Saturday night, the United States joined Israel’s air war against Iran. The most significant piece of the US intervention was to do what Israel could not: drop giant bunker-buster bombs on the underground Iranian nuclear research facility at Fordow. The US dropped 14 GBU-57 bombs, the largest non-nuclear bomb in our arsenal. (They are also sometimes referred to as MOPs, massive ordinance penetrators.)

The attack came a week after Israel began bombing Iran, and ended several days of what had appeared to be indecision on Trump’s part. Wednesday, he said: “I may do it, I may not do it. I mean, nobody knows what I’m going to do.” He suggested a two-week window for negotiations, then attacked in two days. (As several people have pointed out, “two weeks” is Trumpspeak for “I have no idea”. He seems to believe that two weeks is long enough for the news cycle to forget about an issue.) Like so many of Trump’s actions, this has been justified after the fact as intentional misdirection rather than indecision.

In response, the Iranian Parliament has authorized closing the Strait of Hormuz, but has left the final decision up to Iran’s Supreme National Security Council. One-fifth of the world’s oil goes through that strait, which sits at the mouth of the Persian Gulf. Closing it would raise world oil prices substantially, at least in the short term. So far, markets seem not to be taking the threat seriously.

As I’ve often said, a one-person weekly blog can’t do a good job of covering breaking news, particularly if it breaks on the other side of the world. So you should look to other sources for minute-to-minute or day-to-day coverage.

I also frequently warn about the pointlessness of most news-channel speculation. The vast majority of pundits have no idea what’s going to happen next, so taking their scenarios seriously is at best a waste of time and at worst a way to make yourself crazy.

So if I can’t reliably tell you what’s happening or what’s going to happen, what can I do? At the moment, I think the most useful discussion to have on this blog is to ask the right questions.

What are we trying to accomplish in this war? Failure to get this right has been the major failing in America’s recent wars. Our government has frequently marshaled public support by invoking a wide variety of motives, with the result that we never quite know when we’re done. Our involvement in Afghanistan started out as a hunt for Osama bin Laden and the Al Qaeda leadership behind 9-11. But it quickly evolved into an attempt to establish a friendly regime in Kabul, combat Muslim extremism in general, test counter-insurgency theories, and prove that liberal democracy could work in the Muslim world. So our apparent early success turned into a two-decade failure.

Similarly in Iraq. Were we trying to depose Saddam Hussein? Chase down the (apparently false) rumors of his nuclear program? Control Iraq’s oil? Try yet again to build liberal democracy in the Muslim world? If all we had wanted to do was replace Saddam with a friendlier dictator, that’s not a very inspiring ambition, but we might have been in-and-out quickly. Instead, the failure to find Saddam’s mythical weapons of mass destruction left the Bush administration grasping after some other definition of victory, and getting stuck in another long-term war with dubious goals.

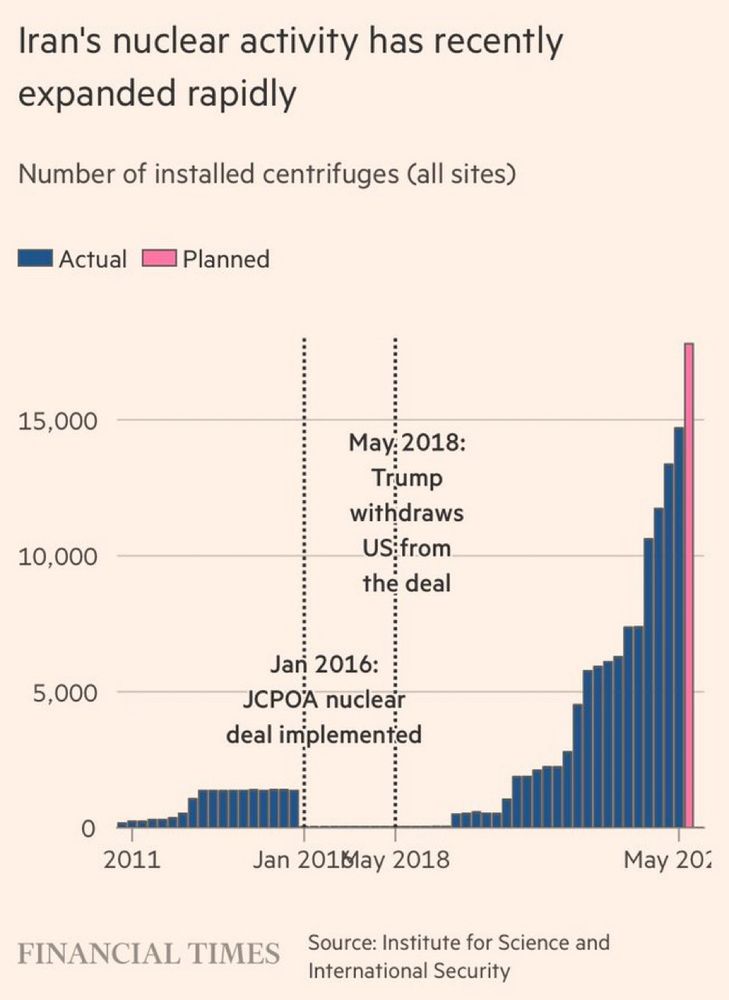

The early indications about this war are not encouraging. Maybe we’re just trying to make sure Iran doesn’t get nuclear weapons. Of course, Obama had a treaty in place that did just that, which Trump ditched, claiming he could get a “better deal”. This war, apparently, is that “better” deal.

But maybe we want to topple the Islamic Republic. Maybe we once again want to control the oil. Those kind of goals bring back Colin Powell’s “Pottery Barn rule“: If we break the country’s government, we own own the ensuing problems until we can fix them. That implies the same kind of long-term commitment we had in Iraq.

Of course, Trump might walk away from such a moral obligation, since he has little notion of morality in any sphere. Then we wind up with a failed state three times the size of Afghanistan, and who knows what kind of mischief might germinate there?

Did our attack work? The answer to this question depends on the answer to the previous question: What does “work” mean?

If the goal was simply to destroy Iran’s current nuclear program, maybe it did work, or can be made to work soon. Trump announced that the attacks were “a spectacular military success” which “completely and totally obliterated” the target sites. But then, he would say that no matter what happened, wouldn’t he? Without someone on the ground, it’s impossible to know.

And without regime change, or without some kind of verifiable agreement in which the current regime renounces nuclear weapons, any such damage is just temporary. Any nation with sufficient money and will can develop nuclear weapons. If Iran comes out of this war with money and will, it can start over.

If the goal is regime change or “unconditional surrender”, the attack hasn’t worked yet and may never. Air war is a poor tool for establishing a new government. I would hope we learned our lesson from Dick Cheney’s famous “we will, in fact, be greeted as liberators” comment, but maybe not. I’ve heard commentators cite internal political opposition to the Iranian theocracy as some kind of ally, but It’s hard for me to picture how that works.

Apply the same logic to the United States: I am deeply opposed to the Trump administration and regard it as a threat to the tradition of American constitutional government. But would I favor some Chinese operation to overthrow Trump? No. What if the internal opposition in Iran is like me? Might they have to unite behind their government to avoid foreign domination?

What could Iran do in response? It’s always tempting to imagine that I will take some extreme action and that will be the end of the matter. Probably you’ve seen this yourself in online discussions. Somebody says something stupid, and you come up with some devastating comment, figuring that the other person will slink off in disgrace.

It doesn’t usually work out that way, does it? The other person will strike back at least as hard as you did, and the exchange might go on for days. You never planned on a flame war eating up hours of your time, but there you are.

Same thing here. Iran might close the Strait of Hormuz to oil tankers, sending the price of gas shooting up and the world economy reeling. It might attack American troops stationed in various places around the Middle East. It might launch terrorist attacks in the US itself. (Do you trust this 22-year-old to protect you?)

Even worse is the possibility of the unexpected. We seem to be at a hinge point in the history of warfare, where drones and various other new technologies change the battlefield in ways that are hard to imagine. Ukraine’s attack on Russia’s Siberian bomber bases is a case in point, but there are others.

Traditional symbols of power may be vulnerable, the way that the American battleships at Pearl Harbor were vulnerable to the new technology of air power. Are we prepared for, say, a massive drone attack sinking an aircraft carrier? What about a cyberattack blacking out some major city? If we suffer such an unexpected blow to our prestige and power, will we be able to respond in a rational way?

What will this war do to the United States itself? The War on Terror undermined the consensus against torture, and authorized previously unprecedented levels of government spying on ordinary Americans.

So far, this war looks like another few steps down the road to autocracy. We attacked Iran because Trump decided to. Bush’s invasion of Iraq, by contrast, was authorized by a bipartisan vote in Congress (to the shame of opportunistic Democrats who should have stood against it). That vote was preceded by a spirited public debate and mass protests.

This time, Congress was not consulted in any formal way. And even informally, a few congressional Republicans were informed ahead of time, but played no part in the decision. Democrats were not consulted at all. No effort at all has been made to convince the American public that this war is in our interests.

So far we’ve been treating this war as if it were a reality show involving Trump, Netanyahu, and the Iranian leadership. We’re just spectators. Until, that is, our city blacks out or we can’t afford gas.