Republicans claimed that Obama’s deficits were apocalyptic, but trillion-dollar deficits are fine now that Trump is president. What’s the right level of concern?

In his 2008 stump speech, John McCain used to say that accusing Congress of spending money like a drunken sailor was an insult to drunken sailors. McCain is an old Navy man, the son and grandson of admirals, so he was particularly well positioned to take offense. The line usually got a good laugh.

Out-of-control debt and spending was a standard Republican complaint all through the Obama years. The Tea Party’s original claim to being non-partisan was that they also accused the Bush administration of being wild spenders, abetted by K-Street establishment Republicans as well as Democrats. For almost a decade now, Republicans of all stripes have railed against the deficit. Some dark curse would steal away our economic growth, their economists’ spreadsheet errors told us, if the total national debt ever got close to the annual GDP. As a result, Obama’s budgets turned into an annual game of chicken, the second round of stimulus spending never happened, infrastructure continued to decay, and we were stuck with a sluggish economy that didn’t get unemployment back under 5% until 2016.

But then the Electoral College appointed Trump president, and now the Bush days are back again: Deficits don’t matter. We can cut taxes and raise spending and everything should be fine (until the next Democratic president takes office, at which time the party will be over and the national debt will once again be an existential threat to the Republic). So Obama cut his inherited deficit in half, while Trump is in the process of pushing it back up again. The latest estimate of the FY 2019 deficit is $1.2 trillion, possibly rising to over $2 trillion by 2027. [1] And that doesn’t count the infrastructure plan that Trump plans to release today.

That’s been the pattern since Ronald Reagan: Republicans blow up the deficit, and then pressure Democrats to deal with it — which they’ve done. Presidents are inaugurated in January, inheriting a budget that started in October. Together, Clinton and Obama shaved more than a trillion dollars off the deficits of their entering year. But that was no match for the $1.7 trillion that Reagan and the two Bushes added to their entering deficits.

| President | entering deficit | exiting deficit | change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trump | -666 | ??? | ??? |

| Obama | -1413 | -666 | +747 |

| Bush II | +128 | -1413 | -1541 |

| Clinton | -255 | +128 | +383 |

| Bush I | -153 | -255 | -102 |

| Reagan | -79 | -153 | -74 |

(Numbers from thebalance.com. Negative numbers are deficits, the lone positive number a surplus.)

The GOP has never owned up to that pattern in its rhetoric, though. As Reagan was entering office, he scolded Congress about runaway debt.

Can we, who man the ship of state, deny it is somewhat out of control? Our national debt is approaching $1 trillion. A few weeks ago I called such a figure, a trillion dollars, incomprehensible, and I’ve been trying ever since to think of a way to illustrate how big a trillion really is. And the best I could come up with is that if you had a stack of thousand-dollar bills in your hand only 4 inches high, you’d be a millionaire. A trillion dollars would be a stack of thousand-dollar bills 67 miles high. The interest on the public debt this year we know will be over $90 billion, and unless we change the proposed spending for the fiscal year beginning October 1st, we’ll add another almost $80 billion to the debt.

So what did he do? He cut taxes, raised defense spending, and never ran an annual deficit less than $100 billion, peaking at $221 billion in FY 1986. In total, he added another $1.4 trillion to the national debt.

Trump is following the same script. In the short run, it’s good politics. Everybody likes a tax cut. If the increased spending means that the defense industry in your area starts hiring again, your local highways get resurfaced, or you don’t have to deal with cuts in Medicare, Social Security, CHIP, or whatever other government program your family relies on, then you’re happy. Compared to something immediate and personal, like whether you have a job or your kids can get the medical treatment they need, the federal deficit seems like an abstract, remote problem.

And yet, it’s hard to escape the nagging feeling that we can’t get something for nothing. If the government keeps spending and stops collecting taxes, it seems like something bad ought to happen eventually. But what?

Bad analogies. One problem we have in thinking about this question is that our national conversation about debt has been polluted by a really bad metaphor: The government’s budget is like your household budget.

The deficits-are-good-politics part of that analogy works. If you’re the budgeter in your household, and you suddenly decide that running up a big debt is no big deal, you can make everybody pretty happy for a while. The kids can get the Christmas presents they want. When nobody feels like cooking, the family can eat at a nice restaurant. That big vacation you’ve dreamed about can happen this summer rather than sometime in the indefinite future. If the job is getting to be too big a hassle, your spouse can just quit. It’s all good.

Until it’s not. Eventually, the household metaphor tells us, the bills will have to be paid, and then bankruptcy looms. And that’s where the analogy breaks down. Your household spending spree can’t go on forever, but it wouldn’t have to end if your bank simply cashed all your checks and never bothered you about the fact that your account is deep in the red. That’s the situation the U.S. government is in: The bank is the Federal Reserve, and it can (and will) simply honor all the checks the government writes.

Pushing the household analogy further, you might ask: But what happens when the bank runs out of money? In the case of the Fed, that can’t happen, because dollars are whatever the Fed says they are. For example, one of the ways the Fed dealt with the financial crisis that began in 2007 is called quantitative easing, which is defined like this:

Quantitative easing is a massive expansion of the open market operations of a central bank. It’s used to stimulate the economy by making it easier for businesses to borrow money. The bank buys securities from its member banks to add liquidity to capital markets. This has the same effect as increasing the money supply. In return, the central bank issues credit to the banks’ reserves to buy the securities. Where do central banks get the credit to purchase these assets? They simply create it out of thin air. Only central banks have this unique power.

Several countries’ central banks did this, but none more aggressively than the Fed, which created $2 trillion just by typing some numbers into its central computers. Since there’s no limit to the number of dollars the Fed can create this way, it can buy as many bonds as Congress wants to authorize. So there’s no limit to what the U.S. government can spend.

Consequently, anybody who talks about the U.S. government going bankrupt is just being hyperbolic. The government can refuse to cover its debts (that possibility is what the debt-ceiling crises of 2011 and 2013 were about), but it can’t be forced into bankruptcy. [2]

So what really goes wrong? You know something has to, because otherwise the government could just make us all rich.

The government’s debt gets financed in two different ways, and they correspond to the two things that can go wrong: high interest rates and inflation.

One way the debt gets financed is that investors buy government bonds. You may own some yourself, and if you have a 401k, probably some of that money is invested in mutual funds that own some government bonds. Banks or corporations with extra cash may hold it in the form of government bonds.

Investors like U.S. treasury bonds because they pay interest. But like every other market, the market for treasury bonds works by supply and demand. If the supply of bonds zooms up (because the government is borrowing more money), they won’t all get bought unless something attracts more investors. In this case, the “something” is higher interest rates. The more the government needs to borrow from investors, the higher the interest rate it will have to pay.

Since the U.S. government can’t go bankrupt, investors would rather loan to it than to just about anybody else. So the only way you or Bill Gates or General Motors can get a loan is to pay more interest rate than the going rate on treasury bonds. So the government borrowing more money can result in everybody paying higher interest rates: Your mortgage rate goes up, your credit-card rate goes up, businesses that want to borrow money to expand have to pay higher interest rates, and so on. If interest rates get high enough, people and businesses will stop borrowing, the ones who can’t cover the higher interest payments will go bankrupt, and the economy will fall into a recession.

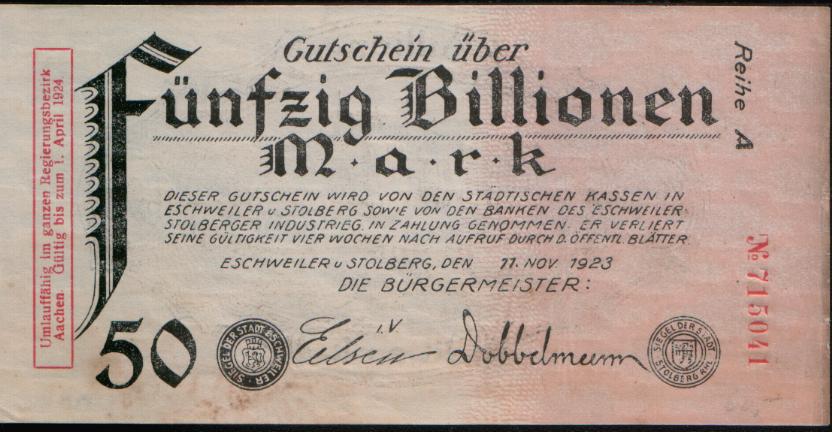

The 50-billion-mark note of 1923.

The other way the government deficit gets financed is that the Fed can buy the bonds itself, creating dollars out of thin air to do so. This is the modern-day analog of governments paying their bills by printing money, and it can have the same result as when the German government printed money in the 1920s: inflation. It makes sense: dollars are part of a supply-and-demand system too, so increasing the number of dollars should decrease how much each of them can buy. [3]

Except … Notice that I keep using words like can and should. What makes economics such a hard subject is that simple reasoning like this doesn’t always pan out. Sometimes when the Fed creates more money, the economy just soaks it up. If the economy has unused capacity — if, say, there are idle mines and factories, and unemployed workers who want jobs — the extra money might just bring all that back to life. If more people start working and spending, producing and consuming more goods and services, then the normal function of the economy requires more money. So the money the Fed creates might not cause inflation. And if investors are having trouble finding attractive alternative investments — as they do when economic prospects are iffy for everybody — they might be happy to loan the government more money without a higher interest rate.

In other words, sometimes there really is a free lunch. The government can borrow more money, make a bunch of people happy, and nothing bad happens.

That’s how things played out during the Obama years (and also during Reagan’s administration). The national debt went up substantially, the Fed created trillions of dollars, and yet both interest rates and inflation stayed low. (In Reagan’s case, interest rates were at record highs when he came into office, and went down from there.) Conservative deficit hawks kept predicting that the sky was about to fall on us, but it didn’t. [4]

What about now? The reason we got away with running such big deficits during the Obama years was that the economy was in really bad shape when he took office in 2009. Left to its own devices, the economy looked likely to go into a deflationary cycle, where money stops circulating and suddenly no one can pay their debts: Businesses go bankrupt, so workers lose their jobs and creditors don’t get paid. That causes them to go bankrupt, and the whole vicious cycle builds on itself.

Classic Keynesian economic theory says that the government should run deficits during busts and surpluses during booms. [5] That way the overall debt stays under control and the economy grows without violent swings up and down. That’s what the record $1.4 trillion deficit in FY 2009 (the Bush/Obama transition year) was for: It provided some inflationary pressure to balance the deflationary pressure of the Great Recession. The government played its Keynesian role as the spender of last resort, and so money kept flowing. Without that stimulus, things could have been much worse.

But the situation right now is very different. For the last several months, the unemployment rate has been 4.1%, the lowest it has been since the Goldilocks years of the Clinton administration. We’ve never run a trillion-dollar deficit during a time of economic growth and low unemployment, but we’re about to.

In this situation, we’re unlikely to get the free lunch. The free lunch happens because productive capacity is just sitting there, waiting for new money to bring it to life. If you need more workers, you don’t have to hire them away from somebody else, you can hire them off the unemployment line. When a business increases its orders, its suppliers don’t have to build new plants or pay overtime, they just start running their factories on their regular schedules rather than at a reduced rate.

When the economy is already humming, though, all the increased inputs come at a higher cost. Somewhere there are going to be bottlenecks, places where supply can’t be increased easily, and so that limited supply will go to the highest bidder at an increased cost. Those price increases ripple through the system, and you have inflation.

Inflation hasn’t shown up yet, though interest rates have already started to rise. Back in September, when passing a tax cut still seemed unlikely, rates on the 10-year treasury bond were barely over 2%. Now they’re a little under 3%. The stock market doesn’t submit to interviews, so no one can say exactly why the Dow Jones Index dropped 2800 points in 9 business days. But traders are often citing worries about inflation and interest rates.

Only hindsight will be able to tell us whether the markets are over-reacting. But there is a limit to how much debt the government can pile up without bringing on inflation and high interest rates. We just don’t know what it is.

[1] The last $400 billion on that estimate (the white box in the chart) comes from two temporary changes that Republicans assure us they intend to be permanent: the part of the recent tax bill that benefits individuals and some taxes that were part of the Affordable Care Act that have since be delayed. So Republicans can claim the deficit will only (!) be $1.7 trillion in 2027 if they admit that the long-term tax cut was really just intended for corporations.

[2] Somebody out there is asking: “What about Greece?” During the last decade, the Greek government has had a series of major financial crises that revolved around not being able to finance its national debt. Why won’t that happen to us?

The difference is that Greece doesn’t have a true central bank that controls its own currency. Greece is part of the euro-zone, so when it runs a deficit, it needs to borrow euros. Euros are controlled by the European Central Bank, a pan-European institution that feels no obligation to buy the Greek government’s bonds.

[3] That’s what goes wrong with the government making us all millionaires. The first thing you’d probably do if you became a millionaire is hire somebody to do some cleaning. But the people you’d be trying to hire are now millionaires too, so they’re not going to work for the same rate you’d have paid them before.

In addition to what I’ve described, inflation and interest rates can also interact: If investors expect the dollars they’ll be repaid in the future to be worth less than the dollars they’re loaning out now, they’ll want a higher interest rate to make up the difference. The value of the dollar in other currencies also comes into play: Inflation pushes the value of the dollar down, while higher interest rates prop it up. Things get complicated.

[4] The showdown that led to the 2011 debt-ceiling crisis was foreshadowed by Paul Ryan’s report “The Path to Prosperity“, which called for drastic reductions in government spending.

Government at all levels is mired in debt. Mismanagement and overspending have left the nation on the brink of bankruptcy.

[5] In 1937, John Maynard Keynes wrote: “The boom, not the slump, is the right time for austerity at the Treasury.” In actual practice, we’ve usually run big deficits during busts and smaller deficits during booms. But the overall principle is the same.

Comments

Great summary of difficult subject! I studied 3-4 years of economics, some of it working toward an MBA, which I never attained. I have always wondered why so much of political commentary is so ignorant of economics. I tell people to sign up for basic econ at their community college, but this isn’t quite the right thing.

When I lived in Peoria IL, Bradley U had received a grant providing for clergy to meet with econ profs for two days each year! Bradley then established a “center for economic education,” and provides a continuing ed course entitled “economic education” — “Specific contents arranged to meet the needs of the participants: elementary, secondary, and college teachers, clergy, public administrators, and other professionals. May be repeated up to 12 hours each.” This needs to be replicated at every college and university! (One problem was domination by a right-wing economist influenced by Friedman and Hayek!)

As a liberal arts major, I too studied some economics in college out of a desire to at least be able to tell the difference between honest economic analysis and self-serving economic lies. The effort was essentially useless; if you want a devastating account of the uselessness of mainstream economics read Steve Keen’s “Debunking Economics”.

What did clarify many things was discovering what money actually is, how and why it is created, and how it functions in the economy–its effects on inflation, unemployment, boom and bust cycles, and the actual consequences of deficits and/or surpluses.

If you don’t understand money you don’t understand economics, and if you don’t understand economics then people who can convince you that they do will take advantage of your ignorance.

One quibble; Germany’s hyperinflation was not “caused by” money printing.

Germany was obliged to pay war reparations in gold to the Allies after WWI. Germany’s mines were incapable of producing gold (no blood in that turnip) and it’s economy, devastated by war and depression, was incapable of producing a trade surplus. That left money printing as the only way to buy gold to pay the reparations. That was obviously not going to work, and it didn’t.

“That’s what goes wrong with the government making us all millionaires. The first thing you’d probably do if you became a millionaire is hire somebody to do some cleaning. But the people you’d be trying to hire are now millionaires too, so they’re not going to work for the same rate you’d have paid them before.”

Lots of people work for reasons other than money. I’d think a blogger would know that! 😉

Cleaning houses isn’t something you would do for something other than money!

I took that to mean slavery etc rather than the more pleasant options. Once someone has even their wanton needs met unpleasant jobs will not be worthwhile.

I am an economist so i can shed some light on these subjects if you with (though it was not my area of focus). However you did say one thing here and its important to note why this is the case

“And that’s where the analogy breaks down. Your household spending spree can’t go on forever, but it wouldn’t have to end if your bank simply cashed all your checks and never bothered you about the fact that your account is deep in the red.”

The reason the analogy breaks down its because countries don’t die. A person goes to the bank and gets a loan, they work for 40 more years paying off the loan and then their income stops. Either they stop working or they die. Banks know this and stop lending to people as they get older unless they can show income and assets. For a person the limit on the amount of money they can loan is the net present value of their future disposable income. This value decreases as you get older until it is zero because you’re dead. Banks have to be paid back by then.

But countries cannot die*. 40 years after the loan goes out they just keep on making income (taxes), 40 years after that they’re still making income. Countries can continue to operate in the red so long as its still possible to balance. Banks will still lend up to the limit of the net present value of future disposable income but this value could be hilariously large (and increasing) or even infinite. Currently a 20 year bond is 3% and inflation is 1.8%. So the sum of future income for the United States would be 85.3 times larger than the current tax base so call it 28 times GDP. And it doesn’t get smaller as time goes on, it just goes right on ticking; the debt never needs to go down.

So what breaks a county isn’t defined on the same types of limits that break people and doesn’t suffer the same dynamics even if it does exist.

*Well they can, but if they do your money is worthless anyway so might as well have lent it

I’d love to see your thoughts about the fact that our entire economic model is based on continual growth. Do you see any way for that to work on a finite planet? If so, how? If not, what should replace it?

There is nothing wrong with the assumption of continual growth and the economic model is not built on it. It is generally a fine assumption that people will continue to get better at making things and that things will accumulate if we continue to do so. And, at the very least, that inflation can be handled to create nominal growth if the situation calls for it. The complaints about “requirements for continual growth” are misplaced, a misunderstanding of what economic models do and what growth is. Economic models assume perpetual growth because that is all we have known and because we don’t have a good way to predict what growth will actually be.

While finite resources are an issue there is nothing preventing us besides our hubris and entrenched interests from moving away from them. These are political problems rather than economic ones. With zero population growth there will still be perpetual real growth.

Moreover, in the absence of continual growth the problems we’re going to be having is not those that relate to the relative quality of our economic models.

Thanks for your response! Can you point me at any additional information? The arguments I’m familiar with basically say that because resources are limited, economic growth can’t continue indefinitely and so working in a paradigm that uses economic growth as a primary benchmark of whether the system is working well will eventually lead us into catastrophe. That has always made intuitive sense to me, but if I’m missing something I’d like to know more.

I sort of agree with DMoses, but lack his certainty. Mainly, I’m not convinced by the argument that unbounded economic growth necessarily implies unbounded use of physical resources (which is impossible). So much of what we “consume” these days is already ephemeral, like entertainment or information.

I’ve seen the argument about ephemeral consumption before, and I think it makes sense, but only up to a point. If the economic growth is tied to populations growth, having everyone be healthy and comfortable will require more physical resources. Entertainment and information have an ephemeral aspect in that access to them can be multiplied cheaply, but there are still the costs of producing the entertainment and information (personnel, tools and props, recording devices, etc) and of distributing it (server space, personal electronics, etc). I haven’t seen any detailed analyses of how ephemeral consumption changes our real use of resources.

I think population growth is a separate issue. Sustaining a person is always going to take some minimum amount of physical resources, so there must be some limit on the population the planet will support. But I don’t think that economic models necessarily depend on population growth.

As physical resources begin to run out, they become more expensive, and there’s an incentive to replace practices that use a lot of them with practices that use less. I can already see that in my wife’s job. She used to travel a lot, but now she attends a lot of “meetings” that happen by video-conferencing.

All this analysis assumes the US will always be able to borrow in dollars. If our accumulated debt gets high enough, might lenders require loans in a currency they trust more, such as euros?

I think that gets back to where the household metaphor breaks down. Even if it gets to where nobody wants to buy US bonds denominated in dollars at any reasonable interest rate, “The other way the government deficit gets financed is that the Fed can buy the bonds itself, creating dollars out of thin air to do so.” It’s always possible to “borrow” dollars that way: since dollars are created and defined by the US government in the first place, it can always just create and spend more of them, at risk of inflation if it does toooo much of that. If you have your own currency you don’t need to find someone else to lend you that currency.

I was about to say what Daniel said. The real breakdown would come much further down the line, when ordinary Americans stopped accepting dollars in exchange for their work. And that’s a very extreme event. Even when it took wheelbarrows of marks to buy a loaf of bread, you could still buy a loaf of bread with marks.

But won’t Republicans just hand wave this all away by claiming that the tax cut will (more than) pay for itself and the deficit will then shrink all on its own? I mean it’s BS, but isn’t that what they would say in response to this article?

Some do say this, of course. But ultimately there is a reality. We get to the end of a fiscal year and the books balance however they do. It’s important to keep pointing at the history: They make the same claim every time, and it never pans out in the results.

When people are so attached to their ideology that reality doesn’t matter, you can’t reach them. That’s not the point of an article like this. The point is to hope that such people are nowhere near a majority, and to do what we can to keep well-intentioned people from being fooled by them.

This seems like a appropriate place to provide a link to the Samantha Bee segment “Speaking Of Cutting Taxes For The Rich”

They talk to several economists, including Paul Krugman, and are both informative and funny.

Sorry wrong link. Here’s the right one. (The other one is funny, but has nothing to do with economics.)

Trackbacks

[…] This week’s featured post is “Does the Exploding Federal Deficit Matter?” […]

[…] Does the Exploding Federal Deficit Matter? […]