trust.

On the other hand, over the next five or ten years there might be some gains to cash in by becoming a rogue nation ourselves, flouting the principles we previously tried to establish, undercutting international cooperation on issues like global warming, and imposing win/lose agreements on weaker countries. The international institutions we helped design would likely wither, and to the extent they survived they would become alliances against our abuses of power. As we turned inward, other nations would as well, and the world as a whole would become a less prosperous place.

None of this would thwart China’s rise. And as the American Era ended, our legacy would not be an international system of mutually beneficial principles, rules, and institutions, but a Law-of-the-Jungle world, where the 800-pound gorilla always wins.

Unfortunately, that 800-pound gorilla would be China. China would owe us a great debt of gratitude for establishing a world system that allowed it to throw its weight around, dominating smaller nations (including us). However, I suspect China would never feel obligated to offer us anything to settle that debt. After all, gratitude is for suckers.

[1] If you google “countries ranked by GDP“, you’ll see lists from various international organizations that make it look like we still have a wide lead. For example: $19.4 trillion to $12.2 trillion in the World Bank list for 2017.

However lists like that are suspect for the following reason: They usually start by estimating a country’s annual GDP in the local currency, and then convert that estimate to dollars using the current exchange rates. But it’s widely suspected that China’s currency is undervalued; that’s what gives it such a big advantage in trade. Once you adjust for that undervaluation, you get very different numbers.

Economists argue about how to make that adjustment. One complex tool called “purchasing power index” says that the Chinese GDP really represents $21.4 trillion of purchasing power.

That’s calculation is hard for a non-economist to follow, but one quick-and-dirty (not to mention amusing) method for comparing the value of products across currencies is to use the Big Mac Index: Express all prices in units of locally produced Big Macs, which are assumed to be more-or-less identical around the world. (Example: If an iPhone 8 costs about $700 and a Big Mac sells for $3.50, an iPhone 8 costs 200 Big Macs.) At current exchange rates, you can buy 1.8 Chinese Big Macs for the price of 1 US Big Mac. So (adjusting everything by a factor of 1.8) annual Chinese GDP represents a number of Big Macs that would sell for around $22 trillion in the United States.

[2] In his 2012 campaign, Mitt Romney made the wildly optimistic prediction that his economic policies would lead to 4% growth. If Chinese growth got down to 4%, it would be a national emergency.

Comments

In:

summed up the Trump Doctrine by expanding “America First! from

I believe there is a missing double quotation mark after the exclamation point.

(Please feel free to delete this comment.)

Thanks.

Sadly it will be too late in hindsight to do anything about it. And DJT is so old that he won’t be around for us to squarely place the blame on him as the reason America loses out to China. (I just hate that we can’t rub his smug, stupid face in it.)

I’ve always proposed that the US needs to officially evolve our state of independence to interdependence, so this resonates.

Excellent article, Doug. I hope Trump is stopped before it is too late. Keeping all his idiotic election promises even though he was elected by a minority of voters. He’s doing so much damage, so much damage.

Could Russia (Putin-istan?) come to the same conclusion as Mr. Muder: they, too would be bullied by an 800 pound China. But I don’t see them trying to support a rules-based world order.

I’m no expert on Putin or Russia, but my impression is that they have a gangster mindset, which is necessarily short-term. I think Putin and the people around him envision a world where they steal a lot of money and get away with it, not where Putinism creates a thousand-year Reich.

I don’t know much, but I have picked up they are in relationship simply by proximity and leadership styles.

Doug, I think this article might be interesting to you: https://www.wikitribune.com/story/2018/07/05/asia/the-past-present-and-future-of-the-chinese-and-american-economies/77101/

It certainly caught my attention.

That is a good article. Could you figure out what the green lines on the last few graphs represented?

Yes, the BRI, China’s Belt and Road Initiative, is explained at: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/international/world-news/chinas-bri-initiative-hits-roadblock-in-7-countries-report/articleshow/63771550.cms

And in Saturday’s News, from Al Jazeera: https://www.aljazeera.com/programmes/countingthecost/2018/07/china-middle-east-xi-economic-charm-offensive-180714085057093.html

Trackbacks

[…] week’s featured post is “‘America First!’ means China wins.” I’ve been working on this piece for a few weeks and I’m pleased with it. Take a […]

[…] “America First!” means China wins […]