Democrats and Republicans are telling us who they are.

In political novels, authors make diverse issues converge so that competing politicians, parties, or movements can demonstrate their contrasting natures within the short time-window of a plot. That almost never happens in real life — except for these last two weeks.

Recent news has featured two very different stories: Democrats passed the Inflation Reduction Act over unanimous Republican opposition, breaking the legislative logjam that (until now) has blocked Congress from from fighting climate change, cracking down on corporations that pay no tax, or lowering prescription drug costs.

Meanwhile, Republicans did their best to raise public outrage against the FBI and DoJ after they searched for — and found — classified documents that Donald Trump was holding illegally at Mar-a-Lago. As Trump’s excuses shifted from day to day, prominent Republicans dutifully parroted each one. No member of the GOP leadership even hinted that Trump should account for his actions.

In an additional subplot, chief Trump critic Liz Cheney — former member of the House Republican leadership and daughter of a Republican vice president — was overwhelmingly rejected by the Republican voters of Wyoming. The GOP is the Trump personality cult now; anyone who won’t bow down to him belongs somewhere else.

Democrats

The Inflation Reduction Act. President Biden signed the IRA on Tuesday. The bill does several things that have been popular with voters for years, but haven’t been able to get through Congress: It lowers prescription drug costs by letting Medicare negotiate with drug companies, caps how much Medicare recipients have to pay for drugs, and cracks down on profitable corporations that pay little-to-no income tax. It extends subsidies that help people afford ObamaCare policies, and also lowers the deficit by raising more revenue than it spends.

The biggest spending items in the bill are aimed at mitigating climate change, a growing problem that has been apparent for decades, but which Congress has also been unable to muster the will to address. By 2032, the IRA is expected to lower carbon emissions 40% from what they were in 2005. It accomplishes that mainly by subsidizing both sustainable electric power and the purchase of electric vehicles.

Democrats were also united around a provision to cap the cost of insulin, a life-saving drug that is out of patent and cheap to manufacture, but can cost a lot in the US (but not in other countries) due to market failures and corporate greed. Unfortunately, arcane Senate rules wouldn’t let an across-the-board insulin cap be part of a bill that circumvented the filibuster. So the Senate couldn’t pass the cap without ten Republican votes, and only seven Republicans were willing to sign on. 43 Republican senators voted to keep the price of insulin high.

Other legislative accomplishments. The IRA was the final exclamation point on a series of bills Democrats got through Congress this summer.

- A bipartisan gun control bill. It doesn’t do nearly as much as Biden wanted, but it does extend red-flag provisions for keeping guns out of the hands of high-risk people, closes the boyfriend loophole, cracks down on interstate gun trafficking, and makes it harder for 18-21-year-olds to buy guns. It’s the first major restriction on guns in decades.

- A veterans health bill in which the government finally took responsibility for the effects of toxic fumes from the burn pits used to dispose of military waste in Afghanistan and Iraq.

- The CHIPS Act, which is intended to bring high-tech manufacturing back to the US and put US tech industries into a better position to compete with China.

These bills build on a record of accomplishment from earlier in Biden’s term, like the American Rescue Plan Act (which deserves a lot of credit for the economy’s fast recovery from the Covid shutdown. Unemployment had skyrocketed during he last year of the Trump administration, but is near record lows now.) and the bipartisan infrastructure bill (which Trump had kept promising but never delivered).

More could have been accomplished if not for the two Democratic senators who refused to scrap the filibuster. If Democrats hold the House and pick up two senate seats in the fall — still a longshot, but a growing possibility — they could protect voting rights and codify the protection American women lost when the Supreme Court trashed Roe v Wade.

That’s who the Democrats are: They are concerned with real problems (climate change, unemployment, national competitiveness, the cost of health care …) and are not just posturing about them, but taking action.

Republicans

Meanwhile, the Republicans have been displaying a different nature: a personality cult whose highest priority is to defend their leader against legal accountability for his actions.

The Mar-a-Lago search. On August 8, FBI agents executed a search warrant on Trump’s Mar-a-Lago residence, which is part of his country club. They were looking for records from his administration, which according to law, belong to the government, not to him. The National Archives and Record Administration, the agency that oversees such records, has been trying to reclaim their documents from him ever since he left office.

In January, NARA retrieved 15 boxes of documents and other materials from Mar-a-Lago, but (believing they had not gotten everything) asked the help of the Department of Justice. In May, DoJ issued a subpoena which they served to Trump’s lawyers on June 3. More documents were turned over at that time, and a Trump lawyer falsely signed a document stating that all classified material had been returned.

We do not at this point know why DoJ believed classified documents were still at Mar-a-Lago, but a judge found probable cause that evidence of several crimes, including breaking the Espionage Act, was still at Mar-a-Lago. Hence the search warrant.

The FBI found what the search warrant was seeking: more boxes of documents, some of them classified at the highest levels.

So far, no one has presented the slightest evidence that NARA, DoJ, the judge, or the FBI did anything wrong. Trump has railed against all of them, inspiring one deranged follower to attack an FBI office in Cincinnati, an action that led to the man’s death. But though he has posted lengthy diatribes on his Truth Social clone of Twitter, Trump has had nothing to say about the most important questions:

- Why did he take the documents?

- Why was he keeping them?

- What did he plan to do with them?

The firehose. Instead, Trump has posted a series of excuses. Most of them contradict each other, and all of them have fallen apart quickly. Anderson Cooper summed them up.

- Trump had been cooperating with DoJ, so there was no excuse to send in a search team. (Reality: Trump’s “cooperative” lawyer had lied to DoJ when it served the subpoena in June.)

- There were no classified documents at Mar-a-Lago.

- The FBI may have planted the classified documents.

- The documents existed and weren’t planted, but Trump had magically declassified them (via a “standing order” that no one in his administration had ever heard of). [1]

- Obama did the same thing. (NARA immediately contradicted this: “The National Archives and Records Administration assumed exclusive legal and physical custody of Obama Presidential records when President Barack Obama left office in 2017, in accordance with the Presidential Records Act.”)

- Taking the classified documents was an honest mistake. Up until the last minute, Trump thought that he could stay in power in spite of losing the election, so when it turned out that the United States was still a democracy after all, he had to pack up the White House quickly. (But why has he kept the documents, and why did his lawyers lie about them?)

- Trump did take the classified documents and keep them after NARA asked for them, but it’s not illegal because he didn’t destroy them or sell them. (Cooper quotes the part of the Espionage Act that says it is illegal.)

Chris Hayes put together a similar list, with videos of Trump’s Fox News puppets making the claims.

There is a name for this propaganda technique: the firehose of falsehood, pioneered by Vladimir Putin. Steve Bannon refers to it as “flooding the zone with shit“.

Cooper refers to the last excuse on his list (put forward by Rudy Giuliani) as the “perfect phone call” phase of the scandal. The reference is to the call that led to Trump’s first impeachment, when he tried to make aid to Ukraine dependent on President Zelenskyy agreeing to a bogus investigation of Joe Biden. Trump and his people had offered a similar firehose of contradictory explanations and distractions, until Trump eventually settled on the defense that he did exactly what he was accused of — and had been denying — but it wasn’t wrong; it was a “perfect phone call“. His later attempt to strong-arm Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger into “finding” enough votes for Trump to win Georgia was also a “perfect phone call“.

This time, though, we’ve seen one step beyond the perfect phone call: The claim that DoJ should back down (even though Trump did commit crimes) for fear of Trump’s violent followers. Thursday, Trump lawyer Alina Habba went on Newsmax to issue an implied threat to the FBI agents who carried out the Mar-a-Lago search. Commenting on the proposal that Trump release the security-camera footage of the search, she said “I would love that.” When shown a video of former FBI counter-intelligence chief Peter Strozk worrying about violence against the agents if their names and faces are identified, Habba seemed fine with that possibility.

Listen. FBI undercover agents, that’s one thing. But when you go into a president’s home, an ex-president’s home, what do you expect is going to happen? What do you expect?

I expect that there are more people out there like the guy who attacked the FBI office in Cincinnati. Habba (and Trump) know that, but they either don’t care or they’re counting on it.

Republicans against law enforcement. Every step of the way, Republican leaders have backed Trump in whichever argument he was making at the time.

Before he knew anything about the search other than that it had happened, Kevin McCarthy, who hopes to be Speaker if Republicans take the House in November, tweeted “I’ve seen enough”. Based on nothing, he immediately adopted Trump’s anti-law-enforcement rhetoric about DoJ’s “intolerable state of weaponized politicization”. He threatened an investigation of DoJ that will “leave no stone unturned”.

Also knowing nothing, and not taking a moment to find out, House Republican Conference Chair Elise Stefanik called the search “a dark day in American history” and called for “an immediate investigation and accountability into Joe Biden and his administration’s weaponizing this department against their political opponents”.

Senator Rand Paul raised the planted-documents theory on Fox News — again, based on nothing. He also called for repealing the Espionage Act that Trump appears to have violated. Numerous Republicans, including Marjorie Taylor Greene, want to defund the FBI. “I mean, we have to,” says Bo Hines, a Trump-endorsed candidate for Congress in North Carolina.

Other than a handful of exiles like Liz Cheney, no major GOP figure is asking Trump to explain why he broke the law.

As we head toward the fall elections, it’s important not to lose sight of what the two parties represent. Democrats are trying to prove that the American system of government still works, by passing laws that address the problems Americans face today, as well as the looming crises of the future. Republicans are a personality cult drumming up fear and paranoia in order to return their leader to power, no matter what he has said or done or might do in the future.

[1] As someone who once had a Top Secret clearance, I can’t let this point go without further comment. A Trump spokesman announced on Hannity:

As we can all relate to, everyone ends up having to bring home their work from time to time. American presidents are no different. President Trump, in order to prepare for work on the next day, often took documents, including classified documents, to the residence. He had a standing order that documents removed from the Oval Office and taken to the residence were deemed to be declassified the moment he removed them.

This is nonsense on many levels. First, if you work with classified documents you don’t take your work home. Ever. If classified documents are signed out to you, you have a safe in your office, and the documents are supposed to be inside the safe when you leave for the evening.

Second, the “standing order” makes no sense. You can only take it seriously if you grossly misconceive what classification means.

What is classified is information, not paper. Suppose there are ten copies of some classified report, and Trump takes one of them home. Does that mean that the report is declassified? If I have one of the other nine copies, can I sell it to the Chinese now? Does it get reclassified in the morning when Trump brings it back? Will my espionage trial hinge on what time it was when I delivered the report to our enemies?

In short, it’s not just that Trump’s “standing order” didn’t exist (as two of his chiefs of staff have verified). It couldn’t exist. By claiming that it did exist, Trump is trying to take advantage of your ignorance. You should feel insulted.

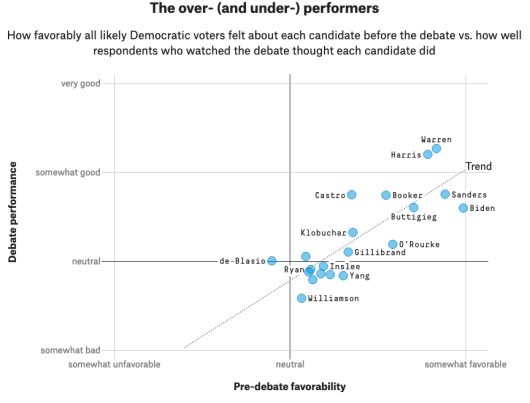

If socialism means buying things collectively through the government, then your local fire department is socialist, and so are the national parks and the interstate highways. Who doesn’t like them? On the other hand, if socialism means buying everything collectively, so that we eat in big government cafeterias rather than in our own kitchens and dining rooms, that would be a lot less popular. So which is it?

If socialism means buying things collectively through the government, then your local fire department is socialist, and so are the national parks and the interstate highways. Who doesn’t like them? On the other hand, if socialism means buying everything collectively, so that we eat in big government cafeterias rather than in our own kitchens and dining rooms, that would be a lot less popular. So which is it?