Changing presidents or even changing minds isn’t enough. A real revolution has to change a lot of people’s political identities.

Some years ago, I was at a restaurant a couple blocks from my apartment when that cycle’s Democratic congressional candidate (Katrina Swett, which would make the year 2002) came in to campaign. It was late enough that most of the lunch traffic had left already, so shaking every hand in the room didn’t take her very long.

After the candidate left, our waitress — a pleasant young woman who had been doing a perfectly fine job as far as I and my friend were concerned — came over with an inquisitive look on her face. I thought she was going to ask us whether we knew anything about Swett, and whether she would be a good person to represent us in Washington. Instead, she asked whether we knew anything about Congress. “Is it, like, important or something?”

I’m not particularly good at answering a fundamental question when I was expecting a specific one, so let’s just say that I doubt my pearls of wisdom changed her life, or even that she remembers me at all. But I’ve remembered her ever since.

By telling this story, I don’t mean to denigrate the political sophistication of young adults or the working class or women or any other category that this waitress coincidentally belonged to. But to me, she represents a group that pundits and armchair political strategists often forget: people who just don’t care about politics. They aren’t stupid or any more self-centered than the rest of us, and they aren’t discouraged or embittered or angry. They just look at politics the way other people might look at football or fashion or Game of Thrones: They have never bothered to pay attention to it, and they don’t see that they’re missing out on anything.

It’s hard to say exactly how many such people there are. But certainly they could constitute a significant voting bloc, if they saw any point in it.

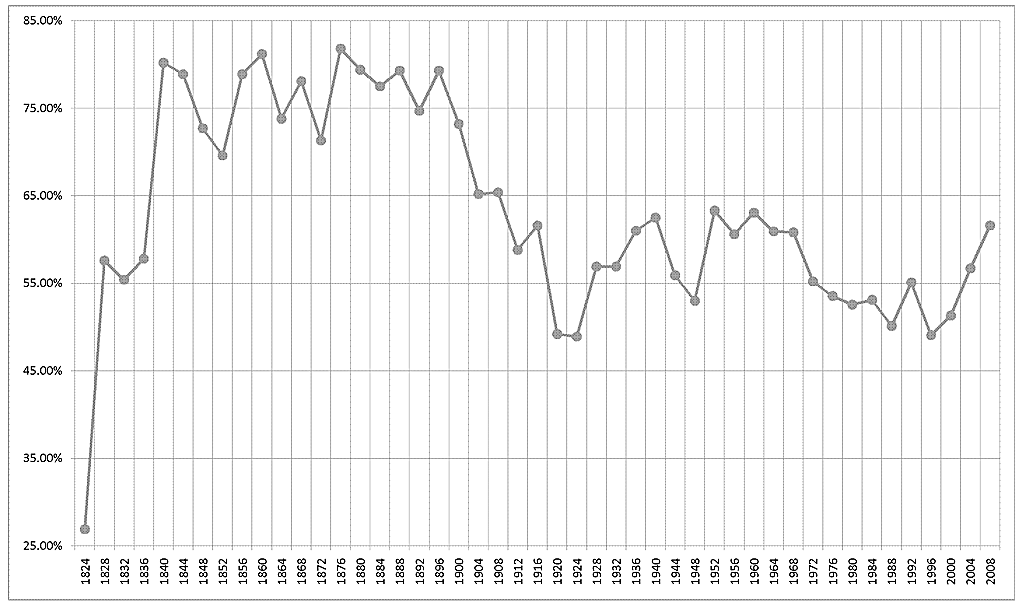

The truly silent majority. In a typical presidential election, voter turnout is somewhere between half and two-thirds of the voting-age population. Mid-term congressional elections usually draw less than half of the electorate, and less than a third bother to participate in some state and local elections. (A shade over 30% voted in Kentucky’s recent gubernatorial election, yielding a surprise Republican win.) As you can see from this graph of the turnout in every presidential election since 1824, this phenomenon is nothing new; to see significantly larger turnout, you have to go back to 1900.

So in virtually every contested election in the entire country for the last century, the margin of victory has been less than the number of people who didn’t vote. That massive lack of participation provides a blank wall onto which many people can project their conflicting fantasies.

The last election, 2012, 54 million evangelicals stayed home. Fifty-four million. Is it any wonder the federal government is waging a war on life, on marriage, on religious liberty, when Christians are staying home and our leaders are being elected by nonbelievers?

“Imagine instead,” he told the students at Liberty University, “millions of people of faith all across America coming out to the polls and voting our values.”

Real Clear Politics’ election analyst Sean Trende attributed Mitt Romney’s 2012 loss to “the missing white voters“, and argued that the GOP wouldn’t have to work so hard at appealing to Hispanics if it could just raise white turnout.

Wherever you stand on the political spectrum, you can imagine that the apathetic masses only appear not to care about public affairs. Actually, they just haven’t heard the right motivating message: your message. As soon as they do, then everything will start to change.

Heck, some version of this thought pattern occurs even in the fringiest, most radical circles. The armed yahoos who took over that wildlife refuge in Oregon didn’t figure on overpowering the federal government by themselves. They imagined a nation full of anti-government patriots, ready to take up arms as soon as someone was brave enough to sound the clarion call.

When they sounded that call and only a few dozen wackos showed up, I imagine they were pretty surprised.

The discouraged liberal majority. In spite of the daydreams of militiamen and social conservatives, the statistics say that marginal voters trend Democratic. That’s why relatively high-turnout elections like Obama’s first presidential race in 2008 (57.1% of voting-age citizens participated; that would be a low turnout in a lot of other democracies) are good for Democrats, while low-turnout elections, like the midterms in 2010 (41%) and 2014 (36%), strongly favor Republicans. That’s also why Republicans like to make voters jump through hoops: They believe the ones who won’t bother will mostly be Democrats.

Those numbers justify the Great Democratic Turnout Fantasy: If everybody voted, Democrats would win every election, everywhere. The Democratic advantage would be so insurmountable that the Party wouldn’t have to compromise on wedge issues like abortion or gay rights or gun control. Democrats wouldn’t have to pander to powerful interests or rich individuals. They could put the unalloyed New Deal/Great Society message out there and wait for the votes to roll in.

In particular, what if all the young people voted? What if all the women voted? What if all the low-wage workers voted? But we’re zeroing in on my waitress, and that should make us all stop and think: Who are the people who don’t vote, and what level of participation can we reasonably expect out of them?

Levels of engagement. People relate to politics in all sorts of different ways, and devote different levels of energy to it. Here’s a rough categorization, varying according to the depth and quantity of the thought and effort involved.

- Apostles. These are people who have a political worldview and can lay out their political philosophy — liberal, conservative, anarchist, communist, white supremacist, or whatever. They can state their principles and apply them to whatever issues come up, without any outside guidance.

- Activists. Some cause — anything from the environment or abortion to something as local as establishing a new park or putting a stoplight on a dangerous corner — got them interested in politics. Their interest in that issue placed them on one side or the other of our deep political polarization, so they have come to identify with other activists on a wide range of issues.

- Players. Like a sports team, a political party can be part of a personal identity; issues are just opportunities to argue that your team should win. For example: From the end of Reconstruction to the New Deal, the South was solidly Democratic. That wasn’t because the Democratic Party represented a philosophy universally accepted by Southerners. Rather, the Republicans were the party of Yankee invaders (and disenfranchised Negroes), so the Democrats were the home team.

- Fans. Left to their own devices, many people wouldn’t care about elections. But personal identity connects them to people who do care. When election day gets close, they look to a family member, a minister, a union leader, or some admired public figure to tell them who the good guys are.

- Impulse voters. These citizens have only a tangential connection to politics. They might not vote, or they might vote for some whimsical reason: They like or dislike a candidate’s face (or, more ominously, race or gender). Or they heard a story that made him/her look good or bad. Or a slogan appealed to them; maybe “Yes We Can” in one election and “Taxed Enough Already” in the next.

- The alienated. Disinterest in politics can also be part of a personal identity. Politics is some stupid thing that people yell at each other about. Politicians are like televangelists or get-rich-quick swindlers: They’re in it for themselves, and if you pay any attention to them at all you’re just being a sucker.

Most public discussion of politics comes from apostles or activists, and tends to project that level of interest onto non-voters: People don’t vote because the major parties aren’t addressing their issues or speaking to their philosophy. If only we changed our platform or the emphasis of our rhetoric, they’d flock to us.

But I don’t think my waitress had a political agenda in mind, or was turned off when Candidate Swett didn’t speak to it. I believe she was in the low-engagement impulse/alienated region, and honestly had no idea why she should care who went to Congress.

Paradoxes. When you picture non-voters as disgruntled apostles and activists, the world seems full of mysteries: What’s the matter with Kansas? Why do so many working-class whites vote against their economic interests? Why do so many Catholic Hispanics vote for pro-choice Democrats? How can the country whipsaw from a Democratic landslide in 2008 to a Republican landslide in 2010, and then re-elect Obama in 2012?

But while some apostles and activists don’t vote (holding out for a candidate with the proper Chomskyan or Hayekian analysis, I suppose), I believe that the vast majority of non-voters are in the low-engagement categories. You can’t understand turnout without accounting for them.

What’s the matter with the working-class whites? Thomas Frank’s book tells you, if you read carefully: As union membership declined, players and fans who used to identify with their unions (and vote that way) started identifying with their fundamentalist churches (and voting the other way).

Why does the immigration issue worry the Republican establishment so much that they want to pull against their base? Because they see Hispanics developing a team identity and deciding that the Democrats are on their side. If that happens, a lot of impulse and alienated Hispanics (and Asians and Muslims, for similar reasons) will become reliable Democratic players and fans, regardless of other issues.

What happened between 2008 and 2010? Liberal apostles and activists will tell you that Obama betrayed their high ideals. He failed to be the transformational FDR-like leader they had hoped for, and so the excitement they generated in 2008 was gone by 2010. But that should lead to another question: Why didn’t 2010 see a progressive wave similar to the Trump/Cruz/Carson rebellion we’re seeing on the right this year? Why didn’t all the disappointed liberals of 2008 send a more liberal Congress to Washington in 2010, one that would force Obama to come through on the hopes he had raised in 2008?

My answer is that the 2008 wave wasn’t primarily ideological or issue-based. While he presented well-defined positions on major issues and had the support of many thoughtful people, Obama also brought a lot of impulse and alienated voters to the polls on the strength of his personal charm, the Bush administration’s failures, and a message that resonated at a level not much deeper than “Hope and Change”. In 2008, Obama represented not just national health care and ending the Iraq War, but something he could not possibly have delivered: a “new tone in Washington” where politicians would start working together rather than yelling at each other.

Do I wish Obama had pushed harder on progressive issues (the way he started doing after 2014, when he had no more elections to face)? Yes, I do. But do I think he could have turned the 2008 coalition into a permanent electoral force that would have transformed American politics the way FDR did? No. I think that reading of recent political history is unrealistic, because the transformation Obama was supposed to catalyze depended on alienated and impulse voters suddenly deciding to change their personal identities and see themselves progressive activists and apostles.

Why would they have done that?

The kind of political revolution we won’t have. My rough categorization has fluid boundaries. At any given moment, people are migrating in both directions across the border between the alienated and impulse voters. Fans are getting energized and becoming players, while players are getting burned by their experiences and retreating back into fandom. Disengaged people are running into some issue that hits them on a deep level and makes them dig into politics in a way they never thought they would.

But (absent some huge crisis I don’t want to wish for) big changes in the personal identities of large groups of people don’t happen overnight. In particular, they don’t happen in one election cycle. So the vision of “political revolution” that I’m hearing from a lot of Sanders supporters (though Bernie’s own use of the phrase seems a little more cautious, if a bit vague) is not going to happen: We’re not going to sweep Bernie into office and then hold that majority together as a pressure group that will either make Congress pass his agenda, or toss them out of office in 2018 if they don’t. If we get a 2008-like progressive vote in 2016, a lot of that total will be low-engagement voters who will already have lost interest by Inauguration Day.

Change in America has never happened in a single election, through the election of a radical leader. The abolition movement, for example, didn’t start by sweeping Abraham Lincoln into office. It was a long, hard grind that began decades before Lincoln’s campaign. [1]

How big changes happen. When you look at American politics on a larger timescale, though, it does include a few big changes and re-alignments: the 1776 Revolution, abolition, the turn-of-the-century Progressive movement, the New Deal, civil rights, and the conservative counter-revolution we’ve been living in since the Reagan administration.

But none of those turnarounds happened quickly. Take civil rights: The Democratic Convention of 1948 split over civil rights, and Truman won without the break-away Dixiecrats. But the Voting Rights Act didn’t pass until 1965.

Ronald Reagan made it to the White House in 1980 on his third attempt, after failing to get the Republican nomination in 1968 and 1976. Republicans didn’t get control of the House until the Gingrich wave of 1994.

Between 1968 and 1994, a lot happened outside of electoral politics: Starting in the 1970s, billionaires and big corporations pooled their resources to create the intellectual infrastructure to make conservatism respectable. [2] Economic conservatives made common cause with religious fundamentalists; combined with union-busting, that instituted a shift in the way Americans found their political teams. Spin doctors developed ways to appeal to white racism covertly, without setting off a backlash. [3] Conservatives developed talk radio, then Fox News and a whole media counter-culture, with its own celebrities and cult identity. [4]

The next turning point. By now, the Reagan counter-revolution has gotten long in the tooth, and its plutocratic nature gets harder and harder to deny. If you look at inequality graphs, things started going wrong for the middle class after the Democrats lost seats in the midterm elections of 1978, which pushed them towards deregulation and letting unions fend for themselves. [5] Reagan’s tax cuts accelerated that process, and by now the ascendancy of the rich — and the plight of the average American — should be obvious to everyone.

The outsized influence of money on our political process has also become obvious, to the point that majority opinion influences government action only when it happens to coincide with the opinion of the wealthy. To a large extent even before Citizens United, and much more boldly and obviously after, large corporations and wealthy individuals buy the laws they want.

The outsized influence of money on our political process has also become obvious, to the point that majority opinion influences government action only when it happens to coincide with the opinion of the wealthy. To a large extent even before Citizens United, and much more boldly and obviously after, large corporations and wealthy individuals buy the laws they want.

It’s not hard to make the connection between these odious results and the conservative principles that have dominated our politics since Reagan: low taxes on the rich, loose regulations on corporations and banks, and a Supreme Court that believes money is speech and corporations are people.

So the Reagan paradigm should be vulnerable.

What is success? In The Democracy Project, David Graeber measures the success of a revolution not by whether it seizes and holds power, but by whether it changes “political common sense”. By that measure, he judges the French Revolution a success: It may have ended up giving power to Napoleon rather than the People, but afterwards the divine right of kings was dead as a political principle, while “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity” lived on.

Conversely in America, changing the party in power does not always (or even usually) start a new era. The Republican presidencies of Dwight Eisenhower and Richard Nixon did not end the New Deal/Great Society era of liberalism, and the Democratic presidencies of Bill Clinton and Barack Obama did not end the conservative Reagan era. Here at the end of the Obama administration, political common sense has not changed much in decades: The basic assumptions of what government does, what problems it should and shouldn’t address, and the range of possible solutions that can be debated are more or less what they were in 1995 or 1982. To the extent those things have shifted, they’ve flowed ever further to the right.

So a real political revolution will not happen just because we elect a new president, not even one whose agenda is as transformational as Bernie Sanders’. It’s not hard to imagine conservatives repeating against President Sanders the game plan that worked against Obama: Obstruct everything he tries to do, then present him as a failure and a disappointment in the 2018 midterm elections. If Sanders’ 2016 victory has depended on impulse voters liking the sound of him (but not changing their political identities), that plan should work again. By 2018 they will have lost interest, and Republicans will sweep a low-turnout midterm.

What would a real political revolution look like? We can’t start a new progressive era in American politics by getting low-engagement voters to show up once. The revolution does have to have an electoral component, but it also needs to proceed on two other levels.

Most simply, our appeal to impulse and alienated voters needs to be more sustainable. [6] 2008’s “Hope and Change” and “Yes We Can” were inherently single-use slogans. In 2010, it was impossible to pivot from “Yes We Can” to “We Would Have If Those Bastards Hadn’t Stopped Us”. (Contrast those single-use slogans with Reagan-era memes that are still with us: small government, strong defense, family values.) Here, things are improving: Bernie Sanders’ focus on “the rigged economy” is something that progressives can keep coming back to until we get it fixed. We need more such phrases.

At an even more fundamental level, though, we need to change the ways that people identify with politics. We need more Democratic players and fans, who stay loyal from one cycle to the next, so that we aren’t depending on unreliable impulse voters to put us over the top.

This level of social engineering is beyond my competence, but it’s not impossible.

The old-school method, which I believe still works, is to build on our initial success by connecting the changes we’ve achieved to positive change in people’s lives. My own family is an example: I don’t know what political identity the Muders had in the 1920s, but a story I heard again and again growing up was how in the 1930s my grandfather managed to stall the bank from repossessing the family farm until the New Deal’s farm loan program started. That saved the farm and we’ve been Democrats for four generations now.

But that snowballing sense of progress is exactly what Republican obstruction has tried to deny us these last seven years, with considerable success. The only major advance we’ve seen recently is ObamaCare, which is why — even as we push for a single-payer system — we need to stop running it down. It’s saving lives. If the saved people realize that and tell their family and friends, we’ll have a lot more reliable votes. Maybe soon all the minimum-wage workers who get a raise will join them.

But while snowballing progress is the fastest way to change political identities, it’s not the only way. An alternative is to create and support and grow local institutions that create liberal community, as the Reagan conservatives did with fundamentalist churches. Unions would be ideal, but if that clock can’t be turned back, there are other possibilities: What if instead of relating to politics through her fundamentalist church, a housewife started getting her political identity from her co-op grocery or a local environmental group? Even something that isn’t overtly political — say, a folk music cafe — can liberalize the identities of the people who feel part of a community there.

The wild card in this process — which I hesitate to speculate on because I’m such a novice myself — is social media and the various forms on online community. What can we create that people can belong to, that will reinforce their identities as progressives?

When people decide to vote or not vote, or when they stand in the voting booth deciding which oval to darken or which lever to pull, they shouldn’t feel alone. They should feel part of a community that is interested in what they are doing and why. Which community that is will determine elections for decades to come.

When you change that, you’ve made a revolution.

What about that waitress? I never became a regular at that restaurant, and young waitresses switch jobs often anyway, so I didn’t keep track of her. For all I know, by now she might have changed and become deeply political. Who can say what might have caused it? Maybe she had children and started wondering who regulates the corporations who make the processed food she’d been feeding them. Maybe she got to know the Hispanic workers in the kitchen, and realized they can’t be what’s wrong with America. Maybe she found Jesus and became an anti-abortion crusader. When you’re talking about individuals, anything can happen.

But whether she has changed or not, America still has lots of impulse voters and citizens alienated from the political process completely. You can win a single election by convincing a bunch of them that you are sufficiently different that they should take a chunk out of a single day to come vote for you. But you can’t make a revolution that way.

To make a revolution, you need to get a large number of them to change their political identities and become players or fans of your team. You need to inspire fans of the other team to get their political identities from a different part of their lives, some part that will connect them to your team instead.

That’s a lot more complicated than just getting out the vote, and it takes a lot longer. But that’s what needs to happen, if you want a revolution.

[1] Lincoln’s success, in fact, depended on finding the right compromise position on slavery — one a bit less radical than that of Seward, the early Republican front-runner.

[2] That story is told in Jane Mayer’s recent book Dark Money.

[3] See Ian Haney Lopez’ book Dog Whistle Politics, which I summarized in “What Should Racism Mean?“.

[4] Part of the credit for the Ted Cruz victory in the Iowa Caucuses has to go to the endorsement of Duck Dynasty‘s Phil Robertson, who appeared with Cruz in an ad.

[5] That interpretation was already apparent by 1984 when Thomas Edsall wrote The New Politics of Inequality.

[6] At an even more basic level, we need to recognize the existence of low-engagement voters, and stop being ashamed of appealing to them. Idealistic liberals look askance at Madison Avenue tactics. But phrases that speak to low-engagement voters — like Sanders’ “rigged economy” — need not be empty. If we’re communicating something real to voters — something we can back up with data and policy for anyone inspired to dive into the details — rather than just trying to trick them into voting for our candidates by taking advantage of their ignorance, we have nothing to be ashamed of.

Comments

Interesting post but your waitress doesn’t fit into any of the categories you list. She appears to represent a class of people who are genuinely ignorant of our governmental structure and democratic processes. We can argue about the causes for this, but it is a serious problem that I believe, is getting worse. I would blame the major media, including “Faux News” and right-wing radio but that would assume that these people are actually exposed to those voices. As an aside, I have voted in every election that I was legally entitled to vote in, including my period of active duty military service. Many, if not most, of my votes were irrelevant to the outcome from my vote for McGovern in Massachusetts through my votes for Pete DeFazio in Oregon’s 4th District to my current votes for the opponent of Greg Walden, right wing Republican who has turned a blind eye to the sedition occurring in Eastern Oregon.

Excellent analysis. The “non-voting, dis-interested” sporadic voter clearly feels that most politicians aren’t interested in addressing their needs, so, why bother? For working people, taking time to vote can require a serious juggling of work schedule, child care, etc. Further, the fact that Republicans have made voting so tedious and difficult doesn’t help – which, of course, is no accident. In addition, many of these non or sporadic voters probably don’t read much critical commentary and focus on packaged opinion instead of objective reporting and analysis. These people have gave up on the Democratic process being a relevant force in their lives. Apathy is learned behavior, and until peoples’ situations become desperate, the political process is irrelevant. Revolutions still require organization and an over-arching theme. That a Donald Trump understands that AND is able to package his message to motivate this group – reinforces the need and the audience existence. It will be interesting to see what will motivate the outlier voter in 2016…..if they are motivated at all.

As for the young uninformed waitress – at least she was moved to ask the question. Too bad that so many people are so dis-interested and disconnected from the process that basically could make so much difference in their lives. The party that figures out how to engage in a meaningful way with them, likely will win many elections.

I think you need to start from where people are. Maybe they don’t care about politics, but they care about something. Maybe the waitress (or whoever) wants better bus service, or higher wages, or lower tuition, or something. Start with whatever they care about and connect the dots back to who makes the rules about that thing they care about.

I really like this. It’s so crucial to get across that real change can only be built over time, together, with the hard work of a lot of people. I especially like the way you talk about helping people connect to politics by building community, which is so deeply needed and in such short supply. (I think a case can be made that the whole reason for conservative ascendancy is the relentlessly growing isolation of individuals in this society — one reason this agnostic does NOT get excited when he reads about millions of people abandoning religious communities.)

I’m experimenting on an essay that casts fundamental political change as a “quest,” one that is likely to take a lifetime or longer, with many different kinds of imperfect people contributing what they can, when they can.

If you think about the way people quest in Lord of the Rings and other resonant quests of (at least) Western culture, these are ventures that bring widely different people and personalities together, each with their own motivations, strengths, and shortcomings.

Quests carry a sense of nobility and tragedy rather than anger. When a member of the Company falls short, we are saddened rather than infuriated at their impurities. When there are losses, these are understood as part of the process of doing something extremely difficult, enormous, and crucially important.

I believe we need to help people connect to something that is not ephemeral, and perhaps this is one way to transform the endless frustrations of political activity into something positive.

Among other things, we on the left need to become much better storytellers.

“We on the left need to become much better storytellers.”

Boy, is that true. Not only is the message critical (Obama used it to great advantage to “inspire” people), but Democrats are notoriously inept at marketing their achievements. This is one of the reasons why people vote against their best interests (not the only one, for sure). How much better to inspire political involvement through inspiration than through desperation.

yes – democrats or progressives need to be better story tellers. connecting the dots in a tangible way so that people understand why the republican myth of low taxes, no regulation, laissez faire capitalism is bad.

I kind of wish democrats were willing to sling mud with the zeal that their right-wing counterparts do. Even if it’s not based on fact, it goes a long way to distracting the republican attack machine. It may not be honorable, but has worked at derailing promising democrats. (That’s part of my problem with Sanders. I just don’t know how he will react to the republican attack machine if he becomes the democratic nominee. I’m hoping he surrounds himself with people who can coach him. Sincerity is nice, but being innocent doesn’t mean you won’t get wrongly convicted for a crime in our judicial system. The same is especially true for our political system.)

Bernie needs to hammer in the points of – flint michigan – with pictures of babies. Pictures of little white kids who have to drink coal polluted waters. Show pictures of people who are finally getting their medication. Show crumbling roads and overcrowded schools as a failure. Show how stupid republicans are if they can’t read the common core standards. Shout out how many americans were murdered in the wars. Shout out how many americans were murdered before Obamacare was implemented. Twist everything to make it an issue of “Republicans want to kill your babies. Are you going to let that happen?”

Fascinating analysis. Two additional thoughts. First yyour waitress was also uneducated about the structure of her own government. Since few schools teach civics any longer we have a lot of people who just don’t know. I admire her for asking the question. But how do we remedy the basic problem. If once she knows she still doesn’t vote then she is in the category you talk about. Second thought: Long ago when I was Ina college I wrote a thesis in why people don’t vote. One of the reasons is when they are pulled in multiple directions by friends and family, people often just don’t vote. In our family the kids are totally for Bernie while I the mother am for Hillary. But the amount of lobbying I’m getting for Bernie has made me stop and reconsider. If I were less political I just might not vote as a way to avoid an argument. Same for republicans split in so many directions. We should watch that.

Good points, ChristineB. Here’s another thought: explain to your kids why you think a vote for Hillary is best for the party you both support. Not voting is never a solution, even if it happens. If you are an informed voter, which I expect you are, you should be able to convey what your reasons are for supporting your candidate. While that may not sway your children, at the very least, it should make them think.

The MOST important discussion you should have with them is “what will they do if Bernie doesn’t get the nomination”? It is critical that they go out and vote for Hillary – that is where your informed, convincing information about her candidacy will be important. The Democratic Party can not lose Bernie’s supporters if he doesn’t win the nomination. This race will ultimately determine the make up of SCOTUS which is becoming more and more a political, legislating body than one would have every thought could happen. Then, there’s health care reform, and the very real problem your kids may be interested in – student loan debt. That debt is the next big financial crisis in America and it is coming. I can assure you that Democrats are far more likely to resolve it in a way that will be less painful to students (and their undersigned parents/guardians) than will Republicans. The last point is equal rights – for women, gays, choice, justice….2016 is a major political year which will likely determine the course of history – both political and social for decades ahead.

Glad you were able to come to a decision you feel is the right one! I think the idea that voting for Sanders is a way to encourage more liberal candidates to run has some merit, and in that way, I can understand where you’re coming from. A strong showing for Sanders (whether he gets the nomination or stays competitive into June) could have that snowball effect you’re talking about – the more people see the liberal candidate as viable, the more likely they are to vote for him/her, and the more likely liberal candidates are to get into the “race.” It sounds nice and seems to have some logic, but I also wonder if there’s not an element of wishful thinking (on both our parts.) Parties and donors tend to support incumbents rather than newcomers, so perhaps the “snowball” will be that politicians already in office feel comfortable moving left or feel like they have no other choice. I suspect without Sanders in the race, Clinton would be running more of a general election campaign at this point by appealing to the (somewhat mythical) middle. Which does not, in my mind, mean she’s insincere about her progressive ideas or plans, just that she would be able to focus on criticizing the Republicans and pitching her ability to unite different groups of people. As it is, she’s having to defend and demonstrate her progressive/liberal bona fides. To keep the snowball moving though, we’d have to persist in supporting candidates for multiple election cycles.

I do find it interesting that you get to make this choice and it seems as though you might have made another if Clinton’s candidacy was at risk in the general election or you voted later in the primary. The two states to vote first in the primary season are very, very white. I wonder if the element of “dream big and bold” is something that white voters get to embrace because we rely on minorities to be pragmatic for us later on. “I will send a message to the establishment to let them know they need to change” vs. “The Republicans don’t even think I’m a human who’s worthy of protection and respect, and I can’t risk giving them any more control over my life.” I have friends who have vowed to vote for Jill Stein if Sanders doesn’t get the nomination because they say they can’t trust Clinton, can’t reward the establishment, etc. And I can’t help but look at them and think, “What a privileged world you live in where politics gets to be about your perfect ideals when the rest of us have to worry about whether we’re going to be treated like human beings.” Some of them have come back with “We’ll never change anything if we keep giving in,” and I can understand that but I still can’t help but think it’s African Americans and Hispanics and LGBT folks and women who bear the burden of inequality in the meantime.

None of that is meant to be a criticism of you or anyone else for that matter – it is more an observation about how political choices and identities are not necessarily tied to single or even a few issues. People vote against their economic interests because cultural issues matter to them more. People will vote against a candidate who mostly agrees with them about the priorities of governance because pragmatism feels like surrender. In that sense, I think you’re spot on about the need for community building on the left, but the “revolution” rhetoric is beginning to really bother me.

The Sanders campaign has not put out any substantive analysis with polling numbers, profile data, or an action plan for getting these non-voters into the voting booth for multiple cycles to facilitate the revolution. (Non-voters may trend Democratic, but not all of them will be and not all of them are non-voters because they’re disgusted with money in politics or the establishment. Some of them really just don’t care, no matter what the message is. Do we know what the breakdown is? Do we have a guess for it? What are the steps to change their political decision-making as you noted?) That is not to say that Sanders doesn’t have a plan for this, but I haven’t seen anything that doesn’t warrant the slightly mocking phrase of “1) Millions of people 2)??? 3) Revolution!”

Not to mention, the American system of government is not designed to facilitate rapid change – even if you could wave a magic wand and limit money in politics (to some undetermined, agreed upon level that facilitates campaigns but doesn’t influence votes?), the system still would not allow rapid, revolutionary change. Checks and balances, separation of powers, the legislative process, the amendment process…hell, the federal system itself splits power between states and the national government…that does not allow for rapid change. The branch most likely to effect rapid change is the judiciary and then you have to have the right case in front of the right judge with the right ruling that will be enforced by willing executives. It took 60 years to overturn Plessy vs. Ferguson, and even then. enforcing Brown after 1954 did not go smoothly. At all.

I agree with a lot of Sanders bold ideas, and I genuinely like him. He seems like a good man who really wants to help people. But his current plan of “political revolution” makes me very, very nervous. Not because I think it’s impossible or not worth pursuing but because relying on people who are historically disengaged from the politics seems like awfully shaky ground. And then you run into institutional problems of how governing works in the US, not just the money but the system itself as laid out by the constitution.

As an aside, I’d love to see what you think about who the “political revolution” would help in the event it happened (in whatever ways might be possible). Millions of people rising up to get money out of politics and putting an end to the historic levels of economic inequality. Because I’ve been thinking about that myself and when I consider who’s going to benefit the most from better, fairer economics, and I’m not so sure the revolution would be all that revolutionary for women, minorities, or LGBT folks. Money gives people more options in protecting themselves and their interests, but it doesn’t stop other forms of inequality and oppression.

Great articles as always!

For a guy who writes with some facility about politics, you seem to have covered your head with your hoodie in overlooking her financial connections. rcwortman250@comcast.net

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/charles-ferguson/hillary-clinton-bernie-sa_b_9172128.html?utm_hp_ref=politics

THE BLOG Hillary Clinton, Bernie Sanders, Wall Street, and America 2.0 02/05/2016 06:21 pm ET | Updated 1 day ago

* Charles Ferguson

JUSTIN SULLIVAN VIA GETTY IMAGES

The stunning ascent of Bernie Sanders portends far more than a hard-fought Democratic primary. Its greater implication, whether Sanders wins or loses, is that America’s crony capitalism will no longer go unchallenged. Thus Hillary Clinton and her husband, along with many others, are increasingly trapped by the wealth, credentials, and insider status they have pursued so fervently – because they derive from a corruption whose nature and consequences can no longer be concealed. America’s financial elites are now so corrupt, arrogant, and predatory that political leaders beholden to them can’t even pretend to deliver economic or political security, much less fairness or progress.

And now, finally, Americans are running out of patience. In addition to Bernie Sanders, there’s Elizabeth Warren, Zephyr Teachout, and even movies – The Big Short has (deservedly) grossed $100 million. Everything suggests that American politics is now truly, fundamentally, up for grabs – a hugely exciting but also terrifying prospect. In America, the Great Depression yielded Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal; but in Europe, it created Hitler and Mussolini. America’s reaction against its corruption and decline could show us at our best – or our worst.

Indeed, this is the Democratic establishment’s rejoinder to Bernie Sanders: he’s a wonderful dreamer, but impractical – he can’t get elected, so we’d get Trump or Cruz, and furthermore even if Bernie was elected, he couldn’t get anything done. Look at Dodd-Frank and Obamacare, they say – those laws barely passed. No way could Bernie break up the banks. Only a pragmatic, moderate insider can get anywhere.

Actually the truth is exactly the opposite. American insider politics is now so corrupt that nobody within it can get anything done. But by stepping outside of the rules, you could do a great deal. Let’s take a concrete example – the banks.

Start with Hillary Clinton. The sound bite is that Goldman Sachs paid her $675K for three speeches. The full reality is far worse. She, her husband, and their advisers have history with the banks going back decades. Bill Clinton made Robert Rubin, former president of Goldman Sachs, his Treasury secretary, then appointed Larry Summers and Laura Tyson to succeed him, and re-appointed Alan Greenspan as chairman of the Fed. Together, they let the banks run amok; in fact, they helped them. They repealed Glass-Steagall, banned the regulation of derivatives, refused to use the Fed’s authority to regulate the mortgage industry, and did nothing as massive securities fraud permeated the Internet bubble. Then Rubin became vice-chairman of Citigroup, while Tyson joined the board of Morgan Stanley. Bill Clinton, Rubin, Summers, Tyson, and Greenspan all share major responsibility for the 2008 global financial crisis, and none of them have been remotely honest about it.

Since leaving office, both Bill and Hillary have made millions of dollars giving speeches to banks while being remarkably quiet about prosecution of financial crime, not to mention the Obama administration’s appalling record since the crisis – zero prosecutions, bankers in senior regulatory positions, inviting bank CEOs to state dinners dozens of times, et cetera. Now Hillary says she’ll rely on Bill for economic policy. Bad idea. The financial sector became a pervasively criminal and economically destabilizing industry largely through Clinton policies, and now Hillary takes their money. When pressed, Democratic insiders concede all this, but then say, well, OK, the financial sector is just too powerful to rein in, but think of what Hillary could do in, say, education.

Let us therefore take a brief tour of the Education Management Corporation (EDMC), one of the most repulsively predatory companies in America. EDMC specialized in exploiting poor people seeking to better themselves educationally. It used fraudulent marketing, luring students into paying high tuition – by taking out student loans signed over to EDMC. EDMC kept all the money, but provided abysmal schooling with high dropout rates. EDMC made huge profits while poor students wasted time, obtained no skills, and dropped out with crushing debts.

EDMC raked in $11 billion this way. Assuming, say, $11,000 per student, EDMC screwed one million poor Americans. Eventually the Justice Department sued, but as usual the settlement was a wrist-slap with no criminal prosecutions, no admission of guilt, and no financial relief to victims.

But why am I telling you all this?

Well, now. Who devised EDMC’s strategy, aided by relaxed Federal regulation? Who was EDMC’s largest shareholder, buying 41% of the company in 2006?

Goldman Sachs.

Now, Hillary, when you and Bill have your little cocktail parties for the Clinton Foundation in Goldman Sachs offices, when you give your speeches to Goldman Sachs executives, when you chat them up for donations, when you meet them at White House state dinners, just how frequently do you bring this up?

OK, Hillary ain’t so great. But could Bernie do any better? Well, he could appoint an Attorney General and a head of the DOJ Criminal Division who haven’t spent their careers defending corporate criminals, and then invite the Justice Department to put lots of bankers in jail. (There is overwhelming evidence to justify doing so; for details, read this, or chapter 6 of this .) Bernie could also appoint an Antitrust Division head who would actually investigate the cozy, cartel-like arrangements that pervade finance, and bring major cases against the banks. He could appoint a Federal Reserve chair who would require banks to divest assets and operate safely, plus regulating bankers’ compensation so that if you caused a disaster, you couldn’t profit from it. All this can be done without a single new law, and both Bill Clinton and Obama could have done them too.

Now, can Bernie Sanders get elected? And are we willing to take the risk that if he loses, we’d get an insane Neanderthal like Trump or Cruz running the country? Honestly, I’m not sure. For one thing, Bernie had better stop calling himself a socialist. But I’m damned sure that if he was elected, he’d do a lot more than Hillary Clinton would. And I think that the American people have figured this out.

One issue with appointing the AG or Fed chairman – the Senate has to approve them. Considering the GOP delayed Loretta Lynch’s nomination for something like 3 months (despite no substantive issues with her or her performance record), I can’t imagine what sort of hair-on-fire magic they’d invoke to delay the nomination of someone who had vowed to pursue the very things you’re arguing they should pursue. That is not an argument to accept cozy relations between politicians and the financial masters of the universe, nor is it a dismissal of the Clintons’ relationships with wealthy bankers. Merely a note to remind us that President Sanders would be stymied at nearly every turn unless he gets Democratic majorities in both houses. Not just any old majority – super majorities. I think Sanders would be wiling to settle for incremental progress when necessary were he to get into the White House because he’s been a politician for 40 years. I don’t know if his base of supporters would and then we run the risk of another 2010 – progressive voters losing interest or abandoning their president (and down ballot candidates) because he turned out to be pragmatic and/or ineffective.

Also, he’s already called himself a democratic socialist enough for the GOP smear machine to grab it and twist it into a diatribe about how he hates America, apple pie, and puppies. Younger voters might not care about the label, but the most reliable bloc of voters is over 45, and they’re the ones that vote in mid-terms – they very well might care because they are old enough to remember the Cold War.

Things that are “obvious,” yet not born out in the results we see around us, often turn out to have been wrong all along. You allude to the obvious connection between Reagan era tax cuts and declining middle class prosperity, but when you look at census data on relative incomes it becomes clear that the declining share of income earned by middle cohorts has been declining since the late 50’s.

Sometimes those obvious assumptions can surprise us in ugly ways. I’d wager that your waitress, if she were ever to become politically active, might turn out to be a Trump voter. Many Democratic assumptions about the potential of those latent voters to foster a ‘revolution’ may be horribly, horribly misplaced.

Take a look at the slate of delegates Trump assembled in Illinois for an example: https://goplifer.com/2016/01/06/a-survey-of-trumps-illinois-delegates/

Impulse voters and the alienated voters would seem to fit into the categories of “uninformed” voters and Fox news “misinformed” voters who are even less receptive to rational persuasion than “uninformed” voters.

My hunch is that Bernie’s message is more likely to resonate with these non-voters or voters who only vote in presidential election years.

Even getting their attention requires a simple message that appeals to either their self interest or identity to motivate them to actually vote. That’s part of the reason I see Bernie as more electable than Hillary.

Spelling: precede -> proceed

Oh, dear Doug. Much as I love you (and I *do* love you) sometimes you nail things on a macro level and miss the micro. And vice versa. This post is a case of the former.

A young female server is necessarily “working class”? Oh hell no. My own experience suggests that she might well have been an art history major earning pocket money. Perhaps she was not only the owner of that eatery but of a chain of similar restaurants as well (OK, so maybe not likely). Maybe she was working her husband’s way through med school) (these days, again not so likely). Maybe she was the daughter of the plutocratic owner of a chain who insisted on her learning the ropes from the ground up. These days, one can NOT assume a person’s socioeconomic status from whatever work from whatever work they’re doing at the time.

(Had you stated outright that your server had an accent I would have accepted much more readily your assertion that your server was necessarily working class, but I’m in California, and by necessity cynical.)

My point is that socioeconomic boundaries are more fluid than most people seem to realize they are, but trend strongly downward. And for women that’s doubly true.

(And THANK YOU for declaring for Bernie.)

I was leaning Bernie and now in the other direction. The issue you hint at but seems to be really missing in current political discussions is the over-focus by Progressives and even Democrats as a whole on the Presidency. Your waitress may be an example. One of the ways a small party like the Republicans can wield so much power is that they focused their energy not on an “all or nothing” revolution at the top but began organizing at the local level to take over school boards, city councils, state legislatures, etc. The midterms go badly for progressives not merely because of turnout but because of gerrymandering. Generally more people vote for Dems in midterms but the Repubs have concentrated those voters in consolidated districts so they have less power. They focused on the Supreme Court and changing it as early as the 50’s. To talk revolution to the young people without really talking how to organize or thinking strategically make me begin to see Sanders as more of a niche candidate as much as I agree with him on the issues. I also am a woman and few progressives have Hillary’s record with the issues that particularly affect women. And since so many poor families are headed by women these issues are particularly cogent for those with a progressive heart.

Exactly. When we look in the mirror, even Pres. Obama looks good in comparison to the line-up on the right. Liberals need to be smart about this election. There is so much riding on keeping the Presidency as a checks and balance on an ultra-conservative Congress. Vote with your head, not your heart.

(http://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/09/opinion/i-miss-barack-obama.html?_r=0)

“Do I wish Obama had pushed harder on progressive issues (the way he started doing after 2014, when he had no more elections to face)? Yes, I do. But do I think he could have turned the 2008 coalition into a permanent electoral force that would have transformed American politics the way FDR did? No. I think that reading of recent political history is unrealistic, because the transformation Obama was supposed to catalyze depended on alienated and impulse voters suddenly deciding to change their personal identities and see themselves progressive activists and apostles.”

We’re essentially talking about a two-year span. Obama had to hold it together for two goddam years, just long enough to goose a somewhat larger midterm turnout than usual. That’s it. We’re not talking about the spontaneous formation of workers’ collectives throughout the land. 2010 determined how redistricting would go, and with it, the next decade. So it was kinda sorta important to pay a bit more attention to that midterm than most. Ummmm….. You knew that, right? I assume Obama knew — him being the great “constitutional scholar” ‘n’ all — so I guess he just didn’t really give a fuck.

In 2009, as soon as he came into office, Obama had the kind of foil every (competent) politician dreams of: The finance industry, Wall Street — which had just trashed the economy. Do you think the phrase “malefactors of great wealth” might have pulled out of the vault and used to some effect? Aggressive action to spur the economy AND bring some oligarchs to justice could have got a real coalition going for at least two years. That coalition in turn could have made genuine health care reform a reality, instead of the Rube Goldberg apparatus we’ve got. In politics you go from strength to strength.

But we know what we got instead. Rube Goldberg, and a two-year circle jerk in which Obama insisted on “bipartisan” collegiality from Republicans who from the start explicitly vowed to oppose his every move. And let’s not forget the occasional jab at left-wingers — from Obama and his hangers-on!

But yeah, plainly it was those “impulsive” voters who fucked up. After all, what can a mere president do? How can he ever hope to get anybody’s attention?

Reblogged this on Life Weavings and commented:

“At an even more fundamental level, though, we need to change the ways that people identify with politics. We need more Democratic players and fans, who stay loyal from one cycle to the next, so that we aren’t depending on unreliable impulse voters to put us over the top.”

See also: http://lifeweavings.org/2015/05/01/a-democracy-of-kingship/

Trackbacks

[…] This week’s featured post is “Say — you want a revolution?“ […]

[…] A more subtle problem for Sanders was pointed out Saturday by Rachel Maddow, and then fleshed out on MaddowBlog by Steve Benen: When you ask Sanders’ supporters how he will get elected in the fall and how he will get Congress to pass his programs after he takes office, they talk about a “political revolution”. In other words, Sanders will energize previously apathetic or discouraged voters, creating a tidal wave of support from people whose opinions had not affected American politics until his campaign gave them a voice. (I critiqued that vision two weeks ago.) […]

[…] seeing here is the low-engagement voter problem that I discussed a few weeks ago in “Say — you want a revolution?” Large numbers of voters have not thought through the issues well enough to have a coherent […]

[…] consider this note a follow-up on the voter model I presented in “Say, you want a revolution?“. If you’re politically active, you need to understand that the voters may not be who […]

[…] In general, I never saw the Bernie/Hillary argument as being about goals. Rather, it seemed to me to revolve around methods and tactics: Is it better to push for big, revolutionary changes or to head in the same direction in incremental steps? And I was skeptical that electing a progressive president could actually bring about that revolution without a more fundamental re-education of the electorate, as I spelled out in “Say — You Want a Revolution?” […]

[…] still believe the model I put forward last February in “Say – you want a revolution?“: The vast majority of non-voters are people who don’t have a political identity at […]