Technically, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the baker. But it didn’t endorse any of the larger points he raised. What, if anything, does this mean for future cases?

The Masterpiece Cakeshop case is the legal equivalent of the movie Solo: Touted as a blockbuster in the series of landmark cases that includes Obergfell and Hobby Lobby, it turned out to be a dud.

You’ve probably already heard the basics of the case: In 2012, before same-sex marriage was legal in their state, Charlie Craig and David Mullins were planning to get married in Massachusetts, and then have a wedding reception back home in Colorado. They went to Masterpiece Cakeshop to order a custom-designed wedding cake, but the owner, Jack Phillips, refused to discuss it with them. Attributing his position to his Christian faith, he said he couldn’t be involved in celebrating a same-sex marriage. Craig and Mullins sued under Colorado’s anti-discrimination law, and they won at every level. So Phillips appealed to the Supreme Court.

What everybody expected. The case was supposed to be a 5-4 decision, as all nearly all the same-sex marriage decisions have been. Four conservatives (Thomas, Alito, Roberts, and Gorsuch) would line up with Phillips and four liberals (Ginsburg, Sotomayor, Breyer, and Kagan) with Craig and Mullins, with Justice Kennedy casting the deciding vote, as he usually does.

Nobody was too sure what he would do. He has authored (badly, in my opinion) most of the landmark gay-rights decisions of recent years, but (as part of the 5-4 majority in Hobby Lobby) he also was also known to be sympathetic to the kinds of religious-liberty arguments Phillips was making.

However this case came out, though, we were all sure it would have sweeping consequences: Either the Court would affirm that gays and lesbians have to be treated like everyone else, or it would establish “sincere religious belief” as a permanent loophole in our discrimination laws. [1] That’s not what happened.

That’s not what happened.

Instead, the Court decided 7-2 that the Colorado Civil Rights Commission hadn’t handled this particular case with proper respect for Phillips’ religious views, and so the Court threw out the decision against him. Essentially, we’re back to Square One: It’s as if Craig and Mullins had never filed their complaint.

Here’s how limited the decision is: If tomorrow another same-sex couple goes to Masterpiece Cakeshop asking for a wedding cake and Phillips turns them down, nobody knows what will happen next.

This is how that 7-2 breaks down:

Thomas. Justice Thomas went whole-heartedly for the baker’s argument: Phillips is an artist, and the government cannot command him to create a message he finds abhorrent. Quoting previous free-speech cases, he says:

Forcing Phillips to make custom wedding cakes for same-sex marriages requires him to, at the very least, acknowledge that same- sex weddings are “weddings” and suggest that they should be celebrated—the precise message he believes his faith forbids. The First Amendment prohibits Colorado from requiring Phillips to “bear witness to [these] fact[s],” or to “affir[m] . . . a belief with which [he] disagrees.”

Gorsuch and Alito. Justices Gorsuch and Alito (with Gorsuch writing for both of them) believe that the Colorado Civil Rights Commission has itself discriminated against Phillips because of its hostility to his religious views. They see Phillips’ case as being equivalent to that of William Jack, who intentionally tried to create such a comparison.

[Jack] approached three bakers and asked them to prepare cakes with messages disapproving same-sex marriage on religious grounds. All three bakers refused Mr. Jack’s request, stating that they found his request offensive to their secular convictions. But the Division declined to find a violation, reasoning that the bakers didn’t deny Mr. Jack service because of his religious faith but because the cakes he sought were offensive to their own moral convictions.

… The facts show that the two cases share all legally salient features. In both cases, the effect on the customer was the same: bakers refused service to persons who bore a statutorily protected trait (religious faith or sexual orientation). But in both cases the bakers refused service intending only to honor a personal conviction. To be sure, the bakers knew their conduct promised the effect of leaving a customer in a protected class unserved. But there’s no indication the bakers actually intended to refuse service because of a customer’s protected characteristic. We know this because all of the bakers explained without contradiction that they would not sell the requested cakes to anyone, while they would sell other cakes to members of the protected class (as well as to anyone else).

… Only one way forward now remains. Having failed to afford Mr. Phillips’s religious objections neutral consideration and without any compelling reason for its failure, the Commission must afford him the same result it afforded the bakers in Mr. Jack’s case.

So that’s three votes for the baker’s case on the merits. Two more votes and Phillips would get the kind of result he (and the Alliance for Defending Freedom, the Christian-religious-liberty organization arguing his case) had been hoping for: At least in Colorado, bakeries (and presumably florists and caterers and all kinds of other businesses) would be free to deny their services to same-sex couples.

Kagan and Breyer. But you may have noticed a problem in the Gorsuch-Alito reasoning. How could they say Phillips “would not sell the requested cakes to anyone”, when he happily makes wedding cakes for opposite-sex couples? That’s because in their reasoning, a gay wedding cake is a thing. Phillips also wouldn’t sell a “cake celebrating same-sex marriage” to Craig’s mother, who is straight, so he’s not just refusing to sell to gays.

Justices Kagan and Breyer (Kagan writing) found this ridiculous. There is no such thing as a gay wedding cake. The product is just a wedding cake, and the fact that the cake will find its way to either a same-sex or opposite-sex wedding reception does not make it a different product.

And that’s the difference between the Phillips case and the Jack case: The anti-gay message in the Jack case was on the cake. (One cake would have said “God hates sin. Psalm 45:7” on one side and “Homosexuality is a detestable sin. Leviticus 18:2” on the other. Another Jack cake would have put a red X over an image of two groomsmen holding hands.) In the Phillips case the only problem was in the use of the cake and who was using it. Phillips might legally have refused to put overt pro-gay symbols or messages on the cake (say, a rainbow flag). But refusing to make any wedding cake, even one identical to one he would make for an opposite-sex couple, was discrimination.

However, Kagan and Breyer found that the Civil Rights Commission didn’t make that argument properly, and instead some of the commissioners made statements hostile to Phillips religion. This created the impression that the commissioners were responding to their personal beliefs rather than legal principles: They found Jack’s message offensive, but not the Craig-Mullin wedding cake. In short: The CRC could have justified the findings it made, but it didn’t, so its decision in this particular case should be thrown out.

Ginsburg and Sotomayor. Justices Ginsburg and Sotomayor (Ginsburg writing) spelled out in more detail the difference between the Jack and Phillips cases:

Phillips declined to make a cake he found offensive where the offensiveness of the product was determined solely by the identity of the customer requesting it. The three other bakeries declined to make cakes where their objection to the product was due to the demeaning message the requested product would literally display.

Ginsburg and Sotomayor scoff at Gorsuch’s notion that the product was a “cake celebrating same-sex marriage”.

When a couple contacts a bakery for a wedding cake, the product they are seeking is a cake celebrating their wedding—not a cake celebrating heterosexual weddings or same-sex weddings—and that is the service Craig and Mullins were denied.

The merits of the case matter more than any procedural errors the Commission may have made.

I see no reason why the comments of one or two Commissioners should be taken to overcome Phillips’ refusal to sell a wedding cake to Craig and Mullins. The proceedings involved several layers of independent decisionmaking, of which the Commission was but one.

The Colorado Court of Appeals, Ginsburg notes, “considered the case de novo“. (In other words: It started over, and considered the case on its merits rather than on the basis of what the Commission had done.)

What prejudice infected the determinations of the adjudicators in the case before and after the Commission? The Court does not say.

In a footnote, Ginsburg-Sotomayor also tear up Thomas’ free-speech argument: A message may be in Phillips’ mind, but it isn’t in the cake unless other people can see it there.

The record in this case is replete with Jack Phillips’ own views on the messages he believes his cakes convey. But Phillips submitted no evidence showing that an objective observer understands a wedding cake to convey a message, much less that the observer understands the message to be the baker’s, rather than the marrying couple’s.

It comes down to Kennedy and Roberts. So three justices agree with the baker on the merits and four don’t. But two of the four also find procedural problems in the rulings against the baker. So it’s already clear that the baker will win the case: The judgment against him will be thrown out. The question for the remaining two justices — Kennedy and Roberts — to decide is whether the Court will create a precedent that similar cases can appeal to.

Roberts’ thinking is usually subtle and often hidden. He will, at times, rule in a way that technically upholds a precedent, while re-interpreting it in a way that will ultimately undo it in subsequent cases. (In a current case that I’ll discuss in the weekly summary, his decision upholding the constitutionality of the Affordable Care Act in 2012 is now the basis for a new case claiming it is unconstitutional. He does that kind of thing.)

Roberts is happiest when he is changing society in a conservative, pro-wealth, or pro-business direction, but doing it behind the scenes. He doesn’t want the Court to make the kind of waves that could result in a major political backlash. (So, for example, he will write a decision that celebrates the principles behind the Voting Rights Act, while gutting the provisions that enforce it.)

This case is not Roberts’ style. He doesn’t want to author a sweeping takedown of anti-discrimination laws, and Kennedy isn’t going to go for that anyway. Also, he knows that the wind is blowing against him here. More and more, society accepts gay rights. The kind of sweeping decision Thomas, Gorsuch, and Alito want won’t look good in five or ten years.

So on this case he will keep his powder dry, uphold his (mostly false) image as a moderate, and go with what Kennedy wants.

Kennedy wants this case to go away. The decisions leading up to the full legalization of same-sex marriage (in Obergfell) are his legacy. When he eventually dies, that’s what his obituary will be about. He doesn’t want that record tarnished, least of all by his own decision.

But Kennedy is an empathy-based judge rather than a principles-based judge. [2] In this case, he seems to empathize with both sides: Craig and Mullin just wanted to have the same kind of wedding reception anybody else might have. Phillips didn’t want to be forced to act against what he saw as his religious convictions.

So the deciding Kennedy-Roberts opinion lets the baker off the hook on the narrowest possible grounds, without giving future courts anything to work with in similar cases.

When the Colorado Civil Rights Commission considered this case, it did not do so with the religious neutrality that the Constitution requires. Given all these considerations, it is proper to hold that whatever the outcome of some future controversy involving facts similar to these, the Commission’s actions here violated the Free Exercise Clause; and its order must be set aside.

So the baker wins. But Kennedy leaves the larger issues open.

Our society has come to the recognition that gay persons and gay couples cannot be treated as social outcasts or as inferior in dignity and worth. For that reason the laws and the Constitution can, and in some instances must, protect them in the exercise of their civil rights. The exercise of their freedom on terms equal to others must be given great weight and respect by the courts. At the same time, the religious and philosophical objections to gay marriage are protected views and in some instances protected forms of expression. [3]

I find myself sharing the concern Sarah Posner expressed in The Nation: “how assiduously Justice Kennedy labored to find government ‘hostility’ to Phillips’s religion”. If a judge searches the record hard enough, with hyper-sensitivity to a hostility that he has pre-decided must be there, won’t he always be able to find some evidence of anti-religious bias somewhere?

What will be the evidence of such supposed animus in the next case? A question from a judge at oral arguments? Deposition questions by government attorneys? That is the crucial open question from Masterpiece—not whether the next case will be more winnable for a gay couple without Masterpiece’s specific facts, but how hard opponents of LGBTQ rights will work to convince the courts that similar specific facts exist in that case, too.

What next? Neither side can take comfort in the numbers. Seven justices looks like a solid majority for the conservative side, but four of the seven are only citing procedural reasons for objecting to the Commission’s ruling, and not saying they should have ruled in the baker’s favor.

Similarly, six justices reaffirm that anti-discrimination laws can apply to gay couples, whose “dignity and worth” is not inferior to opposite-sex couples. But Roberts cannot be trusted. If he could have formed a conservative majority on the other side, he quite likely would have.

So here’s where I think we are: Roberts is stalling, with the hope of getting another conservative appointment out of Trump before the Court has to make a definitive ruling. If he gets that extra conservative justice, then the Court will rule decisively to gut anti-discrimination protections for gays and lesbians, using “sincere religious belief” as the loophole.

In the meantime, look for a series of cases like this one, decided on the narrowest possible terms, and usually in favor of the conservative side.

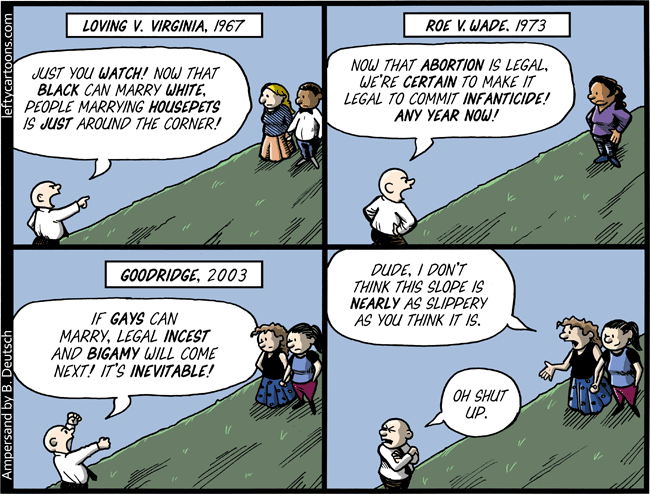

[1] Phillips’ defenders argue that discrimination against gays is special in some way, but it’s hard to see how. When inter-racial marriage was controversial, the arguments against it were also framed in religious terms. Slavery, segregation, discrimination against women — pretty much every kind of bigotry roots itself in religion when other supports start to fail. If “sincere religious belief” allows discrimination against Craig and Mullins, it’s hard to see how any discrimination law stands up.

BTW: Notice what I didn’t say there. I didn’t say that Christianity or any other religion is inherently bigoted. I’m saying that bigots will cloak themselves in religion, and will cherry-pick sacred texts to justify their bigotry. If courts let them get away with this dodge, anti-discrimination laws will be toothless.

[2] That is what has driven me nuts in his previous rulings. He consistently fails to enunciate principles that lower-court judges can apply, instead making what are essentially political arguments that one side or the other deserves to prevail. That is why same-sex marriage cases kept going to the Supreme Court. Kennedy’s opinions were murky, and lower-court judges disagreed about what they meant. Eventually each new case had to come back to Kennedy so that he could interpret himself.

[3] This kind of writing also drives social conservatives nuts. “Our society has come to the recognition …” What kind of legal principle is that?

Kennedy consistently acts the part of the stereotypic liberal-activist-judge who projects his own moral convictions onto the law. Ginsburg is much more liberal than Kennedy, but you’ll never find that kind of mushiness in her opinions. She defines terms, cites precedents, and enunciates principles that lower-court judges can apply with confidence.

Thursday, the story of the Kentucky county clerk who refused to issue marriage licenses (now that same-sex couples can marry) reached its inevitable conclusion. Having been

Thursday, the story of the Kentucky county clerk who refused to issue marriage licenses (now that same-sex couples can marry) reached its inevitable conclusion. Having been

What lies in the background of that argument is that the separation between gays/lesbians and the benefits of marriage is not something the affected individuals can easily fix on their own. Sexual orientation may or may not be innate, but it is

What lies in the background of that argument is that the separation between gays/lesbians and the benefits of marriage is not something the affected individuals can easily fix on their own. Sexual orientation may or may not be innate, but it is