Is Congress still a branch of government?

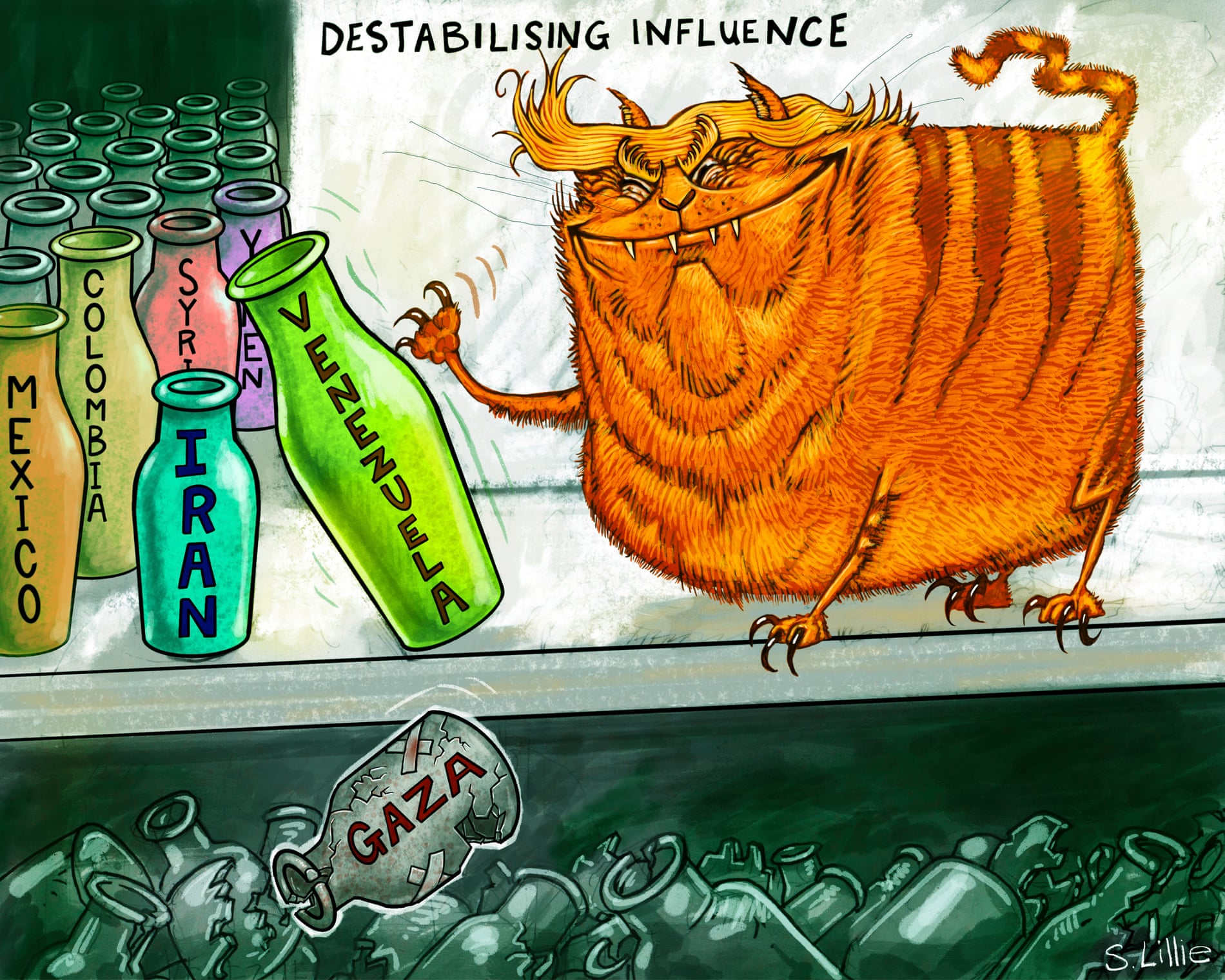

As I often point out: A one-person weekly blog is a bad place to cover breaking news. This morning, the attack on Venezuela is in that nebulous zone between breaking news and an ongoing story: US forces attacked Caracas early Saturday morning, seized President Nicolás Maduro, and apparently left. We can see the general outline of what happened, but what it all means and where it’s all going is still very cloudy.

At the same time, we can’t just wait for the dust to settle, because this is an emergency moment not just for Venezuela, but for America.

For almost a year now, Trump has been pushing Congress into irrelevancy, and the Republican majorities in both houses and in the Supreme Court have been letting him do it: Congress no longer controls government spending. Agencies set up by Congress to be independent of the President have been taken over. The deadlines laid out in the Epstein Files Transparency Act have been ignored. The Education Department established by Congress has been all but eliminated.

And now, Congress has been shoved out of any role in making decisions of war and peace.

Apologists for the administration will tell you that this is nothing new. Ever since World War II (the last war officially declared by Congress), Congress’ constitutional power to declare war has been in tension with the President’s constitutional power as commander in chief. [1] Exactly where the boundary lies — what the President can do on his own and what requires congressional authorization — has been a topic of legitimate debate. A rule of thumb has been that decisions that need to be made quickly belong to the President, while longer commitments require Congress.

Congress asserted its power in the War Powers Act of 1973, which set clear limits on presidential discretion. Subsequent presidents have refused to recognize the constitutionality of the WPA, but have generally respected its boundaries as a matter of good form and sound politics. [2] So, for example, President Bush II sought congressional approval before invading both Iraq and Afghanistan. Lesser military actions have sometimes been initiated without Congress.

But the Venezuela attack is completely outside the bounds of previous constitutional debates. Not only did Trump not seek authorization from Congress, but the congressional “Gang of 8” — leaders of both parties in both houses, who by law are required to be kept informed — did not know about the attack until it was underway. Worse, briefings by Marco Rubio and Pete Hegseth actively misinformed congresspeople about the administration’s intentions. [3] In short, Trump has given Congress no role whatsoever in this decision to go to war.

If Congress were taking seriously its constitutional obligation to preserve our system of checks and balances, it would immediately launch an impeachment. But unfortunately, Republicans in Congress are mostly taking an all’s-well-that-ends-well view: Maduro was bad and he is out now. The mission itself was a stunning display of tactical brilliance. So we should all just be happy with our military success.

The problem with that view is that nothing has ended yet. Immediately, power has not passed to the opposition leaders whose election victory Maduro stole. Instead, Maduro’s vice president Delcy Rodríguez has taken charge of a governing structure that is very much intact. So far, she has sent signals in both directions, denouncing the US attack as “an atrocity that violates international law”, but also saying she want the US government to “collaborate with us on an agenda of cooperation”.

Trump, meanwhile, has said several times that the US is going to “run” Venezuela now and “fix” it. No one in the administration seems to know exactly what that means, or whether American troops will have to occupy the country and take casualties. He seems to imagine that he can manage Rodriguez with threats. But even if he can, will Rodriguez’ people let her stay in power as an American puppet?

Rep. Jim Hines, the ranking Democrat on the House Intelligence Committee (which makes him one of the uninformed Gang of 8) summed up pretty well:

We’re in the euphoria period of acknowledging across the board that Maduro was a bad guy and that our military is absolutely incredible. This is exactly the euphoria we felt in 2002 when our military took down the Taliban in Afghanistan, in 2003 when our military took out Saddam Hussein, and in 2011 when we helped remove Muammar Gaddafi from power in Libya. … Let’s let my Republican colleagues enjoy their day of euphoria, but they’re going to wake up tomorrow morning, knowing, oh my God, there is no plan here any more than there was in Afghanistan, Iraq, or in Libya.

[1] This is one of many situations where the Founders lived in a different world than we do now. The early United States had only a minuscule standing army. So any president who wanted to go to war first had to convince Congress to raise and supply a larger force. But World War II made the US a global superpower, so recent presidents have always had large military forces to command.

[2] One of the lessons of Vietnam was that it’s hard to sustain a war without popular support. Getting Congress to buy in is usually part of a larger effort to sell a war to the general public.

[3] Senator Chris Murphy (D-CT) told CNN’s “State of the Union” yesterday:

I can certainly tell you that the message that [Rubio and Hegseth] sent was that this wasn’t about regime change. When they came to Congress — and they literally lied to our face — they said, “This is just a counternarcotics operation. This is about trying to interrupt the drug flow to the United States.” Right around that same time, the White House Chief of Staff [Susie Wiles] said publicly if we ever had boots on the ground in Venezuela, of course, we would have to come to Congress.