Tuesday was traumatic. How do we recover, as individuals and as a country?

There’s a lot for all of us to process here. About the outside world, the emotions roiling around inside, what we need to be preparing for, and so on. This post is a very quick and incomplete response.

One important thing I’ll say up front: This is a secure-your-own-mask-first situation. We’ve all been knocked off balance, and we need to get our balance back before we go charging out into the world. So do what you need to do and don’t feel guilty about it: gather friends around you, sit in a dark room alone, make art, play solitaire, binge on some silly TV show, whatever. Things are happening deep down, and we need to let those processes do their work. Whatever you decide to do next will benefit if you take care of yourself now.

Me. The hardest thing for me right now is re-envisioning my country. It’s been many years since I have seen America as a “city upon a hill” or the “last best hope of Earth“. But still, I’ve gone on believing that the great majority of Americans aspire to be better and do better. A lot of my commitment to writing has come from my belief that if I work to understand things and explain them clearly, then other people will understand those things too, and most of them will do the right thing, or at least do better than they otherwise would have.

This election demonstrates how naive that belief is. Some Americans were fooled by Trump’s lies about the economy or crime or history or whatever, but many weren’t. They saw exactly what Trump is, and they chose him. Many of the people who believed him weren’t fooled into doing it. They chose to believe, because his lies justified something they wanted to do.

Oddly, though, I am continuing to write, as you can see.

I am reminded of a Zen story: A man meditated in a cave for twenty years, believing that if he could achieve enlightenment, he would rise to a higher state of being and attain mystical powers. One day a great teacher passed through a nearby village, so the man left his cave to seek the sage’s advice. “I wish you had asked me sooner,” the great teacher said sadly, “because there is no higher state of being. There are no mystical powers.”

Crestfallen, the man sat down in the dust and remained there for some while after the sage had continued on his way. As the sun went down, he got up and went back to his cave. Not knowing what else to do with himself, he began his evening meditations. And then he became enlightened.

So far, no enlightenment. But I’ll let you know.

Something similar happens in Elie Wiesel’s recounting of a trial of God he witnessed as a boy in a Nazi concentration camp. (I haven’t recently read either his account or the play it inspired, so I might not have the story exactly right.) After a lengthy and spirited argument, this makeshift Jewish court finds God guilty of violating his covenant and forsaking the Jewish people. And then they move on to their evening prayers.

Election night. Despite everything I’ve said in this blog about avoiding speculation and being prepared for whatever happens, by Election Day I had become fairly optimistic. That all went south very quickly.

I had made myself a list of early indicators, beginning with how Trump Media stock performed that day. (It was way up, a bad sign.) Next came how easily Trump carried Florida. (It was called almost immediately, another bad sign.) Things just got worse from there. I briefly held out some hope for the Blue Wall states (Wisconsin, Michigan, Pennsylvania) until early reports showed Harris underperforming Biden’s 2020 results (when Biden just barely won those states). So I was in bed by 11 and never got up in the night to see if some amazing comeback had started.

I had expected to be deeply depressed if Harris lost, but in fact I haven’t been. I’m disappointed, but I’ve been oddly serene.

No doubt part of my serenity is ignoble. Due to a variety of privileges — I’m White, male, heterosexual, cis, English-speaking, native-born, Christian enough to fake it, and financially secure — I am not in MAGA’s direct line of fire. So whatever trouble I get into will probably come from risks I choose to take rather than brownshirts pounding on my door. Many people are not in my situation, and I am not going to tell them they should be serene.

But there’s also another factor — I hope a larger factor — in how I feel, and I had to search my quote file until I found something that expressed it. In Cry, the Beloved Country Alan Paton wrote:

Sorrow is better than fear. Fear is a journey, a terrible journey, but sorrow is at least an arrival. When the storm threatens, a man is afraid for his house. But when the house is destroyed, there is something to do. About a storm he can do nothing, but he can rebuild a house.

It’s not a perfect metaphor, because we could in fact vote or contribute or volunteer to influence the election. But the scale of the election dwarfed individual action. The closer it got, the more it seemed like a storm. In spite of my propensity to latch onto hopeful signs, in the days and months leading up to the election, I was filled with a very painful dread.

That dread is gone. The hammer has fallen. My faith in the American people was misplaced, so I can now get on with reconstructing that important piece of my worldview.

What happened. As always, we should start with the undeniable facts before making a case for this or that interpretation.

Trump won. He carried the Electoral College 312-226, and also won the popular vote by around 3 1/2 million votes, which is not quite the margin that Obama had over Romney (5 million), and well below the margin Biden had over Trump (7 million) or Obama had over McCain (9 1/2 million).

So it was not a historic landslide, but it was a clear win. Trump had appeared to be ready to try to steal the election if he didn’t win it, but that turned out not to be necessary. Coincidentally, all online talk of “voter fraud” evaporated as it became clear Trump was winning legitimately. The whole point of the GOP’s “election integrity” issue was to provide an excuse not to certify a Harris victory. But with Trump winning, fraud was no longer a concern.

Republicans also won the Senate. Ted Cruz and Rick Scott retained their seats, and no seats flipped from Republicans to Democrats. Democrats lost Joe Manchin’s West Virginia seat, something everyone expected as soon as Manchin announced he wouldn’t run. In addition, Democratic incumbents Sherrod Brown in Ohio, Bob Casey in Pennsylvania, and Jon Tester in Montana were defeated. The new Senate looks to have a 53-47 Republican majority. (Casey is still holding out hope that uncounted provisional ballots will overcome McCormick’s lead. But few think that’s likely.)

The final result in the House is taking longer to emerge, but Republicans look likely to retain their majority there as well.

How did it happen? At the simplest level, it happened because too many people voted for Trump and not enough for Harris. Because the US has secret ballots, there’s no way to know for sure who those people were. But we do have exit polls.

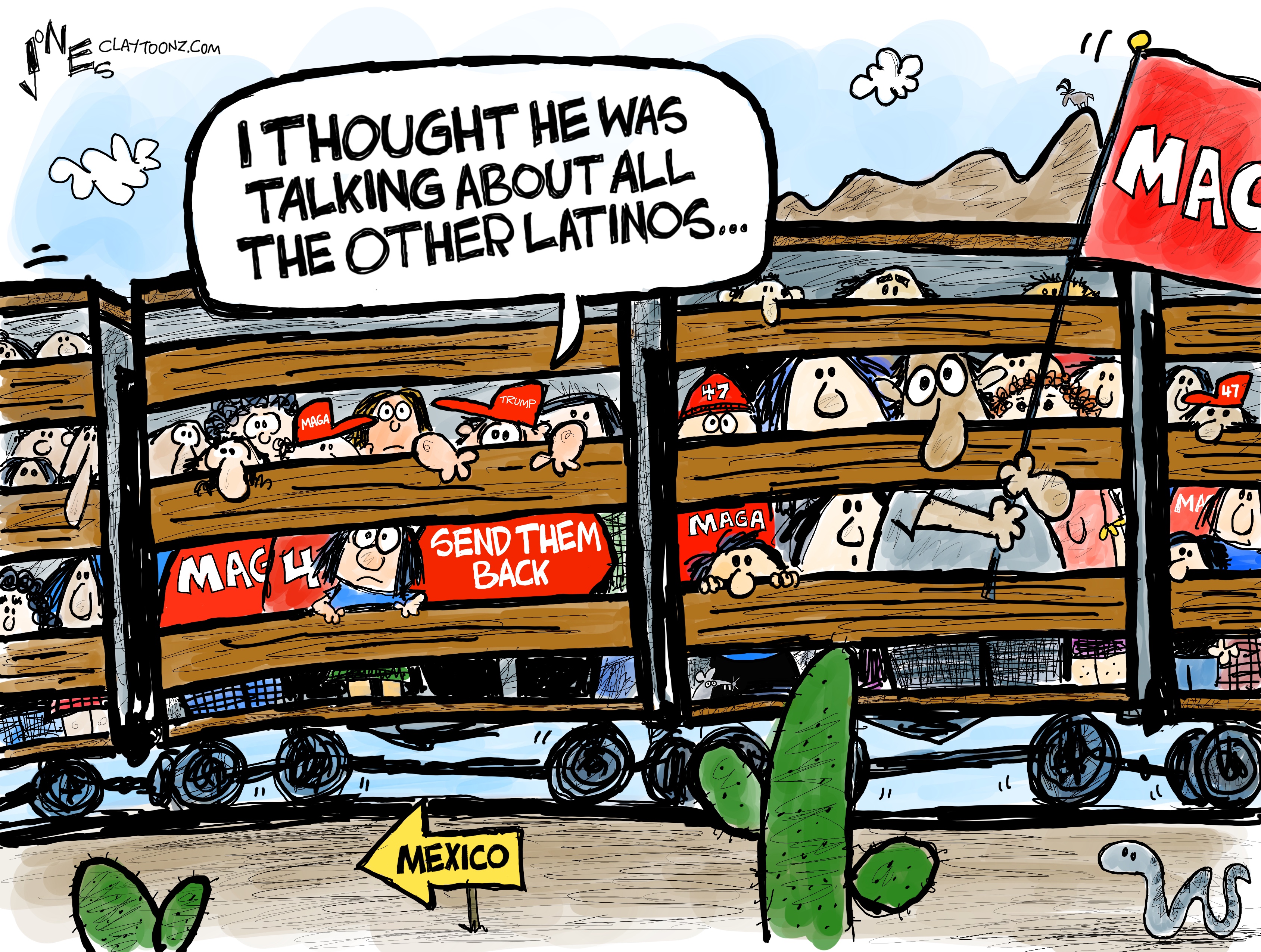

It’s important to phrase things correctly here, because it’s way too easy to scapegoat groups of people unfairly. For example, you’ll hear that Trump won because of the Latino vote (which is true in a sense that we’ll get in a minute). But if you look at the news-consortium exit poll, Harris won the Hispanic/Latino vote 52%-46%, while Trump won the White Evangelical/Born-Again vote 82%-17%. So if you’re looking for someone to blame, look at Evangelicals, not Latinos.

However, most analysts are using the 2020 election as a baseline: Harris lost because she didn’t do as well as Biden did in 2020. And that brings a second exit poll into the conversation. Biden won the Hispanic/Latino vote 65%-32% in 2020, and lost the White Evangelical/Born-Again vote 24%-76%. So if you’re looking for Democratic slippage from 2020 to 2024, you’ll find it in both groups, but the Hispanic/Latino vote stands out; the Democratic margin among Latinos dropped from 33% to 6%.

The Latino vote also stands out because it’s puzzling, at least to non-Latinos like me. Trump ran largely on hostility to non-White immigrants and a promise to deport millions of people, many of whom are Latino. Again, it’s important to nuance this correctly: Latino voters are citizens — non-citizen voting was one of Trump’s lies — and Trump’s prospective deportees are not. Many Latino voters are solidly middle class, speak English with an accent that is more regional than foreign-born, and are well along the immigrant path traveled in the 20th century by Italians and Greeks. It shouldn’t be surprising, then, that as Latinos assimilate into America, they begin to vote more and more like other Americans. After all, Polish Americans may still value their Polish heritage, but they typically don’t base their votes on an agenda of Polish issues.

Still, I have a hard time believing that MAGA racism will respect legal, social, or economic boundaries. Puerto Ricans have been citizens since 1917, and they are still fair game for racist insults. Native Americans are sometimes told to “Go back where you came from”, which is probably Siberia many thousands of years ago. When the racial profiling starts, your skin color and family name may matter more than your legal status. Also, I would suspect that Latino citizens are much more likely than Anglos to know somebody at risk of deportation. I don’t understand why that wasn’t a bigger consideration.

The other example of surprising slippage is women. Biden won the female vote 57%-42%, and Harris won it 53%-45%. This, in spite of not just Harris’ gender, but Trump’s responsibility for the Dobbs decision, a jury affirming that he sexually assaulted E. Jean Carroll, and a series of creepy anti-woman statements.

There was also slippage — not much, but some — among Blacks. Biden won the Black vote 87%-12%, while Harris won it 85%-13%. Harris actually improved slightly on Biden’s performance among Black women (91% to 90%), but did worse among Black men (77% to 79%). (I assume that round-off errors account for the math anomaly in those numbers.)

Meanwhile, the White vote barely changed: Harris and Biden each got 41%.

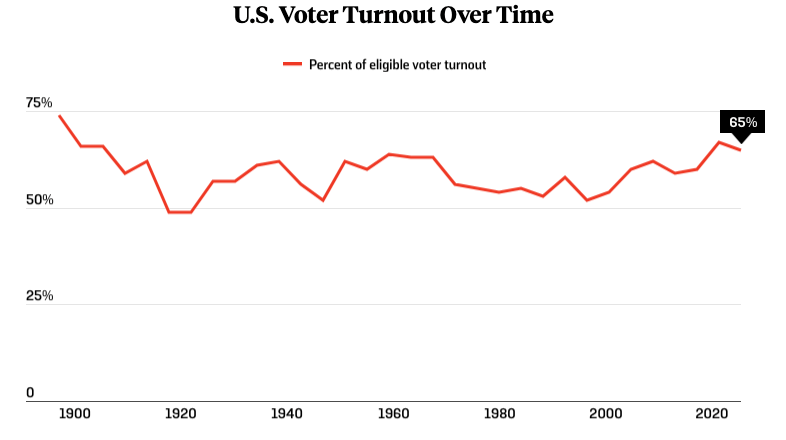

Finally, there’s turnout. Total voter turnout was 65% in 2024 compared to 67% in 2020. However, by American historical standards 65% is high, not low. You have to go back to 1908 (66%) to find another election with turnout this high. The 2020 adjustments to the Covid pandemic made it easier to vote then than at any other time in US history. So it’s unfair to fault the Harris campaign for not matching that turnout.

Why did it happen? I want to urge caution here. After any political disaster, you’ll hear a bunch of voices saying basically the same thing: “This proves I was right all along” or “This wouldn’t have happened if only people had listened to me.”

So Bernie Sanders thinks this election proved Democrats need a more progressive agenda to win back the working class. Joe Manchin says Democrats ignored “the power of the middle”, which implies the party should move right, not left. Others blame the liberal cultural agenda — trans rights, Latinx-like language, defund the police — for turning off working-class voters. Or maybe Harris’ outreach to Nikki Haley conservatives wasn’t convincing enough, and the problem was all the progressive positions she espoused in her 2020 campaign. Josh Barro suggests the problem is that blue states and cities are not being governed well.

The gap between Democrats’ promise of better living through better government and their failure to actually deliver better government has been a national political problem. So when Republicans made a pitch for change from all this (or even burn-it-all-down), it didn’t fall flat.

Basically, whatever you believe, you can find somebody telling you that you are right, and Harris would have won if she had done what you wanted.

I want to encourage you to resist that message — and I’m going to try to resist it myself — because none of us will learn anything if we just insist we’ve been right from Day 1. We should all bear in mind that the US is a very big, very diverse country, and (whoever you are) most voters are not like you. It’s easy for me to imagine positions or messages or candidates that would have made me more enthusiastic about voting Democratic. But we need to be looking for an approach that inspires a broader coalition than showed up for Harris last week. That coalition is going to have to include people you don’t understand, the way I don’t understand the Latinos who voted for mass deportation, the women who voted to give away their own rights, or the young people who voted to make climate change worse.

This is exactly the wrong time for I-was-right-all-along thinking. Back in 1973, Eric Hoffer wrote:

In a time of drastic change it is the learners who inherit the future. The learned usually find themselves equipped to live in a world that no longer exists.

So much of what passes for “obvious” or “common sense” right now only sounds that way because it is well grounded in a worldview that no longer applies. This is a truth that is easy to see in other people, but hard to see in ourselves.

We’re going to be in a weird position for the foreseeable future: Trump is going to try to run over a lot of legal, cultural, and political boundaries, and we need to be prepared to resist. It would be great to be able to resist from a place of rock-solid certainty. But if we’re going to turn this around in the long term, we also need to be humble and flexible in our thinking. Fairly often, we’re going to have to think thoughts like: “I don’t really don’t understand a lot of what’s happening, but I’m pretty sure I need to put my body here.”

Explanations we can eliminate. You don’t have to have the right explanation to recognize wrong ones.

Harris ran a bad campaign. Josh Marshall puts his finger on the statistic that debunks this.

In the seven swing states, the swing to Trump from 2020 to 2024 was 3.1 percentage points. In the other 43 states and Washington, DC the swing was 6.7 points.

Both candidates focused their ads, their messaging, and their personal appearances on the swing states. If the Trump campaign had been running rings around the Harris campaign, this arrow would have pointed in the other direction. In short: If you were a 2020 Biden voter, the more you saw of Harris and Trump, the more likely you were to vote for Harris.

I live in a typically liberal Boston suburb. Massachusetts is about as far from a swing state as you can get, so no national figures ever showed up here. Occasionally we’d see some ads aimed at New Hampshire, but we didn’t get nearly the blitz that Pennsylvanians got. And guess what? Harris slipped behind Biden’s performance here too.

Harris should have picked Josh Shapiro as her VP. This would be a good argument if Harris had won the national popular vote, but failed in the Electoral College because she lost Pennsylvania. But she also lost Wisconsin, where Walz probably helped her.

Also, Harris won the Jewish vote by a wide margin: 78%-22%. So Shapiro’s Judaism probably wouldn’t have helped the ticket.

Harris should have moved further left. We can never say what would have happened if a candidate had delivered a completely different message from the beginning. But I think it’s pretty clear that simply shifting left down the stretch, i.e., emphasizing the more liberal parts of Harris’ message and record, wouldn’t have helped.

The best evidence here comes from comparing Harris to Democratic Senate candidates. Candidates who are perceived as more liberal, like Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, generally did slightly worse than Harris in their states, while candidates perceived as more conservative (Tim Kaine and Bob Casey, say) did somewhat better.

I’m ignoring a bunch of the Senate races because I don’t see much to be gleaned from them. Jon Tester ran to Harris’ right in Montana and did 7% better, but Harris was never going to be conservative enough to win Montana — and as it turned out, Tester wasn’t either. Maryland’s Angela Alsobrooks ran almost 8% behind Harris (and won anyway), but that’s more a reflection on her opponent, former governor Larry Hogan, one of the few non-MAGA Republican candidates. (It suggests that a moderate Republican could have won a landslide on the scale of Nixon in 1972 or LBJ in 1964.)

If you saw much election advertising, you know that Republicans worked hard to paint Harris as part of the “radical left”. I don’t think they’d have done that if they thought moving left would help her.

Things I think I know. I don’t have a sweeping theory, but I’ll offer a few tentative pieces of a theory.

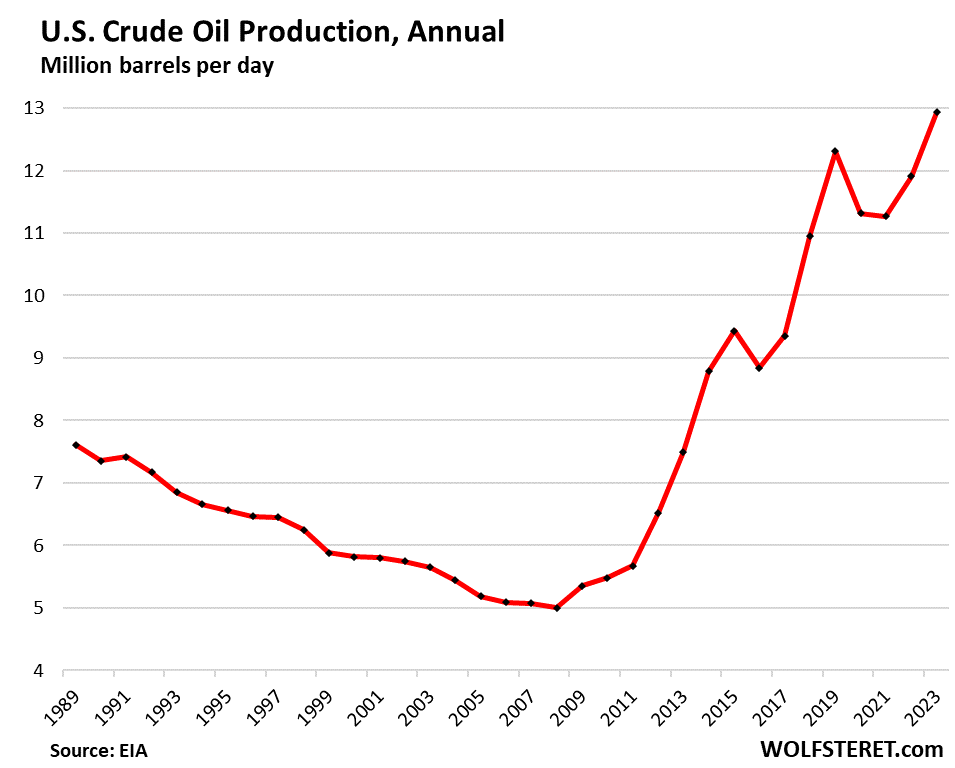

We lost the information war. The aspect of this campaign I found most personally frustrating was how much of the pro-Trump argument centered on things that simply aren’t true. Our cities are not hellholes. There is no migrant crime wave. Crime in general is not rising. Most of the countries that compete with us would love to have our economy. Inflation is just about beaten. America was far from “great” when Trump left office in 2021. Trump has no magic plan for peace in Ukraine and Gaza. The justice system has favored Trump, not persecuted him.

Jess Piper writes:

I hate to say this, but it’s true: Ignorance won. And it will keep winning until we realize that we can’t win by playing politics as usual. This isn’t the same world. Knocking 100 doors is a personal connection that might win a small race — I don’t know that it can change the larger races. Trump’s folks weren’t knocking doors. They were lying to the masses through an extreme right-wing reality that most of us can’t conceive.

And Michael Tomasky elaborates:

This is the year in which it became obvious that the right-wing media has more power than the mainstream media. It’s not just that it’s bigger. It’s that it speaks with one voice, and that voice says Democrats and liberals are treasonous elitists who hate you, and Republicans and conservatives love God and country and are your last line of defense against your son coming home from school your daughter. And that is why Donald Trump won.

It’s hard to know how important the pervasive misperception of facts really was. Did people believe Trump’s nonsense because it was actually convincing? Or did they want to support Trump for some other reason and latched onto whatever pro-Trump “facts” they could find? (Birtherism was like that. People who didn’t want to admit that a Black president scared or angered them instead claimed to be convinced that Obama was born in Kenya, despite clear evidence to the contrary.)

Past presidential campaigns have included some misinformation, but they revolved much more around philosophical disagreements not easily reduced to facts, like the significance of the national debt, or how to balance the public and private sectors.

One of the big questions going forward is whether Democrats want to continue being the reality-based party. I hope we do, just for the sake of my conscience. But if so, how do we make that work in the current information environment?

Harris had a steep hill to climb. Around the world, countries went through a period of inflation as their economies reopened after the pandemic. And around the world, the governments in power got thrown out. Here’s how Matt Yglesias put it just before the election:

The presumption is that Kamala Harris is — or at least might be — blowing it, either by being too liberal or too centrist, too welcoming of the Liz Cheneys of the world or not welcoming enough or that there is something fundamentally off-kilter about the American electorate or American society.

Consider, though, that on Oct. 27, Japan’s long-ruling conservative Liberal Democratic Party suffered one of its worst electoral results. In late September, Austria’s center-right People’s Party saw an 11-percentage-point decline in vote share and lost 20 of its 71 seats in Parliament. Over the summer, after being in power for 14 years, Britain’s Conservative Party collapsed in a landslide defeat, and France’s ruling centrist alliance lost over a third of its parliamentary seats.

… It is not a left-right thing. Examples show that each country has unique circumstances. Center-left governments from Sweden to Finland to New Zealand have lost, but so have center-right governments in Australia and Belgium. This year the center-left governing coalition in Portugal got tossed out. Last year the People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy, the incumbent center-right governing party in the Netherlands, finished third in an election dominated by far-right parties.

Not long after Yglesias wrote that, Germany’s governing coalition collapsed.

I’m reluctant to give this explanation too much credit, because it says this election was a one-off and there’s nothing really to learn, other than to avoid being in power at the end of a pandemic. So in that sense it’s too easy. But it’s also a real thing that is an important part of the picture.

Harris’ outreach to Republican women came up empty. I’m not going to say it was a bad idea, but it didn’t work. I haven’t seen an exit poll that specifically breaks out Republican women, but the overall slippage among women in general makes it unlikely that many Liz Cheney Republicans crossed over.

After Trump’s 2016 win, big-city journalists trying to figure out Trump voters made countless trips to small-town diners. This time, I’d like to see them hang out in upscale suburban coffee shops and talk to women in business suits. Why did so many of them stay loyal to their party’s anti-woman candidate?

Democrats need a utopian vision. If Democrats had complete control and could remake America however we wanted, what would that look like? I honestly don’t know.

It’s not like Democrats don’t stand for anything. I can list a bunch of things an unconstrained Democratic administration would do, like make sure everyone gets the health care they need, raise taxes on billionaires, ban assault weapons, cut fossil fuel emissions, and make states out of D. C. and Puerto Rico. Maybe it would also reform the food system and break up the tech monopolies, though the details on those two are fuzzy.

But a list of policies doesn’t add up to a vision.

Whatever you think of it, libertarianism provided pre-MAGA conservatives with a utopian vision for decades. Republicans didn’t usually run on an explicitly libertarian platform, but libertarian rhetoric and libertarian philosophy was always in the background. (Reagan in his first inaugural address: “Government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem.”) Trump mostly turned away from that, and slogans like “America First” and “Make America Great Again” may be vague, but they also evoke something sweeping.

I can’t think of anything comparable on the left. The communist vision collapsed with the Soviet Union, and I don’t know anybody who wants to revive it. But in the absence of a political vision, we’re left with a technocracy: Do what the experts think will work best.

This is a problem a new face won’t solve. Gavin Newsom or Gretchen Whitmer or even AOC is not a vision.

What happens next? It’s Trump’s move. We don’t know yet who he’s going to appoint to high office or what the agenda of the new Congress will be. Establishing authoritarian government is work, and he may not have the energy for it. Maybe he’ll get so distracted by seeking his revenge against individuals that he won’t get around to systematically destroying democracy. We’ll see.

I’m reminded of a story Ursula le Guin told decades ago, repeating something from another woman’s novel: A female character discovers her baby eating a manuscript.

The damage was not, in fact, as great as it appeared at first sight to be, for babies, though persistent, are not thorough.

Trump has many babyish traits. We can hope that he won’t be thorough enough to do as much damage as we now fear.

This Adam Gurri article is full of good advice, but I especially appreciate this:

The biggest weakness of The Women’s March was its lack of strategic objective or timing. It simply demonstrated mass dissatisfaction with the Trump administration the day after it began. The best use of mass protest is in response to something specific. It does not even need to be an action, it can be as simple as some specific thing that Trump or a member of his administration says. But it has to have some substance, some specific area of concern. Perhaps it is about prosecuting his enemies. Perhaps it is about mass deportations. No one doubts there will be a steady supply of choices to latch onto. Those seeking to mobilize protests need to make sure they do pick something specific to latch onto, and be disciplined in making opposition to it the loudest rhetoric of the protest.

This time around, I don’t expect protesting against Trump himself to get very far. His followers expect it; they will just roll their eyes and talk about “Trump Derangement Syndrome”. But protesting something Trump does will at least draw attention to that thing. We have to wait for him to do something objectionable. Unfortunately, it probably won’t be a long wait.

In the meantime, prepare. Take care of yourself. Regain your balance.